Abstract

The Directorate General for Competition at the European Commission enforces competition law in the areas of antitrust, merger control, and State aid. After providing a general presentation of the role of the Chief Competition Economist’s team, this article surveys some of the main developments at the Directorate General for Competition over 2019/2020. In particular, the article reviews the economic analysis in the Qualcomm predation case, recent developments in the assessment of vertical mergers, as well as the new “Temporary Framework” that has been developed in the wake of the COVID pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

This article provides an overview of the activity of the Directorate-General for Competition of the European Commission (DG Competition) in 2019/2020 in the areas of antitrust, mergers, and State aid (Sect. 1). In the following sections, the contribution by the Chief Economist Team (CET) to the economic analysis in specific cases is presented: Sect. 2 reviews the Qualcomm predation case; Sect. 3 discusses recent developments in the assessment of vertical mergers; and Sect. 4 presents the Temporary Framework that was adopted in order to deal with a surge in State intervention to alleviate the COVID-induced economic crisis.

1 Main Developments in 2019/2020

1.1 The Chief Competition Economist Team

The CET is a part of DG Competition. Its staff consists of around 30 economists (mostly holding a Ph.D.) with a mix of permanent and temporary positions. The CET is headed by the Chief Competition Economist, an external academic who is recruited for a 3‑year term. The current Chief Competition Economist is Pierre Régibeau, who succeeded Tommaso Valletti in 2019.

The CET has both a support role and a scrutiny role. As part of its support role, the team provides guidance on methodological issues of economics and econometrics in the application of EU competition rules. It contributes both to individual competition cases—in particular, those that involve complex economic issues and quantitative analysis—and to the development of general policy initiatives. It also assists with cases that are pending before the courts of the European Union.

Members of the CET who are assigned to specific cases have a specific and independent status within case teams and report directly to the Chief Competition Economist. As part of the scrutiny role, the Chief Competition Economist can report his opinion directly to the Director‑General of DG Competition as well as to the Competition Commissioner, providing her with an independent opinion with respect to the economic aspects of a case before she proposes a final decision to the European Commission.

The CET is active in DG Competition’s three main areas of policy: antitrust, merger control, and State aid.

1.2 DG Competition’s Activities in 2019/2020 Footnote 1

1.2.1 Antitrust

Between January 2019 and July 2020, the European Commission took decisions in 13 (non‑cartel) antitrust cases. Eight of these cases—involving Mastercard II, Google AdSense, Nike, Cross-border access to pay-TV, Mastercard and VISA Inter-regional MIF, AB InBev, and Character merchandise—are listed and briefly discussed in Kotzeva et al. (2019). The Qualcomm predation decision of July 2019 is reviewed in depth in Sect. 2 of this paper. The other four antitrust decisions adopted by the European Commission were: Broadcom of October 2019,Footnote 2 Film Merchandise—Universal of January 2020,Footnote 3 Meliá of February 2020,Footnote 4 and Romanian gas interconnectors of March 2020.Footnote 5

During the 2019–2020 period, the two most relevant ECJ rulings were UK GenericsFootnote 6 of January 2020 and Budapest Bank of April 2020.Footnote 7 Both cases were requests for a preliminary ruling: The first one was made by the Competition Appeal Tribunal; the second was made by the Hungarian Supreme Court.

In UK Generics, the Court held that settlement agreements whereby a manufacturer of generic medicines undertakes not to enter the market or challenge a patent in return for transfers of value have the object of restricting competition if it is clear that the net gain from the transfers of value can have no explanation other than the commercial interest of the parties not to engage in competition on the merits, and unless the settlement agreement is accompanied by proven pro-competitive effects that are capable of giving rise to a reasonable doubt that it causes a sufficient degree of harm to competition.

The ruling in Budapest Bank is particularly relevant to allegations of anticompetitive conduct in so-called “multi-sided” markets—e.g., payment systems, digital platforms, etc—where the interactions between related, but distinct markets must be taken into account by the competition authority. In its ruling, the ECJ held that Article 101(1) allows the same conduct/practice to be considered anticompetitive both by object and by effect, but which conduct harms competition "by object" must be interpreted restrictively: An agreement that determines the amount of the Multilateral Interchange Fees (MIFs) cannot be qualified as a restriction by object unless—in view of the content, objectives, and context of the agreement—it can be considered sufficiently harmful to competition. If an agreement appears to pursue both a legitimate and an anticompetitive objective, the legitimate objective may disqualify the agreement as being anticompetitive by object and warrant the assessment of its effects.

The period 2019–2020 was further characterized by intensive activity across numerous antitrust policy fields. In particular, the European Commission launched Public Consultations on: the Review of the Market Definition Notice; the Vertical Block Exemption Regulation (VBER); the Horizontal Block Exemption Regulation (HBER); the Motor Vehicle Block Exemption Regulation (MVBER); and the Consortia Block Exemption Regulation (CBER). Further Public Consultations were launched on the initiative of collective bargaining for the self-employed,Footnote 8 and on the Inception Impact Assessment of the New Competition Tool.Footnote 9

1.2.2 Mergers

Between January 2019 and August 2020, 600 merger investigations were concluded at DG Competition. The vast majority (453 cases) were unconditional clearances under a simplified procedure. 16 cases were abandoned in phase I. Of the remaining cases, 118 were concluded during a (non‑simplified) phase I investigation and 11 during a phase II investigation.Footnote 10 Of the (non‑simplified) phase I cases,Footnote 11 98 were cleared unconditionally, and 20 could be cleared in phase I subject to commitments. The phase II investigations resulted in one unconditional clearance,Footnote 12 seven clearances that were subject to commitments,Footnote 13 three prohibitions,Footnote 14 and two abandoned transactions.Footnote 15 Therefore, 8% of cases were not cleared unconditionally during this period.

The CET was involved in all second‑phase investigations as well as in many complex first‑phase investigations. Analyses by members of the CET included, for instance, merger simulations, bidding analyses, price pressure analyses, quantitative market delineation, as well as conceptual contributions to the construction and testing of sound theories of harm.

In terms of broader policy themes, there is an ongoing debate about the fine-tuning of merger control instruments to the specific challenges that are faced by today’s market environment: On the one hand, there have been calls for more flexible merger enforcement in the wake of Siemens/Alstom to permit the creation of European Champions. On the other hand, concerns have been raised about the increase in market power that has been observed in a significant number of industries.Footnote 16

In an important recent speech, Commissioner Vestager outlined the scope of the ongoing process of the evaluation of merger control.Footnote 17 She underlined the importance of effective merger control for European competitiveness and pointed to a number of initiatives aimed at optimizing its application in view of the current economic challenges. These include (among others) the following:

-

the acceptance of Member State referrals of mergers below the EU’s revenue thresholds with significant anti-competitive potential (e.g., potential “killer acquisitions” in pharmaceutical and digital markets);

-

material simplification of merger procedures to reduce the administrative burden for companies in situations where competitive concerns appear unlikely;

-

review and consultations on the substance of merger enforcement: e.g., through ex-post assessments of past enforcement and an open dialogue on current issues such as increased concentration and market power in digital markets.

In terms of court developments, the Commission faced a setback in the General Court’s recent CK Telecoms decision, which overturned the Commission’s prior prohibition decision in the UK mobile case Hutchison 3G UK/Telefónica UK.Footnote 18 In this judgment, the Court held that the Commission must meet a higher burden of proof in such cases than the balance of probabilities. Moreover, it found that, in horizontal mergers, the Commission must presume the existence of standard efficiencies that are said to flow from such transactions. The Commission has recently appealed the ruling to the European Court of Justice.

1.2.3 State Aid

Between January 2019 and July 2020, the Commission adopted 684 decisions in the area of state aid. Most of those decisions concluded that the actions were compatible with the Commission’s criteria for justifiable actions or did not actually involve aid.Footnote 19

During this period there has been significant policy work. The Commission launched in early 2019 an evaluation of State aid rules: a “fitness check.”Footnote 20 This is a process that reviews principally the rules under the State aid Modernisation package. This evaluation assesses whether the rules are fit for purpose and covers two regulations and nine guidelines, including: the General block exemption regulation Environmental and Energy guidelines; Risk Finance guidelines; and the Important projects of common European interest (IPCEI) guidelines. Also, the Commission has been revising the existing guidelines in the context of the greenhouse gas emission allowance trading scheme (ETS guidelines).

In addition, the COVID-19 outbreak has brought new challenges and the need for a flexible framework to channel State aid measures. A temporary framework (TF) was therefore adopted in March 2020 that addresses the serious economic disturbance caused by the pandemic while not jeopardising the level playing field in the internal market. A detailed analysis of the TF follows in Sect. 4 below. In June 2020, the Commission also adopted a White Paper that discusses the right tools to ensure that foreign subsidies do not distort the internal market.Footnote 21

In the area of banking, the Commission has authorised two recapitalisations: that of German Norddeutsche Landesbank—Girozentrale (NordLB)Footnote 22 and Romanian CEC Bank.Footnote 23 The Commission considered that the two transactions were in compliance with the market economy operator (investor) test since the expected remuneration of the State was considered to be in line with that expected by a private operator in similar circumstances. The Commission also authorised public support of EUR 3.2 billion for an IPCEI project for research and innovation in the common European priority area of batteries: a common project of seven Member States and 17 direct participants.Footnote 24 In the broadband market, the Commission authorised a number of schemes—including a Bavarian scheme for very high capacity broadband networks.Footnote 25

The CET has been closely involved in the TF work streams, and significant cases (e.g., the Lufthansa, SAS, German recapitalisation scheme). The CET has contributed to the design of the TF, and in case work notably analysing proportionality needs, the appropriate remuneration as well as governance conditions in various cases. The CET has worked extensively on the energy sector: on policy work and also on individual cases. A significant contribution has been on recapitalisation cases (such as the banking cases mentioned above) as well as funding gap analysis for IPCEIs and the infrastructure project of Fehmarn Belt.Footnote 26

2 Predatory Pricing in High Tech Industries: The Qualcomm Case

This section draws in large part on Scholz et al. (2020).

The Decision of 18 July 2019 on the Qualcomm (predation) caseFootnote 28 is the European Commission’s first predatory pricing case since the Wanadoo Decision of 2003.Footnote 29 It concerns the market for “baseband” chipsets of the third generation—Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (UMTS) chipsets—which are used in mobile devices (such as mobile phones, tablets, and “dongles”) to enable calls and data exchange via the cellular network.Footnote 30

The Commission concluded that between 1 July 2009 and 30 June 2011, Qualcomm abused its dominant position in the UMTS chipset market by selling certain volumes of three of its UMTS baseband chipsets to two of its key customers—Huawei and ZTE—below cost, with the intention of foreclosing Icera: its most important competitor in the leading-end segment at the time. For this infringement of Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (‘TFEU’), the Commission imposed a fine of EUR 242 million on Qualcomm. Qualcomm lodged an application for annulment of the Decision in November 2019, which is currently pending before the General Court.

2.1 Facts of the Case

During the investigated period, Qualcomm was the dominant developer and manufacturer of mobile communications technologies and baseband chipsets in a variety of standards—in particular, baseband chipsets that were based on UMTS. Qualcomm’s customers are device makers—original equipment manufacturers (OEMS)—that buy baseband chipsets and integrate them into their mobile devices before selling them to mobile network operators (MNOs) or wholesalers of electronic devices.

Icera—a semiconductor start-up that was founded in 2002 and was headquartered in Bristol (United Kingdom)——specialised in the development of UMTS baseband chipsets. In May 2011—towards the end of the period for which the Commission found predation—Icera was acquired by the US technology company Nvidia. In 2015, Nvidia decided to wind down its baseband chipset business, thus withdrawing the particular chipset technology that had been developed by Icera (so-called soft modems) from the market. This market exit led to a reduction in product variety and a possible slowdown in technological progress and therefore had a negative impact on consumers.

The Qualcomm case differs from previous European predatory pricing cases, such as the Wanadoo decision of 2003, mainly because almost all of the investigated prices were above average variable costs (AVC) but below long-run average incremental costs (LRAIC). By contrast, in the previous predation cases only part of the sales had been made at a price between AVC and LRAIC, whereas the price was below AVC for a significant volume of sales. In the Qualcomm predation case, the finding that Qualcomm’s conduct was intended to foreclose Icera from the market was therefore an essential element of the Decision that complemented the results of the price-cost test. This finding of intent is based on a thorough analysis of Qualcomm’s contemporaneous internal documents, which were supplemented by third-party information. The analysis of the documentary evidence gave a clear picture of the market environment around the period of the infringement and Qualcomm’s desire to defend its dominant position by means of an abusive predatory pricing strategy against Icera.

2.2 The Rationale of Qualcomm’s Conduct: Nipping Competitors in the Bud

While Qualcomm’s conduct during the investigated period aimed at protecting Qualcomm’s dominance in the entire UMTS chipset market—and in particular its strong position in the high-volume segment of baseband chipsets for use in mobile phones—its pricing strategy was selective: in terms of the market segment and also the customers that were affected by predatory prices.

First, Qualcomm’s strategy focused on UMTS chipsets that offered advanced data rate performance: the “leading-edge segment”. In this segment, Icera had started to gain traction in 2008/2009 due to: the software upgradability of its chipsets to leading-edge data rates; its smaller die size; and its competitive pricing.Footnote 31

Second, Qualcomm's strategy focused on Huawei and ZTE: the two strategically most important customers for leading-edge UMTS chipsets during the relevant period. These two customers were the main OEMs of “mobile broadband” (MBB) devices at the time.Footnote 32 While the market for MBB devices was (and still is) relatively small compared to the mobile phone market, they were particularly important for the leading-edge chipsets that were supplied by Icera and Qualcomm.

By containing Icera’s growth at the two key customers in the leading-edge segment, which consisted at the time almost exclusively of chipsets that were used in MBB devices, Qualcomm intended to prevent Icera—a small and financially constrained start-up—from gaining the reputation and scale necessary to challenge Qualcomm’s dominance in the wider UMTS chipset market. Qualcomm was particularly concerned by Icera’s threat because of the expected growth potential of the leading-edge segment due to the global take-up of smart mobile devices.

Thus, while only a small part of the UMTS chipset market was affected by below-cost pricing, this selective and targeted predatory strategy had an adverse impact on the entirety of the market that the strategy intended to foreclose. Moreover, Qualcomm’s conduct also affected the contestability of future markets, beyond the UMTS chipset market on which the predatory attacks occurred. With revenues from MBB sales falling below Icera’s targets, Icera was forced to scale back its R&D in voice functionality/LTE, which was crucial for Icera to be able to enter the LTE smartphone segment as scheduled by the end of 2011. Instead, Icera’s entry into the LTE smartphone segment was delayed to February 2013, by which time Icera had already lost the commercial opportunity of being the first entrant in this segment; and its acquirer, Nvidia, eventually wound down Icera’s modem operations in May 2015.

2.3 Economic Analysis of Predatory Pricing: Principles

Predatory pricing cases are notoriously difficult to pursue, which may explain why they are “something between a white tiger and a unicorn”.Footnote 33 At a conceptual level, economists have long struggled to come up with a convincing rationalisation of below-cost pricing that lives up to the standards of modern game theory.Footnote 34 The idea that predation may involve a dynamic strategy where market entrants can at first only compete on a sub-segment of the market, which may become the theatre of a predatory attack to protect future markets, has only recently been explored.Footnote 35

At an operational level, the difficulty of establishing predatory pricing lies in the fact that “low” prices can arise both under predation and under a pro-competitive reaction to entry, with prices “naturally” declining as the competitive pressure experienced by the incumbent increases. In technical terms, this inherent ambiguity may lead to two types of errors: A Type I error consists in failing to identify a predatory attack when in fact it has occurred. If such a Type I error is likely to occur, this weakens antitrust enforcement and encourages unlawful behaviour. A Type II error consists in finding predation when in fact there was none. The problem with Type II errors is that they tend to have a chilling effect on competition, as incumbents may hesitate to react pro-competitively to entry for fear of triggering an antitrust investigation.

Different jurisdictions have tried to solve this conundrum in different ways. In the US, the legal standard for finding predatory pricing is based on the “Areeda-Turner” test, which requires that prices are below short-run AVC, and that recoupment is at least possible.Footnote 36

The legal framework applicable in the EEA builds on two different tests, known as the AKZO I and AKZO II tests. With respect to the relevant cost benchmark, the case law states that “first, […] prices below average variable costs must be considered prima facie abusive inasmuch as, in applying such prices, an undertaking in a dominant position is presumed to pursue no other economic objective save that of eliminating its competitors. Secondly, prices below average total costs but above average variable costs are to be considered abusive only where they are fixed in the context of a plan having the purpose of eliminating a competitor.”Footnote 37

In other words, there is a presumption that prices below AVC are abusive (AKZO I). However, even prices above AVC (but below average total costs) may be found abusive, provided that there was exclusionary intent (AKZO II). The Qualcomm predation case discussed in this article falls squarely within this second category. While prices above AVC do not generally give rise to antitrust concern (as they are compatible with many forms of pro-competitive behaviour), they are not a safe haven in the EEA, as the existence of evidence on intent may give rise to a finding of abusive pricing nonetheless.

2.4 Economic Analysis of Predatory Pricing: The Qualcomm Case

As explained above, Qualcomm’s predatory pricing strategy was targeted at certain products and customers, which were indispensable for Icera’s development prospects on the UMTS market and beyond, but represented only a small part of Qualcomm’s product portfolio or turnover. The Commission therefore focused its price-cost test on those three chipsets and the two customers on which Qualcomm’s predatory pricing strategy was based. The test was carried out in three steps, which are explained in more detail below: (1) the reconstruction of the effectively paid prices; (2) the comparison of these prices with Qualcomm’s AVC; and (3) the calculation of the non-variable production costs and the comparison of the prices with Qualcomm’s LRAIC.

For reasons of legal certainty, the relevant cost benchmark for both the AVC and non-variable costs included in the calculation of LRAIC were the costs of the dominant undertaking (i.e., Qualcomm), not the costs of the foreclosed undertaking (i.e., Icera), as the latter would not normally be known with the necessary degree of precision to the dominant undertaking. Therefore, the Commission’s price-cost test is equivalent to an “as-efficient-competitor” test: It indicates whether—under the assumption that Icera was as efficient as Qualcomm in producing the products under investigation—Icera could have survived in the market in the long run in the face of the prices that were charged by Qualcomm.Footnote 38

2.4.1 From Accounting Prices to Effectively Paid Prices

In the Statement of Objections of December 2015, the Commission had used Qualcomm’s average prices from its formal accounting in its price-cost test. However, these data only partially reflected the unit prices that were effectively paid by Huawei and ZTE for the products that were under investigation. In addition to the realised revenues from the quantities that were sold at any given time, the accounting prices also included the release of reserves that had been created to cover possible (eventually non-realised) rebate claims for units that were shipped in previous quarters, which were therefore unrelated to the units that were shipped in the quarter in which the release was recorded. Following an in-depth analysis of the resulting distortions, the Commission considered that it was necessary to correct the accounting price data for these releases by allocating them to the sales to which they effectively related.

Furthermore, the Commission’s investigation revealed two one-off payments that were made by Qualcomm to Huawei and ZTE, respectively. In Qualcomm’s accounts, these one-off payments had been attributed to a specific chipset model. However, it was apparent from internal Qualcomm documents (sometimes supported by third-party documents) that these one-off payments were intended as a discount for certain quantities of other chipsets for which Qualcomm did not wish to reduce the price directly at that time. The Commission therefore allocated the one-off payments in question to the specific sales that resulted from those documents, which significantly reduced the unit price effectively paid for the sales in question.

The effectively paid prices thus established were then cross-checked against relevant internal documents that reflected Qualcomm’s plan to foreclose Icera from the UMTS chipset market. The price reconstruction carried out by the Commission made it possible to link each of the price points discussed in those documents to the actual transactions that had occurred at these prices. In doing so, the Commission provided the necessary proof that the predatory pricing strategy that was envisaged in the Qualcomm documents had actually been implemented.

2.4.2 Comparison of Prices and Variable Costs

Since Qualcomm does not manufacture its chips itself, but outsources this to third-party chip manufacturers (“foundries”), the AVC was calculated on the basis of the unit prices that were invoiced by Qualcomm’s foundries for the shipments of the respective chipsets to Qualcomm. In order to take account of the fact that not all chipsets were immediately resold but sometimes kept in stock for some time, the Commission reconstructed the respective stocks so as to allow for a meaningful comparison of the acquisition cost of any given chipset to the price that was charged for this chipset by Qualcomm in the quarter in which it was eventually sold.

As mentioned above, the unit prices effectively paid by Huawei and ZTE were always above the AVC calculated by the Commission, with very few exceptions. The legal standard to be applied is therefore the AKZO II standard: There may also be abusive pricing at levels that are between AVC and average total cost (ATC) if these prices were intended to foreclose a competitor from the market.

2.4.3 Comparison of Prices and LRAIC

As in previous cases (see, for example, Wanadoo), the Commission considered LRAIC—the average of all (variable and fixed) costs that were incurred by Qualcomm in the production of the products under investigation—to be the most appropriate cost measure for the purposes of the price-cost test. LRAIC is below ATC because Qualcomm is a company that produces a large number of different products, of which only three specific chipset models were relevant for the implementation of its predatory pricing strategy vis-à-vis Icera. In the case of a multi-product company, in addition to the costs that can be attributed to the production of certain products, there are also genuine “common costs” (such as commercialisation or administrative costs) that could not have been avoided if a single product had not been produced. Such common costs are therefore not taken into account in the calculation of LRAIC, but would be fully included in the calculation of ATC. LRAIC is therefore a conservative cost benchmark as compared to ATC.

In order to calculate LRAIC for the investigated chipsets, the Commission relied, in addition to the AVC, on product-specific development costs that were obtained from internal Qualcomm documents. The latter costs do not vary with the short-run volume of sales (and are therefore not part of variable costs), but are unavoidable in the long run to achieve the entirety of the chipset sales under investigation. As most of these development costs are incurred before the sale of the chipsets to which they relate, the Commission had to allocate these development costs to the investigated chipset sales, with the use of a revenue-based allocation method. This approach takes into account the fact that leading-edge chipsets tend to generate the highest margins at the beginning of their product life cycle, since the innovative added value of these products is highest when they are first launched on the market.

In this context, if instead a quantity-based allocation were to be applied—as is common in business cost accounting—this would significantly increase the LRAIC for the products under investigation towards the end of their life cycle, when the sales volumes are still high, but margins tend to be much lower. As a result, costs would mechanically exceed prices in later periods, even though no predatory pricing may have been intended.

For innovative products whose margins are subject to such strong variations over the life cycle, a revenue-based allocation takes account of the impact of these life cycle dynamics on the calculated minimum margin in a realistic manner. This approach also allowed the Commission to take into account spill-over effects between two of the three products under investigation.

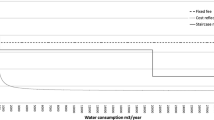

The Commission then compared the effectively paid prices with the respective LRAIC. This comparison was carried out on a quarterly basis for each of the three investigated chipset models and for each of the two key customers. The test showed that almost all sales to Huawei and most of the sales to ZTE were made at prices that were below the respective LRAIC. Qualcomm’s total revenue from these predatory sales was well above Icera’s total turnover in 2011 (the last year in the investigation period).

At the beginning of the period under investigation, Icera had already established a nascent sales relationship with ZTE, and so Qualcomm’s strategy focussed mainly on Huawei: By selling at below-cost prices to Huawei, the latter was to gain a competitive advantage at the next level of the supply chain where chipset suppliers such as Qualcomm and Icera compete indirectly for orders of MNOs through the MBB devices of OEMs that incorporate their respective chipsets. Only later did Qualcomm extend its predatory strategy also to ZTE.

The established case law does not require the Commission to prove recoupment after a predatory episode. In the Qualcomm case, however, it was apparent from the dominant undertaking’s internal documents that such recoupment was never envisaged, and would not have been possible, over the remaining life cycle of the investigated products. This is because (as was described above) the margins of chipsets in the leading-edge segment tend to fall rapidly after a short period of time, even absent any predatory pricing strategy. Instead, the “payoff” from Qualcomm’s strategy was that Icera was prevented from entering the much larger and more profitable segment of smartphone chipsets, which would have resulted in a much more significant loss of profits for Qualcomm than that caused by the predatory pricing episodes on the smaller segment of MBB devices.

Yet, in addition to the price-cost test that was described above, the Commission also examined whether the two high-volume chipsets under investigation had eventually recovered their aggregated LRAIC when their total life-cycle revenues are considered. The main differences with the above-mentioned price-cost test were as follows: (1) The Commission took into account the whole life cycle revenues of the products, including sales in the period following the infringement period (when one of the two high-volume products was still on sale); (2) the Commission also took into account all of the revenues that were obtained from other customers of these two products (not only Huawei and ZTE); and (3) the Commission carried out the test not only for each chipset, but also at the level of the chipset family: The Commission pooled the revenues and the development costs of the two products. Thus, although this overall life cycle analysis took into account far higher revenues than the above price-cost test, the investigation showed that—even at the product-family level—the two products did not fully recover their aggregate product-specific production costs (including development costs). This result does not depend on the specific assumptions that were made about the allocation of development costs and thus corroborates the result of the price-cost test in this case.

3 Conclusions

The sparse case law on predatory pricing cases—both in the EU and outside (e.g., in the US)—shows that such cases are usually characterised by high complexity, which often makes it much more difficult to pursue such forms of abusive pricing than other types of anti-competitive pricing practices. This is all the more the case where the industry under investigation is characterised by high fixed costs and relatively low variable costs, so that a price-cost test that is based exclusively on variable costs may not allow the identification of the existence of predatory prices in all cases.

The Qualcomm decision shows that—even in such inherently complex cases—the Commission strives to enforce rigorously the relevant competition rules so as to: tackle anticompetitive conduct; deter future abusive conduct; and, where possible, restore effective competition in the affected markets.

As announced by Qualcomm on the day of the adoption of the Qualcomm predation Decision, Qualcomm lodged an application for annulment of the Decision.Footnote 39 Qualcomm’s appeal is mainly based on the following claims: (1) a lack of perceived competitive threat from Icera, since customers turned to Qualcomm’s products not because of their price but because rival chipsets were (according to Qualcomm) technologically inferior, (2) a lack of precedent and economic rationale for the Decision’s theory of harm, which is based on alleged below-cost pricing over a very short time period and for a very small volume of chips (see Sect. 2.2 above on the Commission’s view of this rationale), and (2) a lack of anticompetitive harm to Icera from Qualcomm’s conduct, given that Icera was later acquired by Nvidia and continued to compete in the relevant market for several years after the end of the alleged conduct (see Sect. 2.2 above on the Commission’s view of the course of events). The appeal is currently awaiting judgment by the General Court.

4 Recent Developments in the Assessment of Vertical Mergers

This section is in large part based on Zenger (2020).

In the context of AT&T/Time Warner and the recent publication of U.S. Vertical Merger Guidelines, vertical mergers have become a topic of intense debate again.Footnote 41 Against this background, this section describes the recent developments in the application of economic analysis in vertical mergers at the Commission.

Section 3.1 discusses the Commission’s general approach toward analyzing vertical mergers. Section 3.2 describes classes of cases where anti-competitive incentives for raising rivals’ cost (RRC) are likely to dominate pro-competitive incentives for the elimination of double marginalization (EDM). Finally, Sect. 3.3 analyzes two specific mergers of this type in more detail, which the Commission assessed in the previous year.

4.1 Measuring Economic Effects in Vertical Mergers

4.1.1 Ability-Incentive-Effect

The basic economic principles of assessing vertical mergers are set out in the Commission’s Non-Horizontal Merger Guidelines.Footnote 42 Specifically, the Commission applies a three-prong test, which analyzes: (1) whether the merged entity has the ability to foreclose rivals; (2) whether the merged entity has an incentive to foreclose rivals; and (3) whether such foreclosure would lead to competitive harm in the downstream market.Footnote 43

From an economic perspective, the ability to foreclose requires that the input in question is a critical input: (1) that it is important for downstream competition and (2) that the merged entity has substantial market power over it. An incentive to foreclose requires: (1) that lack of access to the input would cause significant diversion from a foreclosed rival to the merged downstream business; and (2) that such diverted sales would be profitable for the merged entity.

Contrary to horizontal cases, measuring diversion ratios can be appreciably more involved in vertical cases. Indeed, in vertical cases a price increase for a critical input may not only cause diversion in the downstream market, but may also lead to switching in the upstream (input) market. When such input substitution is plausible, the diversion ratio to the merged entity’s downstream business may therefore be significantly diluted. In practice, measuring the likelihood and magnitude of this effect is not always straightforward.

In some instances, firms’ internal documents contain estimates of likely departure rates in the event of a loss of access to the input. In other instances, there may be empirical evidence from past price changes in the market.Footnote 44 However, such direct evidence is not always available. In its absence, the size of profit margins can be useful as an indicator for the relative importance of upstream and downstream substitution. For example, when upstream margins are large, whereas downstream margins are small, then this indicates that downstream demand is elastic whereas upstream demand is not. In that situation, it will be much easier for customers to switch the downstream product than the upstream product.

Finally, the third prong of the test requires that harm to competition and consumers is shown—not merely harm to competitors. This implies: (1) that the merged entity does not face significant competition from rivals that are not subject to foreclosure (e.g., other vertically integrated firms); and (2) that the upward pricing pressure (UPP) that is created by RRC is not completely offset by EDM or other efficiencies.

4.1.2 Interaction of EDM and RRC

Recent literature has correctly pointed out that the price-increasing effect of RRC and the price-reducing effect of EDM are not fully separable effects, but influence each other.Footnote 45 From an economic perspective, both RRC and EDM result from the same post-merger profit optimization. While the upstream firm’s desire to benefit its downstream partner generates incentives for RRC, the downstream firm’s desire to benefit its upstream partner generates incentives for EDM. Consequently, the equilibrium values of RRC and EDM are interrelated.

This is not simply a matter of “weighing the EDM efficiency against the RRC harm.” When EDM is sufficiently large, then it reduces the very (equilibrium) incentive to engage in RRC. This follows because recaptured sales are less profitable for the merged entity when EDM has reduced downstream prices. As the above-noted papers show, this feedback effect can be so strong that the merged entity decreases not only its downstream prices in equilibrium but even decreases the upstream prices it charges to third parties. There is therefore no trade-off between EDM and RRC anymore, and all consumers benefit from the transaction.

One should be careful not to over-interpret this result, however. For example, it is based on models that assume an extreme form of pre-merger double marginalization. Concretely, all of the above papers assume that pre-merger mark-ups are so large that prices exceed the level that even an integrated monopolist would set. It is therefore not surprising that vertical integration leads to strong EDM in these models, as this permits the merged entity to reduce prices toward monopoly levels.

Indeed, in less extreme situations, the reverse result equally applies: If EDM is sufficiently small, then RRC may not only increase the upstream price charged to rivals but the integrated firm will also raise its downstream price. Hence, there is again no trade-off between EDM and RRC but instead all consumers are harmed by vertical integration.Footnote 46

4.1.3 Use of Economic Models

In order to assess the often-complex economic effects of vertical integration, the Commission has sometimes used economic models in its competitive assessment. Models that have been considered in recent case practice among others include: vertical arithmetic (VA); bargaining models; vertical gross upward pricing pressure indices (vGUPPIs); and merger simulation.

VA is the simplest form of quantitative analysis and is often submitted to the Commission by merging parties. It assesses the merged entity’s incentives for total foreclosure based on: (1) firms’ pre-merger margins; and (2) the expected diversion ratio from third parties to the merged entity’s downstream unit in the event of a loss of access to the critical input.

VA is straightforward to apply. But unfortunately, it also has significant limitations: First, it will typically be more profitable for the merged entity to raise the price of the input instead of engaging in an outright refusal to supply. Second, even if the merged entity refuses to supply the input, post-merger prices will typically change as a result of the transaction (e.g., due to EDM). For this reason, VA can provide only indicative evidence about likely foreclosure incentives.Footnote 47

More advanced models that also permit assessing the merged entity’s pricing incentives are the bargaining leverage model (for markets with negotiated prices) and vGUPPI analysis (for markets with posted prices).Footnote 48 These models operate in a similar fashion as price pressure models in horizontal cases.Footnote 49 They can be highly instructive to identify the core parameters that drive pricing incentives. Moreover, they permit quantifying the upward pricing pressure that may result from vertical integration.

The vGUPPI model also allows for a direct quantification of countervailing EDM incentives. Similarly, Shapiro (2018) illustrates how EDM incentives can be measured in the bargaining context. However, both approaches abstract from the feedback effects between EDM and RRC (as discussed in Sect. 3.1.1). This is because they are partial equilibrium models that calibrate pro—and anti-competitive effects separately, rather than jointly.

A complete balancing of pro—and anti-competitive effects—including feedback effects—in principle requires a full merger simulation. Such vertical models exist and have been applied, in particular in academic contexts.Footnote 50 However, such vertical simulations tend to be relatively complex due to the intricate interaction of upstream and downstream markets. As a result, they can be sensitive to seemingly innocuous parameter assumptions—e.g., as to demand curvature—that may be difficult to verify in merger proceedings. Therefore, their use in antitrust practice has so far been limited.

4.2 Classes of Cases Where Anti-competitive Effects are Likely to Dominate

As the previous section has illustrated, a full balancing of EDM and RRC including feedback effects can be complex in vertical mergers. While economic models can help with such assessments, evidence for foreclosure is likely to be particularly robust when EDM is expected to be small (or absent). This section therefore portrays different classes of vertical mergers where EDM is likely to be of limited relevance. These classes are based on recent Commission case experience (we discuss two such cases in more detail in Sect. 3.3 below).

4.2.1 Diagonal Mergers

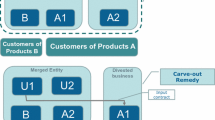

An important reason why RRC may significantly outweigh EDM can be that rivals rely on the critical input more often than the merging firm itself does. For example, in Deutsche Börse/LSEG, Deutsche Börse proposed to acquire a clearing house that was an essential input for competing stock exchanges.Footnote 51 Deutsche Börse itself, however, was already vertically integrated into clearing services. Hence, the transaction did not present any scope for EDM in this market. However, control of the clearing house would have permitted Deutsche Börse to increase materially the costs of its rivals.Footnote 52

As this case illustrates, diagonal mergers can lead to straightforward competition concerns without the need to engage in a complex balancing exercise. In the example of Deutsche Börse/LSEG, RRC incentives were substantial, and there was simply no scope for countervailing EDM.

4.2.2 Full Market Coverage

A second class of cases with limited scope for EDM are situations where the critical input already has close to full market coverage. This was the case, for instance, in Telia/Bonnier Broadcasting (which will be discussed in more detail in Sect. 3.3.1 below).Footnote 53 In that case, the critical inputs were TV channels, to which the vast majority of potential viewers already had access pre-transaction. In such situations, the downstream firm cannot meaningfully expand demand for its upstream partner by reducing its price (at least as far as winning new customers is concerned). Instead, price reductions would merely cannibalize upstream sales that would otherwise have been made via other distributors. Accordingly, EDM incentives are likely to be limited in such cases.

4.2.3 Contractual Reasons for Lack of EDM

EDM is also likely to be small if the merging parties already have contractual arrangements in place that allow double marginalization to be overcome pre-merger. This was the case, for instance, in Wieland/Aurubis (which will be discussed in more detail in Sect. 3.3.2 below).Footnote 54 In that case, the merging firms had a joint venture in place that already ensured that the input would be transferred to them at cost.

More generally, contractual solutions to avoid double marginalization include two-part tariffs and rebate schemes that ensure marginal cost pricing for incremental units. Note, however, that such contractual solutions may equally undermine incentives to engage in RRC.Footnote 55 Arguing that EDM is not merger-specific therefore requires an asymmetry in the contractual set-ups that relate to the merging downstream firm and independent competitors.Footnote 56

4.2.4 Horizontal Concerns That Undermine EDM

Finally, EDM is also unlikely to arise in vertical mergers when there is a significant horizontal overlap in the downstream market.Footnote 57 To see this, note that EDM is caused by the downstream firm’s desire to expand sales for its upstream partner. However, when there is also significant upward pricing pressure due to a horizontal overlap, then this will tend to dilute or overturn the incentive to reduce downstream prices.Footnote 58

4.3 Recent Vertical Merger Enforcement at the European Commission

Finally, we present in more detail two important vertical mergers of the last year, which illustrate many of the concepts discussed in this section: Telia/Bonnier Broadcasting and Wieland/Aurubis. The former case was cleared subject to significant access remedies (including FRAND licensing terms), whereas the latter case was ultimately blocked.

4.3.1 Telia/Bonnier Broadcasting

This case concerned the takeover of the leading private TV broadcaster in Sweden (Bonnier Broadcasting) by the leading Swedish telecoms operator that is also active in TV distribution (Telia). Specifically, Bonnier owned both the most important commercial free-to-air channel (TV 4) as well as leading premium TV channels with significant exclusive content (C More). The Commission’s main concern in this case was that the merged entity would significantly increase the licensing fees for Bonnier Broadcasting’s “must have” TV channels and thereby raise the distribution costs of Telia’s downstream rivals.

As noted in Sect. 3.2.2, Bonnier Broadcasting’s content was so ubiquitous in the affected geographic markets that the scope for EDM appeared modest at best. Conversely, the merged entity’s RRC incentives were likely to be significant, since a potential blackout of Bonnier Broadcasting’s TV channels was expected to cause significant switching of viewers away from foreclosed rivals.

In order to quantify the possible impact of increased bargaining leverage, the Commission used a calibrated bargaining model, which predicted a substantial post-merger increase in licensing fees. In applying this model, the Commission was able to rely on empirical estimates of the likely switching rates that would result from a potential blackout. These estimates were based on: (1) the parties’ own internal estimates of likely customer switching after a blackout, and (2) measured departure rates following a contemporaneous natural experiment, since Telia had recently made the distribution of some premium sports content exclusive on its network.

As was mentioned above, this case was cleared subject to significant access remedies.

4.3.2 Wieland/Aurubis

Wieland/Aurubis concerned the proposed merger of two copper producers with both vertical and horizontal links. Concretely, Wieland set out to acquire Aurubis’s downstream rolled copper operations, which led to standard horizontal overlaps. Moreover, Wieland planned to take sole control of Schwermetall, an upstream joint venture with Aurubis that provided pre-rolled strip (an input) to both firms and also to downstream competitors.

The pre-merger joint venture allowed both Wieland and Aurubis to obtain pre-rolled strip at preferential conditions to avoid double marginalization. Third-party rivals were instead charged profit-maximizing prices. In other words, the transaction did not generate significant scope for EDM. On the contrary, the transaction was likely to raise downstream prices due to the significant horizontal overlap between Wieland and Aurubis in rolled copper production.

In addition, the proposed merger was likely to generate strong incentives to raise the upstream prices for pre-rolled strip toward Wieland’s competitors. Pre-merger, Schwermetall had maintained operational independence from its parent companies with respect to third-party sales. This independence would cease after the transaction. Schwermetall was therefore likely to increase its prices, as this would benefit Wieland in the downstream market for rolled copper.

Since Wieland was not willing to address these concerns comprehensively, the transaction was ultimately blocked.

5 Recent Developments in State Aid Control

5.1 State Aid Temporary Framework: Flexible Rules at Crisis Times

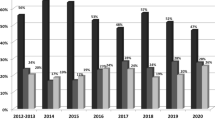

As of September 3, 2020, in the aftermath of the COVID outbreak, the European Commission had approved more than 317 national state support measures in more than 280 decision with a total estimated budget of close to EUR 3 trillion in COVID-related measures alone.Footnote 59 We first outline the main economic challenges of the crisis, and how the European Union has reacted so far, before focusing on the State aid temporary framework (TF) that has been adopted by the European Commission to address the need for support of the EU economy. While the TF preserves principles of State id, it also sets out more flexible rules to respond to the economic challenges that have been raised by the COVID outbreak.

5.2 COVID Crisis

The COVID pandemic’s impact on health, society, and the economy is unprecedented in the history of the EU. Those effects are linked as the current economic crisis stems mostly from the changes in consumer behaviour that have been triggered both by the public’s fear of contagion and by the public health measures that are aimed at containing the outbreak. The summer EU forecast foresees that the EU economy will contract by 8.3% in 2020.Footnote 60

The crisis is a mix of both supply and demand shocks. On the supply side, there have been disruptions in supply chains—including disruptions of transport networks when travel is severely restricted. Today’s economy includes many interconnected parties, and a sudden break in some part of these chains can easily lead to cascading effects.Footnote 61

On the demand side, consumers purchase both less and differently, which leads not only to a decrease in aggregate demand but also to very large drops in some sectors and insufficient capacity in others. There is also considerable uncertainty about the future: When will the health crisis be resolved? Will there be long-term effects on the pattern of demand and on the organisation of production? Decreased demand and uncertainty lead to higher borrowing costs—especially for risky sectors of the economy—thereby exposing the financial vulnerabilities of firms and households. To this already grim picture one must add the possible accumulation of non-performing loans in financial institutions, which might eventually endanger the stability of the financial system.

5.3 Policy Response

A fundamental goal of policymakers is to ensure that the negative shock from the new economic reality is short lived and that the economic linkages can be restored promptly: ensure that workers keep their jobs; viable firms do not go bankrupt; and banks can still provide lending.

On the monetary side, central banks have provided emergency liquidity to the financial sector. Long-term financing operations and targeted longer-term refinancing operations as well as asset purchase programme have been implemented by the ECB.Footnote 62,Footnote 63

On the fiscal side, the main policy response has been a mix of loans and grants (cash transfer, wage subsidies, tax relief) from the State to households and firms to help weather the liquidity challenges. This liquidity support is often granted at (very) preferential terms. Contrary to the last financial crisis, where financial institutions engaged in excessive risk taking, moral hazard is not a primary concern. Because the current crisis is unexpected and outside the control of firms and households, many feel that it calls for weak conditionality for the support that is provided.

But the crisis is not only about liquidity. The longer it lasts, the more it affects the earning and equity base of the companies. This calls for a recapitalisation framework, as with banks during the financial crisis, which would ensure the viability and survival of firms and jobs but also guarantee that taxpayers get a reasonable deal. The State would get shares or a return for the funds that it provides; hence the State could also have an upside potential for the solvency support it provides.

The EU response has been built mainly on the following pillars:

-

1.

Flexibility to allow Member States (MSs) to use their own resources to address the impact of the crisis. This has been achieved by:

-

a.

Adapting State aid rules to address economic disturbances from the COVID outbreak through the introduction of the TF. At a time of serious disturbance for the real economy it is crucial to establish flexible rules to ensure that funding can go where it is needed, under a common framework across MSs that thereby maintain a level playing field.

-

b.

Using the escape clause for the Stability and Growth Pact: The European Commission temporarily waived the budgetary rules so that MSs could exceed the limits that are imposed by the Pact.Footnote 64

-

a.

-

2.

Agreement on EU resources to help MSs address crisis needs. Although borrowing levels of EU sovereigns remain at historical lows, there are substantial discrepancies in “firepower” across Member States. This is reflected in the estimated budget of COVID-19 related approved schemes. For example, more than 50% of the State aid that have been approved so far has been notified by Germany.Footnote 65 The use of common EU resources is aimed at to alleviating such asymmetries. The Next Generation EU—the COVID-19 recovery package agreement of July 2020—includes EUR 390bn in terms of grants and EUR 360bn in loans to MS through the EU budget. The plan also envisages possible new resources and authorises the European Commission to borrow in the capital markets on the EU’s behalf and therefore mutualises part of the COVID response.Footnote 66 There are still discussions on the exact conditionality framework. The arguments against risk mutualisation and weak conditionality focus on the moral hazard argument. Similarly to the case of firms and households, some economists have made the argument of limited moral hazard associated with this crisis that could apply to MSs.Footnote 67

5.4 The Temporary Framework

The objective of State aid policy is to ensure a level playing field in the Internal Market where firms should compete on the merits rather than on the back of State support. The rationale is to avoid the emergence of “subsidy races” between Member States.

In the EU State aid architecture, national measures that constitute State aidFootnote 68 are not allowed unless there is a “compatibility basis”. To tackle the consequences of the crisis there are two principal compatibility legal grounds: The first is on the basis of Article 107(2) (b) TFEU, whereby Member States may compensate undertakings for damage that is directly caused by the COVID-19 outbreak. However, the scope of this article is narrow. In particular, the damage should be directly caused by public health measures that preclude the recipient of the aid from carrying out its economic activity.Footnote 69 Economic impact that results from the COVID-induced economic crisis does not qualify under this article.

Aid that addresses the economic downturn from the COVID-19 outbreak is to be assessed under the different compatibility basis of Article 107(3) (b) TFEU, which allows support to remedy the broader economic disturbance that is brought about by the outbreak under a set of conditions that are set out by the European Commission. On 19 March 2020, only a few days after the outbreak of the crisis in Europe, the Commission adopted the TF that outlined the basic requirements for compatible State aid in these exceptional economic circumstances.Footnote 70 This framework has already been amended three times on 3 April 2020, on 8 May 2020, and on 29 June 2020.,Footnote 71,Footnote 72

5.4.1 Description of Main Elements of the TF

The aim of the framework is to address the liquidity and solvency needs of otherwise healthy undertakings due to the negative economic impact of the COVID-19 outbreak. This framework is only relevant for companies that operate in the real economy – and thus excludes financial institutions.Footnote 73

Importantly, the core principles of the TF are also consistent with the overall State aid architecture. In this sense, the TF is better thought of as an application of the standard State aid approach to specific circumstances than to a change in the standards of State aid policy. These core principles are:

-

1.

More lenient treatment of small- and medium-size enterprises (SMEs), as compared to large enterprises. Distortions of competition are likely to be greater when State support is channelled to large enterprises since they are more likely to compete across the EU and significantly affect trade. Also smaller companies, ceteris paribus, are more likely to be affected by the crisis since they are likely to have greater difficulties to secure sufficient financing from the capital markets. Therefore the conditions for large enterprises are typically more stringent than for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) with higher remuneration for the State required in exchange for the support provided.

-

2.

Only otherwise viable undertakings are eligible for support. Therefore, firms that were in financial difficulties before the crisis should not receive aid under the TF. This is to avoid channelling funds to inefficient firms, or firms that would have had to undergo a restructuring process even in the absence of the COVID-19 outbreak. There are other avenues for such firms to receive State support: They could receive damages under 107(2) (b) TFEU (see above), or under the traditional “rescue and restructuring” aid under the relevant guidelines. The latter option having more stringent conditions compared to the TF.Footnote 74,Footnote 75

-

3.

The level of remuneration for the State is not directly linked to the creditworthiness of the undertaking. This is because the aid provided is not targeted to provide funds to finance the companies’ normal course of business and expansion plans but instead to weather a crisis that is beyond what companies could easily forecast in their normal course of business.

-

4.

No aid should be conditional on the relocation of the beneficiary’s activities from one EEA country to another. This is at the core of State aid control: to ensure that State measures do not lead to a race to the bottom to attract companies in their own territories.Footnote 76

-

5.

Detailed transparency and monitoring rules are set out to ensure that information can be publicly available.Footnote 77

In what follows we focus on two main sets of measures: liquidity support, and solvency support.Footnote 78

5.4.2 Liquidity Support Instruments

The liquidity measures that are envisaged in the TF must be granted before December 2020.

There are four main measures:

-

EUR 800,000 per company, in the form of grants or loans, can be given with no further conditions (no remuneration for the State and no need to demonstrate the liquidity problems of the beneficiary).Footnote 79 The rationale of this measure is that for a relatively small level of support, and in light of the scale of the crisis, there can be a presumption of no significant impact on the internal market. The burden for ensuring reasonable and effective use of funds falls fully on MSs. This type of support can only be part of a scheme—not individual companies alone.

-

Guarantees on loans: Companies can benefit from significant liquidity support, either in the form of State guarantees (so that they can raise funding from financial institutions at reasonable cost) or through direct State financing.Footnote 80 These two types of liquidity support can be combined but not cumulated: The loans that are received through either measure cannot jointly exceed the limits that are set out.

-

These repayable instruments can be granted at attractive rates. As shown in the table below, the guarantee fees start at extremely low rates (0.25% during the first year for SMEs). The rationale for the low rates was that, for instruments that are repayable, the distortive effect in the Internal Market would not outweigh the challenges that have been brought forward by the COVID-19 crisis and the common interest to intervene. Even if remuneration is low, there is a minimum remuneration to ensure that firms do not take up these loans simply because it is an option that is available to them. Moreover, the fees are increasing over time to provide incentives for early repayment.Footnote 81

Type of recipient | For 1st year | For 2nd-3nd years | For 4th-6th years |

|---|---|---|---|

SMEs | 25 bps | 50 bps | 100 bps |

Large enterprises | 50 bps | 100 bps | 200 bps |

The TF allows a maximum guarantee coverage of 90%.Footnote 82 This implies that the financial institution that grants the loan should also have some “skin in the game” in order to limit moral hazard on their part. The maturity of the loans can be up to 6 years. Finally, there are upper limits to the amount of loans that companies can raise with the State guarantee: a proportionality test. These limits are company-specific since they are determined as a function of the annual wage bill, the turnover, or the liquidity needs of the beneficiary.

Subsidised loans essentially refers to senior loans that are granted by a State—or by State-owned entities such as State-owned banks—at favourable rates. The credit spread on these loans can be as low as the guarantee fees that were set out above.Footnote 83

-

The second amendment of the TF extends the set of allowable tools to subordinated debt. Because subordinated debt is junior to normal (senior) loans, firms that are supported in this manner can get additional financing from financial institutions: a leverage effect. At the same time, subordinated debt is not as risky and hence does not allow leveraging the balance sheet of the company to the same extent as does share capital. To reflect this “hybrid” nature, subordinated debt is considered as liquidity support up to some ceilings. Beyond those ceilings, subordinated debt is instead considered as a recapitalisation instrument (see below). For subordinated debt that is below the ceilings, a higher level of remuneration for the State is envisaged.Footnote 84

-

The TF applies only to companies that operate in the real economy—and thus excludes financial institutions. Hence, aid should directly benefit that are undertakings active in the real economy, whereas banks act merely as financial intermediaries that channel the aid. To meet this goal, banks should pass on the advantages of the State guarantees or the subsidised interest rates on loans to the final beneficiaries.Footnote 85 This pass-through can take the form of: higher volumes of financing; lower collateral requirements; lower guarantee premiums; or lower interest rates than without such public guarantees or loans. The safeguards to ensure maximum pass-through should be particularly strong in cases where the aid takes the form of a State guarantee on existing loans, since the terms that are offered by the bank would not be disciplined by competition for new loans. The responsibility for putting in place strong safeguards that ensure maximum pass-through of the aid from the banks to the borrowers lies with the Member States.

5.4.3 Recapitalisation Framework

Because the COVID-induced crisis might be prolonged, the European Commission anticipated that “liquidity difficulties could turn into solvency problems for many companies.”Footnote 86 Accordingly, a recapitalisation framework was introduced into the TF (Sect. 3.11Footnote 87) with the second TF amendment. Several companies—notably in the hardest hit sectors, such as transport—appeared likely to record losses that would significantly erode their equity base and put their solvency at risk.

To reduce the risk of insolvency, the recapitalisation section envisages the provision of equity and hybrid capital instruments to firms in the real economy. MSs can acquire newly issued shares (ordinary or preferred)—“COVID shares”—or provide hybrid instruments with varying degree of risk characteristics. Such instruments may be formally recognised as debt or equity but would typically have an equity component: Under some triggering event, they can be converted into equity. Such measures can be granted until June 2021: This is later than the December 2020 deadlines for all of the other measures of the TF, both because solvency needs may arise with a lag and because such measures may require more planning than do liquidity measures.

Recapitalisation measures can have a very distortive effect on competition. Highly capitalised companies are able to obtain cheap financing in the markets and can therefore deploy aggressive commercial strategies. Consequently, if some firms are recapitalised but others are not, competition in the internal market might no longer take place on a level playing field. This concern justifies more stringent conditions on the commercial behaviour of the beneficiaries (governance conditions and distortion of competition measures) and stronger incentives to repay the aid. Accordingly, recapitalisation measures that exceed 250 m EUR need to be notified to the European Commission; and for these measures specific structural or behavioural commitments are required if the beneficiary has significant market power.

The European Commission has already dealt with a number of recapitalisation schemes and individual cases. Most individual decisions until now concern companies in the aviation sector. Indeed, the largest beneficiary of recapitalisation aid so far has been the German flag carrier, Lufthansa, with EUR 6 billion recapitalisation aid. Other individual cases include EUR 1 billion aid to SASFootnote 88 and EUR 250 million to Air BalticRecapitalisations schemes have already been approved for a number of countries—e.g., Germany (Commission Decision of 25 June 2020, Germany: COVID-19–Aid to Lufthansa (SA.57153 (2020/N)).),Poland (Commission Decision of 3 July 2020, Latvia: COVID-19–Recapitalisation of Air Baltic (SA.56943 (2020/N)).),.Spain (Commission Decision of 31 July 2020, Spain-COVID 19—Recapitalisation fund (SA.57659 (2020/N)). Commission Decision of 8 July 2020, Germany: COVID-19–Wirtschaftsstabilisierungsfonds (SA.56814 (2020/N)). Commission Decision of 17 September 2020, Italy-COVID 19—Patrimonio Rilancion project (SA.57612 (2020/N)).), and Italy,—and a large regional scheme for Bavaria was also vetted.Footnote 89 The largest of these schemes is the German proposal with an estimated budget of EUR 100 billionFootnote 90 to which one can add EUR 20 billion for the Bavarian program.Footnote 91 The Italian scheme is also sizeable: more than EUR 40 billion.

The main principles of the recapitalisation section include:

-

Eligibility criteria that require the identification of a market failure and the absence of alternative, economically viable options for beneficiaries.Footnote 92 In particular, eligible firms should not be able to get financing at affordable rates from financial institutions or from liquidity State aid schemes. Moreover the companies should play an “important role in the economy”—e.g., in terms of employment, innovation, or a systemic role—so that there are likely significant positive externalities from the provision of such aid.

-

The amount of the recapitalisation should also be proportional to the needs.Footnote 93 The aid provided must: (i) not exceed the minimum needed to ensure the viability of the beneficiary; and (ii) should not go beyond restoring the capital structure of the beneficiary to the one that predated the COVID-19 outbreak (December 2019). In practical terms, these are both forward-looking tests: The first leg of the test aims to ensure that the amount granted is limited to ensure that, in the foreseeable future, the company has a capital structure that would give it access to the capital markets.Footnote 94 The second leg specifies that the company should not have an improved capital structure (in terms of equity level or debt/equity) compared to the pre-crisis situation.

-

The recapitalisation instruments should provide support at preferential (aided) terms; however, there must be remuneration for the State, and this should increase over time to provide incentives for the companies to repay the aid.Footnote 95

For equity instruments, the capital increase should take place at a price that does not exceed the average share price of the beneficiary over the last 15 days (or the price that is established through an independent valuation if the company is not listed). Typically, capital increases in companies that face financial difficulties take place with a (significant) discount to the prevailing market price. The TF requires no such discount, which is the main element of support in the share capital instruments.

However, the remuneration of the State increases over time. The beneficiary can redeem the aid if it buys back the COVID shares by paying the higher of the nominal amount injected plus a reasonable remuneration, or the current market price. Hence the State also has a potential “up-side”. This “reasonable remuneration” increases over time to provide sufficient incentives to the company to redeem the aid as early as possible.

Finally, a step-up mechanism envisages the dilution of other shareholders if the COVID shares have not been redeemed (step-up mechanisms in years 4 and 6 for listed companies).Footnote 96 This mechanism provides incentives for the beneficiary to buy back the COVID shares to avoid the dilution effect.

For hybrid instruments, the remuneration is set on the basis of fixed credit spreads that, again, increase over time (from 225 to 250 bps in year 1 to 800-950 bps in year 8). These rates should be further increased to reflect the characteristics of the instrument, including the subordination and other modalities of payment (the deferral of coupon, etc.).

The German recapitalisation scheme is a good exampleFootnote 97: Additional increases have been requested in cases where the hybrid instrument is perpetual in nature and is subordinated to some parts of existing equity and where the coupons can be deferred at the discretion of the beneficiary. In the special case of instruments that are perpetual and have discretionary coupon payments (which undermines the financial incentives of the beneficiaries to pay back the instrument), governance conditions—such as dividend bans and limits on executive pay—are typically imposed until the repayment of the instrument.

Finally, if the hybrid instrument is converted into equity, there is dilution of existing shareholders since the conversion takes place at a discount relative to market price.

-

Governance conditions and distortion of competition measures.Footnote 98 Since recapitalisation measures can have significant distortive effects, an important ingredient of the TF is that supported firms should not engage in aggressive commercial expansion and should not take excessive risks.Footnote 99

In addition, for cases where firms receive recapitalisation aid of more than EUR 250 m and have significant market power in at least one relevant market, MSs must propose additional measures to preserve effective competition in those markets. These measures could be structural or behavioural.Footnote 100

The recapitalisation of Deutsche Lufthansa AG (DLH) is the first case where the MS submitted commitments to preserve effective competition. Due to the significant market power of DLH in the hub airports of Munich and Frankfurt, there are divestments of up to 24 landing/take-off slots/day at the Frankfurt and Munich hub airports and of related additional assets to allow competing carriers to establish a base of up to four aircraft at each of these airports. These measures would enable a viable entry or expansion of activities by other airlines at these airports to the benefit of consumers and effective competition.Footnote 101

Beneficiaries cannot advertise that they have received State aid (advertising ban). Also, large enterprises that receive such aid cannot acquire more than a 10% stake in competitors or other operators in the same line of business, including upstream and downstream operations: an acquisition ban. In exceptional circumstances, and without prejudice to merger control, beneficiaries may acquire a larger stake in operators upstream or downstream, if the acquisition is necessary to maintain the beneficiary’s viability. The rationale of this acquisition ban is to prevent recipients of aid from engaging in a spending spree to acquire competitors or suppliers.

In order to provide incentives to repay the aid and to ensure that the aid does not end up enriching existing shareholders, there is a dividend and non-mandatory-coupon ban. There is also a limit on the remuneration of management, which cannot exceed the fixed part of his/her remuneration on 31 December 2019: a bonus ban. These bans would apply as long as the (the great majority of) aid has not been redeemed.

-

Exit of the State: The TF provides strong incentives for the exit of the State in order to avoid a lasting “nationalisation” of the European economy. These incentives may be seen as a way to ensure the shareholding composition of the companies is not durably impacted by the crisis, while ensuring that the State receives sufficient remuneration.

This is best exemplified by point 64 of the TF: If the State sells the COVID shares in the market, the governance conditions cease to apply after four years irrespective of the value of these shares—even if the State has lost part of its original investment. This ensures that there is a realistic way for exit of the State for equity instruments irrespective of uncertain future market developments.Footnote 102

Finally, if after six years (seven for non-listed companies) the COVID-19 recapitalisation by the State’s has not been reduced below 15% of the beneficiary’s equity, a restructuring plan in accordance with the Rescue and Restructuring Guidelines must be notified to the Commission for approval. Such restructuring plans require actions to ensure the viability of the company and may require burden sharing.Footnote 103

5.5 Concluding Remarks

In times of serious disturbance of the real economy, normal State aid rules may be too restrictive or not specific enough to address the needs of the economy. The TF has been a necessary tool in ensuring that effective aid to companies in need can be channelled in a way that preserves the main principles of State aid. Liquidity and solvency support have been necessary ingredients of the national responses.

The current TF sets a comprehensive framework for such support. The more distortive types of aid must be accompanied by stringent conditions to ensure a level playing field among companies across the internal market. While the TF has a current deadline of December 2020, with the exception of the June 2021 deadline for recapitalisation measures, it cannot be excluded that the TF could be prolonged or adjusted after 31 December 2020—depending on the economic and public health developments.

Notes

A detailed overview of DG Competition’s activity can be found in its Annual Activity Report. The report also illustrates how DG Competition enforced the competition rules of the European Union in 2019. The 2019 Annual Activity Report is available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/annual-activity-report-2019-competition_en.

Case AT.40608. See press release available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_19_6109. The European Commission imposed interim measures on Broadcom, ordering it to stop applying certain exclusivity-inducing provisions that are contained in agreements with six of its main customers.

Case AT.40433. See press release available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_157. The European Commission fined BCUniversal LLC, (“NBCUniversal”) and other companies that belong to the Comcast group €14,327,000 for restricting traders from selling licensed merchandise within the European Economic Area (EEA) to territories and customers beyond those allocated to them.

Case AT.40528. See press release available at https://ec.europa.eu/competition/antitrust/cases/dec_docs/40,528/40528_410_6.pdf. The European Commission fined Spanish hotel group Meliá for including discriminatory clauses in its agreements with tour operators.