Abstract

We investigate whether a firm’s social capital and the trust that it engenders are viewed favorably by bondholders. Using firms’ environmental and social (E&S) performance to proxy for social capital, we find no relation between social capital and bond spreads over the period 2006–2019. However, during the 2008–2009 financial crisis, which represents a shock to trust and default risk, high-social-capital firms benefited from lower bond spreads. These effects are stronger for firms with higher expected agency costs of debt and firms whose E&S efforts are more salient. During the crisis, high-social-capital firms were also able to raise more debt, at lower spreads, and for longer maturities. We find no evidence that the governance element of ESG is related to bond spreads. The gap between E&S performance of firms in the bottom and top E&S terciles has narrowed since the financial crisis, especially in the year prior to accessing the bond market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Social capital, and the trust it engenders, can facilitate financial contracting by mitigating adverse selection and moral hazard problems. In this paper, we investigate the role of corporate social capital in a setting where managerial moral hazard is of particular concern: the corporate bond market. Given that the corporate bond market is the most important source of external capital for many large corporations (e.g., Philippon 2009), understanding the determinants of bond pricing and contracting terms is of key importance. Extant studies in this area show that credit spreads can be explained by default risk, liquidity, systematic risk, and market frictions.Footnote 1 We extend this literature by documenting the credit relevance of firms’ social capital and the resulting level of trust.

Trust, defined as “the expectation that another person will perform actions that are beneficial, or at least not detrimental, to us regardless of our capacity to monitor those actions” (Gambetta 1988), can be obtained in two ways. It can be “externally acquired” when a firm is located in a high-trust society or region (e.g., Guiso et al. 2004; Hasan et al. 2017a, 2017b), and/or it can be “internally generated” through a firm’s own investment in social capital. We refer to these two types of trust as Endowed trust and Earned trust, respectively. Studying the bond market effects of a firm’s earned trust is particularly interesting due to the discretionary nature of firms’ investments in social capital. We postulate that a firm’s internally generated social capital, and the trust it engenders, affect bond pricing and contracting through both a direct and an indirect channel.

The direct channel is via a reduction in the agency costs of debt. As a firm becomes financially distressed, managers, acting in the interest of shareholders, have incentives to expropriate bondholders by investing in risky projects even if these projects reduce firm value (Jensen and Meckling 1976). Similarly, managers of distressed firms have an incentive to pay out cash to shareholders in the form of dividends or repurchases prior to bankruptcy. Bondholders anticipate these potential agency costs and demand higher yields. These moral hazard concerns are alleviated, however, when trust is higher; if bondholders believe that managers care about the interests of a broad set of stakeholders, they will expect less risk shifting and/or cash diversion, as this can potentially jeopardize the firm’s survival. Thus, by mitigating the agency costs of debt, social capital can lower the firm’s cost of debt capital, particularly for those firms prone to asset substitution and cash diversion.

The indirect channel is a result of externalities. Firm-level evidence from the equity market suggests that a firm’s social capital helps build stakeholder cooperation, which delivers economic benefits in the form of higher cash flows and/or a reduction in risk (Edmans 2011; Servaes and Tamayo 2013; Guiso et al. 2015; Ferrell et al. 2016). Stakeholder cooperation should also be beneficial for bondholders, particularly when companies face financial difficulties. In such times, stakeholders of high-social-capital firms will likely exert additional effort to ensure the recovery of the firm. This is the reciprocity concept often discussed in studies of social capital (Fehr and Gächter 2000), which may lower the cost of debt for all firms investing in social capital, regardless of their potential for asset substitution and cash diversion.

We hypothesize that these channels are more relevant to bondholders when the overall level of trust in companies is low. In low-trust periods, bondholders are more likely to believe that companies will not protect creditor interests unless the firms themselves are deemed trustworthy. In such periods, firm-level trust earned via investments in social capital becomes more important, particularly for firms more able to increase asset risk or divert cash flows to shareholders. Of course, a competing view is that investments in social capital benefit some stakeholders but do not add value to the firm (e.g., Friedman 1970; Masulis and Reza 2015, 2021; Cheng et al. 2020). If the latter is true, bondholders will demand higher compensation to lend to high-social-capital firms.

To study whether high-social-capital firms reap financial benefits in the corporate bond market, we follow recent academic work in economics and finance (Aoki 2011; Sacconi and Degli Antoni 2011; Lins et al. 2017; Servaes and Tamayo 2017) and use a subset of a firm’s ESG (environmental, social, and governance) activities as a proxy for its investment in social capital. Our particular focus is on the environmental and social (E&S) elements of ESG because these factors correspond to the relation between the firm and its stakeholders, which is at the heart of the notion of social capital. The governance element of ESG, on the other hand, is generally concerned with the relation between the firm and its shareholders.Footnote 2 For a large sample of U.S. publicly traded firms, we investigate both secondary market bond trades and primary market bond originations between January 2006 and September 2019, covering both high- and low-trust periods.

We start by analyzing the relation between secondary market bond spreads and firms’ E&S performance over the full sample period. While endogeneity concerns make it difficult to draw causal inferences from such an estimation, our results indicate a modest negative E&S-credit spread relation, consistent with Goss and Roberts (2011), who study private debt. However, once we control for firm and time fixed effects, the modest relation between E&S performance and bond spreads disappears entirely.

Next, we turn to the financial crisis of 2007–2009. The crisis combines an exogeneous shock to firms’ default risk and an erosion of overall trust in firms, markets, and institutions, thereby increasing the potential importance of firm-level social capital for bondholders. Following prior work (e.g., Duchin et al. 2010; Ivashina and Scharfstein 2010; Sapienza and Zingales 2012; Lins et al. 2017), we identify two distinct periods: the credit-crunch period of July 2007–July 2008, when the supply of credit suffered a shock but general trust had not yet eroded; and the trust-crisis period of August 2008–March 2009, when a shock to trust occurred. The characterization of this period as one during which trust in business declined is also consistent with survey evidence. Edelman, the world’s largest independent public relations firm, reports that trust in business in the U.S. remained stable until early 2008 (53% in early 2007 and 58% in early 2008) but declined precipitously, to 38%, in early 2009. It is important to note that the erosion of trust was not solely confined to the financial sector; each of the twelve broad industries covered by the Edelman Trust Barometer experienced a decline in trust in early 2009 relative to the previous year. This allows us to compare the bond market effects of social capital when overall trust was severely eroded, relative to a period when credit market access was constrained.

We conduct difference-in-differences tests using the shock to trust as a quasi-experimental setting. For identification, we use pre-crisis levels of E&S performance, as it is unlikely that firms adjusted their E&S activities in anticipation of the financial crisis. Because the crisis is a plausibly exogenous event with respect to firms’ pre-crisis E&S decisions, our empirical strategy circumvents endogeneity concerns that arise in studies of the capital market effects of E&S performance.

Our results are unambiguous: during the crisis of trust, the secondary market bond spreads of high-E&S firms did not rise as much as the spreads of low-E&S firms. Further, we find that the documented effect is stronger for firms that have more incentives or opportunities to engage in asset substitution (e.g., Williamson 1988; Johnson 2003) or to divert cash to shareholders when in distress (e.g., Wald and Long 2007), such as firms with a high probability of default, firms with fewer tangible assets, and firms incorporated in states that do not impose payout restrictions on insolvent firms. For these firms, the implicit commitment that such activities are unlikely to occur, as captured by E&S investments, is most valuable. We also find larger effects for firms whose E&S efforts are more salient, as evidenced by the publication of a separate ESG (CSR or sustainability) report or the inclusion of an ESG (CSR or sustainability) section in their annual report.

To further establish the credit relevance of social capital in low-trust periods, we also examine the secondary bond market response to events that eroded trust in specific industries (as opposed to eroding trust in corporations in general). Specifically, we study the change in bond spreads of oil and gas firms around the 2010 BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill and of financial firms around the 2016 Wells Fargo cross-selling scandal. In both cases, we find that the spreads were lower for high-E&S firms.

Next, we focus on the primary bond market and show that during the crisis of trust, high-E&S firms were able to raise more debt, at lower at-issue spreads, and for longer maturities. These results further confirm the positive role of social capital in the corporate bond market.

Given the documented benefits of E&S during low-trust periods, we conclude our empirical analyses by examining the time-series pattern of firms’ E&S performance since the financial crisis. Consistent with the notion of firms learning about those benefits over time, we document an overall increase in E&S performance in subsequent years. Interestingly, firms with lower E&S performance prior to the crisis make the largest adjustments, particularly in the year immediately before they access the primary bond market.

Overall, our results show that corporate social capital affects bond pricing and contracting when it matters most: during a crisis of trust, when bondholders seek reassurance that they will not be expropriated. In such periods, a firm’s social capital is perceived as a quasi insurance policy against excessive risk taking that can harm bondholders and other stakeholders.Footnote 3

Our findings contribute to three strands of the literature. First, we extend nascent studies on the role of social capital in financial contracting by highlighting its importance for the corporate bond market, particularly for firms with higher agency costs of debt and in crisis-of-trust periods. Prior work (e.g., Hasan et al. 2017b) shows that U.S. firms domiciled in high-trust regions, i.e., those with higher Endowed trust, incur lower at-issue spreads for both bank loans and bonds.Footnote 4 In contrast, we focus on the type of trust that firms can more easily influence via their discretionary investments in social capital – Earned trust – and show that it affects bond spreads, mainly when overall trust in companies is low. Our findings also complement those of Lins et al. (2017) by showing that the E&S benefits they document for the equity market carry over to the bond market.Footnote 5 Whether or not this should be the case is ex ante unclear, as the superior stock returns of high-E&S firms could, in principle, come at the expense of bondholders due to increased asset substitution or diversion. Our evidence showing that the E&S-credit spread relation is stronger when bondholders are more exposed to debt agency costs rejects the asset substitution/diversion explanation. In addition, the principal mechanism explaining our results, the reduction in debt agency costs, is different from the main channel explaining the results in Lins et al. (2017), which is reciprocity. As such, our findings add to our understanding of the importance of perceived agency costs in the pricing of corporate debt. Considered collectively, the bond market benefits we document in this study, together with the favorable equity market effects reported in Lins et al. (2017), suggest that, at least in some circumstances, greater trust can increase the overall enterprise value of a firm (and not just the value of its equity).

Second, we provide new evidence on the determinants of corporate bond spreads by documenting the credit relevance of firms’ social capital, as proxied by environmental and social metrics. Importantly, since firms have discretion over their E&S investments, our evidence points to an additional channel through which firms may influence their cost of debt.

Third, our results add to the literature on the determinants of firms’ contractual arrangements with creditors in the primary bond market (e.g., Berger and Udell 1998; Billett et al. 2007; Chava et al. 2010). Our evidence on high-E&S firms’ ability to attract more debt capital at more favorable terms during the financial crisis suggests that internally generated social capital can contribute to establishing trust and mitigating agency frictions between contracting parties.

2 Sample and summary statistics

2.1 Sample construction

To construct our sample of corporate bonds on the secondary market, we start with the universe of bonds covered in the Enhanced Historic TRACE database from January 2006 to September 2019. Following Dick-Nielsen et al. (2012), we exclude variable- and zero-coupon, perpetual, foreign currency, preferred, puttable, and exchangeable issues as well as private placements and Yankee and Canadian bonds. We further restrict our selection to corporate debentures and corporate medium-term notes with a time-to-maturity of more than one month and 30 years or less. To be included in our sample, we require that data on fundamental bond contract attributes (i.e., issue size, offering and maturity dates, and coupon rates) are available on the Mergent Fixed Income Securities Database (FISD). To address liquidity biases and erroneous entries in TRACE, we follow the method in Dick-Nielsen (2014).Footnote 6 We further apply the quantity, price, and yield filters used in Becker and Ivashina (2015) and Han and Zhou (2016) to remove outliers and observations with likely data errors.Footnote 7

We merge this sample with E&S ratings data from the Thomson Reuters Refinitiv ESG database, which contains annual environmental, social, and governance ratings of large publicly listed companies, covering over 80% of global market capitalization, across more than 450 different ESG metrics. The data are compiled using information from corporate annual reports, sustainability reports, nongovernmental organizations, company websites, stock exchange filings, and news sources for publicly traded companies at an annual frequency. This database has been used in a number of recent studies examining the causes and consequences of firms’ environmental and social performance (e.g., Dyck et al. 2019; Albuquerque et al. 2020). Its U.S. coverage comprises roughly the largest 3,000 companies.

A potential shortcoming of the Refinitiv ESG database is that some of the historical data may be revised over time to reflect new information, which could affect certain inferences (see Berg et al. 2021). As a sensitivity test, we re-estimate our main specifications using E&S metrics constructed from the MSCI ESG KLD STATS database for our sample of firms. Our main findings hold using this metric as well.Footnote 8,Footnote 9

We obtain annual fundamentals from Compustat, daily stock returns from the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP), bond duration from the Wharton Research Data Services (WRDS) bond returns database, bond ratings from Mergent FISD, and probability of default data from the Credit Research Initiative of the Risk Management Institute at the National University of Singapore.

Merging these databases yields a final sample of 5,631 corporate bonds, issued by 808 firms, with secondary market trade data from January 2006 to September 2019, as noted in Panel A of Table 1. Panel B outlines the distribution of the sample across the Fama–French 12 industries. The finance industry constitutes the largest proportion of bond issues (23.1%), while the other sectors have a fairly balanced representation in the overall sample (except consumer durables, which represents only 1.5% of all bonds).

2.2 E&S index variable construction and descriptive statistics

Our main independent variable is the E&S index, which we construct using environmental (E) and social (S) performance data from the Thomson Reuters Refinitiv ESG database. Refinitiv ESG evaluates firms’ environmental performance in three categories: resource use, emissions, and innovation. Social performance is measured in four areas: workforce, human rights, community, and product responsibility. For both E and S performance, Refinitiv provides, for each firm in each year, a score that ranges from 0 to 100, which we use to form our E&S index.Footnote 10 Following Albuquerque et al. (2020), we define the E&S index as the average of the Refinitiv E score and the S score. We do not include the governance metric in our E&S index because governance speaks most directly to the relation between the firm and its shareholders, while investments in social capital reflect the relation between the firm and its stakeholders, as captured by E&S performance. However, since prior studies have shown strong governance to be beneficial to bondholders (e.g., Bhojraj and Sengupta 2003; Klock et al. 2005; Bradley and Chen 2011, 2015), we also control for governance in our estimations.

Our main dependent variable is a bond’s credit spread, computed as the difference between the bond’s yield to maturity from the Enhanced Historic TRACE database and the Treasury yield matched by maturity (e.g., Campbell and Taksler 2003; Chen et al. 2007; Huang and Huang 2012).Footnote 11 As in Becker and Ivashina (2015), we employ the median yield of all transactions taking place on the last active trading day of a given month to compute the bond spreads.

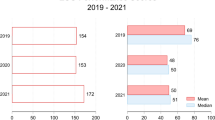

Table 2 provides summary statistics on the characteristics of the bonds in our sample, the E&S index, environmental and social scores, credit spreads, and other control variables. The Appendix contains detailed definitions of all the variables employed in our analyses. Panel A reports the fundamental bond contract features that remain constant over the life of bond. As such, we count each bond issue only once in the summary statistics. The mean issue size in our sample is $711 million with an average annual interest rate just below 4.7%.

Panel B of Table 2 contains the bond characteristics that could vary on a monthly basis. As such, we count each bond-month pair as a separate observation. The bonds in our sample have a mean time-to-maturity of just over 9.8 years (118 months). Credit ratings are converted to numerical values, starting with 1 for AAA ratings through 21 for C ratings. The mean credit rating of 8.2 indicates that the bonds in our sample are rated between BBB and BBB + , on average.Footnote 12 There is considerable variation in credit spreads, with an average of just under 179 basis points and a standard deviation of 545 basis points. We do not winsorize the spreads because they are larger during the financial crisis and winsorization would disproportionally affect these observations. However, all of our findings persist if we winsorize spreads at the 99th percentile, albeit with reduced, but still considerable, economic significance.

Panel C of Table 2 reports summary statistics on firm characteristics. All of them vary annually, except for stock return volatility and probability of default, which are computed monthly. The firms in our sample are large (average market capitalization of $25.4 billion) and profitable (operating income to sales of 20.8%).

3 The E&S-credit spread relation

In this section, we examine the relation between E&S performance and bond spreads over the entire sample period from January 2006 to September 2019. We conduct this analysis by regressing credit spreads in the secondary bond market on firm E&S ratings and controls. As a firm’s E&S activities are likely jointly determined with other firm characteristics, we are not able to draw any causal inferences from this analysis. Our results should therefore be viewed as suggestive of correlations only.

Specifically, we estimate the following pooled regression model using monthly spread data:

where Credit spreadijt denotes the spread of firm i’s bond j in month t, and E&S indexit-1, our explanatory variable of interest, is firm i’s measure of environmental and social performance computed at time t-1. Xijt-1 is a (K×1) vector of bond-level controls measured at time t-1, and Zit-1 is a (L×1) vector of firm-level controls measured at time t-1. In addition, we include firm fixed effects, FFEi, to control for unobservable time-invariant credit risk factors. Note that any regional social capital effects of the type analyzed by Hasan et al. (2017b) will be subsumed by the firm fixed effects. We double cluster the standard errors at the firm and time (monthly) levels to control for cross-sectional and time-series dependence, respectively (Petersen 2009).Footnote 13

Consistent with Correia et al. (2012) and Correia et al. (2018), we include the following control variables: Duration, Probability of default, Credit rating, Offering amount, Time-to-maturity, and Coupon. For our sample, we use modified duration obtained from the Wharton Research Data Services (WRDS) bond returns database and probability of default (over 12-month windows) from the Credit Research Initiative of the Risk Management Institute at the National University of Singapore.Footnote 14 Their probability of default methodology follows Duan et al. (2012) and is constructed using a forward intensity function, whose inputs include the state of the economy (macro-financial risk factors) and the vulnerability of individual obligors (firm-specific attributes). There is a significant negative correlation between our E&S measure and the probability of default (ρ = −0.072), suggesting that inclusion of this control is particularly important. We further control for contemporaneous bond liquidity using the Amihud (2002) illiquidity measure, which captures the price impact of trades. Because this measure requires multiple trades in a given day, it is not available for all bonds in our sample. All other bond-level controls are obtained from Mergent FISD and Enhanced TRACE.

Our issuer-level controls also follow prior research on corporate bonds (e.g., Campbell and Taksler 2003; Chen et al. 2007; Acharya et al. 2012) and include Market equity, Profitability, Inverse leverage, Coverage ratio, and Stock return volatility. Finally, we control for corporate governance, as past studies suggest that debt investors demand lower spreads for bonds of better-governed firms (e.g., Klock et al. 2005; Bradley and Chen 2015). We use the Governance (G) pillar score from the Refinitiv ESG database as a proxy for corporate governance quality. The accounting-based firm characteristics and ESG data are updated annually in accordance with firms’ corporate reporting patterns. To ensure that the accounting and ESG data are publicly available, we update these items three months after a firm’s fiscal year-end. Volatility is re-estimated each month based on the previous year’s daily returns data.

Our findings from estimating Eq. (1) are reported in Table 3. We first present the results from a simple regression of credit spreads on the E&S index, controlling for firm fixed effects (model (1)). The coefficient on E&S is −0.010 and highly significant, suggesting that high-E&S firms have lower credit spreads. Next, we control for the main bond-level attributes (model (2)) and find that the coefficient on E&S is less pronounced at −0.005, but remains significant at the 10% level. The modest negative relation between E&S and credit spreads that we document in the first two models of Table 3 is consistent with prior work on bank loans (e.g., Goss and Roberts 2011; Hasan et al. 2017b).

In model (3), we include time fixed effects (monthly dummies). The coefficient on the E&S index becomes statistically (and economically) insignificant in this specification. This result indicates that, on average, there is no relation between firms’ E&S performance and bond credit spreads and highlights the importance of controlling for the overall time-series variation in spreads, in addition to firm fixed effects, when estimating models of bond yields. In model (4), we further control for firm-level characteristics that may vary over time, and in model (5) we also control for the quality of governance; the inclusion of these controls has no additional impact on our results.

We conduct five additional tests, the results of which are untabulated for the sake of brevity. First, we estimate the models without firm fixed effects. In such models, we do find a significant negative relation between credit spreads and the E&S index, which suggests that failure to control for unobservable time-invariant firm-specific heterogeneity has a substantial impact on the inferences that can be drawn from this analysis. Second, we examine the relation between credit spreads and the individual social and environmental scores included in our E&S measure. Consistent with the results reported in Table 3, the relation between these two scores and credit spreads becomes insignificant once firm and time fixed effects are included. Third, we confirm that the absence of a relation between bond spreads and E&S performance holds for both nonfinancial and financial firms. Fourth, we find that excluding sample firms that participated in the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) during the financial crisis does not affect our inferences. Finally, we investigate whether the E&S-credit spread relation is stronger for firms with a higher probability of default, firms with more intangible assets, or firms incorporated in states that provide less bondholder protection during insolvency. All of these firms have more of an incentive or opportunity to shift risk and divert cash to shareholders at the expense of bondholders. We do not find that any of these factors affect the E&S-credit spread relation.Footnote 15

4 E&S performance and credit spreads: evidence from an exogenous shock to trust

4.1 E&S performance and credit spreads during the financial crisis

In this section, we seek to understand whether the bond market payoffs to firms’ E&S activities are more pronounced when overall trust is low and a firm’s social capital may become more valuable. To do so, we focus on the financial crisis, which constituted an exogenous shock to public trust in corporations, capital markets, and institutions and led to a decline in stock prices and an increase in bond spreads for the vast majority of firms.

The exogenous nature of the financial crisis helps alleviate the endogeneity concerns associated with Eq. (1). The underlying assumption is that the crisis is exogenous with respect to firms’ decisions to engage in E&S activities. In particular, firms decide on the optimal level of E&S investments during normal times, when the probability of a crisis and a decline in overall trust is relatively low. During normal times, some firms do not engage much in E&S activities because they do not view them as worth the cost, while others invest in E&S activities because they expect them to be beneficial. When the crisis hits, the value of social capital that firms have built through E&S investments becomes apparent. For firms that invested little in E&S during the pre-crisis period, however, it is too late to make such investments, as corporate social capital takes time to build.Footnote 16

Our sample period for this analysis begins in January 2007, prior to the onset of the crisis, and ends in September 2019. We adopt a quasi-difference-in-differences approach and examine whether firms that entered the crisis period with higher E&S ratings enjoyed relatively lower spreads during the crisis.Footnote 17 Specifically, we estimate the following model:

where, as before, Credit spreadijt denotes the spread of firm i’s bond j in month t, Xijt-1 is a (K×1) vector of bond-level controls measured at time t-1, and Zit-1 is a (L×1) vector of firm-level controls measured at time t-1. We include firm fixed effects, FFEi, to control for unobservable time-invariant credit risk factors, and time fixed effects, TFEt, specified at the monthly level.Footnote 18 We measure the E&S index as of year-end 2006, well before the onset of the financial crisis, to eliminate the concern that firms might have adjusted their E&S activities in anticipation of the crisis.Footnote 19Crisist is an indicator variable that takes the value of 1 for the crisis-of-trust period, which starts in August 2008 and ends in March 2009 (as in Sapienza and Zingales 2012 and Lins et al. 2017), and Post-crisist is an indicator variable that takes a value of 1 from April 2009 to September 2019. As before, we double cluster the standard errors at the firm and time (monthly) levels to control for cross-sectional and time-series dependence, respectively. Inclusion of firm fixed effects and firm and bond characteristics ensures that the crisis-E&S effect is not due to healthier firms spending more on E&S activities and performing better during the crisis.

In Eq. (2), the coefficient on the interaction term E&S indexi2006×Crisist, β1, captures the difference between the effect of E&S performance on credit spreads in the crisis versus the pre-crisis periods (the pre-crisis effect itself is captured by the time and firm fixed effects). The coefficient on the interaction term E&S indexi2006×Post-crisist, β2, captures the difference between the effect of E&S performance on credit spreads in the post-crisis versus the pre-crisis periods. This coefficient could also be negative given that overall trust in corporations, markets, and institutions continued to be low after the crisis for some time. However, in absolute terms, we expect β1 to be larger than β2, because the most pronounced erosion of trust occurred during the crisis.

The results from estimating Eq. (2) are reported in Panel A of Table 4. In model (1), we include only firm and time fixed effects and the E&S index interactions. We then control for bond attributes in model (2) and add firm characteristics in model (3). All three models indicate that E&S performance has a statistically and economically significant impact on bond spreads during the crisis. Based on the regressions reported in model (3), a one standard deviation increase in the pre-crisis E&S index is associated with 106 basis points lower spreads during the crisis period.Footnote 20 The benefit that accrued to high-E&S firms during the crisis disappears in the post-crisis period (the difference between β1 and β2 is statistically significant at the 1% level in all three specifications).

In model (4), we also control for corporate governance using the governance pillar score from the Refinitiv ESG database. Prior evidence suggests that better-governed firms have lower bond spreads. These firms also performed better during the crisis (Lins et al. 2013; Nguyen et al. 2015); thus, if governance is correlated with our measure of E&S performance, we could be suffering from an omitted variable bias. The coefficient on the E&S index remains virtually unchanged in this specification; hence, the impact of E&S performance on bond spreads during the crisis cannot be attributed to better governance, as captured by the G pillar score. The governance score itself is not significantly related to bond spreads.Footnote 21

Figure 1 presents our findings graphically. To construct this figure, we partition our sample firms into two groups based on their E&S index at the end of 2006. We then estimate a panel regression of credit spreads as a function of all control variables (including the governance pillar score) as well as separate monthly time dummies for high- and low-E&S firms. The coefficients on these time dummies are akin to monthly intercepts for high- and low-E&S firms. The figure presents the plot of these monthly dummies over time. The variation in the differential between characteristic-adjusted spreads of high- and low-E&S firms over time is striking. For most of the sample period, there are only small differences between the two groups. However, after August 2008, the difference between the two groups shoots up, reaching its maximum level in November 2008. The differential remains high until March 2009, when the stock market hit its lowest point of the crisis; afterwards, the difference declines and the two lines often cross and overlap. The period of August 2008–March 2009 (the shaded area in the figure), when the difference becomes considerable, coincides with the crisis of trust as defined in our regression models.Footnote 22

Characteristic-adjusted secondary market credit spreads (2007–2019) for high- and low-E&S firms. To construct this figure, we partition our sample firms into two groups based on their E&S index at the end of 2006. We then estimate a panel regression of credit spreads as a function of all the control variables (including the governance pillar score) as well as separate monthly time dummies for high- and low-E&S firms. The figure presents the plot of these monthly dummies over time. The period of August 2008–March 2009 (shaded area) coincides with the crisis of trust described in Sapienza and Zingales (2012) and Lins et al. (2017)

Next, we investigate whether these findings persist for various subsamples and when we divide the E&S index into its environmental and social components. Panels B–D of Table 4 present the regression models separately for nonfinancial firms, financial firms, and financial firms that did not receive TARP funding. For the sake of brevity, we report only the main E&S effects in the tables. We find significant effects for all sets of firms. However, the effect is significantly larger for financial firms, which is not surprising, given that their credit spreads increased much more during the crisis than the credit spreads of nonfinancial firms. After removing financial firms that received TARP funding, the effect becomes even larger.Footnote 23 Note that for the latter subsample, we also find a significant effect in the post-crisis period. Given that trust in banks was not fully restored after the financial crisis, a continued negative relation between spreads and E&S performance is consistent with our conjecture.Footnote 24 In terms of economic significance, increasing the pre-crisis E&S index for financial firms by one standard deviation (18.0) led to lower spreads of 167 basis points during the crisis and 65 basis points in the post-crisis period (based on model (3) of Panel C of Table 4).Footnote 25

In Panel E of Table 4, we partition the E&S index into its environmental and social components. Each component is significantly related to credit spreads in the specifications that include both firm and bond controls (models (3) and (4)), suggesting that social capital stems from both environmental and social elements. Increasing the environmental component by one standard deviation (25.9) reduces spreads by 49 basis points during the crisis, while increasing the social component reduces spreads by 69 basis points (based on model (4)).

From these analyses, we conclude that the bond spreads of high-E&S firms increased less during the financial crisis than the spreads of low-E&S firms. For financial firms, this effect persisted in the post-crisis period. These findings are consistent with bondholders valuing a firm’s social capital and its “earned trust” more in periods when being trustworthy is particularly important, such as in a crisis of trust.

4.2 E&S performance and credit spreads during the credit crunch

Next, we conduct further analyses to corroborate that our results are indeed driven by a shock to market-wide trust rather than a shock to the supply of credit. In July 2007, LIBOR rates started to increase dramatically as the solvency of the banking sector weakened, which had a negative impact on the ability of firms to borrow (e.g., Duchin et al. 2010; Ivashina and Scharfstein 2010). This shock to the supply of credit persisted until at least March 2009, and thus partly overlaps with the period during which there was a shock to trust. If high-E&S firms were less affected by the credit crunch, the differential in the spreads that we document could be due to this phenomenon rather than a shock to trust. High-E&S firms may have been more able to borrow over the credit crunch, given that the agency costs of debt argument that we describe could hold in any crisis. Our contention, however, is that if a firm’s E&S investments engender trust, the effect of E&S performance on credit spreads should be particularly salient when trust is more valued.

As discussed, Fig. 1 suggests that the difference in spreads between high- and low-E&S firms becomes noticeable starting in August 2008 and not earlier. However, to investigate bond spreads during the credit crunch more formally, we augment Eq. (2) with an interaction term between the E&S index and the “pure” credit-crunch period, which we define as the period of July 2007–July 2008. During this period, the shock to credit supply had already happened, but the shock to trust had not yet occurred (Sapienza and Zingales 2012; Lins et al. 2017). As in Panels A–E of Table 4, we estimate various specifications of this augmented regression, starting with a more parsimonious model and sequentially adding controls in subsequent specifications. The findings are reported in Panel F of Table 4. Across all models, we find that the impact of the E&S index on credit spreads is much more pronounced during the crisis than in the surrounding periods. There is some evidence of a negative relation during the credit crunch and the post-crisis periods, but with a much lower economic significance. Moreover, the effect of the E&S index on credit spreads is significantly different between the crisis and the credit crunch and between the crisis and the post-crisis periods across all specifications. Overall, the results reported in Panel F of Table 4 indicate that the effect of E&S performance on bond spreads is most pronounced during the loss-of-trust period relative to the surrounding periods.

4.3 Mechanisms

To better understand the mechanisms behind our findings, we conduct six additional tests. First, we split the sample into two groups based on the probability of default at the end of 2006 and estimate separate models for each subsample. Firms with a higher probability of default have more of an incentive to engage in asset substitution to expropriate their bondholders, since they are closer to bankruptcy. If E&S activities reduce the agency costs of debt, we expect the influence of E&S performance on spreads to be particularly germane for this group of firms. The estimated models include all control variables (including the governance pillar score), equivalent to model (4) of Table 4. The results are reported in models (1) and (2) of Panel A of Table 5. While the effect of the E&S index on bond spreads is significant for both groups of firms, it is much larger for firms with a higher probability of default, and the difference between the two is statistically and economically significant; increasing the E&S index by one standard deviation reduces bond spreads of firms with a high default probability by 99 basis points, compared to 21 basis points for firms with a low probability of default. This result supports the notion that our findings are due to the perception of reduced agency costs of debt in high-E&S firms. We also note that there is some evidence of narrower spreads in the post-crisis period for high-E&S firms with a higher probability of default. This finding is consistent with the fact that, in the post-crisis period, trust had not been fully restored (for example, the trust component of the Global Competitiveness Index of the World Economic Forum was still lower in September 2016 than in September 2007). Thus, social capital remains relevant after the crisis for firms that are more likely to engage in asset substitution.Footnote 26

Second, we investigate whether the effect of E&S performance on spreads during the crisis is more pronounced in firms with low asset tangibility. Williamson (1988) and Johnson (2003) argue that these firms have more of an opportunity to engage in asset substitution when distress risk increases. If the spreads of high-E&S firms are lower during the crisis than those of low-E&S firms because bond investors expect less asset substitution from high-E&S firms, then this effect should be more pronounced for firms that have more opportunities to shift risk. We investigate this possibility by splitting the sample into two groups according to asset tangibility, defined as property, plant, and equipment (net) divided by total assets. Firms are assigned to a group based on tangibility as of year-end 2006, and this grouping remains unchanged throughout the full sample period. In model (3) of Panel A of Table 5, we report the results of the spreads regression for firms with tangibility below the median (< 18.24%). For this group, the E&S index has a strong negative impact on spreads during the crisis period, but not afterwards. In model (4), we report the results for the high tangibility group. The coefficient on the E&S index×Crisis interaction for this subsample is less than half the coefficient of the low tangibility sample, and the difference between the two coefficients is statistically significant. The fact that our results are much stronger for the subgroup of firms that have more opportunities to engage in asset substitution supports our contention that bond investors believe that high-E&S firms are less likely to take advantage of that opportunity.

Third, we examine whether our results are stronger for firms incorporated in states that provide weaker bondholder protection in case of insolvency. In particular, we use the classification of Wald and Long (2007) and Mansi et al. (2009) to divide states into two groups, depending on whether or not they allow firms with negative book equity to make payouts. Mansi et al. (2009) find that bond yields are higher in states without payout restrictions, which indicates that bondholders penalize firms for the possibility that cash flows will be diverted to shareholders in case of financial distress. The results for this analysis are reported in models (5) and (6) of Panel A of Table 5. The effect of the E&S index on credit spreads during the crisis is significant in both groups, but larger in states where firms face no restrictions on payouts during insolvency. The difference between the two is not statistically significant at conventional levels, however. We also find some evidence that the effect of the E&S index on spreads persists in the post-crisis period for firms incorporated in states without payout restrictions, consistent with the view that social capital has remained important for the firms most prone to asset diversion.

In models (7) and (8) of Table 5, we combine both the tangibility and payout criteria. In model (7), we focus on firms with either low tangibility or no state-level payout restrictions, or both. These firms have higher agency costs of debt, and social capital, for them, is likely more important during the financial crisis. This is exactly what we find. Model (8) includes firms with high tangibility that also face state-level payout restrictions. For these firms, agency costs of debt are lower and social capital is likely to have a smaller influence on bond spreads. The results support this notion, as the coefficient on the E&S index×Crisis interaction is half that of model (7).

Fourth, we study whether our findings are affected by the salience of E&S investments. We focus on two elements that reflect the importance that companies attribute to E&S activities. First, does the company publicly disclose its E&S activities either in the form of a standalone ESG (CSR or sustainability) report or a separate section in its annual report?Footnote 27 If bond investors find these disclosures to be material, we would expect our findings to be more pronounced for firms that report on their E&S activities.Footnote 28 Second, does the company have an ESG committee or team? Having such a team would suggest that E&S activities are not peripheral to the company’s strategy and business model. To compile data on these two elements, we employ the Refinitiv ESG database, augmented by two databases: (a) The Corporate Register, the world’s most comprehensive database of ESG reports, and (b) The Corporate Sustainability Assessment database provided by RobecoSAM, an international asset management company focused on evaluating corporate sustainability practices. We obtain this information for year-end 2006 and keep it constant throughout the sample period. In Panel B of Table 5, we report results for sample splits based on these two data items. In the first two columns, we report results for splits based on ESG reporting, and in models (3) and (4) we report splits based on having an ESG committee. The partition based on the availability of an ESG report supports the notion that E&S performance has a significantly stronger effect on bond spreads during the crisis for firms whose E&S activities are more salient. The presence of an ESG committee, on the other hand, has no effect on the E&S index-credit spread relation. In models (5) and (6), we compare firms that have at least one of these two elements to firms that lack E&S salience altogether. We continue to find that the E&S index has a stronger effect on spreads during the crisis for firms with more salient E&S activities. These findings suggest that bond spreads are not only influenced by the underlying E&S performance but also by the salience of those activities.

Fifth, since Lins et al. (2017) find that high-E&S firms earned excess stock returns during the crisis compared to low-E&S firms, we seek to determine whether the bond spread effect that we document is incremental to the stock return effect or whether the bond market performance is merely a reflection of superior stock market performance. To discriminate between these two possibilities, we conduct two tests. In the first test, we control for the firm’s contemporaneous stock returns in the spreads regression of model (2). Moreover, we allow the effect of returns to vary during the crisis- and post-crisis periods. Specifically, we estimate the following augmented regression model:

where Rit is firm i’s raw stock return during month t and all other explanatory variables follow earlier definitions. The findings from estimating this regression are reported in Table 6. In model (1), the effect of contemporaneous stock returns is held fixed throughout the period, while in model (2) we allow the stock return effect to vary across subperiods. Both models illustrate that the effect of E&S activities on bond spreads during the crisis is incremental to the stock price effect and therefore cannot be inferred from the prior evidence on stock returns. Moreover, the coefficient on the E&S index is similar to that in the models that do not control for stock returns.

In the second test, we investigate whether the cross-sectional patterns documented for bond spreads in Panel A of Table 5 can be inferred from the stock market findings of Lins et al. (2017). To do so, we replicate their stock market results for our sample, splitting the data according to probability of default, tangibility, and the ability to make payouts when distressed (our agency cost of debt proxies). If the reduction in credit spreads for high-E&S firms during the crisis is driven by the same factors that explain stock returns, then we should observe similar cross-sectional patterns in stock returns (i.e., high-E&S firms should have higher stock returns during the crisis when they have a higher probability of default, lower tangibility, and are more able to make payouts when in distress). In untabulated tests, we do not find this to be the case: there is no consistent pattern in stock returns across these three proxies.

Sixth, instead of controlling for stock returns in the bond regressions, we control for operating performance using the four measures employed by Lins et al. (2017): operating profitability, gross margin, sales growth, and sales per employee. While we find that credit spreads are lower for firms with better operating profitability, the effect of the E&S index on bond spreads during the crisis persists with similar economic and statistical significance (not reported in a table).

Overall, the findings from these additional tests indicate that the effect of E&S performance on bond spreads during the crisis reflects bondholders’ expectations of the likelihood of asset substitution or diversion taking place. As such, the key bond market benefit of E&S investments during the financial crisis is a reduction in the perceived agency costs of debt. This effect appears to be particularly pronounced in firms whose E&S activities are more salient.

5 Loss of trust at the industry level

Our findings thus far support the view that when trust in corporations, markets, and institutions declined during the financial crisis, the social capital that firms built through their E&S investments led to relatively lower credit spreads for these companies. In this section, we explore whether our conjecture about the bond market benefits of social capital during a crisis of trust also applies in more localized settings where trust declines only for a certain sector of the economy.

The first event we consider is the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill, caused by an explosion on the firm’s drilling rig in the Gulf of Mexico on April 20, 2010. This event led to a temporary loss of trust in all oil and gas companies and the energy sector as a whole. The Edelman Trust Barometer for the energy sector showed a decline in trust from 50% in early 2010 to 43% in early 2011, recovering to 54% in early 2012.Footnote 29 To study the consequences of this event, we employ all firms in our sample in the oil and gas sector from January 2010 to September 2019 (n = 39). We fix the E&S index as of year-end 2009 and define the loss-of-trust period as being from April 2010 to December 2011. We then estimate our baseline regression models for firms in this industry. The results are reported in Panel A of Table 7. For the sake of brevity, we only report the coefficient on the interaction term between the loss-of-trust period and the E&S index. We find that the E&S index is negatively related to spreads when trust declined. In terms of economic significance, increasing the E&S index by one standard deviation (25.2 for this subsample) led to relatively lower credit spreads of 30 basis points during this loss-of-trust period (based on model (3)).

The second event we study is the Wells Fargo cross-selling scandal, brought about by the creation of millions of fraudulent savings and checking accounts on behalf of the bank’s clients without their consent. As a result of this scandal, Wells Fargo agreed to pay $185 million in fines to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and the City and County of Los Angeles in September of 2016. Allegations about fraud surfaced as early as 2013 and became more prominent in January of 2016. As a result, trust in banking, which had started to recover after the 2008–2009 financial crisis, suffered another breakdown, from which it had not fully recovered by September 2019. To study the impact of this event on the E&S index-credit spread relation, we use our sample data for all financial firms from January 2014 to September 2019 (n = 115). Wells Fargo itself is removed from the sample because we do not want to capture the direct effect of the scandal and the fines. We fix the E&S index as of year-end 2013 and define the loss-of-trust period as January 2016–September 2019. We estimate our baseline models for this event and report the results in Panel B of Table 7. The findings suggest that during the loss-of-trust period there was a negative relation between spreads and E&S performance of financial institutions. Increasing the E&S index by one standard deviation (23.8 for this subsample) led to a relative decline in credit spreads of 17 basis points over this period (based on model (3)).

To conclude our discussion on localized settings, we describe the (untabulated) results from two additional industry-specific shocks to trust, each of which affected only a few sample firms with publicly traded bonds. The first event occurred on April 24, 2013, when the Rana Plaza building collapsed in Dhaka, Bangladesh, killing more than 1,100 workers. The building housed five garment factories employed by American, European, and Asian apparel manufacturers and retailers, and its collapse led to a loss of trust in these companies. We employ data on U.S. companies in this sector that have publicly traded bonds outstanding (n = 7) over the January 2012–September 2019 period. We fix the E&S index at the end of 2011 and define the loss-of-trust period as starting in April 2013 and continuing until December 2014. We find that during this period, high-E&S firms had significantly lower credit spreads. The second event is a crisis of trust that occurred in the pharmaceutical industry. Since the start of 2016, the industry has been plagued by claims of price gouging, and in 2017 the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency. These events had a profound effect on the overall level of trust in the industry. According to Gallup, Americans’ views of the pharmaceutical industry dropped from 4% net positive (positive view minus negative view) in 2015 to −23% in 2016 and −31% in 2019. In support of our conjecture that E&S activities have a negative effect on credit spreads when trust is lower, we find a negative relation between the E&S index and bond spreads for pharmaceutical firms starting in 2016.

In sum, the evidence reported in this section indicates that E&S performance negatively affects credit spreads during low-trust periods in specific industry sectors.

6 E&S performance, bond originations, and contracting terms

Our results thus far show that high-E&S firms benefited from relatively lower spreads on their outstanding bonds during the crisis of trust that occurred in 2008–2009 and during a number of industry-specific loss-of-trust events. In this section, we examine whether these benefits carry over to the primary bond market. Specifically, we investigate whether, during the global financial crisis, high-E&S firms were able to raise more debt on the bond market, and whether they were able to do so with better contract terms.Footnote 30

6.1 E&S performance and bond originations during the financial crisis

To investigate bond originations on the primary market during the financial crisis, we use sample selection criteria similar to those described in Sect. 2 for secondary market bond trades. From Mergent FISD we obtain origination data for bonds that were issued between January 2007 and September 2019 by U.S. domiciled and incorporated publicly listed firms, excluding bonds with non-standard features. This procedure yields 5,797 new issues by 868 firms. After merging these data with annual fundamentals and market data from Compustat and CRSP, respectively, our resulting bond-origination sample for issuers with an E&S rating in 2006 contains 3,606 corporate bonds issued by 406 firms.

We present summary statistics for the variables used in our bond origination estimations in Table 8. The firm characteristics are for the fiscal year-end prior to the year of the bond issue. The average issue size is 3.4% of assets with a median of 2.1%. The bond proceeds average $834 million for a maturity of 8.3 years. The mean credit spread for new bond issues is 1.61%.

We first examine whether high-E&S firms were able to raise more debt in the primary market during the crisis by estimating the following regression for all issuing firms:

where Issueijt is defined as the offering amount scaled by total assets (firms that do not make an initial or seasoned public bond offering are excluded from this analysis), and Zit-1 is a (L×1) vector of lagged firm-level controls that are typically used in studies on new bond issuance (e.g., Leary and Roberts 2005; Badoer and James 2016). Specifically, we control for Market equity, Book-to-market, Profitability, Debt-to-capitalization, Cash holding, Tangibility, Capital expenditure, Dividend indicator, and Investment-grade indicator. We also include firm and time (quarter) fixed effects. As with earlier estimations, we update the firm-level variables three months after a firm’s fiscal year-end, and we double cluster standard errors at the firm and time level. As in Eq. (2), the main effect for the E&S index, measured at the end of 2006, is not included because it is subsumed by the firm fixed effect.

Table 9 contains the estimation results. We report models for the full sample as well as for nonfinancial and financial firms separately. Models (1), (3), and (5) include only the pre-crisis E&S index interacted with the crisis and post-crisis dummies and the fixed effects as explanatory variables, while models (2), (4), and (6) include all control variables. For the full sample, estimation results from models (1) and (2) indicate that high-E&S firms that accessed the corporate bond market during the financial crisis were able to raise more funds than low-E&S firms. In terms of economic significance, based on model (2), increasing the E&S index by one standard deviation (22.1) increases the amount issued as a percentage of assets by 2.9 percentage points during the crisis. The crisis effect is substantial when compared to the average issuance of 3.4% of assets over the entire sample period and 3.1% (untabulated) of assets during the crisis months. Thus, high-E&S firms were essentially able to almost double the size of their bond issues during the crisis relative to the average firm. In the post-crisis period, on the other hand, E&S efforts have no significant impact on the amount of debt raised in the primary bond market.

When studying nonfinancial and financial firms separately in models (3)–(6), we find that the issuance results are solely driven by nonfinancial firms. This is not surprising, given that bond markets were essentially shut for most financial firms during the crisis; only six banks issued bonds during this period.

6.2 E&S performance and contracting terms during the financial crisis

Next, we examine the effect of E&S performance on the pricing and maturity of new bond issues, both during and after the financial crisis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first investigation of the effect of social capital on bond contracting terms. We adopt a similar approach as in the prior tests on the amount raised, and estimate the following specification:

where Issue termijt is the dependent variable of interest. We study both at-issue credit spreads and the maturity of the bond. The vectors of bond and firm controls, Xijt-1 and Zit-1, are the same as in Eq. (2), with the exception of duration, which is not available until several months after the issue date.Footnote 31 As in all models, we also control for firm fixed effects, FFEi, to capture unobservable time-invariant firm-specific determinants of credit risk, and time fixed effects, TFEt. Standard errors are again double clustered at the firm and time level, and the firm’s 2006 E&S index itself is captured by the firm fixed effect.

In Panel A of Table 10, we report the results from estimating Eq. (5) for at-issue credit spreads for our sample of bonds issued from January 2007 to September 2019. We report results for the full sample and for nonfinancial and financial firms separately. Models (1), (3), and (5) include all controls except for the governance pillar score, while models (2), (4), and (6) include governance as a control variable. The effect of the E&S index on at-issue spreads is negative and significant only during the crisis, for both nonfinancial and financial firms, when all controls are included in the model. During this period, the effect is also economically important. For instance, based on the coefficient estimates presented in model (2), a one standard deviation increase in the pre-crisis E&S index (22.1) is associated with 27 basis points lower spread on bonds issued during the crisis period.Footnote 32 The effect of the E&S index on spreads during the post-crisis period is not statistically significant, consistent with our findings for the secondary market. Finally, the difference between the coefficients for the crisis and post-crisis periods is statistically significant for the full sample.

Next, we assess the relation between E&S performance and bond maturity. Imposing a shorter maturity can be viewed as an extreme type of covenant, given bondholders’ limited flexibility in recontracting due to unanimous consent requirements (e.g., Rey and Stiglitz 1993; Berger and Udell 1998). If E&S activities engender trust, high-E&S firms may be able to issue bonds with relatively longer maturities when prevailing trust levels have been eroded. To assess the impact of E&S performance on bond maturity, we regress time-to-maturity on bond- and firm-level controls as in Eq. (5). The results from this estimation are reported in Panel B of Table 10 and show a significant positive relation between the E&S index and bond maturity during the crisis for the full sample and for the subsample of nonfinancial firms. According to model (2), a one standard deviation increase in the pre-crisis level of the E&S index translates into a 17-month-longer time-to-maturity during the crisis (equivalent to over 17 percent of the mean level of maturity in the sample), compared to the pre-crisis period.Footnote 33

In sum, our primary bond market tests provide further evidence that bondholders value the trust earned from building social capital via E&S investments: during the financial crisis, high-E&S firms were able to raise more debt, at more favorable interest rates, and for a longer period of time.Footnote 34

7 Changes in E&S performance over time

Overall, our results provide compelling evidence on the bond market payoffs to firms’ E&S efforts during the financial crisis, when trust in corporations, markets, and institutions declined. Moreover, prior work has pointed out that similar benefits also accrued to shareholders during this period (Lins et al. 2017). In light of this evidence, in this section, we examine whether firms’ E&S performance has changed since the financial crisis. Whether it has or not depends on the extent to which firms have reassessed the benefits associated with E&S investments. After all, E&S efforts are costly, and if the associated benefits materialize only in certain crisis situations, the expected payoffs may not be sufficient to warrant the investment. Learning about the expected payoffs could also be important because firms may not have been fully aware of the payoffs associated with E&S investments until they observed the superior performance of high-E&S firms during the crisis.Footnote 35 Finally, increased pressure from institutional investors (e.g., Dyck et al. 2019) may have led firms to increase their E&S efforts.

To assess whether firms with lower E&S performance during the pre-crisis period subsequently catch up with the top E&S performers, we estimate the following regression over the period 2007–2019:

where E&S index is the measure of a firm’s E&S performance from Refinitiv ESG; Low E&S index is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the firm is in the bottom two terciles in terms of E&S index in 2006; and TFEt denotes yearly time fixed effects that capture the overall trend in E&S performance. We are interested in the coefficients on the interaction terms between the Low E&S index dummy and the time dummies. Model (1) of Table 11 reports the results. Firms in the bottom two terciles of the E&S index start out with E&S scores that are 33 points below those in the top tercile. However, after controlling for the overall trend in E&S index scores, firms in the bottom two terciles catch up and improve their relative scores in all but one of the subsequent years.

Next, we study whether firms adjust their E&S performance when it matters the most in the bond market, namely in the year before they access the primary market. To this end, we augment Eq. (6) with two additional terms: (a) a dummy variable equal to 1 if the firm issues a bond in the subsequent year, and (b) the interaction between this dummy and the Low E&S index dummy. The findings are presented in model (2) of Table 11. While confirming the time trend documented in model (1), the results also illustrate that firms in the bottom two terciles of the E&S index distribution increase their E&S index score by 3.33 points in the year before accessing the primary market.

Altogether, the evidence provided in this section indicates that firms in the lowest terciles of E&S performance prior to the crisis adjusted their E&S activities subsequently to catch up with firms in the top tercile. Moreover, this increase is particularly pronounced in the year before they access the bond market, which suggests that firms learn about the benefits of E&S investments and adjust their E&S performance accordingly.

8 Conclusion

In this paper, we study the importance of social capital, and the trust that it engenders, in the corporate bond market. We employ a firm’s investments in environmental and social activities as a proxy for social capital and find that when the market and the economy faced a severe shock to overall trust during the 2008–2009 financial crisis, high-E&S firms had bond spreads that were substantially lower than those of low-E&S firms. These effects are more pronounced for firms with a higher probability of default, firms with lower asset tangibility, and firms incorporated in states that provide less bondholder protection during insolvency – exactly the types of firms that would have a higher propensity to engage in asset substitution or diversion. For these groups of firms, as well as for firms in the financial services industry, there is also evidence of a continued reduction in credit spreads in the post-crisis period. Our results are also stronger for firms that attach greater importance to E&S activities, as indicated by their aggregate ESG/CSR reporting activities, suggesting that the salience of E&S activities is relevant to bond market investors. Additionally, we show that social capital pays off in periods when there is a loss of trust in specific industries.

In the primary market, we find that nonfinancial high-E&S firms were able to raise more capital on the bond market during the financial crisis period. Among those firms that did access the market, high-E&S firms issued bonds with lower at-issue spreads and for longer maturities.

Consistent with the notion that firms have learned about the benefits of E&S investments over time, we find that firms in the bottom tercile of E&S performance during the pre-crisis period made the largest adjustments to their E&S efforts in subsequent years, particularly before accessing the primary market.

Overall, our results suggest that Earned trust, which is generated through a firm’s investments in social capital, pays off for bondholders when general levels of trust are low. Since firms have discretion in enhancing their social capital through investments in E&S activities, they can exert some influence on their cost of debt, particularly when potential agency frictions with bond investors are higher. Combined with the equity market benefits reported in Lins et al. (2017), our results suggest that a firm’s social capital can increase the enterprise value of a firm when overall trust is low.

Notes

While our measure of social capital is based on the environmental and social elements of ESG, we include governance as a control variable in our estimations. In addition, building social capital through the E&S elements of ESG may itself be indicative of good governance, even if it is not captured by the governance metrics typically employed in governance databases (Dyck et al. 2020).

Our paper documents the role of social capital, as measured by E&S performance, in mitigating the perception of risk taking when there is a systematic shock to trust. Other papers have examined the role of environmental and social responsibility in mitigating the consequences of firm-specific shocks. Using prosecutions of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, Hong et al. (2019) report that more socially responsible firms pay lower fines for bribery when violating the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. Jeffers (2015) finds that officials are more lenient with penalties for Occupational Safety and Health Administration violations ascribed to high-E&S firms. Albuquerque et al. (2019) model corporate social responsibility as a product differentiation strategy that allows firms to benefit from higher profit margins, which lessens systematic risk.

In a similar vein, Guiso et al. (2004) show that in social-capital-intensive regions of Italy, households are more likely to use personal checks and to obtain credit when they demand it.

See also Nofsinger and Varma (2014), who find that socially responsible mutual funds outperformed conventional mutual funds during crisis periods.

The procedure applies to the Enhanced TRACE data both before and after the structural change in the dataset on February 6, 2012. This mainly includes removing retail-sized non-institutional trades (i.e., those with a value below $100,000), dirty prices that include dealer commissions, trades with missing execution time or date or missing trade size, genuine interdealer double counted transactions, trade reversals along with the original trade that is being reversed, trades with missing or negative yields, same-day trade corrections and cancellations, trades outside the secondary market, trades with special conditions defined in FINRA Rule 6730(d)(4)(A), and trades that were an automatic give up.

Specifically, we exclude trades with prices less than $1 or greater than $500, and trades with prices that are 20 percent away from the median of the reported prices in the day or 20 percent away from the previous trading price. We also identify and discard all but one of multiple identical trades that occur at the same time on the same day and at the same quantity, price, and yield on the assumption that they reflect a pass-through transaction.

Using the MSCI ESG KLD STATS database, we find similar results except for the effect of E&S performance on the amount raised in the primary bond market during the financial crisis, which is economically meaningful but statistically insignificant.

The E&S measure based on the MSCI ESG KLD STATS database is constructed as in Lins et al. (2017). The correlation between the two E&S measures is 0.42 for our sample. The correlations for each element are 0.34 for the ‘E’ component and 0.36 for the ‘S’ component. For a detailed analysis of various ESG databases, see Berg et al. (2020).

For more information on the methodology underlying the development of the Refinitiv ESG ratings, see https://www.refinitiv.com/content/dam/marketing/en_us/documents/methodology/esg-scores-methodology.pdf.

Maturity-matched risk-free yields are obtained by linearly interpolating benchmark Treasury yields contained in the Federal Reserve H-15 release for constant maturities.

We obtain credit ratings issued by S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch from Mergent FISD. As in Ellul et al. (2015), to designate a representative rating when an issue is rated by multiple agencies, we first select the S&P rating; if the S&P rating is missing, we use ratings from Moody’s, and if both are missing, we use ratings from Fitch.

Clustering the standard errors at the firm level accounts for firms that have multiple bond issues on the secondary market and is consistent with the firm-level approach noted in Bessembinder et al. (2009).

For more information, see: https://nuscri.org/en/.

In Sect. 4.3, we motivate these tests in greater detail and discuss their relevance during the financial crisis.

The same argument can be made about other corporate financial policies. If firms had been able to predict the financial crisis, they would have entered the crisis with more cash and less debt and would have ensured that their debt was not maturing during the crisis. Indeed, work by Duchin et al. (2010) and Almeida et al. (2012) indicates that high-cash firms, firms with less short-term debt, and firms with less debt maturing during the financial crisis performed better during the crisis and were able to maintain higher levels of investment than other firms. Several other articles have employed ex ante firm characteristics to assess their importance during a crisis (e.g., Beltratti and Stulz 2012; Iyer et al. 2014; Almeida et al. 2015; Albuquerque et al. 2020; Ding et al. 2021).

We start this analysis in 2007 because we study credit spreads after observing the pre-crisis level of the E&S index in 2006.

We also estimate this model without time fixed effects but with dummies for the crisis and post-crisis periods. Our inferences remain unchanged when we employ this alternative specification.

Our 2006 E&S index is time-invariant and is thus absorbed by the firm fixed effects. In untabulated tests, we confirm that our results hold when we use a time-varying, lagged measure of the E&S index.

The standard deviation of the pre-crisis E&S index is 22.16, slightly smaller than the standard deviation of the E&S index for the entire sample period reported in Table 2.

In unreported models, we also allow the effect of the probability of default on spreads to vary during the crisis and post-crisis periods; this does not affect our inferences.

The figure looks similar if we split the sample firms into two groups based on their E&S index on an annual basis.

We verify that our results for nonfinancial firms remain unchanged after removing the two firms in the auto industry that also received government support.

According to the Edelman Trust Barometer, trust in banks was at 69% in early 2008, 36% in early 2009, 29% in early 2010, and 25% in early 2011. Trust started recovering in 2012 at 42%, but has remained below the 2008 level ever since.

We have also investigated whether financial institutions with a higher E&S index were more likely to receive TARP funding and find this to be the case. Increasing the pre-crisis E&S index by one standard deviation leads to an increased likelihood of receiving TARP funding of 9.8 percentage points (after setting the control variables – size, leverage, profitability, volatility, governance score – to their sample means).

Note that we hold the E&S index constant at the end of 2006 in this specification, based on the argument that social capital became more important during the financial crisis but firms were unable to change their E&S investments in the short run. In the long run, however, we expect firms to adjust their E&S investment levels to a new equilibrium. As such, the post-crisis results that we document should be interpreted with caution. In Sect. 7, we discuss firms’ adjustments to their E&S performance in the post-crisis period.

Note that, in general, during our sample period, firms discuss environmental and social performance under the broader remit of their “CSR” activities.

Christensen et al. (2021) draw on the academic literature in accounting, economics, finance, and management and provide an extensive review of studies on the economic and capital market consequences and real effects of ESG activity disclosures.

The loss of trust in oil and gas firms (and in the energy sector more broadly) after the disaster is echoed in a large number of reports and by many commentators. For example, The Report to the President from the National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling indicates that “the disaster in the Gulf undermined public faith in the energy industry…” (p. viii). Charles K. Ebinger, who was a senior fellow in the Energy Security and Climate Initiative at the Brookings Institution, wrote that the event caused “untold damage to the public trust of the entire petroleum industry” (https://www.brookings.edu/blog/planetpolicy/2016/04/20/6-years-from-the-bp-deepwater-horizon-oil-spill-what-weve-learned-and-what-we-shouldnt-misunderstand/).

We are unable to examine the industry-specific loss-of-trust events in the primary market because the number of new bond issues within specific industries during low-trust periods is generally quite small.

Including the first forward-looking duration measure available on the WRDS bond database does not affect our inferences.

The economic effect in terms of percentage spreads appears to be smaller in the primary market than in the secondary market. However, spreads in the primary market are less dispersed, so there is less variation in spreads to explain. The standard deviation of spreads is 1.35% in the primary market and 5.45% in the secondary market. Thus, relative to the standard deviation of the spreads, the economic effect in both markets is similar.

The results on spreads and maturity in the primary market also remain virtually unchanged when we add the issue size relative to assets as an additional explanatory variable to our regression models.