Abstract

In this paper we disentangle the impact of household financial constraints on mortgage rate from a number of dimensions of credit risk. This analysis relies on a dataset that contains information on the economic and financial decisions of Spanish households in four different years: 2002, 2005, 2008, and 2011. Our results suggest that banks’ profitable customers are able to bargain for lower mortgage rates. However, contrary to other studies, the risk profile does not have a significant effect on mortgage rates. Credit institutions tend to charge higher rates during the crisis to all customers, irrespective of their risk profiles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In addition, households have different likelihoods of being selected for the survey, given the overrepresentation of the wealthiest households and the geographic stratification. For this reason, the survey contains weights for each household that are necessary in order to obtain descriptive statistics for the population. Nevertheless, following Rosenthal (2002), to estimate the models proposed in this study we assign the same weights to each observation of the corresponding subsample.

The customer profitability measures in our study cannot directly capture the extent to which those profits come from cross-selling opportunities. However, we hypothesize that this cross-selling to customers represents potential profitable opportunities for the bank. In fact, it is very common in Spain for the bank granting the mortgage to typically offer interest rate discounts (or other benefits associated with the mortgage) to their already existing or new customers if these clients already hold or purchase other (fee-oriented) products from the bank (i.e., credit and debit cards, saving accounts, pension funds, mutual funds, insurances,...).

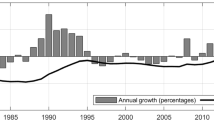

Interest rates are obtained from the European Central Bank statistics on the monetary financial institution (MFI) sector.

See “Guía de Acceso al Préstamo Hipotecario” (Bank of Spain): http://www.bde.es/bde/es/secciones/informes/Folletos/guia_de_acceso_a/

See the webpage on financial education developed by the Central Bank of Spain and the Securities and Exchange Commission (Finanzas para Todos): http://www.finanzasparatodos.es/es/economiavida/comprandovivienda/compraroalquilar.html

The standard deviations of dummy variables are not reported as they are meaningless.

Note that the use of LTV equal to or greater than 100% implies that the wealth constraint cannot be used in our analysis.

See “Guía de Acceso al Préstamo Hipotecario” (Bank of Spain): http://www.bde.es/bde/es/secciones/informes/Folletos/guia_de_acceso_a/

References

Agarwal, S., Chomsisengphet, S., Liu, C., and Souleles, N. S. (2010). Benefits of relationship banking: evidence from consumer credit markets. Working Paper Series: WP-2010-05. Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

Allen, J., Clark, C. R., & Houde, J. F. (2014). Price dispersion in mortgage markets. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 62, 377–416.

Ampudia, M., and Mayordomo, S. (2015). Borrowing constraints and housing price expectations in the Euro area. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2657176

Barakova, I., Bostic, R. W., Calem, P. S., & Wachter, S. M. (2003). Does credit quality matter for homeownership? Journal of Housing Economics, 12, 318–336.

Barakova, I., Calem, P. S., & Wachter, S. M. (2014). Borrowing constraints during the housing bubble. Journal of Housing Economics, 24, 4–20.

Beck, T., Büyükkarabacak, B., Rioja, F., and Valev, N. (2012). Who gets the credit? And does it matter? Household vs firm lending across countries. B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics, 12(1), 1–46.

Bourassa, S. C. (2000). Ethnicity, endogeneity, and housing tenure choice. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 20, 323–341.

Bourassa, S. C., & Hoesli, M. (2010). Why do the Swiss rent? Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 40, 286–309.

Brown, M., and Hoffmann, M. (2013). Mortgage relationships. Working Paper No. 1310 University of St. Gallen.

Bucks B. K., Kennickell, A. B., Mach, T. L., and Moore, K. B. (2009). Changes in U.S. family finances from 2004 to 2007: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances. Federal Reserve Bulletin (February), A1-A56.

Calem, P. S., Firestone, S., & Wachter, S. M. (2010). Credit impairment and housing tenure status. Journal of Housing Economics, 19, 219–232.

Chiang, R. C., Chow, Y. F., & Liu, M. (2002). Residential mortgage lending and borrower risk: the relationship between mortgage spreads and individual characteristics. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 25, 5–32.

Crespi, R., García-Cestona, M. A., & Salas, V. (2004). Governance mechanisms in Spanish banks. Does ownership matter? Journal of Banking & Finance, 28, 2311–2330.

Diaz-Serrano, L. (2005). On the negative relationship between labor income uncertainty and homeownership: risk-aversion vs. credit constraints. Journal of Housing Economics, 14, 109–126.

Duca, J. V., & Rosenthal, S. S. (1993). Borrowing constraints, household debt, and racial discrimination in loan markets. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 3, 77–103.

Duca, J. V., & Rosenthal, S. S. (1994a). Borrowing constraints and access to owner-occupied housing. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 24, 301–322.

Duca, J. V., & Rosenthal, S. S. (1994b). Do mortgage rates vary based on household default characteristics? Evidence on rate sorting and credit rationing. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 8, 99–113.

Edelberg, W. (2006). Risk-based pricing of interest rates for consumer loans. Journal of Monetary Economics, 53, 2283–2298.

Einav, L., Jenkins, M., & Levin, J. (2013). The impact of credit scoring on consumer lending. The Rand Journal of Economics, 44, 249–274.

European Central Bank (2013). The Euro system household finance and consumption survey: Results from the first wave. Statistics Paper Series No. 2.

Haurin, D. R., Hendershott, P. H., & Wachter, S. M. (1996). Wealth accumulation and housing choices of young households: an exploratory investigation. Journal of Housing Research, 7, 33–57.

Haurin, D. R., Hendershott, P. H., & Wachter, S. M. (1997). Borrowing constraints and the tenure choice of young households. Journal of Housing Research, 8, 137–154.

Holmes, J., Isham, J., Petersen, R., & Sommers, P. M. (2007). Does relationship lending still matter in the consumer banking sector? Evidence from the automobile loan market. Social Science Quarterly, 88, 585–597.

Keys, B. J., Mukherjee, T., Seru, A., & Vig, V. (2010). Did securitization lead to lax screening? Evidence from subprime loans. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125, 307–362.

Lago-González, R., and Salas-Fumás, V. (2005), Market power and bank interest rate adjustments, Bank of Spain Working Paper no. 0539.

Linneman, P., & Wachter, S. (1989). The impacts of borrowing constraints on homeownership. The Journal of the American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association, 17, 389–402.

Linneman, P., Megbolugbe, I. F., Wachter, S., & Cho, M. (1997). Do borrowing constraints change U.S. homeownership rates? Journal of Housing Economics, 6, 318–333.

Magri, S., & Pico, R. (2011). The rise of risk-based pricing of mortgage interest rates in Italy. Journal of Banking & Finance, 35, 1277–1290.

Maudos, J., Pastor, J. M., & Pérez, F. (2002). Competition and efficiency in the Spanish banking sector: the importance of specialization. Applied Financial Economics, 12, 505–516.

Puri, M., Rocholl, J., & Steffen, S. (2011). Global retail lending in the aftermath of the US financial crisis: distinguishing between supply and demand effects. Journal of Financial Economics, 100, 556–578.

Rosenthal, S.S., (2002). Eliminating credit barriers: how far can we go? In: Retsinas, N.P. (Ed.), Low-income Homeownership: Examining the Unexamined Goal.

Rubin, D. B. (1987). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: Wiley.

Tsai, M. S., Liao, S. Z., & Chiang, S. L. (2009). Analyzing yield, duration and convexity of mortgage loans under prepayment and default risks. Journal of Housing Economics, 18, 92–103.

Van Leuvensteijn, M., Bikker, J. A., van Rixtel, A., & Kok Sørensen, C. (2011). A new approach to measuring competition in the loan markets of the euro area. Applied Economics, 43, 3155–3167.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from FUNCAS Foundation, MICINN-FEDER ECO2015-67656-P and ECO2014-59584 and Junta de Andalucía P12.SEJ.2463 (Excellence Groups) is gratefully acknowledged by Santiago Carbo-Valverde and Francisco Rodriguez-Fernandez. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily coincide with those of the Banco de España and the Eurosystem.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Definition of Variables

Appendix: Definition of Variables

The control variables used in our analysis are created as follows:

Household Income

The EFF provides the household income in the year of survey. To obtain the desired home value we need the household income for the year in which the home was purchased. We obtain the income for that year by discounting the income by the inflation. This is equivalent to assuming that the income increases at the same rate as inflation does.

Household Net and Gross Wealth

The household gross wealth is obtained as the sum of the value of financial assets (listed and non-listed stocks, mutual funds, pension funds, life insurance, bank time deposits and other financial assets) and real assets (principal residence, other real estate properties, jewelry, art, and own business, in the event that they run a business) held by the household. The net wealth is defined as the total wealth minus the household’s total debt.

To obtain the desired home value we use the net wealth in the year in which the household purchased the home. This is calculated as the gross wealth minus the change in the housing value and the total savings over the period spanning from the home purchase date to the survey date.

Other Household Characteristics

Among the household characteristics affecting the desired home value or the mortgage rates:

-

Education: three dummy variables indicating whether the highest level of education of the person of reference is obtained at primary school, high school, or university.

-

Age of the person of reference and age-squared.

-

Number of family members.

-

Number of adults working.

-

Rural/urban area: dummy variables constructed on the basis of the economic sector in which the activities of the person of reference take place: primary, secondary, or tertiary sector, under the assumption that those households in which the person of reference works in the primary (secondary or tertiary) sector live in a rural (urban) area.

-

Gender: dummy variables for the gender of the person of reference.

-

Year of move: dummy variables indicating the year in which the household purchased/rented their current home.

-

Marital status: four dummy variables indicating whether the person of reference is single, married or in a consensual union with legal basis, widowed, or divorced.

-

Labor situation: four dummy variables indicating whether the person of reference is employed, self-employed, retired, or unemployed.

All the previous variables are employed to obtain the desired housing value, where the variables are defined in terms of the year in which the household purchased the home. We impute the value of the variables at the purchase year as follows. The education, number of family members, number of working adults, rural or urban area proxy, gender, marital status and labor situation are assumed to remain unchanged between the year in which the home is purchased and the survey date. This imputation method seems reasonable given that the maximum distance between the two events is 3 years. Given that the survey contains the year of birth of the person of reference, we can easily calculate his/her age at the year of purchase.

Credit Scoring

The survey does not contain information on the credit scoring. We propose a simple measure of this scoring following the advice of financial institutions on the dimensions and practices considered to define this scoring and the set of variables proposed in the access-to-mortgage guide elaborated by the Central Bank of Spain to define the credit history.Footnote 8 This measure of scoring is adapted to the variables contained in the EFF. Our aim is to create a credit scoring indicator on the basis of the main information used by banks to evaluate the process of mortgage granting. The scoring is a weighted average of three dimensions that refer to the household capacity for payment (with the weights shown in brackets): (i) payment and capital capacity (50%), (ii) household characteristics and payment history (30%), and (iii) characteristics of other household debts (20%). Each category consists of several subcategories with different weights and scores as follows:

-

Payment and capital capacity (50%):

-

Ratio of liquid assets to income: LI (50%)

-

If LI > 0.75 then scoring =25.

-

If LI > 0.5 and LI ≤ 0.75 then scoring =18.75.

-

If LI > 0.25 and LI ≤ 0.5 then scoring =12.5.

-

If LI ≤ 0.25 then scoring =6.25.

-

-

Ratio of total debt relative to labor income: DL (30%)

-

If DL < 2 then scoring =15.

-

If DL ≥ 2 and DL < 4 then scoring =11.25.

-

If DL ≥ 4 and DL < 6 then scoring =7.5.

-

If DL ≥ 6 then scoring =3.75.

-

-

Ratio of total debt relative to total gross wealth: DW (20%)

-

If DW ≤ 0.25 then scoring =10.

-

If DW > 0.25 and DW ≤ 0.5 then scoring =7.5.

-

If DW > 0.5 and DW ≤ 0.75 then scoring =5.

-

If DW > 0.75 then scoring =2.5.

-

-

-

Household characteristics (30%):

-

The person of reference in the household is married or in a domestic partnership (15%)

-

If yes then scoring =4.5, otherwise scoring =0.

-

-

The household has other real assets that could be used as guarantee (15%)

-

If yes then scoring =4.5, otherwise scoring =0.

-

-

There is a civil servant among the household members (35%)

-

If yes then scoring =10.5, otherwise scoring =0.

-

-

At least two people living in the household are employed (35%)

-

If yes then scoring =10.5, otherwise scoring =0.

-

-

-

Characteristics of other household debts (20%):

-

Time-to-maturity of the mortgage: TM (70%)

-

If TM > 20 then scoring =14.

-

If TM ≥ 10 and TM < 20 then scoring =10.5.

-

If TM ≥ 5 and TM < 10 then scoring =5.25.

-

If TM < 5 then scoring =1.3124.

-

-

The household uses several loans for the house purchase (30%)

-

If yes then scoring =6, otherwise scoring =0.

-

-

The scoring indicator is defined such that the higher the scoring obtained, the greater the risk. The measure is between 0 (lowest risk) and 100 (highest risk).

Customer Profitability

We consider two categories depending on the banking business to which they refer in order to define profitable customers: fee-oriented activities or asset management activities. Fee-oriented activities are: (i) the use of credit cards, (ii) use of electronic payments, (iii) use of checks, (iv) use of direct billing or direct deposits, and (v) use of telephone and internet banking. Asset management activities include: (a) holdings of mutual funds, (b) holdings of life insurance, and (c) holdings of pension funds. For each of the eight total categories referring to the use of a given service or the holding of a given asset, we define a dummy variable that takes on a value of 1 in cases where the household uses the corresponding service or holds the corresponding asset, and a value of 0 otherwise. To define the variable referred to total profitability, we total the values obtained for the 8 dummy categories so that a household that uses all services and holds all three types of assets will be assigned a value of 8, whereas the minimum value that can be obtained is zero. We later distinguish the degree of profitability in relation to fee-oriented activities by totaling the values of the five dummy variables (i) to (v), so that the resulting variable value ranges between 0 and 5. Finally, in order to obtain the degree of profitability in relation to asset management activities, we total the values of the three dummy variables (a) to (c) so that the resulting variable value ranges between 0 and 3.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carbó-Valverde, S., Mayordomo, S. & Rodríguez-Fernández, F. Disentangling the Effects of Household Financial Constraints and Risk Profile on Mortgage Rates. J Real Estate Finan Econ 56, 76–100 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-016-9595-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-016-9595-7