Abstract

We analyze property subsidiary sell-offs in China to examine her market reaction to firms’ divestiture decisions. Overall, the response from the stock market is neutral. However, detailed analysis reveals that the market reacts differently to property subsidiary sell-off announcements by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and non-SOEs. Consistent with findings from extant literature, we find statistically positive market returns associated with non-SOE sell-off announcements. However, we find statistically negative market returns associated with SOE sell-off announcements. We suggest that this divergent market reaction is influenced by the institutional feature of the Chinese market and is consistent with the high agency costs associated with state ownership.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The asset valuation hypothesis maintains that because the book value of real estate assets are usually lower than its market value, analysts and investors will react favorably when the property is sold at a price higher than its book value. The tax shield hypothesis posits that the sale of a mature (fully depreciated) property and subsequent purchase of a replacement property allows firms to increase the size of their tax shelter. The synergies hypothesis argues that the sold property is not asset allocation efficient for the firm, or that the real estate arm of the business generates a negative synergy with the parent firm. Rodriguez and Sirmans (1996) and Campbell (2002) provide excellent and detailed reviews of the literature related to real estate sell-offs.

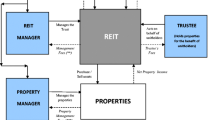

Campbell et al. (2006) argue that neither the undervaluation nor the depreciation tax shield arguments applies well to the case of REITs. First, analysts are unlikely to underestimate property assets in the same way as conventional firms. Second, REITs also do not pay corporate taxes. The authors find a negative relationship between shareholder returns and sell-offs that is primarily motivated by debt reduction. They also argue that in an asymmetric information environment, managers who choose to increase a firm’s leverage are sending signals indicating confidence of future cash flows.

Agency costs comprise monitoring expenses (formal audits, budget restrictions, incentive-compatible compensation policies, operating rules, etc.) incurred by the principal, bonding expenses (contractual guarantees and limitations) incurred by the agent, and residual costs arising from a divergence in the decisions made by the agents that do not maximize the principal’s welfare.

According to Shleifer and Vishny (1989), managers tend to acquire assets which require their expertise to manage; thus, putting them in a valuable and difficult-to-replace position in the firm. As a result, investment opportunities that generate higher NPV returns may be rejected to make way for manager-specific projects.

In October 1993, the 14th Congress of Communist Party of China introduced reforms towards the establishment of a socialist market economy with Chinese characteristics. The 15th Congress further identified public ownership as the mainstay of the economy, with diverse forms of ownership to develop side by side.

Another form of government ownership of the shares can be in the form of legal-person shares. These are shares owned by business agencies or local enterprises that are partially owned by the central or local government. Prior to 2004, shares owned by the state and legal-person shares are not tradable on the stock exchanges. However, in early 2004, the State Council promulgated the ‘Guidelines on Promoting Reform, Opening Up and Steady Development of the Capital Market’. Consequently, in 2005–2006, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) implemented reforms to lift the trading ban on non-tradable shares for ‘well-functioning market infrastructures and orderly operations’ (CSRC 2007).

Three examples of state policy related issues faced by SOEs are: (i) SOEs are instructed to operate in capital-intensive industries; (ii) SOEs have to pay wages, pensions and other social-welfare benefits of their current, redundant as well as retired workers; and (iii) some SOEs’ output prices are still distorted (artificially suppressed) below production costs. In their paper, Lin et al. (1998) argue that the key for a successful reform is to create a level playing field by removing these policy burdens on the SOEs.

Chinese media reported that in 2012, the amount of government subsidies granted to the top ten listed SOEs was comparable to the sum of net profits of all listed firms in the SZSE ChiNext. (Source: http://ccnews.people.com.cn/n/2013/0502/c141677-21336993.html). China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) reported a government subsidy of 9.4 billion RMB in their 2012 financial statement. (Source: http://www.cninfo.com.cn/finalpage/2013-03-22/62239965.PDF?www.cninfo.com.cn.). Based on annual reports for 2012, “business entertainment” expenses by listed firms in China totalled 13.3 billion RMB, while the “business entertainment” expenses by the top ten SOEs was 2.9 billion RMB. (Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/zhongwen/simp/china/2013/05/130514_china_statecompanies.shtml.)

The factors include: (i) presence of a dominant shareholder; (ii) the trading of state and legal persons shares are highly restricted, therefore encouraging the controlling stakeholder to obtain benefits from other channels rather than price appreciation in the shares; (iii) minority shareholders have limited legal enforcement rights against the controlling shareholders; and (iv) security market regulators have limited authority to enforce fines and prison terms for tunneling.

This approach assumes cross-sectional independence of stock returns during each firm’s estimation period and event period.

Prior to 1 January 2007, the Chinese Accounting Standards (CAS), which was designed for financial reporting in a centrally planned economy with the state as the sole owner of the industry, was not suitable for reporting company’s performance in a market economy. From January 2007, China’s Ministry of Finance announced the adoption of 39 standards that are substantially aligned with the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRSs) set by the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). Source: Release Ceremony for Chinese Accounting Standards System and Audition Standards System held in Beijing. Retrieved from http://www.acga-asia.org/public/files/China_New_Accounting_Sytem_Feb06.pdf.

Shanghai Stock Exchange (SHSE) and Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE) are China’s two national stock exchanges: SHSE was re-established in December 1990, while SZSE was established in April 1991. As at Jun 2012, the SHSE had a total market capitalization of 15.3 trillion renminbi (RMB) with 945 company listings. The SZSE had a total market capitalization of 7.2 trillion RMB with 1482 company listings on its main board. (Source: SHSE http://www.sse.com.cn; SZSE http://www.szse.cn). The SZSE also has a SME board and ChiNext (growth enterprise board). The firms listed with these two boards are smaller firms with high growth potential, mainly in the high-tech industries like bio-technology, new energy, information technology and modern services, etc.

These firm announcements and the exact date of the announcements can be accessed through the official websites of the two stock exchanges.

On April 22, 1998, the two stock exchanges announced that special treatment is to be given to listed companies with abnormal financial conditions. These are: (i) negative net profit over two consecutive fiscal years; (ii) the per share net assets in a recent fiscal year is lower than the face value of the share; (iii) no audit report from an authorized accounting firm; and (iv) abnormal financial behavior identified and claimed by China Securities Regulatory Commission or a Stock Exchange. Source: China Stock Market Handbook (2008, February 15). Retrieved from http://my.safaribooksonline.com/book/international-business-globalization/9781602670068/key-concept-of-china-stock-markets/par01ch04sec04.

There are two types of share listings – A and B – on the mainboards of the stock exchange in China. ‘A’ type shares are denominated in Chinese RMB and are traded by Chinese residents (exclude residents in Hong Kong and Macau, and also the residents in Taiwan), Chinese domestic organizations/institutions and qualified foreign institutional investors. ‘B′ type shares are denominated in foreign currency (USD in the SHSE and HKD in the SZSE) and are open to trading by both domestic and foreign investors.

Prior to 2005, the percentage of tradable shares/total outstanding shares in China’s securities market is 38 %. Thereafter, with the lifting of the non-tradable shares, the percentages increase steadily, and for our period of study: 2007–46 %; 2008–51 %, 2009–75 %, 2010–77 %; 2011–80 % and 2012–82 %. (Source: CSRC Annual Report 2012, http://www.csrc.gov.cn/pub/csrc_en/Informations/publication/201307/ P020130716578944216513.pdf).

Two examples are: (i) Zhuhai Port Co., Ltd. which sold off their real estate subsidiary for 36 million RMB on 23 November 2010 and announced that it is retreating from real estate to focus on its port logistic business (http://www.cninfo.com.cn/finalpage/2010-11-23/58693768.PDF?www.cninfo.com.cn), and (ii) Yeland Group Co., Ltd. which sold 50 % of their real estate subsidiary for 270 million RMB on 12 February 2010. The firm announced that the divestiture was strategically taken to reinforce the high-end positioning of its brand. (http://www.cninfo.com.cn/finalpage/2010-02-12/57607069.PDF?www.cninfo.com.cn)

On 7th January 2010, the State Council of China announced a series of measures designed to cool down China’s property market. These measures include: requiring banks to set loan quota and enhance credit management for developers, imposing a 40 % down payment for buyers of second properties, allowing local governments to restrict property purchases from migrants. On 17th April 2010, more measures were announced: the down payment is now increased to 50 % of the property value, buyers of second properties have to pay 1.1 times the bench mark loan rate, banks can no longer lend to buyers of third properties, and property purchase restrictions were imposed in 12 cities. On 1 January 2011, more measures were announced: the down-payment is raised further to 60 % of property price, and property purchase restrictions are now imposed in all municipalities, provincial capitals, and cities with high housing prices. (Source: State Council Files 2010(4), 2010(10), and 2011(1)). One example is Anhui Shan Ying Paper Industry Co., Ltd., which sold 51 % of its real estate subsidiary for 61 million RMB in September 2010 to avoid excessive risk exposure to the real estate market that was affected by the government cooling measures. (Source: http://www.cninfo.com.cn/finalpage/2010-07-10/58156093.PDF?www.cninfo.com.cn.)

An example is Shaanxi International Trust & Investment Co., Ltd. which sold 100 % of its real estate subsidiary for 95 million RMB in March 2011 in response to the China Banking Regulatory Commission’s regulatory policy to promote restructuring and development of specialized financial institutions. (Source: http://www.cninfo.com.cn/finalpage/2011-03-12/59111741.PDF?www.cninfo.com.cn.)

A case example of this would be Xiamen Insight Investment Co., Ltd. which sold 65 % of their real estate subsidiary for 19.6 million RMB in 2010 due to the subsidiary’s poor performance (http://www.cninfo.com.cn/finalpage/2010-01-04/57461600.PDF?www.cninfo.com.cn).

Since the introduction of the new Chinese Accounting Standards on 1 Jan. 2007, firms are required to make public any related party transaction and its value. According to the new standards, a related party transaction occurs, “when a party controls, jointly controls or exercises significant influence over another party, or when two or more parties are under the control, joint control or significant influence of the same party, the affiliated party relationships are constituted.” This new definition broadened “related party transaction” to include dealings with the firm managers and their close family members.

One serious incidence associated with related-party transaction was the D’Long Crisis in April 2004. D’Long was once the largest conglomerate in China. Listed subsidiaries of D’Long were manipulated to obtain bank loans, the proceeds of which were later channelled to other non-listed sector of the D’Long group through complicated RPTs. D’Long also constructed a network of loan-guarantee among seemingly unrelated firms which were in fact under the control of D’Long through complicated ownership structures. The incidence escalated into a credit crisis when commercial banks and brokerage firms announced they were mired in the D’Long’s chain of bad loans.

In total, we ran 21 regressions to test the interaction terms (7 agency-related variables) for intervals (−1, 0) (−1, −1) and (3, 17).

The tables of the regression results are not reported here, but are available on request.

China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation/ Zhongguo Shihua, listed on Shanghati Stock Exchange (firm code: 600,028)

Nanjing Xinjiekou Department Store Co., Ltd., listed on Shanghai stock exchange (firm code: 600,682)

References

Alexander, G. J., Benson, P. G., & Kampmeyer, J. M. (1984). Investigating the valuation effects of announcements of voluntary corporate selloffs. Journal of Finance, 39(2), 503–517.

Ambrose, B. W. (1990). Corporate real estate’s impact on takeover market. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 3, 307–322.

Bates, T. W. (2005). Asset sales, investment opportunities, and the use of proceeds. Journal of Finance, 80(1), 105–134.

Boudreaux, K. J. (1975). Divestiture and share price. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 10(4), 619–626.

Campbell, R. D. (2002). Shareholder wealth effects in equity REIT restructuring transactions: sell-offs, mergers and joint ventures. Journal of Real Estate Literature, 10(2), 205–222.

Campbell, R. D., Petrova, M., & Sirmans, C. F. (2006). Value creation in REIT property sell-offs. Real Estate Economics, 34(2), 329–342.

China Securities Regulatory Commission. (2007). China’s securities and futures markets. Retrieved from http://www.csrc.gov.cn/pub/csrc_en/Informations/publication/200812/P020090225568827507 804.pdf.

Conyon, M. J., & He, L. (2011). Executive compensation and corporate governance in China. Journal of Corporate Finance, 17, 1158–1175.

Deng, Y., Morck, R., Wu, J., & Yeung, B. (2011). Monetary and fiscal stimuli, ownership structure, and China’s housing market. NBER Working Paper Series, Working Paper 16871. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w16871.

Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. C. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 301–325.

Fan, J. P. H., Wong, T. J., & Zhang, T. Y. (2007). Politically connected CEOs, corporate governance, and post-IPO performance of China’s newly partially privatized firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 84, 330–357.

Gaughan, P.A. (2011). Mergers, acquisitions, and corporate restructurings. John Willey&Sons/Hoboken-New Jersey, fifth edition.

Glascock, J. L., Davidson, W. N., & Sirmans, C. F. (1989). An analysis of the acquisition and disposition of real estate assets. Journal of Real Estate Research, 4(3), 131–140.

Glascock, J. L., Davidson, W. N., & Sirmans, C. F. (1991). The gains from corporate sell-offs: the case of real estate assets. AREUEA Journal, 19(4), 567–582.

Hanson, R. C., & Song, M. H. (2000). Managerial ownership, board structure, and the division of gains in divestitures. Journal of Corporate Finance, 6, 55–70.

Hearth, D., & Zaima, J. K. (1984). Voluntary corporate divestitures and value. Financial Management, 13(1), 10–16.

Hirschey, M., & Zaima, J. K. (1989). Insider trading, ownership structure, and the market assessment of corporate sell-offs. Journal of Finance, 44(4), 971–980.

Hite, G. L., Owers, J. E., & Rogers, R. C. (1987). The market for interfirm asset sales: partial sell-offs and total liquidations. Journal of Financial Economics, 18, 229–252.

Jain, P. C. (1985). The effect of voluntary sell-off announcements on shareholder wealth. Journal of Finance, 40(1), 209–224.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 305–360.

Jiang, G. H., Lee, C. M. C., & Yue, H. (2010). Tunneling through intercorporate loans: the China experience. Journal of Financial Economics, 98, 1–20.

John, K., & Ofek, E. (1995). Asset sales and increase in focus. Journal of Financial Economics, 37, 105–126.

Klein, A. (1986). The timing and substance of divestiture announcements: individual, simultaneous and cumulative effects. Journal of Finance, 41(3), 685–696.

Lang, L., Poulsen, A., & Stulz, R. (1995). Asset sales, firm performance, and the agency costs of managerial discretion. Journal of Financial Economics, 37, 3–37.

Lin, J. Y. F., Cai, F., & Li, Z. (1998). Competition, policy burdens, and state-owned enterprise reform. American Economic Review, 88(2), 422–427.

Ma, S. (2004). The efficiency of China’s stock market. UK: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Patell, J. (1976). Corporate forecasts of earnings per share and stock price behavior: empirical tests. Journal of Accounting Research, 14(2), 246–276.

Perotti, E. C. (1995). Credible privatization. American Economic Review, 85(4), 847–859.

Pike, R., & Neale, B. (2009). Corporate finance and investment – decisions and strategies. FT Prentice Hall: Sixth edition.

Qu, Q. (2003). Corporate governance and state-owned shares in China listed companies. Journal of Asian Economics, 14, 771–783.

Rodriguez, M., & Sirmans, C. F. (1996). Managing corporate real estate: evidence from the capital markets. Journal of Real Estate Literature, 4(1), 13–33.

Rosenfeld, J. D. (1984). Additional evidence on the relation between divestiture announcements and shareholder wealth. Journal of Finance, 39(5), 1437–1448.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1989). Management entrenchment, the case of manger-specific investment. Journal of Financial Economics, 25, 123–139.

Sun, Q., & Tong, W. H. S. (2003). China share issue privatization: the extent of its success. Journal of Financial Economics, 70(2), 183–222.

Szamosszegi, A., & Kyle, C. (2011). An analysis of state-owned enterprises and state capitalism in China. US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, October 26, 2011. Retrieved from https://thinksheetchina3.com/Research/Interest Group Library/SOE Study.pdf.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the valuable comments and suggestions from Siqi Zheng, Simon Stevenson, Seow Eng Ong, Dogan Tirtiroglu, Bill Hardin, Zhonghua Wu and participants at the Asian Pacific Real Estate Research Symposium 2013 and Akinsomi Omokolade Ayodeji and participants at the American Real Estate Society Conference 2014, San Diego, USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

In property subsidiary sell-offs, where there are transaction parties (buyer and seller) and cash settlements, this business environment is conducive to self-dealing or tunnelling by managers. We report agency conflicts in two cases of property subsidiary divestitures in China

-

Case 1: Chen Tonghai, the former GM and Chairman of the board of CPCCFootnote 28 received life sentence with a two-year reprieve for bribery of 195.73 million CNY. In year 2004, CPCC sold 75 % share of Taishan Real Estate Co., Ltd., a second-tier subsidiary, to Shouchuang Investment Co., Ltd. for 123.36 million CNY. The interesting story is that only two months later, Shouchuang Investment resold Taishan Real Estate to another party, but for 325.50 million CNY. And around 200 million were lost by CPCC. Investigations revealed that the owner of Shouchuang Investment was the mistress of Chen.

-

Case 2: During 2006 and 2007, NJXBFootnote 29 sold 100 % shares of a real estate subsidiary, Zhujiang NO.1 Real Estate Development Co., Ltd., to a private company named Xinpeng Real Estate Development for 128.79 million CNY. The buyer was claimed to be an unrelated party. NJXB received 128.79 million and made accounting profit of 35 million in the process. This divestiture did not arouse suspicion until 23th march 2009, when an announcement by NJXB let the cat out of the bag. The announcement revealed an acquisition plan to solve the intra-industry competition between NJXB and its holding company, Golden Eagle Group Co., Ltd. The acquisition package includes repurchasing the 100 % shares of Zhujiang NO.1, which was originally owned by NJXB. In less than three years, the price for the 100 % shares of Zhujiang NO.1 jumped from 128.79 million to 1635 million without substantive changes in its assets. Chances are that NJXB sold Zhujiang NO.1 for less than its value in 2006 and 2007, even though 35 million accounting profit was realized. Another doubt is how Zhujiang NO.1 became an asset of Golden Eagle Group. A rectification notice by China Securities Regulatory Commission solved the mystery: Both Xinpeng Real Estate and NJXB were controlled by the same person who also chairs the Golden Eagle Group. NJXB concealed the identity of Xinpeng Real Estate as a related party in 2006 and 2007.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, R., Chow, Y.L. & Ooi, J.T. A Relook into the Impact of Divestitures in the Presence of Agency Conflicts: Evidence from Property Subsidiary Sell-Offs in China. J Real Estate Finan Econ 55, 313–344 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-016-9584-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-016-9584-x