Abstract

Research usually finds a positive size-efficiency relationship, but few studies focus on sectors dominated by small and medium-sized firms (SMEs). This paper fills this gap by analyzing this relationship in the German mechanical engineering industry sector, which is both successful and increasingly dominated by SMEs. The analysis, using a large and representative dataset, finds that small and large firms are, on average, the most efficient ones, while medium-sized firms have, on average, the greatest inefficiencies. Thus, the size-efficiency relationship is U-shaped rather than monotonically increasing. Additionally, the analysis finds that companies with active owner(s) are significantly more efficient and that capital firms are less efficient than firms with personally liable owners. Being located in either East or West Germany has no effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Here, these are firms with fewer than 500 employees.

During the financial and economic crisis of the years 2009 and 2010, the German government, in cooperation with state owned and private banks, set up funds in order to increase the equity base of SMEs.

Among them, the small firms with fewer than 50 employees account for 10 % of all jobs and 6 percent of the industry sales in 2004. The larger ones, on the other hand, consist of firms with either 100–249 or 250–500 employees, each accounting for 19 % of sales and for 21 and 18 % of the industry employment (Federal Statistical Office Germany 2005).

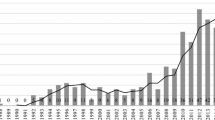

Data taken from the GENESIS database of the German Federal Statistical Office; https://www-genesis.destatis.de.

Nevertheless, he also states that financial constraints still at least partly explain why small, but efficient, firms stay small, at least for some time (Jovanovic 1982).

We forego a repeated presentation here and refer to very good description of the method in Badunenko (2010).

The approach is intuitive and easy to implement, based on the MATLAB code by Simar (2003).

The data are confidential but not exclusive. Researchers can apply for their use. See Zühlke et al. (2004) and http://www.forschungsdatenzentrum.de/en/index.asp.

For more information about the German Cost Structure Census, see Fritsch et al. (2004).

Almost all characteristics entail information in monetary form. This study only uses and sums up the monetary information. The only exception is the number of employees, but this is not used as input an factor in the calculation of efficiency scores.

Here we follow the approach of Simar and Wilson (2005), who use a capital proxy for the analysis of banking size. In the long run, though, the size of a firm cannot be regarded as exogenous. But since the efficiencies are estimated by means of input and output data on yearly frontiers, the assumption that the size of a firm is more or less stable within a year is imposed.

To overcome this problem as much as possible one needs to have a representative dataset (as in this study), one needs to run a decent outlier detection method (as in this study) and one needs to apply the respective bootstrapping method (as in this study). Yet, pure efficiency numbers, derived in other studies by DEA or SFA and with different datasets, cannot be used to judge whether industry A in country A is more efficient than industry A (or B, C, etc.) in country B.

In addition Martin-Marcos and Suarez-Galvez (2000) find an average efficiency for the Spanish engineering industry of 0.64. Moreover, the efficiency shown in Table 2 is biased corrected. Without that correction the mean efficiency would be 0.73 and more than 5 % of the firms have an efficiency score of one.

The P values of the applied bilateral Wilcoxon rank-sum tests are not reported here, but are available upon request from the author.

This follows from the simple curve discussion in which the first differentiation is set equal to zero and solved for size.

Given the results of Table 3, a robustness check with output defining size seems natural. However, no variable used in the first stage of the approach can be applied in the second stage, thus these estimations are not possible.

References

Agell, J. (2004). Why are small firms different? Managers’ views. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 106, 437–452.

Aggrey, N., Eliab, L., & Jospeh, S. (2010). Firm size and technical efficiency in East African manufacturing firms. Current Research Journal of Economic Theory, 2, 69–75.

Audretsch, D. B. (1999). Small firms and efficiency. In Z. J. Acs (Ed.), Are small firms important? Their role and impact (pp. 21–23). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publisher.

Audretsch, D. B. (2002). The dynamic role of small firms: Evidence from the U.S. Small Business Economics, 18, 13–14.

Badunenko, O. (2010). Downsizing in the German chemical manufacturing industry during the 1990s. Why is small beautiful? Small Business Economics, 2010, 413–431.

Banker, R. D. (1993). Maximum likelihood, consistency and data envelopment analysis: A statistical foundation. Management Science, 39, 1265–1273.

Bentzen, J., Madsen, E. S., & Smith, V. (2011). Do firms’ growth rates depend on firm size? Small Business Economics. doi:10.1007/s11187-011-9341-8.

Cazals, C., Florens, J. P., & Simar, L. (2002). Nonparametric frontier estimation: A robust approach. Journal of Econometrics, 106, 1–25.

Charnes, A., Cooper, W. W., & Rhodes, E. (1978). Measuring the inefficiency of decision making units. European Journal of Operational Research, 2, 429–444.

Coase, R. H. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4, 386–405.

Dalton, S., Friesenhahn, E., Spletzer, J., & Talan, D. (2011). Employment growth by size class: firm and establishment data. Monthly Labor Review, 129, 3–12.

Daraio, C., & Simar, L. (2007). Advanced robust and nonparametric methods on efficiency analysis, methods and applications. New York: Springer.

Dhawan, R. (2001). Firm size and productivity differential: theory and evidence from a panel of US firms. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 44, 269–293.

Diaz, M. A, & Sanchez, R. (2008). Firm size and productivity in Spain: A stochastic frontier analysis. Small Business Economics, 30, 315–323.

Farrell, M. J. (1957). The measurement of productive efficiency. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A, 120, 253–281.

Federal Statistical Office Germany. (2005). Fachserie 4/Reihe 4.1.2, Produzierendes Gewerbe Betriebe, Beschäftigte und Umsatz des Verarbeitenden Gewerbes sowie des Bergbaus und der Gewinnung von Steinen und Erden nach Beschäftigtengrößenklassen. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt.

Federal Statistical Office Germany. (2006). Fachserie 4/Reihe 4.3, Produzierendes Gewerbe, Kostenstrukturerhebung des verarbeitenden Gewerbes sowie des Bergbaus und der Gewinnung von Steinen und Erde 2004. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt.

Fritsch, M., Görzig, B., Hennchen, O., & Stephan, A. (2004). Cost structure surveys for Germany. Schmollers Jahrbuch/Journal of Applied Social Science Studies, 124, 557–566.

Funke, M., & Rahn, J. (2002). How efficient is the East German economy? An exploration with microdata. Economics of Transition, 10, 201–223.

Gumbau-Albert, M., & Maudos, J. (2002). The determinants of efficiency: The case of Spanish industry. Journal of Applied Economics, 34, 1941–1948.

Haltiwanger, J., & Krizan, C. J. (1999). Small business and job creation in the United States: The role of new and young businesses. In Z. J. Acs (Ed.), Are small firms important? Their role and impact (pp. 79–97). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Jovanovic, B. (1982). Selection and the evolution of industry. Econometrica, 50, 649–670.

Kneip, A., Park, B. U., & Simar, L. (1998). A note on the convergence of nonparametric DEA estimators for production efficiency scores. Econometric Theory, 14, 783–793.

Kneip, A., Simar, L., & Wilson, P.W. (2008). Asymptotics and consistent bootstraps for DEA estimators in non-parametric frontier models. Econometric Theory, 24, 1663–1697.

Martin-Marcos, A., & Suarez-Galvez, C. (2000). Technical efficiency of Spanish manufacturing firms: a panel data approach. Journal of Applied Economics, 32, 1249–1258.

Shephard, R. W. (1970). Cost and production function. New York: Princeton University Press.

Simar, L., & Wilson P. W. (1998). Sensitivity analysis of efficiency scores: how to bootstrap in nonparametric frontier models. Management Science, 44, 49–61.

Simar, L, & Wilson P. W. (2000). A general methodology for bootstrapping in non-parametric frontier models. Journal of Applied Statistics, 27, 779–802.

Simar, L, & Wilson P. W. (2002). Non-parametric test of return to scale. European Journal of Operational Research, 139, 115–132.

Simar, L. (2003). Detecting outliers in frontier models: A simple approach. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 20, 391–424.

Simar, L, & Wilson P. W. (2007). Estimation and inference in two-stage, semiparametric models of production processes. Journal of Econometrics, 136, 31–64.

Simar, L., & Wilson, P. W. (2005). Statistical inference in nonparametric frontier models: Recent developments and perspectives. In H. Fried, C. A. K. Lovell, & S. S. Schmidt (Eds.), The measurement of productive efficiency techniques and application (pp. 1–125). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tavares, G. (2002). Bibliography of data envelopment analysis (1978–2001). Rutcor Research Report, RRR01-02. Piscataway: Rutgers Center for Operational Research.

Taymaz, E. (2005). Are small firms really less productive? Small Business Economics, 25, 429–445.

Wheelock, D. C., & Wilson, P. W. (2009). Robust non-parametric quantile estimation of efficiency and productivity change in U.S. commercial banking, 1985–2004. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 27, 354–368.

Williamson, O. E. (1967). Hierarchical control and optimum firm size. Journal of Political Economy, 75, 123–138.

Yang, C. H., & Chen, K. H. (2009). Are small firms less efficient? Small Business Economics, 32, 375–395.

Zühlke, S., Zwick, M., Scharnhorst, S., & Wende, T. (2004). The research data centres of the federal statistical office and the statistical offices of the Länder. Schmollers Jahrbuch/Journal of Applied Social Science Studies, 124, 567–578.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the anonymous referees for useful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Appendix Tables 5, 6, 7, 8.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schiersch, A. Firm size and efficiency in the German mechanical engineering industry. Small Bus Econ 40, 335–350 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-012-9438-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-012-9438-8