Abstract

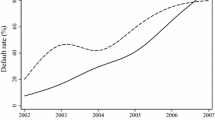

Subordination is designed to provide credit risk protection for senior CMBS tranches by allocating the initial credit losses to the more junior tranches. Subordination level should in theory reflect the underlying credit risk of the CMBS pool. In this paper, we test the hypothesis that subordination is purely about credit risk as intended. We find a very weak relation between subordination levels and both the ex post and ex ante measures of credit risk, rejecting our null-hypothesis. Alternatively, we find that subordination levels were driven by non-credit risk factors, including supply and demand factors, deal complexity, issuer incentive and a general time trend. We conclude that contrary to the traditional view, the subordination level is not just a function of credit risk. Instead it also reflects the market need of a certain deal structure and is influenced by the balance of power among issuers, CRAs and investors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In addition to a signaling effect, credit ratings may provide valuable regulatory arbitrage opportunities to certain investors (Stanton and Wallace 2012).

Some unrated tranches are also issued in many CMBS deals.

We carefully match the time window on which we calculate deal loss with the duration of the tranche (AAA or BBB) that we analyze to make sure the cumulative default loss of the CMBS deal is in fact the risk bared by a particular tranche.

The loans could be bought from traditional lenders, portfolio holders or from conduit loan originators.

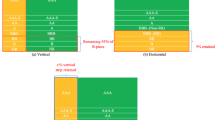

This type of structure is often referred to as the “reverse waterfall” structure.

It is noteworthy that some CMBS deals vary from this simple structure. For more information, see An and Vandell (2013). Also see Geltner and Miller (2001) for other issues such as commercial mortgage underwriting, form of the trust, servicing, commercial loan evaluation, etc.

Many CMBS deals also have an interest only (IO) tranche, which absorbs excess interest payment.

Throughout the paper, we use the S&P and Fitch rating scale (e.g., AAA). Moody’s ratings (e.g., Aaa) are mapped into their S&P/Fitch equivalents.

Moody’s, Standard and Poor’s and Fitch are currently three major CMBS rating agencies. There are other smaller CRAs such as Kroll Bond Ratings, and Realpoint that rate CMBS. Duff & Phelps Credit Rating Co. was another CRA that rated CMBS before Fitch acquired them.

CRAs also provide surveillance services, i.e., they monitor each CMBS bond after its issuance, and like in corporate bond market, they upgrade and downgrade some bonds according to the change in the CMBS pool performance.

CRAs usually apply “haircuts” to loan underwriting NOI.

For example, Moody’s uses a stabilized cap rate to try to achieve a “through-the-cycle” property value.

Although rating agencies perform property and loan analysis mainly on individual basis, they sometimes only review a random sample (40–60 %) of the loans when number of mortgages in the pool is large, the pool was originated with uniform underwriting standards and the distribution of the loan balance is not widely skewed.

CMAlert does not provide on-time CMBS performance data.

We exclude government agency deals and deals backed by commercial real estate leases.

Fusion deals usually contain a single large loan combined with a number of smaller loans. They are designed to provide a diversification benefit to offset the concentration risk represented by the large loan.

For example, defeasance, the more popular form of prepayment constraint in recent years, requires the borrower to deposit treasuries into the trust that mimic the terms of the underlying mortgage in order to prepay the loan.

Since the deal IDs from the two databases do not match, we have to manually build a crosswalk between the two databases based on deal issuance information. We lose quite a number of observations during the process of this match due to a combination of differences in coverage between CMAlert and Morningstar and difficulties in establishing matches between deals in both datasets. However, we find no statistical significant difference between the matched sample and the raw sample in many dimensions such as the size, the weighted LTV, subordination, loss rate, etc. So, we are not concerned with sample selection issues.

This predictive regression approach is used in other studies such as Plazzi et al. (2010).

The development of the senior/mezzanine/junior AAA CMBS structure may also reflect investors’ demands for CMBS bonds with a lower risk profile than those provided by the AAA subordination rate set by the CRAs.

Under our alternative scenario we assume state unemployment rates increase 3 percentage points, credit spreads rise 30 basis points while the term spread falls by the same amount, occupancy rates fall by 15 percentage points and the DSCR falls by 0.15 over the first three years of the loan.

A caveat of this aggregation is that we are ignoring default correlations that are due to unobservable common risk factors. However, since we’ve already included many of the common risk factors in the default hazard model, we don’t see the inclusion of such default correlations will change our results materially.

We are aware that some CMBS deals may have external credit enhancement but we do not believe that those external credit enhancements explain over 95 percent of the variations in ex ante credit risk.

References

An, X., & Vandell, K. D. (2013). Commercial Mortgages and Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities (CMBS). Forthcoming in H. Kent Baker and Peter Chinloy (eds.) Real Estate – Markets and Investment Opportunities. Oxford University Press.

An, X., Deng, Y., & Sanders, A. B. (2008). Subordination Levels in Structured Financing. In Arnoud Boot and Anjan Thakor (eds.) Handbook of Financial Intermediation and Banking, Elsevier. ISBN: 978-0-444-51558-2.

An, X., Deng, Y., Nichols, J. B., & Sanders, A. B. (2013). Local Traits and Securitized Commercial Mortgage Default. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 47(4), 787–813.

Bolton, P., Freixas, X., & Shapiro, J. (2012). The credit rating game. Journal of Finance, 67(1), 85–111.

Bongaerts, D., Martijn Cremers, K. J., & Goetzmann, W. N. (2012). Tiebreaker: certification and multiple credit ratings. Journal of Finance, 67(1), 113–152.

Cohen, A., & Manuszak, M. (2013). “Ratings competition in the CMBS market. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 45(1), 93–119.

DeMarzo, P. (2005). The pooling and tranching of securities: a model of informed intermediation. Review of Financial Studies, 18, 1–35.

DeMarzo, P., & Duffie, D. (1999). A liquidity-based model of security design. Econometrica, 67, 65–99.

Furfine, C. (2012). Complexity as a Means to Distract: Evidence from the Securitization of Commercial Mortgages. Northwestern University working paper.

Gaur, V., Seshadri S., & Subrahmanyam, M. G. (2005). Intermediation and Value Creation in an Incomplete Market. FMA European Conference 2005 working paper.

Geltner, D., & Miller, N. G. (2001). Commercial real estate analysis and investment. Mason: South-Western Publishing.

Ghent, A. C., Torous, W. N., & Valkanov, R. I. (2013). Complexity in Structured Finance: Financial Wizardry or Smoke and Mirrors? SSRN working paper.

Griffin, J. M., & Tang, D. Y. (2012). Did subjectivity play a role in CDO credit ratings? Journal of Finance, 67(4), 1293–1328.

He, J., Qian, J., & Strahan, P. E. (2012). Are all ratings created equal? The impact of issuer size on the pricing of mortgage-backed securities. Journal of Finance, 67(6), 2097–2138.

Keys, B., Mukherjee, T., Seru, A., & Vig, V. (2010). Did securitization lead to lax screening? Evidence from subprime loans. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(1), 307–362.

Plazzi, A., Torous, W., & Valkanov, R. (2010). Expected returns and the expected growth in rents of commercial real estate. Review of Financial Studies, 23(9), 3469–3519.

Riddiough, T. J. (1997). Optimal design and governance of asset-backed securities. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 6, 121–152.

Riddiough, T. J. (2004). Commercial mortgage-backed securities: An exploration into agency, innovation, information, and learning in financial markets. Madison: University of Wisconsin.

Riddiough, T. J., & Zhu, J. (2009). Shopping, Relationships, and Influence In the Market for Credit Ratings. SSRN working paper.

Sanders, A. B. (1999). Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities. In The Handbook of Fixed-Income Securities, edited by Frank J. Fabozzi. McGraw-Hill Co., 2000.

Sangiorgi, F., & Spatt, C. (2011). Opacity, Credit Rating Shopping, and Bias. SSRN working paper.

Seslen, T., & Wheaton, W. (2010). Contemporaneous loan stress and termination risk in the CMBS pool: how “ruthless” is default? Real Estate Economics, 38(2), 225–255.

Stanton, R., & Wallace, N. (2012). CMBS Subordination, Ratings Inflation, and Regulatory Capital Arbitrage. University of California, Berkeley working paper.

Titman, S., Tompaidis, S., & Tsyplakov, S. (2004). Market imperfections, investment flexibility, and default spreads. Journal of Finance, 59(1), 165–205.

Van Horne, J. C. (1985). Of financial innovations and excesses. Journal of Finance, 40(3), 621–631.

Vandell, K., Barnes, W., Hartzell, D., Kraft, D., & Wendt, W. (1993). Commercial mortgage defaults: proportional hazards estimations using individual loan histories. Journal of the American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association, 21(4), 451–480.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We are grateful to Peter DeMarzo, Michael Dewally, Mark Flannery, Sally Gordon, Dwight Jaffee, Tim Riddiough, Amit Seru, Walt Torous, Sean Wilkoff and participants at the 2007 RERI Research Conference, 2013 AREUEA Annual Meetings, the 2013 MFA Conference and the 2013 AREUEA International Conference for helpful comments. Special thanks are due to the Real Estate Research Institute (RERI) for its financial support. All remaining errors as well as the opinions expressed in this paper are our own responsibility. They do not represent the opinions of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System or its staff.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

An, X., Deng, Y., Nichols, J.B. et al. What is Subordination About? Credit Risk and Subordination Levels in Commercial Mortgage-backed Securities (CMBS). J Real Estate Finan Econ 51, 231–253 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-014-9480-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-014-9480-1