Abstract

This paper studies the impact of the Brazilian Arranjos Productivos Locais (APL) policy, a cluster development policy, on small and medium enterprises’ (SMEs) performance. Using firm-level data on SMEs for the years 2002–2009, this paper combines fixed effects with reweighting methods to estimate both the direct and the indirect causal effects of participating in the APL policy on employment growth, value of total exports, and likelihood of exporting. Our results show that APL policy generates a positive direct impact on the three outcomes of interest. They also show evidence of short-term negative spillovers effects on employment in the first year after the policy implementation and positive spillovers on export outcomes in the medium and long term. Thus, our findings highlight the importance of accounting for the timing and gestation periods of the effects on firm performances when assessing the impact of clusters policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Because of Marshall’s seminal work, this phenomenon is often referred to as Marshallian externalities. In more generic terms, the literature has also referred to the concept of industry-specific local externalities (ISLE). Henderson et al. (1995) refer to these types of industry-specific externalities that arise from regional agglomeration as “localization externalities”, in particular, when firms operate in related sectors and are closely located.

Given the confidentiality of the data, the estimations were conducted following the Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada’s (IPEA) microdata policy, which implies working in situ under the supervision of its staff and with blinded access to sensible information.

The simplest definition of an industry cluster is derived from the work of Porter (1990), who defines clusters as “a geographic concentration of competing and cooperating companies, suppliers, service providers, and associated institutions”.

Recent studies present evidence of the effect of clustering on the growth of new technology-based firms (Maine et al. 2010), the survival and performance of new firms (Wemberg and Lindqvist 2010), and how firm growth is influenced by the strength of the industrial cluster in which the firm is located (Beaudry and Swann 2009).

For a review on coordination problems in development, see Hoff (2000). On clusters and coordination failures, see also Rodriguez-Clare (2005).

As Anderson et al. (2004) pointed out, thorough evaluations of specific cluster initiatives and cluster actions are in fact few and have been developed only in few countries. Few solid attempts have been made to assess whether first-best results are obtained, go beyond efficiency in use of given resources to encompass economic results, or take into account interactions and synergies in the performance of different actors. Further, most evaluations of cluster policies pursued still focus on single tools, which fits poorly with the systemic notion of cluster policy.

The ICP was initiated by the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry in 2001 and aimed at developing regional industries and included both direct R&D support and indirect networking/coordination support.

The econometric analysis presented in Maffioli (2005) confirms a strong correlation between PROFO firms’ innovativeness and industrial cooperation, proving the existence of an interactive learning process among participant firms. Using sociometric data to refine the analysis of the impact of the program on the network multiplier results show that participant firms increase their productivity and that this improvement is strongly correlated with firm centrality and network density, which are the two variables best representing the structure and function of the network multiplier and that are affected by PROFO.

As defined in the Termo de Referencia para Politica Nacional de Apoio ao Desenvolvimiento de arranjos productivos locais (2004).

SEBRAE’s budget comes from contributions of 0.3–0.6 % of Brazilian corporations’ payrolls. Resources are collected by the Brazilian Social Security Institute (INSS) and transferred to SEBRAE.

See Clerides et al. (1998), Bernard and Jensen (1999), Aw et al. (2000), Bernard et al. (2003) and Bernard and Jensen (2004). Furthermore, Melitz (2003)’s model showed how the exposure to trade induces only the more productive firms to export while simultaneously forcing the least productive firms to exit reallocating market shares (and profits) toward the more productive firms and contributing to an aggregate productivity increase.

The cost of entering into new markets often consists of knowledge related to the assessment of the market demand, product standards, distribution channels, regulatory environment etc. (Melitz 2003).

On the role that public policy can play in fostering coordination among exporters see also Bernard and Jensen (2004).

For instance, firms that share the geographical location with participating firms may indirectly benefit from higher foreign direct investment in the region attracted by cluster firms (De Propris and Driffield 2006). Bronzini and Piselli (2009) consider geographical spillovers assuming that factors enhancing productivity in one region can also affect the productivity in the neighboring regions. Bottazzi and Peri (2003) use geographical proximity as a channel for R&D spillovers.

Similar to the firm identifier, the municipality identifier was re-codified by IPEA to preserve the confidentiality of the data. Thus, it is not possible to link the APL (or firms) to real municipalities.

We will refer to an industry with a positive number of treated firms within a municipality as a “treated industry-municipality” and to the municipalities with absence of treated firms as “non-treated municipalities”.

See Bertrand et al. (2004) for a formal discussion on differences-in-differences estimates.

A similar approach is followed by Moretti (2004) to measure human capital spillovers in manufacturing in the US.

The Herfindahl index was created by industry-municipality-year using level of employment. For a full discussion on measures of concentration see Hay and Morris (1987).

The RAIS is an annual survey including socio-economic information of firms in Brazil. It is an administrative record of the labor force profile which is mandatory in Brazil for all firms in all sectors.

Using the reweighting method will only keep firms who were observed in both pre-treatment years, i.e. 2002–2003.

Several industries presented only one observation in the 2007 RAIS and were therefore excluded due to confidentiality issues. Other industries such as paper products, metal products, medical instruments and chemical products industries were also excluded since they had a negligible number of APL participating firms.

Both for employment and for total exports, the series will be expressed in natural logarithms. For the outcome log of exports we assign the value of 0 when firms have 0 exports to avoid excluding non-exporting firms from the sample, which could bias the results by affecting the composition of the treatment and control groups (see Angrist and Pischke, 2008).

The large direct effect on exports could be partially due to the fact that we are not excluding non-exporting firms and therefore the average of exports before the program was implemented is relatively low (U$S 21,744) compared with the one that only considers exporting firms (US$ 914,738).

Since the assessment of heterogeneous effects inevitably implies statistical power problems—i.e. the sub-sample of beneficiaries for each interaction term could be rather small—we follow the standard rule-of-thumb of considering interactions for which at least twenty beneficiaries are available. We make an exception in the case of the heterogeneity by size, because the sample can only be divided in small and medium firms.

\( Cs_{i } \_2002 \) is omitted in Eq. (2) because of perfect collinearity.

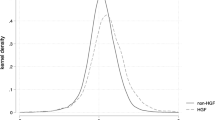

Additional evidence of the validity of this assumption is also provided by the graphs and tables in appendix 1 and 2, which show that treated and the reweighted comparison groups are very similar both in levels and trends of observed characteristics in the pre-treatment period.

References

Anderson, T., Hansson, E., Schwaag, S., & Sörvik, J. (2004). The cluster policies white book. Malmo: Iked.

Angrist, J., & Pischke, J.-S. (2008). Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Aranguren, M. J., Larrea, M., & Navarro, I. (2006). The policy process: Clusters versus spatial networks in the Basque country. In C. Pitelis, R. Sugden, & J. R. Wilson (Eds.), Clusters and globalization (pp. 258–280). Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Arráiz, I., Henriquez, F., & Stucchi, R. (2013). Supplier development programs and firm performance: Evidence from Chile. Small Business Economics, 41(1), 277–293.

Arráiz, I., Melendez, M., & Stucchi, R. (2014). Partial credit guarantees and firm performance: Evidence from Colombia. Small Business Economics. doi:10.1007/s11187-014-9558-4.

Arrow, K. J. (1962). The economic implications of learning by doing. Review of Economic Studies, 29(3), 155–173.

Aw, B. Y., Chung, S., & Roberts, M. J. (2000). Productivity and turnover in the export market: Micro-level evidence from the Republic of Korea and Taiwan (China). World Bank Economic Review, 14(1), 65–90.

Beaudry, C., & Peter Swann, G. M. (2009). Firm growth in industrial clusters of the United Kingdom. Small Business Economics, 32(4), 409–424.

Benavente, J., Crespi, G., Figal Garone, L., & Maffioli, A. (2012). The impact of national research funds: A regression discontinuity approach to the Chilean FONDECYT. Research Policy, 41(8), 1461–1475.

Bernard, A. B., Eaton, J., Jensen, J. B., & Kortum, S. (2003). Plants and productivity in international trade. American Economic Review, 93(4), 1268–1290.

Bernard, A. B., & Jensen, J. B. (1999). Exceptional exporter performance: Cause, effect, or both? Journal of International Economics, 47(1), 1–25.

Bernard, A. B., & Jensen, J. B. (2004). Why some firms export?. Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(4), 561–569.

Bertrand, M., Duflo, E., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). How much should we trust difference-in-differences estimates? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1), 249–275.

Blundell, R., & Costas Dias, M. (2000). Evaluation methods for non-experimental data. Fiscal Studies, 21(4), 427–468.

Boekholt, P. (2003). Evaluation of regional innovation policies in Europe. In P. Shapira & S. Kuhlmann (Eds.), Learning from science and technology policy evaluation: Experiences from the United States and Europe (pp. 244–259). Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Bottazzi, L., & Peri, G. (2003). Innovation and spillovers in regions: Evidence from European patent data. European Economic Review, 47(4), 687–710.

Bronzini, R., & Piselli, P. (2009). Determinants of long-run regional productivity with geographical spillovers: The role of R&D, human capital and public infrastructure. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 39(2), 187–199.

Buendia, F. (2005). Towards a system dynamic-based theory of industrial clusters. In C. Karlsson, B. Johansson, & R. R. Stough (Eds.), Industrial clusters and inter-firm networks (pp. 83–106). Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Campos, R. Stallivieri, F., Vargas, M., Mato, M., (2010). politicas estaduais para arranjos produtivos locais no sul, sudeste e centro-oeste do Brasil. E-papers Servicos Editoriais Ltda., Rio de Janeiro. http://www.bndes.gov.br/SiteBNDES/export/sites/default/bndes_pt/Galerias/Arquivos/empresa/pesquisa/Consolidacao_APLs_Sul_Sudeste.pdf

Cassiolato, J. E. (2012) Nota técnica síntese implementacao e avaliacao de politicas para arranjos produtivos locais: Proposta de modelo analitico e classificatório. Ministerio de Desenvolvimento, Indústria e Comércio Exterior. http://portalapl.ibict.br/export/sites/apl/galerias/biblioteca/Nota_Txcnica_6_VF.pdf

Cassiolato, J. E., Lastres, H., & Maciel, M. L. (2003). Systems of innovation and development: Evidence from Brazil. Cheltenham, RU: Edward Elgar.

Castillo, V., Maffioli, A., Rojo, S., & Stucchi, R. (2014). The effect of innovation policy on SMEs’ employment and wages in Argentina. Small Business Economics, 42(2), 387–406.

Cheshire, P. C. (2003). Territorial competition: Lessons for (innovation) policy. In J. Brocker, D. Dohse, & R. Soltwedel (Eds.), Innovation clusters and interregional competition (pp. 331–346). Berlin: Springer.

Ciccone, A., & Hall, R. (1996). Productivity and the density of economic activity. American Economic Review, 86(1), 54–70.

Clerides, S., Lack, S., & Tybout, J. R. (1998). Is learning by exporting important? Micro-dynamic evidence from Colombia, Mexico and Morocco. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113(3), 903–947.

Combes, P., Duranton, G., & Gobillon, L. (2008). Spatial wage disparities: Sorting matters. Journal of Urban Economics, 63(2), 723–742.

Combes, P., Duranton, G., Gobillon, L., & Roux, S. (2010). Estimating agglomeration economies with history, geology, and worker effects. In E. L. Glaeser (Ed.), Agglomeration Economics (pp. 15–66). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Crespi, G., Maffioli A., Melendez, M. (2011). Public support to innovation: The Colombian Colciencias’ experience. Technical Notes No. IDB-TN-264, Science and Technology Division, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, DC. http://www.iadb.org/wmsfiles/products/publications/documents/35940030.pdf

De Propris, L., & Driffield, N. (2006). The importance of clusters for spillovers from foreign direct investment and technology sourcing. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 30(2), 277–291.

Dehejia, R., & Wahba, S. (1999). Causal effects in nonexperimental studies: Reevaluating the evaluation of training programs. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 94(448), 1053–1062.

DTI. (2004). A practical guide to cluster development: A report to the Department of Trade and Industry and the English RDAs. London: DTI.

Dumais, G., Ellison, G., & Glaeser, E. (2002). Geographic concentration as a dynamic process. Review of Economics and Statistics, 84(2), 193–204.

Ellison, G., & Glaeser, E. (1997). Geographic concentration in U.S. manufacturing industries: A dartboard approach. Journal of Political Economy, 105(5), 889–927.

Ellison, G., & Glaeser, E. (1999). The geographic concentration of industry: Does natural advantage explain agglomeration? American Economic Review, 89(2), 311–316.

Ellison, G., Glaeser, E., & Kerr, W. (2010). What causes industry agglomeration? Evidence from coagglomeration patterns. American Economic Review, 100(3), 1195–1213.

European Commission. (2002). Regional clusters in Europe. Observatory of European SMEs 2002/3, Brussels: EC.

Falk, O., Heblich, S., & Kipar, S. (2010). Industrial innovation: Direct evidence from a cluster-oriented policy. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 40(6), 574–582.

Feser, E. (2002). The relevance of clusters for innovation policy in Latin America and the Caribbean. Background paper prepared for the World Bank, LAC Group. http://www.urban.uiuc.edu/faculty/feser/Pubs/Relevance%20of%20clusters.pdf

Galiani, S., Gertler, P., & Schargrodsky, E. (2005). Water for life: The impact of the privatization of water services on child mortality. Journal of Political Economy, 113(1), 83–119.

Giuliani, E., Maffioli, A., Pachecho, M. Pietrobelli, C., Stucchi, R. (2013). Evaluating the impact of cluster development programs. Technical Note No. IDB-TN-551, Competitiveness and Innovation Division, Institutions for Development, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, DC. http://www.iadb.org/wmsfiles/products/publications/documents/37925857.pdf

Giuliani, E., Pietrobelli, C., & Rabellotti, R. (2005). Upgrading in global value chains: Lessons from Latin American clusters. World Development, 33(4), 549–573.

González, M., Maffioli, A., Salazar, L., Winters, P. (2010). Assessing the effectiveness of agricultural interventions. Special Topic, Development Effectiveness Overview, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, DC. http://publications.iadb.org/bitstream/handle/11319/1240/Assessing%20the%20Effectiveness%20of%20Agricultural%20Interventions.pdf?sequence=1

GTZ. (2007). Cluster management: A practical guide. Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH: Eschborn.

Hainmueller, J. (2012). Entropy balancing for causal effects: A multivariate reweighting method to produce balanced samples in observational studies. Political Analysis, 20(1), 25–46.

Hainmueller, J., & Xu, Y. (2011). Ebalance: A Stata package for entropy balancing. Journal of Statistical Software, 54(7), 1–18.

Hall, B., & Maffioli, A. (2008). Evaluating the impact of technology development funds in emerging economies: Evidence from Latin America. European Journal of Development Research, 20(2), 172–198.

Hanson, G. (2001). Scale economies and the geographic concentration of industry. Journal of Economic Geography, 1(3), 255–276.

Hartmann, C. (2002). Styria. In P. Raines (Ed.), Cluster development and policy (pp. 123–140). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Hay, D., & Morris, D. (1987). Industrial economics, theory and evidence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heckman, J., & Hotz, V. (1989). Choosing among alternative non-experimental methods for estimating the impact of social programs: The case of Manpower training. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 84(408), 862–874.

Heckman, J., Ichimura, H., Smith, J., & Todd, P. (1998). Characterizing selection bias using experimental data. Econometrica, 66(5), 1017–1098.

Heckman, J., Ichimura, H., & Todd, P. (1997). Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator: Evidence from evaluating a job training program. Review of Economic Studies, 64(4), 605–654.

Henderson, V., Kunkoro, A., & Turner, M. (1995). Industrial development of cities. Journal of Political Economy, 103(5), 1067–1090.

Hoffman, W. (2004). A contribuição da Inteligência Competitiva para o Desenvolvimento de Arranjos Produtivos Locais: Caso Jaú-SP. Revista Eletrônica Biblioteconomia, Florianópolis. http://www.pg.utfpr.edu.br/dirppg/ppgep/dissertacoes/arquivos/4/Dissertacao.pdf

Holland, P. (1986). Statistics and causal inference. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 81(396), 945–960.

Imbens, G., Rubin, D., & Sacerdote, B. (2001). Estimating the effect of unearned income on labor earnings, savings, and consumption: Evidence from a survey of lottery players. The American Economic Review, 91(4), 778–794.

Jaffe, A., Trajtenberg, M., & Henderson, R. (1993). Geographic localization of knowledge spillovers as evidenced by patents citations. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(3), 577–598.

Krugman, P. (1991). Geography and trade. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kullback, S. (1959). Information theory and statistics. New York: Wiley.

La Rovere, R., Hasenclever, L., & Erber, F. (2004). Industrial and technology policy for regional development: Promoting clusters in Brazil. The International Journal of Technology Management and Sustainable Development, 2(3), 205–217.

La Rovere, R., & Shibata, L. (2007). Politicas de apoio a micro e pequenas empresas e desenvolvimento local: alguns pontos de reflexao. Revista REDES, 11(3), 9–24.

Lastres, H., Cassiolato, J. (2003). Glossario de arranjos e sistemas produtivos e inovativos locais. Rede de pesquisa em sistemas produtivos e inovativos locais, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. http://mdic.gov.br/portalmdic/arquivos/dwnl_1289323549.pdf

Lastres, H., & Cassiolato, J. (2005). Innovation systems and local productive arrangements: New strategies to promote the generation, acquisition and diffusion of knowledge. Innovation and Economic Development, 7(2), 172–187.

Lastres, H., Cassiolato, J., & Maciel, M. (2003). Systems of innovation for development in the knowledge era: An introduction. In J. E. Cassiolato, H. M. M. Lastres, & M. L. Maciel (Eds.), Systems of innovation and development: Evidence from Brazil (pp. 1–33). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Li, D., Lu, Y., & Wu, M. (2012). Industrial agglomeration and firm size: Evidence from China. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 41(1–2), 135–143.

Litzenberger, T., & Sternberg, R. (2005). Regional clusters and entrepreneurial activities: Empirical evidence from German regions. In C. Karlsson, B. Johansson, & R. R. Stough (Eds.), Industrial clusters and inter-firm networks (pp. 260–302). Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar.

López Acevedo, G., & Tan, H. (2010). Impact evaluation of SME programs in Latin America and the Caribbean. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications.

Machado, S. A. (2003). Dinâmica dos arranjos produtivos locais: Um estudo de caso em Santa Gertrudes, a nova capital da cerâmica brasileira. Tese de Doutorado, Escola Politécnica, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/3/3136/tde-27102003-151054/

Maffioli, A. (2005). The formation of network and public intervention: Theory and evidence from the Chilean experience. ISLA Working Paper 23, Univertità Bocconi. ftp://www.unibocconi.it/pub/RePEc/slp/papers/islawp23.pdf

Maffioli, A., Ubfal, D., Vázquez Baré, G., & Cerdán Infantes, P. (2012). Extension services, product quality and yields: The case of grapes in Argentina. Agricultural Economics, 42(6), 727–734.

Maine, E., Shapiro, D., & Vining, A. (2010). The role of clustering in the growth of new technology-based firms. Small Business Economics, 34(2), 127–146.

Maliranta, M., Mohnen, P., & Rouvinen, P. (2009). Is inter-firm labor mobility a channel of knowledge spillovers? Evidence from a linked employer–employee panel. Industrial and Corporate Change, 18(6), 1161–1191.

Marshall, A. (1920). The principles of economics. New York: Macmillan.

Martin, P., Mayer, T., & Mayneris, F. (2011). Public support to clusters: A firm level study of French ‘Local Productive Systems’. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 41(2), 108–123.

Melitz, M. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725.

Moretti, E. (2004). Workers’ education, spillovers, and productivity: Evidence from plant-level production functions. American Economic Review, 94(3), 656–690.

Mytelka, L., & Farinelli, F. (2005). De aglomerados locais a sistemas de inovacao. In H. Lastres, J. E. Cassiolato, & A. Arroio (Eds.), Conhecimento, sistemas de inovacao e desenvolvimento. Rio de Janeiro: Editora UFRJ/Contraponto.

Nishimura, J., & Okamuro, H. (2011). R&D productivity and the organization of cluster policy: An empirical evaluation of the Industrial Cluster Project in Japan. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 36(2), 117–144.

Politica de Apoio ao Desenvolvimiento de Arranjos Productivos Locais. (2004). Termo de Referencia para Politica Nacional de Apoio ao Desenvolvimiento de Arranjos Produtivos Locais. Versao para Discussao do GT Interministerial, Versao Final (16/04/2004), Brasil. http://www.mdic.gov.br/arquivos/dwnl_1289322946.pdf

Porter, M. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations. New York: Free Press.

Porter, M. (1998). Clusters and the new economics of competition. Harvard Business Review, 76(6), 77–91.

Porter, M. (2000). Location, competition, and economic development: Local clusters in a global economy. Economic Development Quarterly, 14(1), 15–34.

Rip, A. (2003). Societal challenges for R&D evaluation. In P. Shapira & S. Kuhlmann (Eds.), Learning from science and technology policy evaluation: Experiences from the United States and Europe (pp. 32–53). Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Rizov, M., Oskam, A., & Walsh, P. (2012). Is there a limit to agglomeration? Evidence from productivity of Dutch firms. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 42(4), 595–606.

Rodriguez-Clare, A. (2005). Coordination failures, clusters and microeconomic interventions. Economía, 6(1), 1–29.

Rodriguez-Clare, A. (2007). Clusters and comparative advantage: Implications for industrial policy. Journal of Development Economics, 82(1), 43–57.

Romer, P. M. (1986). Increasing returns and long-run growth. Journal of Political Economy, 94(5), 1002–1037.

Rosenstein-Rodan, P. (1943). Problems of industrialization of Eastern and South-Eastern Europe. The Economic Journal, 53(210/211), 202–211.

Rosenthal, S., & Strange, W. (2001). The determinants of agglomeration. Journal of Urban Economics, 50(2), 191–229.

Rosenthal, S., & Strange, W. (2003). Geography, industrial organization, and agglomeration. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 85(2), 377–393.

Rosenthal, S., & Strange, W. (2010). Small establishments/big effects: Agglomeration, industrial organization and entrepreneurship. In E. L. Glaeser (Ed.), Agglomeration economics (pp. 277–302). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Santos, F., Crocco, M., Lemos, M. B. (2002a). Arranjos e sistemas produtivos locais em “espaços industriais” periféricos: Estudo comparativo de dois casos brasileiros. Belo Horizonte: UFMG/Cedeplar. http://internotes.fieb.org.br/rede_APL/arquivos/fabianamarcomauro.pdf

Santos, F., Crocco, M., Simoes, R. (2002b). Arranjos productivos locais informais: Uma análise de components principais para Nova Serrana e Ubá—Minas Gerais. Anais do X Seminário sobre a Economia Mineira, Belo Horizonte, Cedeplar, UFMG. http://www.cedeplar.ufmg.br/diamantina2002/textos/D30.PDF

Schmiedeberg, C. (2010). Evaluation of cluster policy: A methodological overview. Evaluation, 16(4), 389–412.

Shefer, D. (1973). Localization economies in SMA’s: A production function analysis. Journal of Regional Science, 13(1), 55–65.

Souza Filho, O. V., & Martins, R. S. (2013). A efetividade da colaboracao entre organizacoes do arranjo produtivo local (APL): Experiencias dos processos logísticos nas industrias do vale da eletronica de Minas Gerais—Brasil. Revista REDES, 18(2), 8–37.

Sveikauskas, L. (1975). The productivity of cities. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 89(3), 393–413.

Volpe, C., & Carballo, J. (2008). Is export promotion effective in developing countries? Firm-level evidence on the intensive and the extensive margins of exports. Journal of International Economics, 76(1), 89–106.

Wemberg, K., & Lindqvist, G. (2010). The effect of clusters on the survival and performance of new firms. Small Business Economics, 34(3), 221–241.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Patrick Franco Alves, Conner Mullaly, and Rodolfo Stucchi for useful discussions and comments on this project. We would also like to thank SEBRAE and two anonymous referees for their suggestions and comments. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Inter-American Development Bank. The usual disclaimer applies. Senior authorship is not assigned.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Figal Garone, L., Maffioli, A., de Negri, J.A. et al. Cluster development policy, SME’s performance, and spillovers: evidence from Brazil. Small Bus Econ 44, 925–948 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9620-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9620-2