Abstract

This study’s purpose is to examine whether resilience, conceptualized by Connor and Davidson (2003) as one’s capacity to persevere and rebound under adversity, was a potential mitigating and/or moderating factor in the dynamic between both psychological distress and academic burnout, and student attrition. We concurrently distributed a survey containing a series of psychometric instruments to a convenience sample of 1,119 students pursuing various business majors at four geographically diverse U.S. universities. Via structural equations modeling analysis, we measured the associations between psychological distress, academic burnout, and departure intentions, and investigated whether student resilience levels are associated with lower distress, burnout, and departure intentions levels. The results indicated significant positive associations between psychological distress and each of the elements of academic burnout, and significant positive associations between the academic burnout elements and departure intentions. However, while resilience did not moderate those associations, it did attenuate them through its direct negative associations with both psychological distress and the cynicism and academic inefficacy elements of academic burnout. Based on these findings, we discuss implications for business educators seeking to enhance individual resilience levels as a coping strategy to combat voluntary student turnover, and better prepare students for the demands of the workplace.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Even before the enrollment disruption experienced by colleges and universities worldwide as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, student attrition was a notable concern to educators across many disciplines. Unfortunately, the pandemic has made matters worse. Data from the National Student Research Center (2021) indicate that, as of fall 2021, undergraduate student enrollment has fallen 6.5 percent in total from fall 2019, with few if any signs of recovery on the horizon.

The factors associated with student dropout and retention have been the subject of considerable research for decades. Law and Patil (2015, p. 188) provided a compelling argument for the likely motivation for much of this research by stating “University administrators, faculty, and staff, eager to stem attrition, are understandably interested in areas where they can positively impact retention through measures aimed at improving students’ university experiences.”

In the business world one can presume that the costs of turnover are borne primarily by the employer, especially when the departing employee leaves voluntarily (Griffeth et al., 2000). However, in academia student attrition is often detrimental to all involved parties. For example, students who leave their university prior to graduation negatively affect the institution by lowering its retention rate, a metric often used by government agencies as a key indicator of institutional performance (Yorke, 2000). Other more tangible costs include those attributable to lost tuition income, housing, food, books, fees, loss of financial aid and potential alumni contributions, as well as possible staff layoffs (Natoli et al., 2015). High attrition rates also impact universities in more obscure ways as well. For example, low retention rates may result in an increase in the institution’s cost of capital because of lower bond ratings, and university quality rankings are significantly influenced by graduation and retention rates (Marthers, et al., 2015). Indeed, graduation and retention rates are weighted at over 20% in the rubric used by US News and World Report to calculate their college rankings. Students who leave prematurely may disseminate vitriolic opinions on the institution resulting in long-term adverse reputational effects. Marthers and et al., (2015) suggested that reputational deterioration has the potential to threaten the long-term viability of the institution by inculcating a perception that it is not a “good school”. This perception leads to a vicious circle of fewer applications, and potential students who do apply may be less likely to accept if they have been exposed to the negative opinions of others.

Departing students are negatively impacted by perceptions of failure, reductions in career mobility, and significant reductions in lifetime earnings (e.g., Baum et al., 2010; Law, 2007). Students who drop out have likely paid large sums for tuition and accrued significant debt with little to show for it (Schneider & Yin, 2011). Moreover, recent initiatives intended to address diversity, inclusion and equity issues in the student population will likely “result in greater numbers of ‘at risk’ students, presenting universities with the dual challenges of coping with resource and infrastructure constraints,” while simultaneously attempting to guide these students to degree completion (Levenson et al., 2013, pp. 932–33).

At a societal level, student attrition wastes tax-payer funds and represents the failure of governmental, institutional, and student expenditures to achieve their desired outcomes, thereby resulting in an underutilization of human capital (Levenson et al., 2013; Natoli, et al., 2015). Moreover, student attrition deprives society of a workforce that possesses the specialized knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary to navigate an increasingly complex and technologically focused world (Dewberry & Jackson, 2018).Footnote 1 Perhaps more importantly, Dennison (2020) found that dropping out of college was positively associated with criminal behavior.

College graduates are less likely to collect unemployment than non-graduates. Higher levels of education lead to higher wages and lower unemployment rates. For example, the unemployment rate in 2020 for those that failed to complete any degree was 8.3% compared to those with an associate’s (7.1%), bachelor’s (5.5%), or master’s (4.1%) degree (Torpey, 2021). The unemployment costs paid to dropouts can be added to substantial amounts of lost tax revenue to governmental agencies resulting from lower lifetime wages. Indeed, in 2020 the median weekly wage for those with a bachelor’s degree are about 50% higher ($1,305 vs. $877) than those who fail to attain a degree (Torpey, 2021). Meanwhile, taxpayers continue to fund billions of dollars in appropriations and grants to support students as they pursue goals they will never achieve (Schneider & Yin, 2011).

It is also important to note that the above identified concerns related to individual, institutional, and societal costs are applicable to all types of educational entities regardless of whether they are public or private, or if they are community colleges or universities.

Among management and other business students, studies have found attrition to be associated with a wide range of antecedents including an inability to integrate academically and socially, poor learning experiences, inappropriate choice of major, inadequate academic skills, poor performance, lack of ability to cope with the workload, mediocre pedagogical skills on the part of the faculty, inefficient time management skills, and financial difficulties (Bennett, 2003; Dahlin et al., 2011; Mangum et al., 2005). These factors are consistent with those reported for college students in general (Natoli et al., 2015; Nevill & Rhodes, 2004; Tinto, 1975). Joining the above-noted factors, stress and burnout have received increased attention in recent years among researchers concerned with mitigating college student attrition (Smith et al., 2020a.)

Research into student attrition has shown that psychological stress and burnout are often contributing factors to students’ decisions to drop out (e.g., see Long et al., 2006). Citing DeAngelo and Zimmerman (2005), Klussman et al., (2020, p. 2) emphasized that these factors are “particularly prominent among those focusing their studies on business-related fields.” Illustrative of this point, Dahlin et al. (2011) in a cross-sectional comparative study, reported that business students scored higher than medical students on several stress factors as well as depression and harmful alcohol use. However, while there is a body of prior research on burnout and exhaustion among university students, often among specific majors or fields of study, research into this phenomenon among business students is in its nascence (Law & Patil, 2015). Moreover, there has been little effort to develop a comprehensive model that examines the interplay of antecedents to the student decision to drop out or change major. Law and Patil (2015) pointed out the irony of this situation given the deleterious short-term and long-term consequences that arise as a consequence of student exposure to academic stress and the extensive body of research investigating burnout-related issues among business professionals.

Stress and burnout have been of particular concern to business educators for years. Stixrud (2012, p. 135), citing (Pryor et al., 2011), noted that “Management students face a battle with stress on two fronts, as students themselves – college freshman now report the highest stress and lowest mental health levels in 25 years – and as the next generation of leaders.” Stixrud (2012) further posited that the lessons management students learn in college about managing their stress will help them deal with some of the biggest challenges they will face in their careers. This aligns with DeFrank’s (2012) proposition that much of the stress perceived by employees is caused by their managers, that manager’s stress cascades down to lower-level employees, and the divergent opinions between managers and employees on the causes of workplace stress – all argue for a dedicated management course on stress, it’s sources and impacts, and how individuals and organizations can mitigate its impact. Failure to address stress-related issues in the business curriculum could very well exacerbate workplace problems such as reduced employee productivity, increased stress-related absenteeism and illness, increased stress-related disability costs, family, and relationship problems, etc. (McDaid et al., 2019, as cited in Edwards et al., 2021).

Educators and managers alike are concerned with the well-being of business students (Flinchbaugh et al., 2012). In their research Flinchbaugh et al., (2012, p. 191) characterized well-being as “students’ reduction in stress, enhanced experienced meaning and engagement in the classroom, and, ultimately, heightened satisfaction with life.” In subsequent research Klussman et al. (2020) suggested the solution for educators concerned about high stress and burnout rates among their students is not to simply reduce the stressors that those students experience at the university. They argue this strategy is a temporary solution that does not prepare students for the multitude of stressors they are likely to encounter in the workplace. Rather, educators should consider ways to help students effectively cope with these stressors, i.e., to enhance stress resilience. Researchers have found that resilience can temper the negative influences of stressors (McGillivray & Pidgeon, 2015; Ong, Phinney, et al., 2006; Yeager & Dweck, 2012). Resilience is the ability to persevere and rebound under conditions of stress and adversity (Connor & Davidson, 2003) and resilient individuals have been shown to have increased tolerance to stressors (Connor & Davidson, 2003; Coutu, 2002; Ong, Bergeman, et al., 2006; Smith & Emerson, 2017; Zunz, 1998).

Nearly sixty percent of all students enrolled in public institutions do not graduate within four years (National Center for Education Statistics, 2018). However, resilience has the potential to attenuate the influence of student departure antecedents, and there is ample evidence showing resilience is a malleable trait that can be developed in the classroom (Clauss-Ehlers & Wibrowski, 2007; Steinhardt & Dolbier, 2008; Yeager & Dweck, 2012). Thus, it seems warranted to empirically assess the role that resilience may play as a mitigating factor in the student departure dynamic. The purpose of this paper is to evaluate resilience as a potential coping mechanism that reduces student departure tendencies by overcoming psychological distress and academic burnout. Specifically, we examine resilience and its association with psychological distress and the dimensions of academic burnout, and how these associations ultimately relate to student departure intentions.

The balance of this paper is organized as follows: We begin by presenting our theoretical model. We then describe the constructs contained therein and provide empirical and theoretical justification for the hypothesized structural relationships. We next detail the methods used, including the sample composition and the analytical methodology, followed by presentation of our results. We then discuss the findings and their implications for students, administrators, educators, and researchers. The last section outlines the limitations of our study and concluding observations.

Theoretical Model Conceptualization

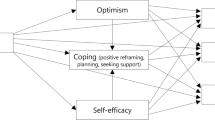

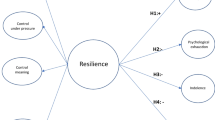

Figure 1 displays the theoretical model, including the hypothesized structural associations between resilience, psychological distress, academic burnout (emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and academic inefficacy), and departure intentions. Prior research in the educational, accounting, organizational behavior, and psychology literature provide the foundation for the theoretical associations, as noted in the model development discussion below. This model illustrates the potential effects of resilience on departure intentions, as mediated by psychological distress and the elements of academic burnout. The mediator constructs thus serve as both predictors and outcomes, thereby acting as the mechanisms through which resilience influences departure intentions.

As Fig. 1 illustrates, the elements of burnout, i.e., emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and academic inefficacy, are predicted to mediate the associations between both resilience and psychological distress, and departure intentions. Prior research (e.g., Fogarty et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2020b) has found that burnout mediates the influence of stressor antecedents on organizational and educational outcomes. However, we cannot discount the possibility that low levels of resilience and high levels of psychological distress will be directly associated with higher departure intention levels, thus these direct associations are tested as part of the structural model evaluation. However, the lack of prior research support for these associations prompted us to formally hypothesize and illustrate only those paths depicted in Fig. 1.

Resilience and its Relationship with Psychological Distress

The association between resilience and psychological distress has been of interest to educational scholars for several years. In an academic context, resilience has been defined as “the heightened likelihood of success in school and other life accomplishments despite environmental adversities brought about by early traits, conditions, and experiences” (Wang et al., 1994, p. 46). Noteworthy for the current study is that despite an increased focus in recent years on resilience as a positive adaptation to adversity in a variety of other contexts, only recently has its role in business student settings garnered serious attention (e.g., Klussman et al., 2021; Sukup & Clayton, 2021).Footnote 2

Resilience is relevant in a myriad of stressful situations in general, and in academic environments in particular (Martin & Marsh, 2006; Ong, Bergeman, et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2020a). If students are unable to effectively deal with the stressors inherent in their academic studies, their performance is likely to suffer leading to the possibility of premature withdrawal from the university (Byrne et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2020b). From an individual perspective, academic stress has been associated with both poor physical and emotional health as well as academic burnout, thus providing additional incentive for the study of resilience in academic settings. In particular, the potential of resilience for enhancing a student’s ability to withstand exposure to stressors will likely enable them to minimize or avoid at least some potential negative repercussions (e.g., Britt & Jex, 2015; Law, 2010). In this study we build upon the work of Connor and Davidson’s (2003) conceptualization of resilience as an individual-level characteristic that helps one to cope with adverse circumstances, stimulates adaptation, and lessens the negative influence of stress (Luthar et al., 2000; Wagnild & Young, 1993; Wang et al., 1994; Zunz, 1998).

The link between resilience and psychological distress has empirical support in studies of college student and general adult population samples. For example, Beasley et al. (2003) found a significant negative association between resilience and psychological distress among a sample of graduate and undergraduate university students. Similarly, Hartley (2011) identified a positive association between resilience and the mental health of undergraduate students experiencing psychiatric disabilities. Finally, Haddadi and Besharat (2010) found with a sample of college students a positive association between psychological health and resilience, and a corresponding negative association between psychological distress and resilience. This evidence prompts the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

Resilience is negatively associated with psychological distress.

Resilience and Academic Burnout

Resilience is also directly related to burnout and is particularly relevant in an academic context. Burnout is a state of emotional, mental, and physical exhaustion resulting from prolonged exposure to excessive stress (Maslach, 1982). A stressful academic climate often triggers the need for students to mobilize the requisite psychological resources to cope with the situation. When students’ coping resources become overwhelmed as a consequence of extended contact with stressors, academic burnout can result (Almer & Kaplan, 2002; Cordes & Dougherty, 1993; Maslach, 1982). Indeed, as burnout symptoms advance, students may experience exhaustion, depression, cynicism, low motivation, poor self-esteem, and other dysfunctional consequences (Cordes & Dougherty, 1993; Smith et al., 2017).

Maslach (1982) proposed three specific dimensions of burnout in adults: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment. Emotional exhaustion is the feeling that one’s emotional resources are depleted and an associated overall lack of energy (Cordes & Dougherty, 1993). Depersonalization is expressed with an uncaring attitude toward others and feelings of emotional detachment. Finally, reduced personal accomplishment is characterized by low motivation, the inability to perform in a competent manner, and a lack of self-esteem (Cordes & Dougherty, 1993; Smith et al., 2017).

In a student context, academic burnout includes the following elements: 1) Exhaustion – the feeling of being overburdened and fatigued by one's studies; 2) Cynicism – taking an indifferent or distant mindset towards one’s studies; and 3) Academic EfficacyFootnote 3 – a feeling of contentment associated with prior and current accomplishments and expectations of continued effectiveness (Maslach et al., 2016).

Luthar et al. (2000) noted that resilience can be conceptualized as a positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity, while Martin and Marsh (2008) posited that such an adaptation could help an individual maintain psychological health by effectively dealing with challenges, setbacks, and other stressors. Higher levels of resilience have been associated with reduced anxiety and depression levels, as well as lower levels of other negative psychological symptoms (e.g., Campbell-Sills et al., 2006; Steinhardt & Dolbier, 2008). Related research has shown that resilience can exert a negative influence on burnout among both working professionals (Smith, et al., 2020b) and students (Smith et al., 2020a), and Zunz (1998) found that resilience-related personal protective factors were negatively associated with the individual components of burnout. Consequently, we expect that resilience will exert a negative influence on the elements of academic burnout. This leads to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2a

Resilience is negatively associated with emotional exhaustion.

Hypothesis 2b

Resilience is negatively associated with cynicism.

Hypothesis 2c

Resilience is negatively associated with academic inefficacy.

Psychological Distress and Burnout

Virtually all college students experience academic stress at some level (Law, 2013; Law & Patil, 2015). Academic stress can lead to psychological distress and burnout, often resulting in students leaving school prior to the completion of their degree (McGillivray & Pidgeon, 2015). The relationship between psychological distress and academic burnout has also been explored. For example, studies have found that protracted exposure to academic stressors results in exhaustion, cynicism, and lower levels of self-efficacy in the affected students (e.g., Schaufeli et al., 2002). Moreover, exam stress, excessive workloads, uncertainty about future employment opportunities, managing the competing demands of coursework, athletics and other extramural activities, deleterious health challenges (particularly the recent COVID-19 virus) as well as insecurities related to finances and tuition increases have all been linked to burnout (Law, 2010; Smith et al., 2014).

As shown in Fig. 1, the three core elements of academic burnout are posited as consequences of psychological distress. However, it should be noted that the elements of burnout have also been theorized and empirically shown in prior research to be antecedents of psychological distress. For example, Micin and Bagladi (2011) postulated that chronic stress and burnout emanating from excessive demands may lead to harmful effects on psychological health.

In this study, the three elements of burnout were modeled as outcomes, rather than antecedents of psychological distress, a theoretical ordering consistent with prior research in academic settings. For example, Guthrie et al., (1998) found that students’ psychological distress is a meaningful predictor of burnout. Other researchers have also theorized psychological distress as an antecedent of burnout in both academic and professional samples (e.g., Kilfedder et al., 2001; Smith et al., 2020b). The theoretical justification for this ordering rests on the fact that the psychological distress construct, a measure of the short to medium-term reaction to stressors, is a precursor to burnout which in turn reflects the influence of prolonged exposure to those stressors (Goldberg & Williams, 1988; LePine et al., 2005).Footnote 4Footnote 5 Based on the preceding theoretical arguments and findings, this study hypothesizes psychological distress is an antecedent to the three elements of academic burnout:

Hypothesis 3a

Psychological distress is positively associated with emotional exhaustion.

Hypothesis 3b

Psychological distress is positively associated with cynicism.

Hypothesis 3c

Psychological distress is positively associated with academic inefficacy.

Academic Burnout and its Association with Departure Intentions

Scholars have offered numerous reasons for students’ premature departure from their studies. Examples include inappropriate selection of college or major, unfavorable learning experiences, students’ inability to integrate socially or academically, financial difficulties, large class sizes, problems with employment, poor quality of instructors, lack of alignment between teaching methods and preferred learning styles, homesickness, health problems, unacceptable academic performance, and the inability to cope with workloads (e.g., Bennett, 2003; Levenson et al., 2013; Long et al., 2006). All these items have the potential to amplify the stress level of the affected individual thereby increasing the likelihood of psychological distress, burnout, and premature departure from the institution. Moreover, Kelly et al. (2012) noted that student departure intentions were associated with burnout, lack of time management skills, and their inability to handle stress.

Maslach (1982) noted that burned out employees are likely to withdraw from the organization and view their employer in adversarial terms. She further contended if the circumstances that produced the burnout symptoms persist, the affected individuals are likely to seek permanent avoidance by leaving the company. The same logic holds for students experiencing academic burnout. If students are unable to successfully deal with the stress that they are subjected to during their university experiences, they will be more likely to prematurely leave the institution. Law (2007) noted that students experiencing symptoms of burnout are likely to exhibit lower academic performance, increased absenteeism, and a higher likelihood of dropping out. Indeed, Nevill and Rhodes (2004) found that students’ inability to cope with their workload was significantly associated with a higher likelihood of their exit from the institution, and Smith et al. (2020a) found academic burnout was positively related to student departure intentions. Based on the forgoing we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 4a

Emotional exhaustion is positively associated with departure intentions.

Hypothesis 4b

Cynicism is positively associated with departure intentions.

Hypothesis 4c

Academic inefficacy is positively associated with departure intentions.

Smith et al.’s (2020a) findings prompted us to propose that emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and academic inefficacy will fully mediate the associations between both resilience and psychological distress, and student departure intentions. It is possible, however, that high levels of resilience and psychological distress might also exert a direct influence on departure intentions. As illustrated in Fig. 1, these potential associations are also tested. However, our expectation of full mediation prompts us to propose:

Hypothesis 5a

After controlling for emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and academic inefficacy, resilience will have a relatively small or insignificant association with departure intentions.

Hypothesis 5b

After controlling for emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and academic inefficacy, psychological distress will have a relatively small or insignificant association with departure intentions.

Potential Moderating Effects

Windle (2011, p. 159) defined variable-based approaches to the study of resilience as those that “use multivariate statistics to examine the relationships between adversity, outcome, and the protective factors/assets.” He proposed three alternative theoretical models to explain how resilience can alter the effects of adversities (e.g., role stress) on outcomes (e.g., burnout). Figure 1 positions resilience as an exogenous predictor, thus serving as a main effect and falling under Windle’s (2011) compensatory model. Other scholars (e.g., García‐Izquierdo et al., 2018a, b) have examined resilience as a moderator. That is, a factor that could influence the direction or strength of the relationship between psychological/mental states and academic burnout. As a moderator, the variable “would only come into play in high-risk situations provoking an adaptive response…” García‐Izquierdo et al. (2018a, p. 2166). This characterization of resilience falls under Windle’s (2011) protective model description.

García-Izquierdo et al. (2018b) found that resilience moderated the relationship between both emotional exhaustion and cynicism, and ultimately psychological health among a sample of Spanish nursing students.Footnote 6 This study utilized identical resilience and psychological distress measures as those used in this study. In contrast, Smith and Emerson (2021), using identical measures, found among a sample of accounting students that resilience only moderated one of the paths between the elements of burnout and psychological distress and that the predictive ability of the model was enhanced with resilience serving as an exogenous predictor rather than a moderator.

If resilience serves as a moderator of psychological stress, students with high resilience scores (compared to students with low resilience scores) will report lower levels of emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and academic inefficacy when they manifest high levels of psychological distress. Similarly, if resilience serves as a moderator of the dimensions of academic burnout, students with high resilience scores will exhibit lower levels of departure intentions relative to their low-resilience counterparts when they report high levels of the academic burnout dimensions. Formally stated (though not graphically illustrated in Fig. 1)Footnote 7:

Hypotheses 6a → c.

Resilience will serve as a moderator in the associations between psychological distress and each of the academic burnout elements – emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and academic inefficacy.

Hypotheses 7a → c.

Resilience will serve as a moderator in the associations between each of the academic burnout elements – emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and academic inefficacy—and student departure intentions.

Methods

Participants

The respondents are a convenience sample of 1,119 students pursuing various business majors at four U.S. universities: 173 at a private university in the West, 311 and 294 at two public universities in the South, and 341 at a public university on the East Coast. All four of the business schools at these universities are accredited by the AACSB. The study’s instrument package was approved by each university’s Institutional Review Board and data collection was concurrently administered in class at each school. The questionnaire was administered by proctors, and the instructions provided students assurances of anonymity. Scale ordering was varied in an effort to mitigate common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2012).Footnote 8

The demographic profile of the respondents presents a relatively balanced cross-section of undergraduate business students. A total of 583 of those reporting gender were males, and 501 were females. Of the 1,099 students reporting age, 921 (84 percent) were between 19 and 24 years old. The sample consisted of 356 sophomores and 530 juniors, approximately 81 percent of the 1,099 students who reported academic level.

Measures

Resilience

The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale-10 (CD-RISC 10: Campbell-Sills & Stein, 2007) was used to measure resilience, as it was in the foundational studies that motivated this investigation. The CD-RISC 10 is a self-report measure that has been extensively used to assess clinical, academic, and professional populations in diverse cultures. Campbell-Sills and Stein (2007, pp. 1026–1027) specify that the CD-RISC 10 “captures the core features of resilience;” i.e., “the ability to tolerate experiences such as change, personal problems, illness, pressure, failure, and painful feelings.” The scale queries respondents as to the frequency each of the 10 items apply to them over the past month on a five-point scale that ranges from 0 (not true at all) to 4 (true nearly all of the time). The scale items assess self-perceptions of one’s ability to cope with adversity/hardships, adapt to change, and stay focused. The higher one’s score, the higher that person’s reported resilience.

Psychological Distress

Consistent with the research motivating this study, the psychological distress construct was measured using the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12: Goldberg, 1978). This construct/scale was developed to screen for psychological stress in the general population (Goldberg & Williams, 1988) and is an established measure of anxiety, somatic symptoms, and social withdrawal (Jackson, 2007). The GHQ-12 has been widely used in a variety of research settings.

Widespread use of the GHQ-12 in clinical and research settings notwithstanding, the scale’s dimensionality remains an issue of widespread controversy. While Goldberg and Williams (1988) designed the scale to be a unidimensional measure, multiple studies over the ensuing years have also found support for two and three factor models (for a review, see Hystad & Johnsen, 2020). Based on the results of preliminary confirmatory composite analyses of the GHQ-12 items with the present study data, we found that Graetz’s (1991) three-factor model best fit the data. This model consists of three unique lower order constructs (LOCs) labeled Anxiety and Depression, Social Dysfunction, and Loss of Confidence, which in turn are reflective of the higher order construct (HOC) Psychological Distress. Other studies have also found Graetz’s three-factor model to be the best fitting (e.g., Abubakar & Fischer, 2012; Gao et al., 2004; Shevlin & Adamson, 2005; Ye 2020) lending further support for our decision to utilize this factor structure to measure psychological distress.Footnote 9

Academic Burnout

In line with prior research, we assessed academic burnout using the MBI: General Survey – Students (MBI-GS[S]), developed by Maslach et al. (2016) for use with adult students in higher education. The 16-item MBI-GS[S] captures the three elements of burnout: (1) Exhaustion (5 items); (2) Cynicism (5 items); and (3) Academic Inefficacy (6 items).Footnote 10

Departure Intentions

Departure intentions were obtained using three items adapted from Donnelly and Ivancevich (1975) to an academic context. The questions queried students as to how often they thought about “looking for a new major or university”, “quitting”, or “dropping out of the university”.

Control Variables

Demographic factors such as age, gender, educational level, etc., have been shown to be associated with specific behavioral outcomes in prior research (e.g., Herda & Martin, 2016; Jones et al., 2010). Five demographic controls were included in our analyses to assess their potential influence on the tested associations between resilience, psychological distress, and academic burnout. These control factors are displayed in Table 1 as Constructs 1–5.

Table 1 displays the inter-scale correlations between the control variables and the primary study constructs, which were non-significant with a few exceptions: gender significantly correlated with a few of the study constructs, and major was significantly correlated with cynicism.Footnote 11 Boehm et al. (2015) and Becker (2005) argued that unnecessary control variables could potentially generate biased parameter estimates, and the exclusion of unnecessary controls maximizes the power of structural modeling tests by decreasing the number of estimated parameters. This motivated the exclusion of all controls from further analysis except gender and business major (as reported below).Footnote 12

Research Design

Podsakoff et al. (2012) indicated that when data are collected from self-report instruments common method variance should be examined, especially when the same individual provides data for both the independent and dependent variables. In addition to the above-referenced survey instrument distribution protocol, Harman’s single factor test (Harman, 1976) was conducted to ascertain whether a single factor accounted for most of the covariance in the model. Several explanatory factors were identified by means of a principal components analysis of the sample data, thus rejecting the single factor explanation. In addition, while some studies have suggested the Harman approach (Harman, 1976) may not detect the presence of common method bias, more recent research indicates it is a quite meaningful method (Babin et al., 2016). Finally, the discriminant validity tests of the measurement model constructs reported below provided additional assurance that common method variance is not a meaningful issue in the present study.

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) using SmartPLS 3.0 software was applied to assess the hypothesized theoretical model. Manley et al. (2021) specify ten situations where the application of PLS-SEM is appropriate. This study meets the requirements for several of these, including: 1) it extends a theory; 2) it includes multiple-item latent variables; 3) the model is complex and includes many constructs, indicators, and/or causal relationships; and 4) a primary objective of the research is prediction. As is typical for structural equation modeling analysis, the two-step process recommended by Anderson and Gerbing (1988) was followed, along with the confirmatory composite analysis (CCA) procedure (Hair et al., 2020). The first step confirms the measurement model, and the second step evaluates the structural model results.

Results

This study utilized the disjoint two-stage approach advocated by Becker et al. (2012) for estimating measurement and structural models that incorporate higher order constructs.Footnote 13 During the first stage, each of the lower-order components of psychological distress, i.e., Anxiety and Depression, Social Dysfunction, and Loss of Confidence (without the higher-order psychological distress factor) are linked to the hypothesized antecedent (i.e., resilience) and consequent factors (i.e., each of the elements of academic burnout) to assess internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity among the constructs.

The second stage commences by assessing the reflective measurement model for the higher order component Psychological Distress. As Sarstedt et al., (2019, p. 3) prescribe, this is accomplished by saving the latent variable scores from the first stage analysis for the three above-referenced subscales, which are used to measure the Psychological Distress construct – all other path model contstructs are measured using the same multi-item measures used in the first stage. Afterward, the structural model associations are evaluated.

Measurement Model Assessment

We began our analysis by evaluating the validity of the associations between the indicator variables and their associated latent variables as well as the predicted linkages between the underlying constructs. Table 2 presents the results of the Stage 1 reliability and convergent validity assessments of the measurement model constructs. The data supported all three reported internal consistency measures, i.e., Cronbach alpha, rho_A, and Composite Reliability, with values ranging from 0.738 to 0.909, essentially falling within the 0.70 to 0.90 range that Hair et al. (2019) defined as satisfactory to good. As illustrated, all of the individual item loadings exceeded Chin et al.’s (2008) suggested minimum value of 0.60. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each construct exceeded Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) minimum 0.50, thus demonstrating adequate convergent validity.

Table 3 presents the results from the Stage 1 discriminant validity tests that assessed whether the LOCs were empirically distinct from one another (Hair et al., 2019). As illustrated, all Henseler et al. (2015) ratios of correlations were below the authors’ prescribed threshold of 0.85 for conceptually dissimilar constructs, and significantly lower than 0.90 (for a discussion of HTMT cutoff values, see Franke & Sarstedt, 2019). As can be seen from the results of Henseler et al.’s (2015) suggested 5,000-sample bootstrapping procedure that generated 95% confidence intervals, none of the interval values illustrated in the last two columns included the value of 1, thus providing additional evidence for discriminant validity.

Though not reported in tabular form, we further addressed the potential that our model is contaminated by common method bias by conducting Kock’s (2015) suggested multicollinearity diagnostic procedure in SmartPLS. This procedure assessed the variance inflation factors (VIFs) for the indictors. According to Kock (2015) VIFs of 3.3 or lower indicate that the model is free of common method bias. None of the VIFs in our model exceeded 2.873, thus providing additional assurance that common method bias was not a cause for concern with our data.

Table 4 presents the results from the Stage 2 analysis of the measurement model for the higher-order construct Psychological Distress. As Panel A illustrates, the reported Cronbach alpha and rho_A values are just below Hair et al.’s (2020) suggested minimum of 0.700. However, as indicated, a 5,000-sample bootstrapping procedure which generated 95% confidence intervals produced upper range values above 0.700 for both measures. In addition, the composite reliability value of 0.831 falls within Hair et al.’s (2020) suggested range of 0.70–0.95, supporting the internal consistency for the HOC. The average variance extracted value of 0.669 is higher than the suggested minimum, thus supporting the convergent validity of the construct indicators. As Panel B illustrates, discriminant validity among the constructs is supported as none of the individual ratio of correlations is higher than 0.595, and all are significantly below 0.85.

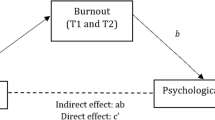

The loadings of the first order constructs on the second order Psychological Distress construct (illustrated in Fig. 2 below) supported the latter’s conceptualization as a reflective-reflective second-order factor. The loading for Anxiety and Depression was 0.821 (t-value = 63.043; p < 0.01), the loading for Loss of Confidence was 0.847 (t-value = 84.570; p < 0.01), and the loading for Social Dysfunction was 0.690 (t-value = 26.620; p < 0.01).

Structural Model Evaluation

After establishing the reliability and validity of the lower-order constructs in Stage 1, and the higher order Psychological Distress construct in Stage 2, the analysis of the structural model began. Table 5 presents the results of the hypothesis tests and structural model evaluation. We calculated R2, effect size (f2), and in-sample predictive relevance (Q2) metrics and assessed the structural model by examining the structural (i.e., beta) coefficients and their corresponding t-values using Hair et al.’s (2017) 5,000 resample bootstrapping procedure. As Table 5 indicates, resilience had a significant negative association with psychological distress supporting H1. Resilience also had significant direct negative associations with cynicism and academic efficacy, but not emotional exhaustion, thus supporting Hypotheses 2b and 2c, but not 2a. Psychological distress had significant direct negative associations with emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and academic efficacy, supporting Hypotheses 3a → 3c. In turn, each of the academic burnout dimensions a significant positive association with departure intentions, thus supporting Hypotheses 4a → 4c. As predicted, resilience did not have a significant direct association with departure intentions, thus supporting Hypothesis 5a. However, psychological distress had a significant direct positive association with departure intentions, failing to support Hypothesis 5b.

Hair et al. (2016) recommend the f2 effect-size metric to assess how the removal of a particular predictor construct affects an endogenous construct’s R2 value. Cohen (1988) prescribed that f2 values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 represent small, medium, and large effect sizes. Ali et al. (2016) advocated the f2 value be reported as a substantive significance measure along with statistical significance (p) values. As Table 5 also indicates, six of the significant path coefficients had small effect sizes, and two had a medium effect.

Figure 2 presents a visual representation of the results of our structural model tests. The R2 values indicate resilience explained 17.9 percent of the variance in psychological distress, and resilience and psychological distress explained 21.7, 16.5 and 21.8 percent of the variance in emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and academic inefficacy, respectively. Most importantly, our model explained nearly thirty percent of the variance in student departure intentions.

Hair et al. (2019) indicate predictive accuracy of a PLS path model should also be assessed using the Q2 statistic. Shmueli et al. (2019) and Sarstedt et al. (2017) indicate that in-sample predictive accuracy of a structural model can be shown when the blindfolding Q2 values associated with specific endogenous construct are greater than zero. Figure 2 also illustrates the Q2 values for psychological distress, emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and academic efficacy. These values support the in-sample predictive relevance of the model for each construct.

Shmueli et al., (2019, p. 2323) argue that “assessing a statistical model’s predictive power is a crucial element of any study.” PLS-SEM can concurrently assess both explanation and prediction, and “PLS results are well-suited to generate out-of-sample predictions.” To assess the final structural model’s out-of-sample predictive power, we followed Shmueli et al.’s (2019) suggested procedure and used the PLSpredict option in SmartPLS. We assessed the key prediction statistics by specifying 10 folds and 10 repetitions for generating the training and holdout samples for estimating model parameters. We then compared the RMSE and MAE values of the PLS path model to those of a linear benchmark model. The results of these analyses appear in Table 6.Footnote 14

Shumeli et al. (2019) suggest that when interpreting PLSpredict results, one should focus on the indicators of the model’s key endogenous construct rather than evaluating the prediction errors of all the model’s endogenous constructs’ indicators. In accordance with that guideline, Table 6 reports the prediction error metrics for this study’s key endogenous construct, i.e., departure intentions. Shmueli et al., (2019, p. 2330) guidelines indicate that the PLS-SEM model has medium predictive power if the majority of its indicators have lower predictive errors (i.e., lower RMSE and MAE values) when compared to the linear benchmark model. As illustrated, the PLS-SEM model had lower RMSE and MAE statistics values, and higher Q2predict values than did the linear benchmark model, for departure intentions indicators 2 and 3, thus supporting medium predictive power for the model.Footnote 15

Control Variable Analyses

To further assess the potential impact of the significant correlations between gender and major with specific primary study constructs reported in Table 1, we conducted multi-sample analyses of the structural model. These analyses measured whether there were significant differences in individual path coefficients between females and males, as well as between accounting majors and management majors. The Welch-Satterthwaite test results in SmartPLS failed to uncover any significant inter-major path coefficient differences. However, these tests revealed two significant gender differences: the path coefficient between academic inefficacy and departure intentions for males (0.249) was significantly higher than that for females (0.141), and the coefficient between psychological distress and cynicism for females (0.400) was significantly higher than that for males (0.264). However, given that both paths are significant and in the same direction for both females and males, and congruent with the corresponding full-sample path coefficients, these could very well be distinctions without a difference. Thus, these findings provided reasonable assurance that neither of these controls confounded the tested relationships among the primary study constructs.

Mediation (Indirect Effects) and Moderation Analyses

As reported in Table 5, resilience did not have a significant direct association with emotional exhaustion or departure intentions. To better understand the mediating effects of psychological distress (on resilience) and emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and academic inefficacy (on resilience and psychological distress), we performed a path-analytic decomposition of the direct and indirect effects of resilience and psychological distress on each outcome (Sarstedt et al., 2020).Footnote 16 As Table 7 indicates, resilience has a significant indirect negative association with emotional exhaustion (β = -0.193; t = 10.625; p < 0.01) through its direct negative association with psychological distress (-0.424 * 0.454 = -0.193). Also, while resilience has significant direct negative associations with cynicism and academic inefficacy, it also has significant negative indirect associations with both constructs through its association with psychological distress for total effects of -0.272 and -0.431, respectively. Resilience has a significant indirect negative association with departure intentions (-0.231) through its direct association with psychological distress, and its direct and indirect associations with the elements of academic burnout. Finally, psychological distress also has a significant indirect association with departure intentions (0.206) via its direct positive association with each academic burnout element for a total effect of 0.311.

We next tested the hypothesized moderating effects for resilience using both the product indicator and two-stage approaches described by Hair et al. (2022).Footnote 17 For these analyses, we used standardized indicators as suggested by the authors to reduce collinearity in the path model. Though not reported in tabular form, no significant moderating effects for resilience were measured, thus failing to support H6a → c and H7a → c.

Discussion

We had a dual motivation for this study. First was to evaluate the efficacy of resilience in reducing business student departure intentions, and at the same time to explore whether the deleterious effects of psychological distress were associated with academic burnout and ultimately departure intentions. Second, based on prior literature, we wished to ascertain whether resilience served as either a moderator in the psychological distress / academic burnout / departure intentions dynamic, or as an exogenous predictor of these proposed relationships.

Our findings support the Fig. 1 conceptualization of resilience as a coping mechanism with the potential to reduce psychological distress and academic burnout among business majors, ultimately resulting in an overall decline in reported students’ intentions to voluntarily withdraw from their studies – regardless of their current psychological distress or burnout levels. Moreover, in addition to the above-referenced direct associations, resilience is also indirectly associated with cynicism and academic inefficacy, as mediated by psychological distress. The positive direct associations between psychological distress and the elements of academic burnout, as well as that between burnout and departure intentions, were also as hypothesized and congruent with prior research (e.g., see García‐Izquierdo, et al., 2018a, 2018b; Kilfedder et al., 2001; Smith et al., 2020b) The analysis of the theoretical model generated favorable results with full support for 10 of the 12 hypothesized associations, and the model explained over 29% of the variance in student departure intentions. We further found that resilience exerted no moderating influence in any of the tested associations between psychological distress and each of the burnout elements nor between each of the burnout elements and departure intentions.

The failure of resilience to have a significant direct association with emotional exhaustion deserves further comment. This finding may be an exemplar of the stress mindset construct (Crum et al., 2013). As interpreted by Klussman et al., (2021, p. 1463), “Individuals who view stress as harmful, known as having a stress-is-debilitating mindset, suffer the negative effects traditionally associated with stress. In contrast, individuals who do not view stress negatively seem to avoid these same negative outcomes. It is, therefore, plausible that students who do not view stress as debilitating may be buffered from the negative effects of stress.” Indeed, in our sample, resilience appears to have a negative association with emotional exhaustion only to the extent that it reduces psychological distress. That is, only those with a stress-is-debilitating mindset appear to be susceptible to emotional exhaustion, i.e., distress appears to be the primary driver of exhaustion. Resilient students may be buffered from the debilitating effects of excessive stress, thus the lack of direct association with exhaustion.

The lack of significant moderating effects for resilience are inconsistent with Windle’s (2011) protective model conceptualization. Instead, the results support Windle’s (2011) notion of resilience as a compensatory (i.e., coping) in nature, with the potential to enhance personal well-being and attenuate voluntary departure from studies among business students, notwithstanding their reported stress and burnout levels.

Our findings also support the theoretical premise of burnout is a consequence of psychological distress. However, a compelling case might also be made for the contention that this association consists of an iterative feedback loop wherein high levels of psychological distress generates symptoms of burnout, which induces higher level of distress, ad infinitum. Given the cross-sectional nature of our data, we believe it would be inappropriate to draw a definitive conclusion about the temporal precedence of either construct.

Implications

Institutions of higher learning, administrators, and educators have long been interested in attracting and enrolling the highest quality students. Moreover, once enrolled, universities want to retain students until they have successfully completed their studies (Tight, 2020). Unfortunately, many students are unable to cope with the demands of university life. Given declining enrollment numbers (National Center for Education Statistics, 2019), it is important to understand the underlying motivations for withdrawal decisions and develop proactive strategies to address them.

Our results suggest higher levels of individual-level resilience are effective in helping students cope with the rigors of college life and reduce departure intentions by ameliorating the detrimental effects of psychological distress and academic burnout. These results further suggest students, educators, and administrators would benefit from increased awareness of the practical advantages that can be gained from targeted resiliency training. Moreover, these benefits can be realized by the entire student population, not just those suffering from the ravages of psychological distress, and/or burnout.

Fortunately, there are several options available to business educators who seek to enhance resilience levels in their students to enhance their well-being and prepare them for the rigors of their studies and the challenges they are likely to face in the workplace. One resilience enhancement tactic is to focus class discussions on how stress can energize students and focus their attention, rather than emphasizing the deleterious aspects of excessive stress (Yeager & Dweck, 2012). Educators may also promote an adaptive stress mindset and self-connection as means of “fostering stress resilience among students” (Klussman et al., 2021). Klussman et al., (2020, p. 1) defined self-connection as “an awareness of oneself, an acceptance of oneself based on this awareness, and an alignment of one’s behavior with this awareness.” This approach thus focuses on: (1) training students to become more self-aware of their reasons for choosing their major; (2) helping students to accept the reasons for selecting their major and what they expect to attain from doing so; and (3) completing the self-connection process by helping students to act in a manner congruent with those motivations and aspirations. The premise of this approach is that students who are more self-connected are more satisfied and less likely to experience personal burnout (Klussman et al., 2021, p. 1473).

Flinchbaugh et al. (2012) advocated for management faculty to consider a multi-faceted approach to enhancing resilience and student well-being in management education classes by using stress management and gratitude journaling techniques. The stress management tactics included deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, and positive self-affirmations. These authors defined gratitude journaling as “individuals regularly identifying specific aspects of their recent life experiences for which they are thankful” (p. 194).Footnote 18 Students indicated these newly learned techniques were effective in preparation for quizzes, group work, and presentations, as well as in other classes. The authors also provided step-by-step instructions for implementing their suggested techniques in the classroom (pp. 211–213).

Other resilience enhancement resources are available to management educators. For example, see the University of Calgary (https://haskayne.ucalgary.ca/future-students/executive/programs-individuals/mental-toughness), Stanford University (https://learningconnection.stanford.edu/resilience-project) and the University of Pennsylvania (https://ppc.sas.upenn.edu/services/penn-resilience-training) training programs for insights on how to enhance student well-being, retention and success.

Limitations and Conclusions

As with all empirical studies, our results must be interpreted in light of their limitations. First among these is our use of a single self-reported survey instrument. Cross-sectional data collected from instruments such as these are subject to the possibility of the negative influence of common methods variance or issues related to instrument design. However, each of the constructs measured with our survey were captured using psychometric scales that have been validated in prior research. In addition, our findings support the distinctiveness and theoretical foundations of our latent variables which suggests our data collection method is not responsible for the observed associations between them.

The cross-sectional design of our study also raises concerns that the data would support construct orderings other than those hypothesized. While all our analyses were conducted in accordance with extant theory and research, conclusive statements regarding causality await future longitudinal studies. Moreover, this study evaluated students’ intentions to leave their studies rather than their actual departure. But, according to Ajzen (1991), the explicit intention to engage in a particular behavior is the best predictor of the behavior occurring. Lastly, given Ungar’s (2008) findings that there are global, cultural, and context-specific aspects of ones’ environment that contribute to their resilience, there is concern our results may not be generalizable to locales outside of the United States.

That resilience failed to moderate the hypothesized associations in this study does not preclude the possibility that it might do so when evaluated with other antecedents of psychological distress and academic burnout such as academic workload, work-school conflict, etc. Our theoretical model, like all models that attempt to reflect real-world phenomena, is limited in terms of explanatory power by the variables chosen for study. We therefore encourage additional studies that extend our model and assess the interplay of resilience with additional antecedents known to influence distress and burnout.

Despite these limitations, our study adds to the extant research on resilience in the context of student retention. We show that individual-level resilience, through its influence on psychological distress and the elements of academic burnout, can exert a dampening effect on departure intentions of students. Given the deleterious impact that student withdrawals have on all the involved parties, any actions that can be taken to minimize them would be a worthwhile exercise.

Moreover, business students should be made aware that even if they themselves currently possess the resources to effectively cope with the stresses of college studies, as future managers they will benefit greatly from learning how to foster individual resilience and well-being in the workplace. In fact, Rock (2009) argued that this skill is necessary to prevent stress-related problems at work from undercutting their success and that of their employees. As Stixrud (2012, p. 135) emphasized, the ability of future managers to effectively handle their own stress responses and engender stimulating yet not overly stressful work environments is a crucial “survival skill” for twenty-first century managers. Prolonged exposure to stressors can have damaging, detrimental and deleterious effects that have the potential to be debilitating, and our results show that resilience may have the ability to ameliorate these negative outcomes. With this backdrop, the addition of resiliency training to the classroom appears to be both timely and propitious.

Notes

It should be acknowledged that not all attrition from a university is detrimental to the departing students. According to the National Center for Education Statistics (2020, p. 114), over 43% of first-time postsecondary students between 2012 and 2017 transferred to a different institution and of those, more than half were migrations between different four-year schools. While transfer students typically have lower graduation rates and GPAs relative to their counterparts who start and complete their degrees at the same institution, they are still likely to graduate (Li, 2010).

A critical review of the literature will also reveal that prior research into resilience, and specific antecedents and consequences of psychological distress and academic burnout, have primarily utilized traditional correlational, path-analytic, and multiple regression techniques. Williams and Hazer (1986, p. 221) state that these methods are susceptible to random measurement error and the biasing effects of method variance which can “attenuate estimates of coefficients, make the estimate of zero coefficients nonzero, or yield estimates with the wrong sign”.

To allow consistent scoring and interpretation across each of the burnout dimensions, we reverse scored the academic efficacy items so the higher the score, the lower the academic efficacy, in effect creating a measure of academic inefficacy.

The instructions for the questions related to psychological health read “We would like to know how your health has been in general, over the past few weeks” (emphasis added) whereas those for the Maslach Burnout Inventory variant utilized in this study read “Read each statement carefully and decide if you ever (emphasis added) feel this way about your studies at the university”.

Smith and Emerson (2021, pp. 247–248) acknowledge that the relationship between psychological distress and academic burnout may be non-recursive, a phenomenon only testable via a study of longitudinal design. That caveat noted, they conclude (p. 248) “resilience appears to have a prophylactic relationship with both constructs, thus pointing to the potential for resilience enhancement strategies as a means of enhancing student mental health and reducing academic burnout”.

Both studies positioned the burnout dimensions as antecedents to psychological health. In the present study the burnout dimensions are positioned as mediators based on the proposed theoretical foundations.

Campbell-Sills and Stein (2007), reporting on their development of the resilience scale used in the present study, found that resilience moderated the impact of childhood maltreatment on current psychiatric symptoms among a sample of 1,743 undergraduate students. Their finding motivated us to re-assess the moderating role of resilience despite the mixed results reported above.

Utilization of self-report measures in a single setting may subject the results to the charge of common method bias, i.e., the tendency of respondents to attempt to maintain consistency of responses to the battery of instruments completed. Below we discuss a statistical technique employed to assess the validity of this concern with our data.

Shevlin and Adamson (2005) and Gnambs and Staufenbiel (2018) and others found little utility of GHQ-12 subscales due to the limited information that they provide beyond the general psychological distress factor. These findings appear to support this study’s structural model conceptualization of psychological distress as a single HOC as opposed to three unique LOCs.

A confirmatory factor analysis of the 16 MBI-GS[S] items with the present sample data indicated that all items loaded on Maslach et al.’s (2016) three underlying dimensions in the expected pattern.

Only the correlation between management and accounting student majors was significant, with management majors exhibiting a higher level of cynicism.

As shown in Table 1, school was also one of the control variables. Given the potential impact of geographic and cultural differences on the responses from the students at the four schools, a supplemental series of analyses of variance were conducted to identify any significant inter-school score differences among any of the primary study constructs. There were none. Therefore, the data from all four schools were aggregated for the subsequent structural modeling assessments.

Sarstedt et al., (2019, p. 2) note that “when sample sizes are sufficiently large” this approach yields similar results to those obtained from using the other two commonly approaches to evaluating HOCs, i.e., the extended repeated indicators approach, and the embedded two-stage approach.

See Shmueli et al. (2019) for a full discussion of prediction statistics that can be used to assess the degree of prediction error.

Shmueli et al. (2019) state that the Q2predict value for each indicator must be greater than zero before the RMSE (and / or MAE) values for the PLS-SEM model can compared to the respective naïve linear benchmark values. As Table 6 illustrates, this criterion is satisfied for all three indicators of the departure intentions factor.

According to Chong and Monroe (2015), referencing Kerlinger and Pedhazur (1973, p. 19), this procedure “can be used to determine whether the pattern of correlations for a set of observations is consistent with a specific theoretical formulation.”.

Memon et al., (2019, p. vii) state “… the decision as to whether there is any moderating effect should be made based on a significant relationship between the moderating effect (Z) and the dependent variable (Y).” Consequently, only Hypotheses 6b and 6c were tested as resilience (i.e., the potential moderating effect) did not have a significant relationship with either emotional exhaustion or departure intentions, precluding the testing of Hypotheses 6a and 7a-c.

Barry et al. (2019) similarly proposed mindfulness practices such as mindfulness mediation to reduce stress and enhance individual well-being.

References

Abubakar, A., & Fischer, R. (2012). The factor structure of the 12-item General Health Questionnaire in a literate Kenyan population. Stress and Health, 28(3), 248–254.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Ali, F., Kim, W. G., & Ryu, K. (2016). The effect of physical environment on passenger delight and satisfaction: Moderating effect of national identity. Tourism Management, 57, 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.06.004

Almer, E., & Kaplan, S. (2002). The effects of flexible work arrangements on stressors, burnout, and behavioral job outcomes in public accounting. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 14(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.2308/bria.2002.14.1.1

Anderson, J., & Gerbing, D. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

Babin, B., Griffin, M., & Hair, J. F., Jr. (2016). Heresies and sacred cows in scholarly marketing publications. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3133–3138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.001

Barry, K. M., Woods, M., Martin, A., Stirling, C., & Warnecke, E. (2019). A Randomized controlled trial of the effects of mindfulness practice on doctoral candidate psychological status. Journal of American College Health, 67(4), 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2018.1515760

Baum, S., Ma, J., & Payea, K. (2010). Education pays 2010: The benefits of higher education for individuals and society. College Entrance Examination Board.

Beasley, M., Thompson, T., & Davidson, J. (2003). Resilience in response to life stress: The effects of coping style and cognitive hardiness. Personality and Individual Differences, 34(1), 77–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00027-2

Becker, T. E. (2005). Potential problems in the statistical control of variables in organizational research: A qualitative analysis with recommendations. Organizational Research Methods, 8(3), 274–289.

Becker, J. M., Klein, K., & Wetzels, M. (2012). Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Planning, 45, 359–394.

Bennett, R. (2003). Determinants of undergraduate student dropout rates in a university business studies department. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 27(2), 123–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/030987703200065154

Boehm, S. A., Dwertmann, D. J., Bruch, H., & Shamir, B. (2015). The missing link? Investigating organizational identity strength and transformational leadership climate as mechanisms that connect CEO charisma with firm performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(2), 156–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.07.012

Britt, T. W., & Jex, S. M. (2015). Thriving under stress: Harnessing demands in the workplace. Oxford University Press.

Byrne, M., Flood, B., & Griffin, J. (2014). Measuring the academic self-efficacy of first-year accounting students. Accounting Education, 23(5), 407–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2014.931240

Campbell-Sills, L., Cohan, S. L., & Stein, M. B. (2006). Relationship of resilience to personality, coping, and psychiatric symptoms in young adults. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(4), 585–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.05.001

Campbell-Sills, L., & Stein, M. B. (2007). Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(6), 1019–1028. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20271

Chin, W. W., Peterson, R. A., & Brown, S. P. (2008). Structural equation modeling in marketing: Some practical reminders. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 16(4), 287–298. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679160402

Clauss-Ehlers, C. S., & Wibrowski, C. R. (2007). Building educational resilience and social support: The effects of the educational opportunity fund program among first-and second-generation college students. Journal of College Student Development, 48(5), 574–584. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2007.0051

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113

Cordes, C. L., & Dougherty, T. W. (1993). A review and an integration of research on job burnout. Academy of Management Review, 18(4), 621–656. https://doi.org/10.2307/258593

Coutu, D. L. (2002). How resilience works. Harvard Business Review, 80, 46–51.

Crum, A., Salovey, P., & Achor, S. (2013). Rethinking stress: The role of mindsets in determining the stress response. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(4), 716–733. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031201

Dahlin, M., Nilsson, C., Stotzer, E., & Runeson, B. (2011). Mental distress, alcohol use and help seeking among medical and business students: A cross-sectional comparative study. BMC Medical Education, 11(1), 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-11-92

DeAngelo, H., DeAngelo, L., & Zimmerman, J. L. (2005). What's really wrong with US business schools? Available at SSRN 766404. https://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.766404

DeFrank, R. S. (2012). Teaching a comprehensive course on stress and work. Journal of Management Education, 36(2), 143–165.

Dennison, C. R. (2020). Dropping out of college and dropping into crime. Justice Quarterly, 1–27.

Dewberry, C., & Jackson, D. J. (2018). An application of the theory of planned behavior to student retention. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 107, 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.03.005

Edwards, M. S., Martin, A. J., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2021). Mental health and psychological well-being among management students and educators. Journal of Management Education, 45(1), 3–18.

Flinchbaugh, C. L., Moore, E. W. G., Chang, Y. K., & May, D. R. (2012). Student well-being interventions: The effects of stress management techniques and gratitude journaling in the management education classroom. Journal of Management Education, 36(2), 191–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562911430062

Fogarty, T. J., Singh, J., Rhoads, G. K., & Moore, R. K. (2000). Antecedents and consequences of burnout in accounting: Beyond the role stress model. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 12, 31–67.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equations models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Franke, G., & Sarstedt, M. (2019). Heuristics versus statistics in discriminant validity testing: A comparison of four procedures. Internet Research, 29(3), 430–447.

Gao, F., Luo, N., Thumboo, J., Fones, C., Li, S. C., & Cheung, Y. B. (2004). Does the 12-item General Health Questionnaire contain multiple factors and do we need them? Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 2(1), 1–7.

García-Izquierdo, M., Meseguer de Pedro, M., Ríos-Risquez, M. I., & Sánchez, M. I. S. (2018a). Resilience as a moderator of psychological health in situations of chronic stress (burnout) in a sample of hospital nurses. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 50(2), 228–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12367

García-Izquierdo, M., Ríos-Risquez, M. I., Carrillo-García, C., & Sabuco-Tebar, E. D. L. Á. (2018b). The moderating role of resilience in the relationship between academic burnout and the perception of psychological health in nursing students. Educational Psychology, 38(8), 1068–1079. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2017.1383073

Gnambs, T., & Staufenbiel, T. (2018). The structure of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12): Two meta-analytic factor analyses. Health Psychology Review, 12(2), 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2018.1426484

Goldberg, D. (1978). GHQ-12. NFER-Nelson.

Goldberg, D. P., & Williams, P. (1988). The user’s guide to the General Health Questionnaire. NFER-Nelson.

Graetz, B. (1991). Multidimensional properties of the general health questionnaire. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 26(3), 132–138.

Griffeth, R. W., Hom, P. W., & Gaertner, S. (2000). A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management, 26(3), 463–488.

Guthrie, E., Black, D., Bagalkote, H., Shaw, C., Campbell, M., & Creed, F. (1998). Psychological stress and burnout in medical students: a five-year prospective longitudinal study. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 91(5), 237–243.

Haddadi, P., & Besharat, M. A. (2010). Resilience, vulnerability and mental health. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Science, 5, 639–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.157

Hair, J. F., Howard, M., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109(5–6), 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.). Sage.

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Harman, H. H. (1976). Modern factor analysis. University of Chicago Press.

Hartley, M. T. (2011). Examining the relationships between resilience, mental health, and academic persistence in undergraduate college students. Journal of American College Health, 59(7), 596–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2010.515632

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Herda, D. N., & Martin, K. A. (2016). The effects of auditor experience and professional commitment on acceptance of underreporting time: A moderated mediation analysis. Current Issues in Auditing, 10(2), A14–A27. https://doi.org/10.2308/ciia-51479

Hystad, S. W., & Johnsen, B. H. (2020). The dimensionality of the 12-item general health questionnaire (GHQ-12): Comparisons of factor structures and invariance across samples and time. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1–11.

Jackson, C. (2007). The general health questionnaire. Occupational Medicine, 57, 79. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kql169

Jones, A., Norman, C., & Wier, B. (2010). Healthy lifestyle as a coping mechanism for role stress in public accounting. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 22, 21–41. https://doi.org/10.2308/bria.2010.22.1.21

Kelly, J., LaVergne, D., Boone, H., & Boone, D. (2012). Perceptions of college students on social factors that influence student matriculation. College Student Journal, 46(3), 653–664.

Kilfedder, C. J., Power, K. G., & Wells, T. J. (2001). Burnout in psychiatric nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 34(3), 383–396. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01769.x

Klussman, K., Curtin, N., Langer, J., & Nichols, A. L. (2020). Examining the effect of mindfulness on well-being: Self-connection as a mediator. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 14(5), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1017/prp.2019.29

Klussman, K., Lindeman, M. I. H., Nichols, A. L., & Langer, J. (2021). Fostering stress resilience among business students: The role of stress mindset and self-connection. Psychological Reports, 124(4), 1462–1480.