Abstract

In 2020–21, parents’ work-from-home days increased three-and-a-half-fold following the initial COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns compared to 2015–19. At the same time, many schools offered virtual classrooms and daycares closed, increasing the demand for household-provided childcare. Using weekday workday time diaries from American Time Use Survey and looking at parents in dual-earner couples, we examine parents’ time allocated to paid work, chores, and childcare in the COVID-19 era by the couple’s joint work location arrangements. We determine the work location of the respondent directly from their diary and predict the partner’s work-from-home status. Parents working from home alone spent more time on childcare compared to their counterparts working on-site, though only mothers worked fewer paid hours. When both parents worked from home compared to on-site, mothers and fathers maintained their paid hours and spent more time on childcare, though having a partner also working from home reduced child supervision time. On the average day, parents working from home did equally more household chores, regardless of their partner’s work-from-home status; however, on the average school day, only fathers working from home alone spent more time on household chores compared to their counterparts working on-site. We also find that mothers combined paid work and child supervision to a greater extent than did fathers.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In 2020, social distancing measures implemented in response to the health threat posed by the COVID-19 pandemic pushed many workers out of their workplaces into home offices to work remotely. According to the May 2020 Current Population Survey (CPS), 35.4% of workers reported working from home (WFH, also refers to work from home) at some point in the past month because of the pandemic (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020–2021). By January 2021, that percentage had fallen to 23.2% and continued to fall gradually after that.Footnote 1 And according to the American Time Use Survey (ATUS), 25.9% of all workdays with at least 4 h of work were WFH days from May 10, 2020 through December 2021, compared to only 7.9% of workdays in 2019.Footnote 2 WFH, either fully remotely or on a hybrid basis, is expected to continue at much higher rates around the world (Barrero et al., 2021; Bick et al., 2022; Erdsiek, 2021, 2022; Pabilonia & Vernon, 2022a, 2022b, 2022c).Footnote 3

This “natural” experiment in WFH due to the pandemic provides an opportunity to re-examine the gendered effects of WFH on childcare and household production for a larger group of parents WFH than previously possible and to analyze the allocation of unpaid work when both parents are WFH. However, during the pandemic, children were also more likely to be at home during core business hours, because many schools were hybrid or virtual, and many daycares and summer camps were closed (Burbio, 2021; Lee & Parolin, 2021; Russell and Sun, 2020).Footnote 4 This placed new demands on parents’ time, and WFH may have eased this additional care burden, especially for mothers, allowing them to work longer and simultaneously supervise their children. However, these were anything but normal times, as social distancing also restricted many leisure activities, potentially influencing how families spent their time together.Footnote 5

In this paper, we focus on the weekday workday time allocation of mothers and fathers in dual-earner couples with children under age 13, using daily time diaries from the 2015–2021 ATUS. Our primary goal is to analyze gender differences in time spent on paid work, childcare, and household production during the COVID-19 pandemic by the couple’s joint WFH status. However, we also examine how differences in time use between parents WFH and those working away from home (WAFH, also refers to work away from home) changed as a result of the pandemic.Footnote 6 We look at parents of young children, because children under age 13 generally need more supervision, and some state laws require parents to ensure that their young children are being supervised during the day (World Population Review 2022), while options for non-household-provided care during the pandemic were severely limited. We can identify the location of work for ATUS respondents directly from their diaries and thus determine if they worked exclusively from home on their diary days. However, because there is only one respondent and one diary per household, we do not observe the WFH statuses of their partners; therefore, we predict their probability of WFH. Because the survey contains information on who was present during each activity, we can also identify parents who do not appear to be using outside childcare options during core working hours (9 a.m. to 2 p.m.) on their WFH days and examine whether having a child at home impacted mothers’ and fathers’ time use differently.

During the pandemic, we find that a partner’s WFH status matters for how one allocates their time when WFH. Mothers’ and fathers’ time spent on childcare on weekday workdays rose substantially, whereas their time on household chores remained unchanged. When their partners worked away from home, parents WFH spent 3.4–5.2 h more on childcare and 0.5–0.8 h more on chores compared to their counterparts WAFH, although only mothers worked fewer paid hours. On the average school day, fathers, but not mothers, WFH alone spent about 1.5 h more on chores compared to their counterparts WAFH. When both parents were WFH compared to both WAFH, mothers and fathers maintained their paid hours even while spending more time on childcare. Compared to when WFH alone, mothers in full-time, dual-remotely-working couples spent 3.5 fewer hours and fathers 2 fewer hours supervising children, suggesting that having a partner WFH eased their care burden. When WFH and regardless of whether their partners were also WFH, mothers and fathers spent substantially more time supervising children if their children were at home rather than at school or daycare (5.6–7.1 h more) and directly interacting with children (1.7–3.5 h more), but the same amount of time on primary childcare. However, having a mother also WFH allowed fathers to spend a smaller percentage of their workdays supervising children at home.

On the average day during the pandemic, mothers’ total paid and unpaid workload was 0.7 h greater when WFH compared to fathers WFH than it was before the pandemic. However, mothers and fathers WFH did equally more total work compared to their WAFH counterparts, with no variation by their partners’ work locations.

2 Background

This paper fits into several literatures, including the literatures on gender and intra-household time allocation, WFH and intra-household time allocation, and the gendered division of household labor during the pandemic. In households with married or cohabiting couples, members of the couple jointly determine how much time to spend on paid and unpaid work. Theories on the economics of the household predict that their time spent on these activities will depend on relative earnings potential, productivity differences, labor market constraints on h, gender norms/identities, and differences in bargaining power (Becker, 1965, 1973, 1974; Bertrand et al., 2015; Lundberg & Pollak, 1994, 1996; Manser & Brown, 1980; McElroy & Horney, 1981; Schoonbroodt, 2018).

Even though men have increased their time in household production and childcare over the last few decades, there were still large gender gaps in unpaid work among employed parents prior to the pandemic. Employed mothers with children under age 13 spent over two hours more per day on unpaid work than did employed fathers (Bauer et al. 2021). Even among full-time dual-earner couples, mothers did most of the childcare (Alon et al., 2020a). And when they were breadwinners, wives still spent more time on household production (Bertrand et al., 2015).

Reducing the chores and care gaps may help mothers to participate to a greater extent in the labor market (Goldin, 2014, Samtleben & Müller, 2021). Flexible workplace polices, such as work location and hours scheduling flexibility, may help families close these gaps by allowing fathers to increase their time on these activities, although they may also allow mothers to take on extra unpaid work (Pabilonia & Vernon, 2022c).

Because of the pandemic-related school and daycare closures, the demand for household-provided childcare increased dramatically. Members of the couple could share this increased responsibility, but the proportional increase may also depend on whether the mother and/or father could WFH and how flexible their employer was with scheduling hours worked. For a detailed review of the empirical literature on the relationship between remote work and time allocation in the pre-pandemic period, see Pabilonia and Vernon (2022b). Overall, pre-pandemic, when remote work was relatively uncommon, fathers, but not mothers, spent more time on primary childcare on weekdays when WFH and on the average day if they were a remote worker, suggesting that increasing WFH days could close the gender care gap (Carlson et al., 2021; Lyttelton et al., 2022b; Pabilonia & Vernon, 2022c). However, mothers WFH spent about a half an hour more time doing paid work with a child in their presence than did fathers, suggesting that mothers chose to WFH to help balance their work and family responsibilities (Pabilonia & Vernon, 2022c). In addition, women increased their household production on WFH days, and shifted their time across days of the week (Carlson et al., 2021; Giménez-Nadal et al., 2019; Pabilonia & Vernon, 2022c).

Much of the research on the effects of the pandemic on time spent on paid work, childcare, and chores suggests that mothers carried the heavier load. Using a New York Times online poll conducted during the U.S. lockdown, Dunatchik et al. (2021) found that employed mothers’ and fathers’ time on housework and childcare increased, but mothers’ time increased relatively more, so the gender gap increased overall, although not among dual-WFH parents, who shared chores and childcare more equally. Using qualitative responses from the Understanding Coronavirus in America Tracking Survey, Zamarro and Prados (2021) found that in the initial months following the outbreak, mothers in coupled households were especially hard hit compared to fathers, reducing their work hours and increasing their childcare time when schools closed. Prior studies using the ATUS to examine the impact of the pandemic on parental time use in 2020 (Bauer et al., 2021; Augustine & Prickett, 2022), Lyttelton et al., 2022a, 2022b) found that employed mothers of children under age 13 spent 2.8 h more per weekday providing childcare than fathers during the pandemic, although the gender gap in parental time with young children had narrowed; mothers took on the additional educational and secondary childcare responsibilities, many of which they did while also WFH; parents WFH did not increase primary childcare; and mothers, but not fathers, in teleworkable jobs maintained their paid work hours to a greater extent than those WAFH.Footnote 7

In contrast, during the U.K. and the Netherlands lockdowns, Sevilla and Smith (2020) and Yerkes et al. (2020) found a drop in the gender care gap, with fathers picking up some of the increased demand for childcare and housework. this is consistent with earlier time-use research by Aguiar et al. (2013) and Bauer and Sonchak (2017), who found that during the Great Recession, U.S. men had relative increases in daily childcare hours. Also studying the initial lockdown period, but in Spain, a country a less egalitarian gender division in household labor, Farré et al. (2021) found that the gender gap in total hours of paid and unpaid work increased, although men slightly increased their time in home production. In Mexico, men also increased their time on housework, but not time caring for children (Hoehn-Velasco et al., 2022). Using real-time surveys conducted in March and April 2020 in the U.S., the U.K., and Germany, Adams-Prassl et al. (2020) found that among those WFH, mothers did more of the childcare than fathers. Although, in the U.S. and the U.K., mothers and fathers both reported spending about two hours per day homeschooling, while in Germany, mothers spent more time homeschooling their children compared to fathers. Zoch et al. (2021) also found that German mothers took on most of the extra childcare. During the fall of 2020, Sánchez et al. (2021) found for the U.K. that increases in the gender care gap had returned to pre-pandemic levels.

Several studies conducted outside the U.S. examined differences in the division of household labor by couples’ joint work location arrangements during the pandemic. Using longitudinal data on Swiss dual-earner coupled parents, Steinmetz et al. (2022) found that childcare depended highly on one’s own time availability, but housework depended on the time availability of the partner. Changes in time availability due to the increases in WFH during the lockdown period determined changes in childcare more than did the gender of the parent. Del Boca et al. (2020) found that among dual-earner couples in Italy, men WFH whose partners were WAFH after the coronavirus outbreak did more housework, and both men and women WAFH spent relatively less time on childcare and homeschooling than their counterparts WFH. In a survey of Italian women who were working under restrictions in April and November of 2020, Del Boca et al. (2022) found that men spent more hours on domestic activities when WFH and fewer hours on these activities when their partners were WFH. However, women’s domestic work hours did not depend on their partners’ work location arrangements, and they still carried the burden of the household responsibilities when both partners were WFH. Examining coupled parents in a German panel study, Jessen et al. (2022) found that during the spring 2020 lockdown when both parents were WFH, there was no increase in the percentage of households with the mother exclusively caring for the child, but there was a substantial increase when the mother was WFH alone. However, by the winter of 2020/2021, they find that the gender division of childcare returned to pre-pandemic levels, and when only fathers were WFH, they did more housework.

Using the CPS, Heggeness (2020) and Amuedo-Dorantes et al. (2022) found that the labor supply of mothers of school-aged children was more affected by school closures in the spring of 2020 than was fathers’ labor supply.Footnote 8 Kalenkoski and Pabilonia (2022) found that among married self-employed workers, mothers fared worse than fathers in terms of early employment and hours; but having a teleworkable job mitigated some of the negative effects on mothers’ paid work hours. They found no differences in hours reductions by teleworkable job status for married women without children. Collins et al. (2021) found that, on average, mothers decreased their work hours by 5%, but among couples who were potentially dual-remotely working, mothers of children aged 1 to 5 had a 4.5 times larger reduction in hours worked than fathers, suggesting that mothers bore the burden of the initial daycare closures.

Except for the qualitative study by Dunatchik et al. (2021), none of the prior studies examined how the WFH status of the other parent affects time allocation among members of dual-earner couples WFH living in the U.S. In part, it is because the ATUS provides information about only one parent’s day and work location. We offer here an innovative method to predict the WFH status of the other parent using the time diaries and compare differences in predicted hours by the couple’s joint work location. We also examine how the presence of a child at home on WFH days influenced parental time allocation.

We hypothesize that a parent WFH alone will pick up more of the childcare and chores (and potentially work fewer paid hours) due to their greater time availability. If both WFH, mothers and fathers may share the increased burden more equally. Yet, children may seek the attention of their mothers, who have been their primary caregivers, more often than their fathers, making it an empirical question what will happen when both caregivers WFH. If children are at home on schooldays, this may have a larger effect on mothers’ time use.

3 Data and descriptive statistics

3.1 American time use survey

The ATUS is a nationally representative sample of individuals in households who have recently completed their final CPS interview.Footnote 9 There is only one respondent per household and, besides updating some demographic and labor market information for the household members, the respondent completes a single day diary, sequentially reporting their primary activities from 4 a.m. on the day prior to the interview to 4 a.m. on the day of the interview. The only secondary activity reported on an ongoing basis is secondary childcare, which captures time when children under age 13 are under their care but not necessarily in the same room. For most activities, the respondent also reports where the activity took place and who was in the room with them if at home or who accompanied them if away from home (except for time sleeping, grooming, on personal activities, and when the respondent did not remember the activity or refused to answer). Estimates of time spent on activities from diaries are preferable to estimates from surveys asking respondents about usual time spent or time spent over the last week, as they suffer less from recall bias, aggregation bias, and social desirability bias (Juster, 1985; Robinson, 2002).

During the initial COVID-19 shutdown, ATUS interviewers did not conduct interviews from March 19, 2020 to May 10, 2020; thus, we use time diaries from May 10, 2020, after interviews resumed, through the end of 2021 as our pandemic period. To compare how time use by WFH status changed because of the pandemic, we compare diaries from our pandemic period to diaries collected from January 2015 to February 2020.

3.2 Analysis sample

Our main analysis sample includes fathers and mothers who are members of a dual-earner man-woman couple living with own household children under age 13 in which each member of the couple was aged 21–65.Footnote 10 We include married and cohabiting parents and control for cohabitation status in our multivariate analysis. Along with full-time workers, we include part-time workers and the self-employed, who generally have greater flexibility in scheduling the location and timing of their work hours. Our analyses focus on those interviewed about weekday workdays and who worked for at least one hour on their diary day in order to compare regular workdays with more normal working hours rather than include days when parents work for relatively brief spells of time such as taking an occasional phone call or answering an email as they stay in touch with the office. Our sample includes 728 parents in the pandemic period (May 10, 2020 through December 2021) and 2842 parents in the pre-pandemic period (January 2015 through February 2020). See Appendix Table 7 for further details of the sample construction. Throughout the analysis, we use ATUS final weights that we reweighted to ensure equal-day-of-the-week representation by gender and year for our parent sample. We also use replicate weights and compute empirically-derived standard errors, given the complex survey design.

In sensitivity analyses, we consider several subsamples of parents working during the pandemic, including parents who were full-time wage and salary workers and whose partners were also full-time wage and salary workers and who thus have more similar hours and less control over their scheduled work hours (N = 482), those interviewed during the school year (N = 490), and those WFH so we can observe how time use differed when a child was also at home (N = 280). Finally, for comparison’s sake, we examine members of dual-earner couples with no children under age 18 (N = 1854 before COVID and 611 during COVID).

3.3 Time use categories

We examine daily hours differences for three major activities—paid work, childcare, and household production—by the couple’s WFH status. We report estimates for work and work-related activities on all jobs, excluding commuting time.Footnote 11 We examine two different concepts of childcare: total childcare time, which comprises both primary and secondary childcare, and all time when at least one child is present in the same room during an activity when at home or accompanying the parent when away from home (we refer to the latter as “face time with children” and this measure includes time with teenage children). We also look at primary and secondary childcare separately. Primary childcare includes time spent on educational activities such as homework, but we do not examine educational time separately, as few reported this activity. It is likely that many parents were supervising children’s schooling time while doing another activity, and would thus be included in secondary childcare and face time with children. We also analyze time working while simultaneously caring for children (either in the same room or as a secondary activity). Household production includes activities such as cooking, cleaning, shopping for goods and services, household maintenance, and care of pets. Finally, we examine total work (paid and unpaid)—the sum of paid work, household production, and all other activities during which a child was present or secondary childcare was recorded.Footnote 12

3.4 Work-from-home status

For respondents, we determine their work location directly from their time diaries. If the respondent did all their paid work activities from home and no work on-site, then we classify them as WFH. Those classified as WAFH also may have done some WFH on their diary day, after working in the office, or worked in other locations, such as in a coffee shop, but they did not exclusively WFH.

Because we do not know their partner’s work location, we predict their partner’s probability of WFH. Using all pandemic-era ATUS respondents who were members of dual-earner couples, we estimate probit models by gender where the outcome variable is an indicator for WFH on the diary day and controls include a quadratic in age, log hourly wage, and indicators for cohabitation status, an extra adult in the household (in addition to the spouse/cohabiter), lives with child aged 0–2, lives with child aged 3–5, lives with child aged 6–12, lives with child aged 13–17, 3+ own children in household, education (no high school degree, some college, bachelor’s degree, advanced degree), paid hourly, part-time, partner part-time, self-employed, union member status, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic other race), living in a metropolitan area, 11 occupation groups, 14 industry groups, and months of the pandemic, and a continuous measure of how teleworkable their occupation is, which we construct from the CPS COVID-19 supplement question that asks whether any work was done at home because of the pandemic in the past 4 weeks.Footnote 13 Specifically, for the latter variable, we calculate the share of workers aged 21–65 who teleworked in the May 2020 through December 2021 CPS for each detailed occupation by year and Census region and assign that share to the respondent and partner by their detailed occupation code (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Census Bureau 2020–2021).Footnote 14 While some workers were regularly working from home pre-pandemic, the take-up rate by occupation because of the pandemic corresponded strongly with the pre-pandemic take-up in teleworkable occupations (Dey et al., 2021). After obtaining the probit coefficients by gender, we then predict WFH status for the respondents and for their partners using their respective characteristics.

The correlation between our predicted probabilities and actual WFH for respondents is 0.55 for men and 0.60 for women. Partners’ predicted probabilities of WFH range from zero to one (see Appendix Fig. 12). Using these probabilities, 41% of fathers’ partners (i.e., mothers) and 30% of mothers’ partners (i.e., fathers) were classified as WFH, which is similar to the percentages WFH by gender for our respondents (Table 1). Predicted probabilities suggest that we have a lot of dual-WFH couples. Among parents WFH, 50% had partners with a WFH probability exceeding 50%, and 25% had partners with a WFH probability exceeding 72%.

3.5 Childcare constraints

To capture the impact of school and daycare closures or children who are home under quarantine, we construct a child-at-home indicator variable. Specifically, we identify whether the respondent either reported that a child was present in the room or they were doing secondary childcare for at least five minutes during the core work/school hours of 9 a.m. and 2 p.m. On weekday WFH days during the pandemic, 54% of fathers and 65% of mothers had at least one child at home during core hours, while pre-pandemic only 35% of fathers and 58% of mothers had a child at home during core hours (Table 1).

3.6 Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents summary statistics for our pre-pandemic and pandemic parent samples by gender. We see that the composition of the sample during the pandemic differed from the composition of the pre-pandemic sample along a few dimensions—parents earned higher wages, fathers were less likely to have a partner working part-time, fathers were more likely to have a child at home on WFH days, fathers were more likely to be working in a computer or math occupation and less likely to be working in a services occupation, mothers were more likely to have a graduate degree, mothers were more likely to be working in a management or administrative industry and in a business or finance occupation, and parents were more likely to be WFH and to live in the Northeast.

Figure 1 shows that the percentage of weekday workdays worked exclusively from home increased dramatically for mothers and fathers during the pandemic, with mothers having substantially higher WFH take-up rates. Before the pandemic, only 7.5% of fathers’ workdays and 13.1% of mothers’ workdays were spent WFH. During the pandemic, 29.8% of fathers’ workdays and 39.5% of mothers’ workdays were worked from home—a three-and-a-half-fold increase in WFH.

Percentage of weekday workdays worked exclusively from home by parents before and during the pandemic. The Pre-COVID period includes diaries between January 2015 and February 2020, while the COVID period include diaries between May 10, 2020 and December 2021. Sample is based on parents aged 21–65 in dual-earner couples with children under age 13. Workdays are days on which the respondent reports at least 1 h of work. Sample sizes: fathers = 1447 and 391 and mothers = 1395 and 337 for the pre-COVID and COVID samples, respectively. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the American Time Use Survey

Comparing unadjusted means for our major time-use categories across time and gender, we find that, on average, mothers and fathers in dual-earner couples spent substantially more time caring for their children on weekday workdays during the pandemic—fathers spent 1.2 h more while mothers spent 1.7 h more (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Almost all this additional time was in secondary childcare while doing other activities (see Table 1). As a result, the gender care gap increased by 0.5 h, from 1.8 to 2.3 h. Mothers and fathers also increased their total face time with children by about half an hour. Fathers worked 0.3 fewer paid hours during the pandemic, whereas mothers worked 0.3 h more, so the gender gap in paid work hours fell from 1.5 h before the pandemic to 0.9 h during the pandemic. Time spent on household production did not change, on average, although there was a statistically significant gender chores gap in both periods (a gap of 0.6–0.8 h). Overall, the gender gap in total hours of work (paid and unpaid) increased slightly, from 0.4 to 0.6 h.

Average hours per weekday workday, by gender. The Pre-COVID period includes diaries between January 2015 and February 2020, while the COVID period include diaries between May 10, 2020 and December 2021. Sample is based on parents aged 21–65 in dual-earner couples with children under age 13. Workdays are days on which the respondent reports at least 1 h of work. Childcare includes both primary and secondary childcare. Sample sizes: fathers = 1447 and 391 and mothers = 1395 and 337 for the pre-COVID and COVID samples, respectively. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the American Time Use Survey

Looking at the unadjusted means for our major time-use categories by WFH status during the pandemic (Fig. 3), we find no statistically significant difference in mothers’ paid work hours, while fathers WFH worked 0.9 fewer paid hours than those WAFH (8.8 vs. 7.9 h). The largest differences in means by work location were in childcare time, especially for mothers. Mothers WAFH spent 5.5 h caring for children while mothers WFH spent 9.5 h.Footnote 15 Fathers WAFH spent 3.8 h caring for children while fathers WFH spent 6.9 h. There were also sizeable differences in face time with children by work location. Mothers WAFH spent 4.2 h with children while those WFH spent 6.0 h. Fathers WAFH spent 3.0 h with children while those WFH spent 4.5 h. We find no statistically significant difference in mothers’ hours spent on household production by work location. Fathers WFH, on the other hand, spent 0.5 h more on household production than those WAFH, 1.3 vs. 0.8 h.

Average hours per weekday workday during the pandemic, by gender and work location. Sample is based on parents aged 21–65 in dual-earner couples with children under age 13 interviewed about days between May 10, 2020 and December 2021. Workdays are days on which the respondent reports at least 1 h of work. WFH is defined as working exclusively from home on the diary day. WAFH is defined as working away from home at any point on the diary day. Childcare includes both primary and secondary childcare activities. Sample sizes: fathers = 259 and 132 and mothers = 189 and 148 for WAFH days and WFH days, respectively. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the American Time Use Survey

Figures 4 and 5 show the percentage of fathers and mothers spending time with their children by the time of day and location of their work before and during the pandemic. For fathers WFH, we see a slight increase during the pandemic in the percentage spending time with children around noon, when children are usually in school (Fig. 4). However, we observe a decrease in the percentage spending time in the morning hours (around 8 a.m.) and after-school hours (between 2 p.m. and 5 p.m.), which might reflect differences in the school location (virtual or in-person) or in the composition or preferences of fathers WFH. For example, prior to the pandemic, fathers WFH may have been responsible for dropping off and/or picking up their children at school. For mothers WFH, we see that they spent less time with children before school hours, at noon, and during after-school hours during the pandemic, though mothers WFH spent more time with their children in the after-school hours than mothers WAFH in both periods (Fig. 5). On the other hand, for mothers WAFH, a slightly larger percentage spent time with a child between 9 a.m. and 1 p.m., when children may have been in virtual schooling.

Percentage of fathers spending time with children on weekday workdays, by time of day and work location. The Pre-COVID period includes diaries between January 2015 and February 2020, while the COVID period include diaries between May 10, 2020 and December 2021. Sample is based on mothers and fathers aged 21–65 in dual-earner couples with children under age 13. Workdays are days on which the respondent reports at least 1 h of work. WFH is defined as working exclusively from home on the diary day. WAFH is defined as working away from home at any point on the diary day. Time with children is time spent doing activities when children are in the same room while at home or when accompanied by children when away from home. Sample sizes: Pre-COVID WAFH = 1321, Pre-COVID WFH = 126, COVID WAFH = 259, COVID WFH = 132. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the American Time Use Survey

Percentage of mothers spending time with children on weekday workdays, by time of day and work location. The Pre-COVID period includes diaries between January 2015 and February 2020, while the COVID period include diaries between May 10, 2020 and December 2021. Sample is based on mothers and fathers aged 21–65 in dual-earner couples with children under age 13. Workdays are days on which the respondent reports at least 1 h of work. WFH is defined as working exclusively from home on the diary day. WAFH is defined as working away from home at any point on the diary day. Time with children is time spent doing activities when children are in the same room while at home or when accompanied by children when away from home. Sample sizes: Pre-COVID WAFH = 1202, Pre-COVID WFH = 193, COVID WAFH = 189, COVID WFH = 148. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the American Time Use Survey

During the pandemic, mothers and fathers WFH spent 7 and 18% of their work hours with children in the same room, respectively (Fig. 6). Although prior to the pandemic fathers WFH spent about the same percentage of their workday with children, mothers WFH during the pandemic spent more of their workday with children present than in the pre-pandemic period (a 4-percentage-point difference). Parents spent even more time WFH with children in their care (secondary childcare). Because of the pandemic, mothers WFH increased the percentage of their workday doing secondary childcare from 39 to 52%. Fathers WFH spent 28% of their workday on secondary childcare before the pandemic and 31% of their workday on secondary childcare during the pandemic, but the difference was not statistically significantly. In both periods, mothers WFH had more work episodes than mothers WAFH (2.7 episodes vs. 2.3 episodes during the pandemic and 3.0 episodes vs. 2.4 episodes in the pre-pandemic period) (Fig. 7). On the other hand, fathers WFH experienced fewer interruptions in their work during the pandemic than prior to the pandemic (2.4 episodes vs. 2.9 episodes), which would be consistent with fathers positively selecting into WFH to attend to family matters in the pre-pandemic period or fathers working fewer hours during the pandemic. Thus, mothers potentially experienced more disruptions from their children while WFH during the pandemic than did fathers. We also see that mothers and fathers WAFH spent more of their workday with children under their care during the pandemic than in the pre-pandemic period, which likely results from their having worked more partial days from home (Fig. 6).

Percentage of work hours simultaneously caring for children on weekday workdays. The Pre-COVID period includes diaries between January 2015 and February 2020, while the COVID period include diaries between May 10, 2020 and December 2021. Sample is based on mothers and fathers aged 21–65 in dual-earner couples with children under age 13. Workdays are days on which the respondent reports at least 1 h of work. WFH is defined as working exclusively from home on the diary day. WAFH is defined as working away from home at any point on the diary day. Secondary childcare can include time when children are under a parent’s supervision but in another room in the house or in the yard. Sample sizes: Pre-COVID WAFH = 1321, 1202; Pre-COVID WFH = 126, 193; COVID WAFH = 259, 189; COVID WFH = 132, 148 for fathers and mothers, respectively. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the American Time Use Survey

Number of work episodes on weekday workdays. The Pre-COVID period includes diaries between January 2015 and February 2020, while the COVID period include diaries between May 10, 2020 and December 2021. Sample is based on mothers and fathers aged 21–65 in dual-earner couples with children under age 13. Workdays are days on which the respondent reports at least 1 h of work. WFH is defined as working exclusively from home on the diary day. WAFH is defined as working away from home at any point on the diary day. Sample sizes: Pre-COVID WAFH = 1321, 1202; Pre-COVID WFH = 126, 193; COVID WAFH = 259, 189; COVID WFH = 132, 148 for fathers and mothers, respectively. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the American Time Use Survey

Figure 8 shows that during the pandemic, there was a significant percentage of parents WFH with children present or under their care between 8 a.m. and 12 p.m., when children are normally in school. This was especially true for mothers. Many were likely supervising their children’s online studies while WFH. Compared to fathers WFH, mothers WFH were less likely to be working in the afternoon hours (3 p.m. to 6 p.m.) and slightly more likely to be working later in the evening (8 p.m. to 11 p.m.). Thus, some mothers likely shifted the timing of their work to after their children had gone to bed for the night.Footnote 16 However, this bump up in work after dinner does not appear to be unique to the pandemic period. Figure 9 shows that prior to the pandemic, mothers WFH were more likely than mothers WAFH to work in the evenings, perhaps because their work computers were easily accessible. Looking at NLSY97 respondents in the spring of 2021, Aughinbaugh and Rothstein (2022) found that among those WFH, mothers were more likely to report that children’s remote learning made it difficult to work or do other household tasks than were fathers (65 vs. 58%). Overall, we find that many parents, especially mothers, who were WFH were doing so with children or under their supervision during the pandemic, which could have negatively affected their productivity while working (Adams-Prassl, 2021).

Percentage of parents working, working with a child present, and working while supervising a child on weekday workdays while working from home during COVID, by time of day and gender. Sample is based on parents aged 21–65 in dual-earner couples with children under age 13 interviewed about days between May 10, 2020 and December 2021. Workdays are days on which the respondent reports at least 1 h of work. Face time is time with a child in the same room. Secondary childcare includes time with a child in the room or in another room in the home or in the yard. Sample sizes: fathers = 132 and mothers = 148. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the American Time Use Survey

Percentage of parents working by work location in the Pre-COVID era. Sample is based on parents aged 21–65 in dual-earner couples with children under age 13 interviewed about days between January 2015 and February 2020. Workdays are days on which the respondent reports at least 1 h of work. Face time is time with a child in the same room. Secondary childcare includes time with a child in the room or in another room in the home or in the yard. Sample sizes: Fathers WFH = 126; Mothers WFH = 193; Fathers WAFH = 1321; Mothers WAFH = 1202. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the American Time Use Survey

Using a separate set of parents who were interviewed about weekend days, we investigate whether parents worked more on the average weekend day during the pandemic, potentially shifting their work from weekdays to weekend days as they struggled to care for their children and supervise their studies. Figure 10, however, shows that mothers and fathers worked the same number of weekend hours in both periods.Footnote 17 Thus, some mothers and fathers may have shifted some of their hours to evenings, especially since more of them were WFH than ever before, but not to weekends, to balance their work and childcare responsibilities.

Average hours worked on weekend days for parents in dual-earner couples. The Pre-COVID period includes diaries between January 2015 and February 2020, while the COVID period include diaries between May 10, 2020 and December 2021. Sample is based on parents aged 21–65 in dual-earner couples with children under age 13. Estimates are for the average weekend day, including any amount of work as well as zeros. Sample sizes: fathers = 556 and 145 and mothers = 7507 and 116 for the Pre-COVID and COVID samples, respectively. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Hours differences are not statistically significant over time or by gender. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the American Time Use Survey

4 Econometric models

As a baseline specification, for parents interviewed in 2015–21 about weekday workdays, we estimate the following linear model that allows time use to vary by gender, the respondent’s WFH status, and over time by ordinary least squares (OLS):Footnote 18

where Yi is time spent on an activity measured in hours per weekday workday for individual i, Femalei is an indicator variable for whether the individual is female, WFHi is an indicator variable for whether the individual was working exclusively from home on their diary day, COVIDi is an indicator variable equal to 1 if the diary day was between May 20, 2020 and December 2021 and 0 otherwise, Xi is a vector of control variables, and νi is the error term. In all specifications, control variables include a quadratic in age, log hourly wage, and indicators for cohabitation status, an extra adult in the household (in addition to the spouse/cohabiter), age of youngest household child, 3+ own children in household, education (no high school degree, some college, bachelor’s degree, advanced degree), paid hourly, part-time, partner part-time, self-employed, union member, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic other race), living in a metropolitan area, 11 occupation groups, 14 industry groups, and Census region, month, and year. γ0 is a constant term. The coefficients γ1 through γ7 and the coefficient vector γ8 are to be estimated. By including the interactions between Female, WFHi, and COVIDi, this model allows us to test whether COVID has changed the WFH–WAFH gaps in paid work, chores, and childcare by parental gender.

Next, restricting to parents interviewed during the COVID-19 era only, we estimate linear models by OLS where we add interaction terms between Femalei, WFHi, and PARTNER_WFHi to allow the gendered effects of WFH to vary by the couple’s joint work location during the pandemic given the significant rise in WFH:

where Yi, Femalei, and WFHi are as defined above, PARTNER_WFHi is the predicted probability that the partner was WFH, Xi is the vector of control variables described previously, except that we include indicators for pandemic month instead of year and month indicators to better correct for the timeline of the pandemic, and εi is the error term. β0 is a constant term. The coefficients β1 through β7 and the vector of coefficients β8 are to be estimated.

In a third model, we restrict the sample to WFH days during the COVID-19 era and estimate linear models by OLS as follows:

where CHILDHOMEi is an indicator variable for whether a child was at home between 9 a.m. and 2 p.m. and the other variables are as defined above. α0 is a constant term. The coefficients α1 through α7 and the coefficient vector α8 are to be estimated. ηi is the error term. By including interactions between Femalei, CHILDHOMEi, and PARTNER_WFHi, this model allows us to test whether time use varied on WFH days by whether a child was also at home by parental gender and whether having a partner at home reduced caregiving time as parents shared the additional childcare burden resulting from the pandemic.

5 Results

For ease of interpretation, given the numerous interaction terms in the econometric models, we predict average daily hours for activities on weekday workdays and discuss differences in these predicted hours for members of dual-earner couples by own WFH status, by couple’s joint WFH status, and by child-at-home status among those WFH. For our main results, coefficient estimates are also available in Appendix Tables 10 and 11.

When we control for the partner’s WFH probability and its interaction with the respondent’s WFH status, we calculate predictions setting PARTNER_WFHi equal to 0 to indicate a WAFH day and equal to 0.75 to indicate a WFH day. The latter WFH probability is roughly the 86th percentile of the distribution of the predicted WFH probabilities for dual-earner coupled parents (see Appendix Fig. 12).Footnote 19

5.1 Baseline results: pre-pandemic vs. pandemic WFH–WAFH differences for parents

In Table 2, we show differences in time spent on weekday workdays in both the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods for parents by WFH status from Eq. 1, when we do not control for partner’s WFH status. Thus, the differences show how fathers and mothers WFH spent their time compared to their counterparts WAFH on average, and we also test whether that difference changed over time and differed by gender. Prior to the pandemic, workers may have chosen to WFH based on unobserved preferences for spending time with children and working, or because they had extenuating circumstances such as caring for a child with a disability. They also may have chosen a job allowing more flexible hours, allowing them to optimize their time with their children. Likewise, employers may have been selective in whom they allowed to WFH, perhaps choosing their most trustworthy or productive workers. The pandemic is a unique setting to study the impact of WFH, because many of these selection issues are minimized. Yet, the pandemic created other issues: workers saw their non-household childcare options diminish and choices for leisure activities reduced. They also may have been concerned about the health threat and thus chosen to keep their children home and to reduce their leisure activities. Those who could work from home were also more likely to be in full-time good-paying jobs, and many were WFH who had never done so before (Bonacini et al. 2021; Marshall et al. 2021; Parker et al. 2020). They were also more likely to have a partner working alongside them. Thus, we expect to see differences in how workers spent their time when WFH vs. a traditional workplace in these two periods, as the composition of the groups of workers has changed by work location.

The first two rows of each panel of Table 2 highlight the parental gender gaps in time spent on activities for those WAFH and then those WFH, while controlling for demographic and job characteristics. Regardless of WFH status, mothers worked 0.9–1.0 fewer paid hours per day than did fathers before the pandemic. During the pandemic, mothers WAFH worked 0.4 h fewer than fathers, while mothers and fathers WFH had similar work hours.

The next two rows of each panel show WFH–WAFH differences for fathers and then mothers, followed by a row showing whether these differences were larger for mothers than for fathers. In both periods, fathers WFH worked fewer paid hours than fathers WAFH (1.3 h before and 0.7 h during). Mothers WFH also worked fewer hours than mothers WAFH (1.4 h before and 0.5 h during). Thus, the work location differences in paid work diminished during the pandemic for both. We see these differences in the “COVID minus pre-COVID” panel, which presents the differences between the first set of gaps and the second set to show the net change during COVID. During COVID, mothers’ paid work time increased relative to fathers’, more so among parents WFH, and paid work hours became more similar for WFH and WAFH workers.

Before COVID, all mothers spent 1.1 h more on total childcare than did fathers. During COVID, the gender gap grew for WFH parents to 2.4 h because WFH mothers added an additional 1.3 h of childcare (see regression coefficients in Appendix Table 10). The extra 1.3 h was a combination of additional primary and secondary time.

In both periods, on average, WFH allowed both parents to spend more time with children: fathers WFH spent 0.3–0.4 h more on primary childcare, almost 3 h more on secondary childcare, and 1.5–1.9 h longer with children in their presence compared to fathers WAFH. Mothers WFH spent over 2 h more in the presence of children compared to WAFH mothers. Before the pandemic, mothers WFH spent 3.4 h more in total childcare than mothers WAFH, and during COVID, their WFH–WAFH gap increased by 1.1 h (with roughly equal increases in primary and secondary childcare). As a result, the gender difference in the WFH–WAFH care gap, which was essentially zero before COVID, increased by 1.3 h. Thus, on average, WFH mothers bore the brunt of the increased demand for household-provided childcare.

Mothers spent more time on household production than fathers, regardless of their WFH status. Before the pandemic, mothers WFH spent 0.6 more hours on household production compared to mothers WAFH, but during the pandemic, this WFH–WAFH hours gap for mothers fell to 0.4, though the difference over time is not statistically significant. In both periods, fathers WFH spent more time on household chores relative to those WAFH (0.5–0.6 h).Footnote 20 The gender differences in the WFH–WAFH gaps in chores are not statistically significant.

Finally, mothers’ total work burden was similarly higher than fathers’ among those WAFH in both periods. Before the pandemic, mothers WAFH did 0.4 h more total work per day than fathers, whereas mothers and fathers WFH spent the same time in total work. During COVID, the gender gap increased by 0.7 h for mothers WFH relative to fathers WFH, suggesting less equal allocation of work. In both periods, fathers and mothers WFH did more total work than their counterparts WAFH (0.5–0.9 h differences depending on the period and gender, with no statistically significant differences between groups).

5.2 Results for parents, controlling for partner’s WFH status during the pandemic

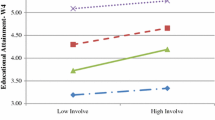

In Table 3, we present differences in predicted hours spent on the activities of one parent during COVID by the couple’s joint WFH status from Eq. 2. In rows 1 and 2, we show the WFH–WAFH hours gap for fathers and then mothers when their partners WAFH. Row 3 shows the gender difference in these gaps. Rows 4 and 5 show differences in time allocation when both partners WFH vs. both partners WAFH. Row 6 shows how much larger the difference is for mothers than fathers. In rows 7–8, we show differences in predicted hours for the parent WFH when both partners WFH vs only one member of the couple works from home. Negative values in these latter rows indicate that having a partner also WFH eases the parent’s paid and unpaid work burden (or interferes with a paid workday). For a visual display of these WFH–WAFH differences, see Fig. 11.

WFH–WAFH hours gaps during COVID-19 by couple’s joint work location. N = 728. Bars represent WFH–WAFH differences from estimating Eq. (2), while error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. The COVID-19 sample includes diaries between May 10, 2020 and December 2021. WFH is defined as working from home at least 1 h on the diary day for the respondent. Partner WFH is based on the predicted probability of working from home. Time-use predictions are based on setting partner WFH = 0.75 for WFH and = 0 for WAFH. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the American Time Use Survey and Current Population Survey COVID-19 data

Looking first at paid work, we find that mothers WFH alone spent 1.1 fewer hours working than mothers WAFH. When both partners WFH, mothers WFH spent the same amount of time working as mothers WAFH. This suggests that mothers were able to maintain their work hours during the pandemic if their partners were also WFH. In this specification that adjusts for month of the pandemic, we do not find that fathers’ labor supply was affected by either their work location or their partner’s work location, even though the results in Table 2 that included the pre-COVID era indicate that on average fathers WFH did less paid work than fathers WAFH.

When WFH alone, both fathers and mothers spent more time caring for their children compared to their counterparts WAFH (3.4 and 5.2 h, respectively). Most of the additional care time was in secondary childcare (3.1 and 4.4 h for fathers and mothers, respectively), but mothers also spent more time on primary childcare (0.8 h). Parents WFH also had more face time with their children (1.4 and 2.5 h for fathers and mothers, respectively). None of the gender differences in the WFH–WAFH gaps in childcare are statistically significant when parents WFH alone.

When both parents were WFH, fathers and mothers WFH spent 2.1 and 3.2 h more, respectively, on childcare (primarily on secondary childcare); the 1.1-hour gender difference is not statistically significant. Both parents also spent more time in the same room with their children (1.1 and 1.5 h for fathers and mothers, respectively, again the difference is not statistically significant). Compared to those WFH alone, mothers in dual-WFH couples spent 2.0 fewer hours on childcare, suggesting that having a partner also WFH eased their childcare burden, but the estimate is imprecise.Footnote 21 Although many fathers may also have had some relief, judging by the large negative difference in the second to last row, we cannot reject the hypothesis that fathers WFH alone spent the same amount of time on childcare as those WFH with a partner.

We find that parents WFH alone spent more time on household production. The WFH–WAFH gaps in household production are substantially lower when their partners also WFH, but the differences by partner’s WFH status are imprecise. Finally, parents’ total work burden was 0.9 h higher when WFH alone and about 0.5 h higher for each in dual-WFH couples relative to when both were WAFH, but the differences by partner’s WFH status are not statistically significant.

5.3 Parents in full-time wage and salary dual-earner couples

Dual-earner couples who both maintained full-time work hours and worked for an employer during the pandemic faced even tighter constraints on their time. In Panel A of Table 4, we show that mothers WFH alone worked 1.5 fewer paid hours compared to mothers in WAFH couples (only a 0.4-hour-larger difference than we found in the full sample). We again find no difference in paid work hours for dual-WFH vs dual-WAFH parents.

When WFH, full-time employed parents spent more time caring for children relative to their counterparts WAFH, including those WFH alone (4.5 and 6.6 h, respectively) and those WFH with their partners (2.3 and 3.1 h). As in the main sample, additional childcare time was largely due to secondary childcare, but full-time employed parents also spent 0.7–1.0 h more on primary childcare when WFH. Results suggest that WFH with a partner eased these parents’ care burden substantially compared to WFH alone (by 3.5 h for mothers and 2.2 h for fathers), though only mothers’ difference by partner’s WFH status is statistically significant. The differences by partner’s WFH status were entirely due to differences in secondary childcare. Compared to in the full sample, full-time employed fathers WFH alone spent more face time with children compared to those in WAFH couples (2.5 h more compared to 1.4 h more). We cannot reject the hypothesis that those WFH with a partner spent an equivalently larger amount of time with children, though the WFH–WAFH differences are substantially smaller (1.1–1.4 h).

In this subsample, the differences in household production and total work for one parent WFH are slightly smaller in magnitude than in the full-sample and not statistically significant, nor are the differences significant when WFH with a partner. However, we find that fathers WFH with a partner do less household production than fathers WFH alone, suggesting that having a partner also WFH eases fathers’ chores burden. We do not find any statistically significant differences in the WFH–WAFH gap in total work.

Thus, we find evidence that partner’s work location affects mothers’ paid work and childcare time and fathers’ household production time when they WFH. In addition, the results using both the full sample of dual-earner parents and the subsample of full-time wage and salary dual-earner parents suggest that the gender care gap increases when mothers WFH alone, but when only fathers WFH, the gender care gap decreases. When both WFH compared to mother works from home alone, results suggest that the gender care gap decreases.

5.4 School-year diaries

We also examine differences in predicted hours spent on activities on school-year weekday workdays, when parents were more likely to be differentially affected by school closures, given that mothers more often report that they are the primary caregivers responsible for children’s schooling activities (Dunatchik et al. 2021). In this subsample, we cannot reject the hypothesis that mothers WFH alone worked similar hours to those WAFH. However, we find that when their partners WFH as well, mothers’ WFH–WAFH difference in paid work was relatively larger than fathers’ difference. In addition, mothers WFH with a partner worked 1.5 h more than mothers WFH alone, which suggests that having a partner also WFH helped mothers maintain their work hours.

Although we find no evidence that parents’ paid work fell on school days when WFH alone, fathers WFH alone spent 3.3 h more on secondary childcare and 2.1 h more with children (the latter difference is 0.6 h greater than when we include summer workdays). Mothers WFH alone spent more time on primary childcare (0.9 h), secondary childcare (3.6 h), and face time with children (2.0 h). Compared to results for the full sample, mothers’ WFH–WAFH gaps in secondary childcare and face time when WFH alone were smaller. When both WFH compared to both WAFH, mothers’ WFH–WAFH gap in childcare was 3.0 h while fathers’ gap was 1.6 h, but imprecise. We cannot reject the hypothesis that the gender difference in the WFH–WAFH gaps is zero. When both WFH compared to one parent works from home and as we found in the full sample, parents’ total childcare burden was eased, with fathers’ spending 2.1 fewer hours on childcare, primarily through a reduction in secondary childcare, and mothers’ spending 1.5 fewer hours on childcare (as in the full sample, the estimates are imprecise). Compared to the full sample estimates, the WFH–WAFH gaps in face time when both parents WFH compared to both WAFH are small and not statistically significant. When both parents WFH compared to one parent works from home, results again suggest that having a partner also WFH decreases the time one spends with children, although again the estimates are not precisely estimated.

Turning to household production, we find that fathers, but not mothers, WFH alone spent 1.5 h more on chores than fathers WAFH, and the gender difference is statistically significant. It may be that mothers did not spend more time on household production because they focused on supervising online schooling.Footnote 22 However, when both WFH, parents WFH spent similar amounts of time on household production as their WAFH counterparts, suggesting that fathers’ chores burden was eased by having mothers also WFH, and the difference for fathers WFH by partner’s WFH status is statistically significant (1.1 fewer hours). Finally, when fathers WFH alone their total work burden was 0.9 h higher, as we saw in the full sample, but the estimate is imprecise in the smaller sample. We cannot reject the hypothesis that mothers WFH alone also had a higher work burden, nor can we reject the hypothesis that partner’s WFH status does not matter for the total work burden.

5.5 Childcare constraints

Many parents WFH did so with a child at home during the day. To examine the impact of these additional childcare constraints, we restrict the sample to those WFH and examine how their time differed by whether a child was also at home and whether those differences also varied by their partners’ WFH status (Table 5). In this analysis, the parent did not have to be working at the same time as caring for their child. They may have cared for their child during the child’s school day, or when their preschool-aged child was more alert in the morning, and done their paid work later in the day, as employers expanded their work flextime policies during the pandemic.Footnote 23 We also estimate a specification that tests for differences in the share of the parent’s workday doing secondary childcare.

First, we compare time spent on activities by child-at-home status for those with partners WAFH. Being the only parent WFH with a child at home meant spending more time on secondary childcare (7.1 and 6.0 h for fathers and mothers, respectively) compared to WFH while children were all at school during the day. It also meant spending more time with a child in the same room (2.3 and 3.3 h for fathers and mothers, respectively).Having a child at home affects mothers and fathers roughly equally. Having a child at home reduced parental time spent in paid work when WFH alone, although the impact is not statistically significant, and parents WFH alone spent substantially more time working while simultaneously caring for a child (a 70–78-percentage-point difference). For parents WFH alone, we cannot reject the hypothesis that having a child at home had no impact on their time spent on primary childcare and household production. Mothers’, but not fathers’, total workload was greater when a child was at home while they were WFH alone.

Having the second parent WFH did not reduce parents’ additional time on secondary childcare when a child was at home instead of in school. However, compared to when WFH alone, fathers spent less of their workday simultaneously caring for a child (28 percentage-points less). When both parents were WFH, parents spent more time with children in the same room if their child was at home, but mothers spent relatively more face time with children and a greater percentage of their workday supervising children compared to fathers, though the gender differences are imprecise (1.7 h more and a 17 percentage-points greater difference, respectively). Parents in dual-WFH couples did not spend more time in primary childcare nor did they reduce their paid work when a child was at home. However, fathers spent 0.5 h more on household production when a child was at home, and we cannot reject the hypothesis that mothers did the same. Parents’ total workload was 1.1–1.3 h greater when both parents WFH and a child was at home rather than at school. The child-at-home gap in total work for fathers was 1.6 h larger when their partners were WFH than when they were WFH alone.

5.6 Members of dual-earner couples without children under age 18

For comparison’s sake, we also estimated Eqs. 1 and 2 using members of dual-earner couples without household or non-household dependent children (Table 6). Before the pandemic, women WAFH worked 0.3 fewer hours than men WAFH, while the gender gap for those WFH was not statistically significant. During the pandemic, there were no gender differences in paid work time, regardless of work location, but we cannot reject the hypothesis that the gender difference for those WAFH was the same as before COVID. When WFH compared to WAFH, men and women worked 0.6–1 fewer hours, with no statistically significant differences between the two time periods. Compared to our findings for fathers and mothers (Table 2), the differences in paid work for childless men and women were smaller, except for the WFH–WAFH difference for childless women, which was about the same.

In both periods, childless women spent 0.4–0.5 more hours on household production than did childless men, regardless of work location, which is similar to the gender gap in chores that we found for fathers and mothers. Men and women WFH spent 0.4–0.8 h more on household production than their counterparts WAFH, with no statistically significant differences over time or by gender. Compared to what we found for fathers and mothers, the WFH–WAFH differences are slightly smaller before and slightly larger during COVID. We find no gender or WFH–WAFH differences in total work for childless men and women.

During COVID, in couples with one partner WFH, the partner WFH worked 1.3–1.5 fewer paid hours. When both were WFH, neither men nor women worked less than their WAFH counterparts. We find that women in dual-WFH couples worked 1.6 h longer per day than women WFH alone, which is 0.4 h longer than we found for mothers. When WFH alone relative to both WAFH, men did 1.8 h more household production and women did 1.3 h more household production, which is substantially larger than we found for parents. However, having a partner also WFH substantially reduced their household production time, with men and women spending 0.9–1.0 h less on these activities. This latter finding suggests that the gender gap in chores may be smaller in childless couples when they both WFH. Finally, we find no statistically significant differences in total work.

Thus, we find that among childless coupled men and women, the partner’s WFH status matters for both paid work and household production. The partner WFH alone substituted away from paid work to household production. However, if they both were WFH, men and women did not decrease their paid work and shared the increase in household responsibilities more equally.

6 Conclusion and discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in extraordinary demands on employed parents to increase household-provided childcare while trying to maintain their paid work hours. Some could do so because there was simultaneously a massive social experiment in WFH. Among dual-earner parents with children under age 13, we observe that 29.8% of fathers’ workdays and 39.5% of mothers’ workdays were WFH days between May 2020 and December 2021, a three-and-a-half-fold increase compared to the five years preceding the pandemic.

Using the 2015–2021 ATUS, we examined the gendered effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in the medium-run on time spent on paid work, chores, and caregiving by parents in dual-earner couples, and investigated how their weekday workday time allocation differed by the work location arrangements of the couple and by whether their child was at home during the workday. Mothers were primary caregivers prior to the pandemic. Our analyses for the post-lockdown period suggest that mothers and fathers picked up equal amounts of the extra childcare burden when WFH alone. Thus, when fathers were WFH alone and thus were more available to their children, the gender care gap decreased. Among dual-remotely working couples, mothers and fathers were able to share more equally the increase in childcare responsibilities brought about by the pandemic. On the average day, fathers and mothers WFH did equally more household chores, regardless of their partners’ WFH statuses; however, on the average school day, fathers, but not mothers, WFH alone spent more time on household chores compared to their counterparts WAFH. When mothers and fathers were WFH together, they maintained their paid work hours; however, when mothers were WFH alone, they worked 1.1 fewer paid hours on the average day, but not on the average school day, which implies that the average day results may be driven by those without summer childcare. The mother–father difference in overall work (paid and unpaid) increased for those WFH during the pandemic. Those WFH also had more overall work than those WAFH, but there were no differences by the partner’s WFH status.

When WFH, parents with children at home during the workday spent substantially more time on childcare than those without children at home, but most of the time was supervisory childcare with much of it done while working. When both were WFH, mothers whose children were at home rather than at school during the workday spent 1.7 h more face time with their children compared to fathers. In addition, mothers WFH alongside fathers spent more time working with children under their care than did fathers. Mothers WFH were also more likely to spread their working hours throughout the day, with breaks in between work episodes, and to be working in the evening, when their children may have been sleeping. These potential disruptions in mothers’ working time could have negatively affected their productivity in paid work (Adams-Prassl, 2021) and thus contributed to some of the continued exit of mothers from the labor force in 2021 (Heggeness & Suri, 2021), as multitasking and work interruptions have negative implications for mothers’ well-being (Offer & Schneider, 2011).

While an increase in the availability of remote jobs could increase mothers’ labor force attachment, our findings suggest that remote work policies may not help to close the gender care gap. Instead, the gap could rise, because women have expressed more interest in continuing to work entirely remotely post-pandemic than have men (Parker et al., 2020). However, the gender chores gap may fall if fathers WFH to a greater extent than they did before the pandemic. Fathers WFH also increase their time with children, which may have positive benefits for children and families (Caetano et al., 2019; Fiorini & Keane, 2014; Hsin & Felfe, 2014; Mangiavacchi et al., 2021). In addition, we find that even among dual-remotely-working couples, when children were at home, fathers WFH during the pandemic spent a lot more time with children and fathers WFH with a partner spent more time on household production, which may lead to fundamental changes in fathers’ time allocation in the post-pandemic period. Recent work by Stevenson (2021) suggests that fathers’ attitudes about desired work hours and care time may be changing.

Finally, we also looked at differences in hours spent on household production by couple’s joint WFH status for a sample of men and women in dual-earner couples without dependent children. During the pandemic, when WFH alone relative to both WAFH, childless men and women WFH did substantially more household production compared to fathers and mothers, perhaps because they did not have childcare responsibilities as well. When both members of the couple were WFH relative to both were WAFH, the WFH–WAFH gap in household production was larger for men than women, suggesting that men and women in childless couples may have more equally shared household responsibilities.

This analysis is not without limitations. Some of our potentially important results are imprecise due to the small sample size. In addition, this is a cross-sectional analysis with a single time diary collected for only one member of the couple, so we cannot measure the gender gaps in care and chores within households by the couple’s joint WFH status directly but must instead rely on our predictions regarding the partner’s work location and differences in averages. We also do not know the remote worker status of those who were interviewed about non-workdays, and thus we cannot determine how the total workload may have changed across the week by WFH status, though we do not see an increase in paid work on weekend days. In addition, we examine dual-earner couples with children during the COVID-19 pandemic, but many mothers left the labor force to care for their children (Albanesi & Kim, 2021; Bauer et al., 2021; Heggeness et al., 2021; Heggeness & Suri, 2021).Footnote 24 Finally, our results for parents may not be generalizable to WFH during “normal” times because many children were in virtual schooling.

Data availability

This paper uses the American Time Use Survey available at https://www.bls.gov/tus/data.htm and the COVID-19 Data from the Current Population Survey available at https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/time-series/demo/cps/cps-supp_cps-repwgt/cps-covid.html.

Code availability

All analyses were conducted using the statistical software package Stata, version 17. The code is available here: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6282646.

Notes

The CPS asks, “At any time in the LAST 4 WEEKS, did you telework or work at home for pay BECAUSE OF THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC?” Workers may have worked from home for reasons other than the pandemic, and about 4.3% of workers were home-based workers prior to the pandemic (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). As the pandemic progressed into 2021, the CPS COVID question captured less work from home than other surveys, such as the Real-time Population Survey and Google COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports, likely because many jobs had been converted to permanent remote/hybrid positions (see Bick et al., 2022).

Authors’ own calculations based on the ATUS (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022).

In the fall of the 2020–21 school year, 60% of students started in a virtual K–12 schooling environment, 22% in a hybrid schooling environment, and 18% attended in person only (Burbio, 2021). More students attended in person later in the fall, with 37% still virtual in November 2020 and February 2021, but schools gradually reopened after that. Using the NLSY97, Aughinbaugh and Rothstein (2022) find that in the spring of 2021, 66% of parents had a child in remote schooling.

Restrepo and Zeballos (2022) find that workers WFH spent less time socializing with others but more time relaxing and engaged in more leisure compared to those WFH prior to the pandemic.

Replication files are located at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6282646 (Pabilonia & Vernon, 2022a).

Using the 2010–2020 ATUS, Restrepo and Zeballos (2022) found that among dual-headed households, the gap in paid work hours between those WFH and WAFH decreased during the pandemic due to a large increase in working time among those WFH, but they did not examine gender differences in the gap.

Studying the effects of initial school closures on parents’ work arrangements in Japan, Yamamura and Tsustsui (2021) found that full-time employed mothers of primary school-aged children were more likely to WFH than fathers.

All ATUS interviews are conducted 2–5 months later, although most are interviewed 3 months later.

Own children in the ATUS include biological, adopted, and stepchildren.

Estimates are similar when looking at work on main jobs only as few parents have multiple jobs.

See Appendix Table 8 for more details on the construction of these time-use categories.

See Appendix Table 9 for marginal effects from the probit model.

Note that only the employment status and usual hours of the partner are collected in the ATUS, so for the predictions, we are using the partner’s CPS responses on occupation, union status, etc.

Comparing childcare hours between 2020 and 2021 diaries, we find that in 2020, mothers WFH spent 10.6 h caring for children while in 2021 they spent 9 h, and the difference was statistically significant.

McDermott and Hansen (2021) also found that workers on GitHub reallocated their work hours outside of traditional core business hours in the early stages of the pandemic, but more so men than women.

We reach the same conclusion if we examine children aged 6–12 only.

Although some parents do not participate in an activity on their random diary day (the majority do), we believe that most regularly participate in these broad activity categories; therefore, OLS generates unbiased estimates (Stewart 2013). See Table 2 for the percentage of non-zero values for each activity.

Choosing a value closer to one would increase the standard errors, given our small sample.

See Appendix Table 12 for estimated differences in several detailed household production categories. Pre-COVID, mothers WFH spent more time cooking, on housework, and shopping compared to those WAFH; during COVID, mothers WFH spent more time than those WAFH only on cooking. During both periods, fathers WFH spent more time on cooking and housework than fathers WAFH, with the WFH–WAFH gap in cooking being slightly larger in the pre-pandemic period.

As a sensitivity analysis, we estimated Eq. (2) for a sample of parents with children under age 18, i.e., we added parents with teenagers only. Results are similar, but mothers WFH spent statistically significantly less secondary time and face time with children when their partners were also WFH and fathers WFH spent less time on household production when their partners were also WFH (Appendix Table 13).

Del Boca et al. (2022) found that Italian mothers did more of the supervising of homeschooling than did fathers.

Using the ATUS time diaries, Stewart (2010) found that mothers of preschoolers working part-time tend to shift their work schedules to later in the day so they can maximize their time in enriching child-care activities at times most appropriate for child development.

However, we note that Lyttelton et al. (2022a) who also studies changes in time use by work location and parental gender due to the pandemic does not find that including recent job leavers who may have selected out of work changes conclusions about differences in time spent on unpaid work and care actitivies by work location.

References

Adams-Prassl, A. (2021). The gender wage gap in an online labour market: The cost of interruptions. University of Oxford Department of Economics Discussion Paper Series No. 944. https://www.economics.ox.ac.uk/publication/1191577/hyrax.

Adams-Prassl, A., Boneva, T., Golin, M., & Rauh, C. (2020). Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: Evidence from real time surveys. Journal of Public Economics, 189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104245.

Aguiar, M., Hurst, E., & Karabarbounis, L. (2013). Time use during the great recession. American Economic Review, 103(5), 1664–1696. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.5.1664.

Albanesi, S., & Kim, J. (2021). Effects of the COVID-19 recession on the U.S. labor market: Occupation, family, and gender. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 35(3), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.35.3.3.

Alon, T. M., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J., & Tertilt, M. (2020a). The impact of COVID-19 on gender equality. Covid Economics: Vetted and Real-Time Papers, 4, 62–85. https://cepr.org/sites/default/fles/news/CovidEconomics4.pdf.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., Marcen, M., Morales, M, & Sevilla, A. (2022). Schooling and parental labor supply: Evidence from COVID-19 school closures in the United States. ILR Review https://doi.org/10.1177/00197939221099184.

Aughinbaugh, A. & Rothstein, D. R. (2022). How did employment change during the COVID-19 pandemic? Evidence from a new BLS survey supplement. Beyond the Numbers: Employment and Unemployment, 11(1), U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/volume-11/how-did-employment-change-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.htm.