Abstract

In Russian, argument clauses can be nominalized by the demonstrative pronoun to ‘that’ (henceforth, to čto-clauses). Although to čto-clauses have often been discussed in the literature, their distribution is still not fully understood and is subject to conflicting claims, partly owing to the fact that to čto in the accusative/nominative position coincides with the “emerging” (noninflected) complementizer to čto in nonstandard colloquial varieties of Russian. This paper focuses on the acceptability status of to čto-clauses in the accusative position, which have been deemed generally degraded (or unacceptable) in standard Russian by some accounts (referred to here as case-based accounts), in contrast to the oblique/object-of-P position (where both čto- and to čto-clauses are optional). On other accounts that view to čto as the marker of given/familiar information, there is no general constraint against to čto-clauses in the accusative as long as the predicate is compatible with familiar complements. In this paper, we test these two accounts experimentally, focusing on the prediction of the givenness-based account according to which different predicate classes, specifically presuppositional vs. nonpresuppositional, differ in the frequency of to čto-clauses (irrespective of their case properties). Using elicited production and acceptability judgments, we confirm the view that to čto-clauses in the accusative position with presuppositional predicates, e.g. otricat’ ‘deny’, osoznat’ ‘realize’, etc. are indeed acceptable, in contrast to nonpresuppositional predicates. In addition, we show that presuppositional predicates show a higher rate of to čto-clauses in the oblique/object-of-P position, further supporting the givenness-based account. Yet, we also find that accusative-marked to čto-clauses with predicates like osoznat’ ‘realize’ are produced much less frequently than expected based on their presuppositionality. We explain this by an independent dispreference for accusative-marked to čto-clauses in production, supporting a weaker version of the case-based view. We offer a tentative proposal as to how case and presuppositionality can be combined in a unified account of the distribution of to čto-clauses. Last but not least, our results also shed light on the status of nonstandard to čto, which, as we show, displays a specific acceptability profile characteristic of stigmatized grammatical variants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Whenever possible, we use examples from the Russian National Corpus (RNC, http://ruscopora.org). We use the following abbreviations in the glosses: acc = accusative case, comp = complementizer, dat = dative case, gen = genitive case, inf = infinitive, ins = instrumental case, neg = negation, nom = nominative case, prep = prepositional case, prt = particle.

To ‘that’ can also nominalize subjunctive clauses and embedded question (Hansen et al., 2016).

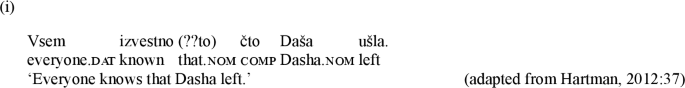

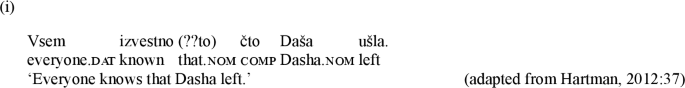

According to Hartman (2012), this generalization subsumes to čto-clauses both in the accusative and in the postverbal nominative position, as in (i), by virtue of both being complements of V. However, we do not share Hartman’s (2012) judgment and align here with works which take to čto-clauses in the postverbal nominative position to be optional (Knyazev, 2016:40; Letuchiy, 2021:294). In this paper, we do not discuss sentential subjects in any detail.

The first part of the generalization, (5-a), is qualified to account for the fact that some accusative-taking verbs also allow PP complements headed by o ‘about’, in which case to čto-clauses (inside PP) are possible. See Sect. 2.1.

The second part of the generalization, (5-b), is not obvious as one may think that it is PPs that are optional, while to čto-clauses are obligatory as they occur in the context of P (Hansen et al., 2016; Artiom Fedorinchik, p.c.). However, we think that that this would miss the similarity between the alternations in (3) and (4), whatever its ultimate source.

For example, in all RNC texts written after 1950 (accessed December 2020; September 2022) we found only 19 examples with to čto-clauses in the accusative position with ponimat’/ponjat’ ‘understand’, 16 with podtverždat’/podtverdit’ ‘confirm’, 10 with dokazyvat’/dokazat’ ‘prove’, 7 with otricat’ ‘deny’ and 7 with osoznavat’/osoznat’ ‘realize’, as compared to, respectively, 8317, 206, 2364, 244 and 487 examples with bare čto-clauses (not manually checked for embedded questions and light-headed relative clauses).

In addition, they are also found with the veridical/optionally factive predicate dokazyvat’ ‘prove’ (see the previous footnote).

There is no established convention for glossing “nonstandard to čto”. We use the most transparent glossing reflecting its relation to to čto-clauses in standard Russian. We also assume that in the context of accusative-assigning verbs to is accusative and is otherwise nominative. Note that nonstandard to čto is usually rendered without a comma in the literature, as opposed to the standard to čto. In this paper, we adopt the convention of not using comma for both types of to čto, to remain neutral as to the analysis of the construction at hand, which is not always self-evident. However, in the experimental materials for Experiment 2 we, instead, used commas between to and čto for both standard and (supposedly) nonstandard constructions, in order to keep to the conventions of Russian punctuation.

In addition, Kobozeva (2013) assumes that to in to čto-clauses can also be a marker of constrastive focus (cf. (2-b)). However, it remains unclear on Kobozeva’s account whether and how the role of contrastive focus and givenness in the licensing of to can be unified.

Kobozeva (2013) does not discuss speech act verbs like govorit’ ‘say’ and utverždat’ ‘claim’ (with accusative complements), but we take her account to also apply to them.

We assume that the strongest version of Kobozeva’s (2013) account, whereby the relevant verbs categorically disallow familiar complements, cannot be maintained, in view of the observation, noted by Zaliznjak (1988) and others, that all nonpresuppositional verbs are in principle compatible with familiar complements in the right kind of context, e.g. under negation or in presuppositional contexts introduced by ‘also’, ‘again’, aspectual predicates, etc. Therefore, selection of new-information complements by the relevant class of predicates must be viewed as a strong default, as opposed to a categorical requirement (cf. the formulation in (11-a)).

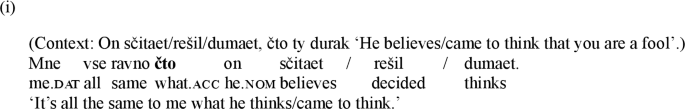

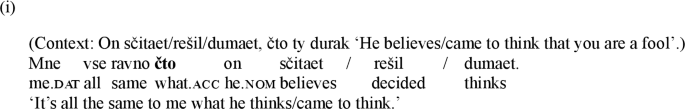

Thus, we classified sčitat’ ‘think’, rešit’ ‘decide’ and dumat’ ‘think’ in (15-a) as accusative-taking, based on the fact that they are compatible with the interrogative/relative pronoun čto ‘what’ in the accusative, as in (i), and despite the fact that they disallow the èto ‘this’-proform in the accusative (Kobozeva, 2013).

The pictures were made using the application Procreate.

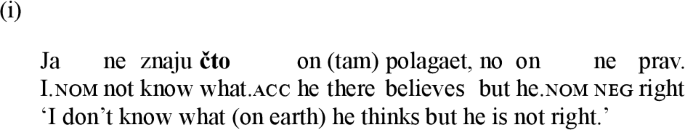

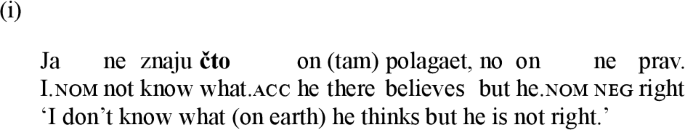

We find examples like (i), with polagat’ ‘suppose’ taking an accusative čto ‘what’ as somewhat marked, but clearly not unacceptable.

Below we report the model with subject, item and by-subject and by-item complement type slopes as random effects. We dropped the by-subject interaction slope because the model with it did not converge within a reasonable time. We also dropped the by-subject verb class slope because it had a variance very close to zero (0.007) and did not improve the model fit (p = 0.95).

Z-score ratings are obtained by dividing the difference between each individual rating and the average rating of the participant by that participant’s standard deviation.

Somewhat unexpectedly, acceptable fillers with čtoby received a rating close to intermediate acceptability. An examination of the mean ratings for the individual sentences (see items 1, 4 and 12 in Appendix A.3) showed that all of them had a rating rather close to the mean (3.28–3.43). Although we do not have an explanation for this fact, we tentatively assume that participants may have found these sentences pragmatically implausible (for whatever reason), which may have resulted in their lowered ratings.

We hypothesize that voobražat’ ‘imagine’ did not show a contrast between all the three complement types because of the specific experimental sentence that we used (see item 11 in Appendix A.2), which may have encouraged participants to construe the verb as a process verb, akin to dumat’ o ‘think about’. This, in turn, may have increased the acceptability of both o tom čto (by analogy with dumat’ o) and to čto (since the process construal should presumably imply a preexisting mental object, leading to some similarity with presuppositional verbs), and simulaneously decreased the acceptability of čto, which normally requires a stative interpretation (Zaliznjak & Mikaèljan, 1988). As for polagat’ ‘suppose’, we do not fully understand why to čto with it received intermediate acceptability. One possibility is that this verb has a rather bookish flavor in modern Russian and is not commonly used except in parentheticals. As a result, speakers may not have clear intuitions about its syntactic behavior.

We do not have an explanation for why o tom čto was rated as having intermediate acceptability with soobrazit’‘figure out’. For voobražat’ ‘imagine’ see the previous footnote.

A reviewer wonders if the contrast between the production and the acceptability data of to čto-clauses with accusative-taking presuppositional predicates may have to do with the relative easiness of reconstructing a constrastive focus context, which also licenses to čto-clauses (cf. (2-b)). Although this is an interesting suggestion, we do not see how this could explain the data. Since all sentences (or sentence frames) in both experiments were presented in out-of-the-blue contexts (except for response-stance predicates in Experiment 1, where this is infelicitous), participants were indeed very unlikely to construe those contexts as contrastive. However, this precisely predicts, incorrectly, that there should be no contrast between the two experiments with presuppositional predicates, as well as between presuppositional vs. nonpresuppositional predicates in Experiment 2.

References

Anand, P., & Hacquard, V. (2014). Factivity, belief and discourse. In L. Crnic & U. Sauerland (Eds.), The art and craft of semantics: a festschrift for Irene Heim (pp. 69–90). Cambridge MA: MITWPL

Anand, P., Grimshaw, J., & Hacquard, V. (2017). Sentence embedding predicates, factivity and subjects. In C. Condoravdi (Ed.), A festschrift for Lauri Karttunen. Retrieved September 22, 2022, from https://arnoldzwicky.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/finalproofs.pdf.

Bochnak, M. R., & Hanink, E. A. (2022). Clausal embedding in Washo: complementation vs. modification. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 40, 979–1022.

Bogal-Allbritten, E., & Moulton, K. (2017). Nominalized clauses and reference to propositional content. The Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung, 21, 215–232.

Bondarenko, T. (2021). How do we explain that CPs have two readings with some verbs of speech? In Proceedings of the 39th West coast conference on formal linguistics. http://tbond.scripts.mit.edu/tb/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Bondarenko_TalkPaper.pdf.

Cattell, R. (1978). The source of interrogative adverbs. Language, 54, 61–77.

Christiansen, M. H., & Chater, N. (2016). Creating language: integrating evolution, acquisition, and processing. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Christensen, R. H. B. (2019). Ordinal-regression models for ordinal data, R package version 2019.12-10. Retrieved September 22, 2022, from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ordinal/ordinal.pdf.

Degen, J., & Tonhauser, J. (2022). Are there factive predicates? An empirical investigation. Language, 98(3), 552–591.

Djärv, K. (2019). Factive and assertive attitude reports. PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania.

Egorova, A. D. (2018). Funkcionirovanie novogo komplementajzera to čto v russkoj sponannoj reči [Functioning of new complementizer to čto in spontaneous Russian speech]. MA thesis, Moscow State University.

Featherston, S. (2005). The decathlon model of empirical syntax. In M. Reis & S. Kepser (Eds.), Linguistic evidence (pp. 187–208). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Glovinskaja, M. Ja. (2000). Aktivnye processy v grammatike (na materiale innovacij i massovyx jazykovyx ošibok) [Active processes in the grammar (on the basis of innovations and widespread language errors)]. In E. A. Zemskaja (Ed.), Russkij jazyk konca XX stoletija (1985—1995) (pp. 237–302). Moscow: Jazyki russkoj kul’tury.

Hansen, B., Letuchiy, A., & Błaszczyk, I. (2016). Complementizers in Slavonic (Russian, Polish, and Bulgarian). Complementizer semantics in European languages (pp. 175–223). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Hartman, J. (2012). Varieties of clausal complementation. PhD diss., MIT.

Kastner, I. (2015). Factivity mirrors interpretation: the selectional requirements of presuppositional verbs. Lingua, 164, 156–188.

Khomitsevich, O. (2008). Dependencies across phases: from sequence of tense to restrictions on movement. PhD diss., Utrecht University.

Knyazev, M. (2016). Licensing clausal complements. The case of Russian čto-clauses. PhD diss., Utrecht University.

Knyazev, M. (2022). Spanning complement-taking verbs and spanning complementizers: on the realization of presuppositional clauses. Journal of Linguistics, 58(4), 887–899. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022226722000160.

Kobozeva, I. M. (2013). Uslovija upotreblenija «to» pered pridatočnym iz’’jasnitel’nym s sojuzom «čto» [Conditions for the use of “to” before explicative clauses with the subordinate conjunction “chto”]. In O. Inkova (Ed.), Du mot au texte. Études slavo-romanes (pp. 129–148). Bern: Peter Lang.

Korotaev, N. A. (2013). Polipredikativnye konstrukcii s to čto v nepubličnoj ustnoj reči. [Polypredicative constructions with to čto in non-public spoken Russian]. In Komp’juternaya lingvistika i intellektual’nye texnologii: Po materialam ežegodnoj Meždunarodnoi konferencii «Dialog» (pp. 324–331). Moscow: Russian State University for the Humanities.

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B., & Christensen, R. H. B. (2017). lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software, 82, 1–26.

Letuchiy, А. (2021). Russkij jazyk o situacijax. Konstrukcii s sentencial’nymi aktantami v russkom jazyke. Saint Petersburg: Аletejya.

Letuchiy, А. (2022). Argumentnaja struktura mental’nyx predikatov v russkom jazyke: vzaimodejstvie semantičeskix, sintaksičeskix i kommunikativnyx faktorov. In S. Koeva, E. Ivanova, J. Tiševa, & A. Zimmerling (Eds.), Ontologija na situaciite za s’’stojanie – lingvistično modelirane. S’’postavitelno izsledvane za b’’lgarski i ruski (pp. 210–246). Sofia: Izdatelstvo na BAN Prof. Marin Drinov.

Patel-Grosz, P., & Grosz, P. G. (2017). Revisiting pronominal typology. Linguistic Inquiry, 48(2), 259–297.

Pesetsky, D. (1997). Optimality theory and syntax: movement and pronunciation. In D. Archangeli & D. T. Langendoen (Eds.), Optimality theory. An overview (pp. 134–170). Oxford: Blackwell Sci.

Prince, E. F. (1992). The ZPG letter: subjects, definiteness, and information-status. In W. C. Mann & S. A. Thompson (Eds.), Discourse description: diverse linguistic analyses of a fund-raising text (pp. 295–325). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Šatunovskiij, I. B. (1988). Èpistemičeskie glagoly: kommunikativnaja perspektiva, prezumpcii, pragmatika [Epistemic verbs: communicative perspective, presuppositions, pragmatics]. In Logičeskij analiz jazyka. Znanie i mnenie (pp. 18–22). Moscow: Nauka.

Serdobol’skaja, N. V., & Egorova, A. D. (2019). Morfosintaksičeskie svojstva nenormativnyx konstrukcij s to čto v russkoj razgovornoj reči [Morphosyntax of non-standard constructions with to čto in Colloquial Russian]. Voprosy Jazykoznanija, 5, 41–72.

Simonenko, A., & Voznesenskaia, A. (2019). An emerging veridical complementizer to chto in Russian. In M. Bağrıaçık, A. Breitbarth, & K. De Clercq (Eds.), Mapping linguistic data. Essays in honor of Liliane Haegeman (pp. 262–268). Retrieved September 22, 2022, from https://www.haegeman.ugent.be/.

Simons, M. (2007). Observations on embedding verbs, evidentiality, and presupposition. Lingua, 117, 1034–1056.

Sorace, A., & Keller, F. (2005). Gradience in linguistic data. Lingua, 115, 1497–1524.

Stepanov, A. (2001). Cyclic domains in syntactic theory. PhD diss., University of Connecticut.

Švedova, N. J. (Ed.) (1982). Russkaja grammatika. Moscow: Nauka.

Vogel, R. (2019). Grammatical taboos. Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft, 38(1), 37–79.

Zaliznjak, A. A. (1988). O ponjatii implikativnogo typa (dlja glagolov s propozicionalnym aktantom) [On the notion of implicative type (for verbs with propositional arguments)]. In Logičeskij analiz jazyka. Znanie i mnenie (pp. 107–121). Moscow: Nauka.

Zaliznjak, A. A., & Mikaèljan, I. L. (1988). Ob odnom sposobe razrešenija neodnoznačnosti v glagolax propozicional’noj ustanovki [On the one type of ambiguity resolution with propositional attitude predicates]. In Semiotičeskie aspekty formalizacii intellektualʹnoĭ dejatelʹnosti. Škola-seminar “Boržomi-88” (pp. 303–306). Moscow: Tezisy dokladov.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Experimental materials

1.1 A.1 Experiment 1. Experimental sentences

-

(1)

— Ты вчера поддавался на соревнованиях.

— Нет, я не поддавался.

Вася отрицает ____.

-

(2)

— Мне сегодня никто не звонил.

Петя подтвердил ____.

-

(3)

— Есть столько прекрасных вещей в мире!

Аня осознала ____.

-

(4)

— Вообще-то я был прав в этом споре.

Саша доказал ____.

-

(5)

— Не придавай этому значения.

— Маша, твои слова не были пустым звуком

Вася знает ____.

-

(6)

— Лена завтра отмечает день рождения.

Петя помнит ____.

-

(7)

— Наверное, мои друзья уже смотрели этот фильм.

Саша предполагает ____.

-

(8)

— У моего поступка есть оправдание.

Лена считает ____.

-

(9)

— В ломбарде меня точно обманули.

Маша решила ______.

-

(10)

— Я не могу быть преступником.

Вася утверждает _____.

-

(11)

— Я пропущу вечернее собрание из-за простуды.

Аня сказала _____.

-

(12)

— Продавец техники предлагает мне какие-то лишние услуги…

Лена думает _____.

-

(13)

— Все обязаны пройти военную службу.

Главная мысль Пети состоит ____.

-

(14)

— Персонажи попадают в прошлое и пытаются вернуться обратно.

Рассказ Саши основан ______.

-

(15)

— НУ ПОЧЕМУ МОЙ ТРУД НЕ ОЦЕНИЛИ?

Гнев Маши обусловлен _____.

-

(16)

— В детстве меня ругали за любой проступок.

Поведение Лены связано _____.

-

(17)

— Меня никто не хочет слушать…

Реакция Ани вызвана ____.

-

(18)

— Воспитание оказывает огромное влияние на человека.

Вывод Маши заключается ____.

-

(19)

— Ты вел себя неприлично на свидании.

— Да, ты права.

Саша согласился ____.

-

(20)

— Петя, я ничего от тебя не скрываю!

— Лена не рассказывает все свои секреты…

Петя сомневается ____.

-

(21)

— Вася, зачем ты так со мной…

— Я правда не хотел обидеть своего друга.

Вася сожалеет _____.

-

(22)

— Неужели мне предложили место в известной компании!

Аня удивлена ______.

-

(23)

— Я поступила!

— Лену взяли на бюджетное место в лучшем университете страны.

Маша довольна ______.

-

(24)

— Мой рассказ опубликовали в местной газете!

Лена гордится _____.

-

(25)

— Вот бы меня пропустили без очереди в больнице.

Петя надеется _____.

-

(26)

— Половина моих коллег точно уволится к лету.

Саша уверен ______.

-

(27)

— Быть беде, если меня оштрафуют за неправильную парковку.

Вася беспокоится _____.

-

(28)

— А вдруг Петя попадет под сокращение…

Лена боится ______.

-

(29)

— Кошки определенно с другой планеты.

Аня убеждена _____.

-

(30)

— Мне должны повысить зарплату в следующем квартале.

Маша рассчитывает _____.

1.2 A.2 Experiment 2. Experimental sentences

-

(1)

На самом деле мы понимаем, что льготами пользуется не самая бедная часть населения.

-

(2)

На самом деле мы понимаем то, что льготами пользуется не самая бедная часть населения.

На самом деле мы понимаем о том, что льготами пользуется не самая бедная часть населения.

-

(3)

Но всем нам стоит осознать, что ситуация с чтением у нас не так хороша, как мы привыкли думать.

Но всем нам стоит осознать то, что ситуация с чтением у нас не так хороша, как мы привыкли думать.

Но всем нам стоит осознать о том, что ситуация с чтением у нас не так хороша, как мы привыкли думать.

-

(4)

Оппозиция не смогла доказать, что она помогает простым людям выжить и защищает именно их интересы.

Оппозиция не смогла доказать то, что она помогает простым людям выжить и защищает именно их интересы.

Оппозиция не смогла доказать о том, что она помогает простым людям выжить и защищает именно их интересы.

-

(5)

Эксперты не отрицают, что страны Юго-Восточной Азии продолжат увеличивать потребление нефти.

Эксперты не отрицают то, что страны Юго-Восточной Азии продолжат увеличивать потребление нефти.

Эксперты не отрицают о том, что страны Юго-Восточной Азии продолжат увеличивать потребление нефти.

-

(6)

Этот перекрёстный анализ подтвердил, что многие выпускники действительно едут за образованием.

Этот перекрёстный анализ подтвердил то, что многие выпускники действительно едут за образованием.

Этот перекрёстный анализ подтвердил о том, что многие выпускники действительно едут за образованием.

-

(7)

Ни один филолог не может опровергнуть, что язык в современном мире меняется очень быстро.

Ни один филолог не может опровергнуть то, что язык в современном мире меняется очень быстро.

Ни один филолог не может опровергнуть о том, что язык в современном мире меняется очень быстро.

-

(8)

Представители авиакомпании считают, что эта услуга поднимет развлечения во время рейсов на новый уровень.

Представители авиакомпании считают то, что эта услуга поднимет развлечения во время рейсов на новый уровень.

Представители авиакомпании считают о том, что эта услуга поднимет развлечения во время рейсов на новый уровень.

-

(9)

Я решила, что вместе с ним больше никогда в жизни не выйду на сцену.

Я решила то, что вместе с ним больше никогда в жизни не выйду на сцену.

Я решила о том, что вместе с ним больше никогда в жизни не выйду на сцену.

-

(10)

Мальчик представил, что по этому большому помещению тянутся ровные ряды станков и люди что-то точат.

Мальчик представил то, что по этому большому помещению тянутся ровные ряды станков и люди что-то точат.

Мальчик представил о том, что по этому большому помещению тянутся ровные ряды станков и люди что-то точат.

-

(11)

Иногда я воображаю, что хорошая работа может спасти целое население или захватить мир позитивными эмоциями.

Иногда я воображаю то, что хорошая работа может спасти целое население или захватить мир позитивными эмоциями.

Иногда я воображаю о том, что хорошая работа может спасти целое население или захватить мир позитивными эмоциями.

-

(12)

Я сразу сообразила, что никогда в жизни не будет больше такого случая прославиться на всю школу.

Я сразу сообразила то, что никогда в жизни не будет больше такого прекрасного случая прославиться на всю школу.

Я сразу сообразила о том, что никогда в жизни не будет больше такого прекрасного случая прославиться на всю школу.

-

(13)

Мы полагаем, что осуществление обоих протоколов способствовало бы укреплению стабильности в нашем регионе.

Мы полагаем то, что осуществление обоих протоколов способствовало бы укреплению стабильности в нашем регионе.

Мы полагаем о том, что осуществление обоих протоколов способствовало бы укреплению стабильности в нашем регионе.

1.3 A.3 Experiment 2. Fillers

Acceptable fillers

-

1.

Адвокат тихо сказал, чтобы он написал доверенность на кого-то дееспособного.

-

2.

В первую очередь это говорит о том, что мы можем успешно развиваться и повышать свой статус.

-

3.

Мы надеемся на то, что вы по-прежнему будете писать нам письма, рассказывать о себе.

-

4.

Просто родителям хотелось, чтобы их дети подольше оставались девочками и мальчиками.

-

5.

Его не удивило то, что траву сразу же вывозят возами со скошенного луга.

-

6.

Трудность состоит в том, что на нашу тему написано очень мало литературы.

-

7.

В интервью она заявила, что заплатила обществу за свои ошибки.

-

8.

Его не обижало то, что главнокомандующий не сказал ему ничего о своих планах.

-

9.

Год назад всех нас предупредили, что зачисление в 10-й класс будет по итогам экзаменов.

-

10.

Больше всего меня возмущает то, что засыпает он мгновенно и на сколько угодно.

-

11.

И никто не догадался, что старичку трудно одному везти такую тяжелую тележку.

-

12.

ООН предложил, чтобы участники этой конвенции взяли на себя три обязательства.

Unacceptable fillers

-

1.

Археологи проверяют, что эти вещи изготавливали на досуге местные крестьяне.

-

2.

Они желают, что высшее образование перестало быть инструментом общественного неравенства.

-

3.

В спорных ситуациях он всегда давит, что он сирота.

-

4.

Ваших подзащитных обвинили, что они совершили особо тяжкое преступление.

-

5.

Я надеюсь, чтобы он и вправду смог сделать это на виду у всего класса.

-

6.

Основная проблема для данного жанра сейчас заключается, что интернет ― молодежная среда.

Appendix B: Outputs for the models and pairwise comparisons

Appendix C: Additional figures

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Knyazev, M., Ustinova, I. The role of case and presuppositionality in the distribution of to čto-clauses in colloquial Russian: an experimental study. Russ Linguist 47, 87–121 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-023-09271-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-023-09271-2