Abstract

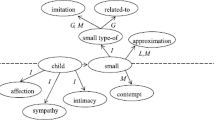

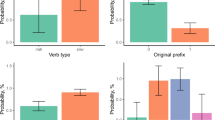

In this article, I will investigate the Old Church Slavonic verbs with the -nǫ suffix, both the verbs that keep the nasal suffix throughout the paradigm (e.g. plinǫti ‘spit’) and the verbs that display -Ø in the past tense (e.g. pogybnǫti ‘perish’). Do these verbs constitute one or more linguistic categories? Having compiled a complete database of relevant verbs in Old Church Slavonic, I will argue for a compromise, according to which all nǫ-verbs belong to the same category network, but display different centers of gravity (prototypes) within this network. The network hypothesis is corroborated by detailed statistical analysis (called ‘linguistic profiling’), which takes both semantic as well as formal properties of the verbs in question into account.

Аннотация

Данная статья посвящена старославянским глаголам с суффиксом -nǫ. В статье рассматриваются и глаголы, сохраняющие суффикс во всей парадигме (напр., plinǫti), и глаголы, в которых суффикс -nǫ в формах прошедшего времени чередуется с нулевым суффиксом (напр., pogybnǫti). Образуют ли эти глаголы одну или несколько лингвистических категорий? Для ответа на этот вопрос была составлена исчерпывающая база данных, включающая все старославянские глаголы на -nǫ. Анализ базы данных позволяет утверждать, что все глаголы на -nǫ принадлежат к одной категориальной сети, но имеют разные центры тяжести (прототипы) внутри этой сети. Сетевая гипотеза находит подтверждение в подробном статистическом анализе (‘лингвистическое профилирование’), при котором учитываются и семантические, и формальные характеристики соответствующих глаголов.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In order to make this article accessible for linguists with little background in statistics, details about statistical analysis will be reported in footnotes. The main statistic test employed in the present study is Pearson’s Chi-squared test. This test yields a p-value that indicates statistical significance, i.e. the likelihood that the observed distribution is due to chance. The lower the p-value, the more significant the result. However, it is important to note that even a highly significant result does not necessarily imply that a factor has a strong impact. Imagine, for instance, a diet that consistently reduces people’s weight. In such a case, the p-value will be very low, but this does not mean that the effect of the diet is strong—in fact the observed weight differences can be both statistically significant and negligible in size at the same time. In order to rule out such situations, Cramer’s V-value, which is a measure of effect size, is computed in all cases where Pearson’s Chi-squared test indicates statistical significance (or, at least, is close to statistical significance). All statistical tests are carried out in the freely downloadable software package R. In the case of Table 1, Pearson’s Chi-squared test (X-squared = 12.2398, df = 6) gives p-value = 0.06, which indicates that there is 6 % chance that the observed differences are due to chance. According to standard practice, p-value = 0.05 is regarded as the threshold for statistical significance, so the result in Table 1 is in the borderline area between significance and insignificance. Cramer’s V-value = 0.1. This indicates a small effect size; even though Cramer’s V-value can theoretically vary between 0 and 1, 0.5 is considered high, while 0.3 represents a moderate value and 0.1 a low value (cf. King and Minium 2008, 327–329).

Examples are cited in transliteration, and provided with an English translation. Examples from Codex Marianus are excerpted from the PROIEL corpus. Examples from Codex Assemanianus, Codex Suprasliensis and Savvina kniga are cited from Corpus Cyrillo-Methodianum Helsingiense. For the convenience of the reader, references to printed editions as given by Aitzetmüller (1977) are provided in parentheses. In quotes from the Bible, book, chapter and verse are given in addition.

Of course, a more fine-grained analysis is conceivable, say, with five categories: ‘pure Ø-verbs’, ‘predominantly Ø-verbs’, ‘vacillating verbs’, ‘predominantly nasal verbs’ and ‘pure nasal verbs’. This option was not chosen because of the limited size of the database. With limited data available too many categories would jeopardize statistical analysis.

Pearson’s Chi-squared test (X-squared = 110.2786, df = 8) gives p-value < 2.2e-16. This is the smallest number the software package R operates with (0…22 with fifteen zeros before 22), so for all practical purposes the likelihood that the differences observed in Table 2 should be due to chance equal zero. Cramer’s V-value = 0.3, which indicates a moderate effect size.

It must be admitted that it is hard to pinpoint the exact meaning of this Gothic loanword, which is attested in Codex Suprasliensis, but not in the semantically more transparent Biblical texts. Lunt glosses goneznǫti as ‘avoid’ (Lunt 1969) and ‘be rid of’ (Lunt 2001, 129), while Cejtlin et al. (1999) provide the Russian synonyms osvobodit’sja, spastis’, izbavit’sja ot kogo-l. / čego-l., izbežat’ čego-l. and Sadnik and Aitzetmüller (1955) the following German equivalents: genesen, entgehen, sich retten, jdm. verborgen sein. At least in examples of the following type, where goneznǫti appears to be opposed to pričastiti sę ‘join, become a participant in’, goneznǫti seems to involve a deliberate effort to avoid something, which I interpret as (metaphorical) movement away from something: ne xotęaše s nimi pričastiti sę nъ goneznouti ixъ xotja ‘did not want to join them, but wished to avoid them’. On this basis I have decided to group goneznǫti with motion verbs such as otъběgnǫti and uběgnǫti. The fact that goneznǫti governs the genitive case lends further support to this analysis, since in the words of Lunt (2001, 145) genitive complements are characteristic of verbs “denoting deprivation and the like”, e.g. izběgnǫti ‘avoid’.

For the purposes of the present paper I use the traditional term ‘inchoative’, which is well established in Slavic linguistics (cf. e.g. Schuyt 1990). It should be pointed out that this is somewhat imprecise, insofar as verbs like sъxnǫti ‘become dry’ and mrьknǫti ‘get dark’ strictly speaking do not describe the beginning of a process. A possible alternative is ‘gradative’ (Russian: gradativ, Padučeva 1996, 117).

Since assigning the stative posagnǫti ‘be married’ and povinǫti (sę) ‘obey, be subject to’, as well as the activity verb kanǫti ‘drip’ to the semantic groups in (17a–c)–(20a–c) is not straightforward, these verbs are left aside for the purposes of radial category profiles.

Pearson’s Chi-squared test (X-squared = 362.4751, df = 6) gives p-value < 2.2e-16. Cramer’s V-value = 0.6.

Pearson’s Chi-squared test (X-squared = 106.7875, df = 2) gives p-value < 2.2e-16. Cramer’s V-value = 0.3.

Pearson’s Chi-squared test of the numbers in Table 8 for high-frequency verbs (the numbers in parentheses) gives p-value < 2.2e-16 (X-squared = 724.1319, df = 6). Cramer’s V-value = 0.8.

References

Aitzetmüller, R. (1977). Belegstellenverzeichnis der altkirchenslavischen Verbalformen (Monumenta linguae slavicae dialecti veteris. Fontes et dissertationes, XI). Würzburg.

Cejtlin, R. M. et al. (Eds.) (1999). Staroslavjanskij slovar’ (po rukopisjam X–XI vekov). Moskva.

Dickey, S. M. (manuscript). Verbal aspect in Late Common Slavic.

Diels, P. (1963). Altkirchenslavische Grammatik. Mit einer Auswahl von Texten und einem Wörterbuch. I. Teil: Grammatik (2nd ed.). Heidelberg.

Divjak, D., & Gries, S. T. (2006). Ways of trying in Russian: clustering behavioral profiles. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory, 2(1), 23–60. doi:10.1515/cllt.2006.002.

Dostál, A. (1954). Studie o vidovém systému v staroslověnštině. Praha.

Eckhoff, H. M., & Janda, L. A. (manuscript). Grammatical profiles and aspect in Old Church Slavonic.

Gorbachov, Ya. V. (2007). Indo-European origins of the nasal inchoative class in Germanic, Baltic and Slavic. Ph.D. dissertation. Harvard.

Janda, L. A., & Lyashevskaya, O. (2011). Grammatical profiles and the interaction of the lexicon with aspect, tense and mood in Russian. Cognitive Linguistics, 22(4), 719–763.

Janda, L. A., & Lyashevskaya, O. (forthcoming). Semantic profiles of five Russian prefixes: po-, s-, za-, na-, pro-. Journal of Slavic Linguistics.

Janda, L. A., & Solovyev, V. D. (2009). What constructional profiles reveal about synonymy: a case study of Russian words for sadness and happiness. Cognitive Linguistics, 20(2), 367–393. doi:10.1515/COGL.2009.018.

King, B. M., & Minium, E. W. (2008). Statistical reasoning in the behavioral sciences. Hoboken.

Lakoff, G. (1987). Women, fire, and dangerous things. Chicago.

Leskien, A. (1922). Handbuch der altbulgarischen (altkirchenslavischen) Sprache. Grammatik – Texte – Glossar (6th ed.) (Indogermanische Bibliothek. Sammlung indogermanischer Lehr- und Handbücher. I. Reihe: Grammatiken, 15). Heidelberg.

Lunt, H. G. (1969). Old Church Slavonic glossary (corrected reprint). Cambridge.

Lunt, H. G. (2001). Old Church Slavonic grammar (7th rev. ed.). Berlin, New York.

Nesset, T., Endresen, A., & Janda, L. A. (2011). Two ways to get out: radial category profiling and the Russian prefixes vy- and iz-. Zeitschrift für Slawistik, 56(4), 377–402.

Nesset, T., & Makarova, A. (2012). ‘Nu-drop’ in Russian verbs: a corpus-based investigation of morphological variation and change. Russian Linguistics, 36(1), 41–63.

Padučeva, E. V. (1996). Semantičeskie issledovanija. Semantika vremeni i vida v russkom jazyke. Semantika narrativa. Moskva.

Plungian, V. A. (2000). ‘Bystro’ v grammatike russkogo i drugix jazykov. In L. L. Iomdin & L. P. Krysin (Eds.), Slovo v tekste i v slovare. Sbornik statej k semidesjatiletiju akademika Ju. D. Apresjana (pp. 212–223). Moskva.

Sadnik, L., & Aitzetmüller, R. (1955). Handwörterbuch zu den altkirchenslavischen Texten. The Hague.

Schuyt, R. (1990). The morphology of Slavic verbal aspect. A descriptive and historical study (Studies in Slavic and General Linguistics, 14). Amsterdam, Atlanta.

Shevelov, G. Y. (1965). A prehistory of Slavic. The historical phonology of Common Slavic. New York.

Stang, C. S. (1942). Das slavische und baltische Verbum. Oslo.

Stefanowitsch, A., & Gries, S. T. (2003). Collostructions: investigating the interaction between words and constructions. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 8(2), 209–243.

Taylor, J. R. (2003). Linguistic categorization. Oxford.

Vaillant, A. (1966). Grammaire comparée des langues slaves. Tome III: Le verbe. Paris.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I am indebted to Henning Andersen, Stephen Dickey, Laura Janda and audiences in Oslo and Moscow for comments on earlier versions of this study. I would also like to thank my colleagues in the CLEAR research group (Cognitive Linguistics: Empirical Approaches to Russian) at the University of Tromsø for valuable input. This article was written while I was a fellow at the Centre for Advanced Study (CAS) at the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters in Oslo. The support from CAS is gratefully acknowledged.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nesset, T. One or several categories? The Old Church Slavonic nǫ-verbs and linguistic profiling. Russ Linguist 36, 285–303 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-012-9093-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-012-9093-3