Abstract

Konchitchki and Patatoukas Journal of Accounting and Economics 57 (1-2), 76–88, (2014a) show that aggregate accounting earnings growth predicts future nominal gross domestic product (GDP) growth and that professional macro forecasters do not fully incorporate the information contained in aggregate accounting earnings. Based on results from prior literature, which find that accounting earnings reflect bad economic news in a timelier manner than good news, we condition Konchitchki and Patatoukas’s GDP growth forecast model on the sign of earnings changes. We show that negative changes in aggregate earnings predict future GDP growth while positive changes in earnings do not. Furthermore, we show that professional macro forecasters underreact to the information contained in negative changes in aggregate earnings about future GDP growth. Additional tests suggest our findings are a result of conservative accruals in earnings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

GDP is also used internationally by governments, international investors, and various other bodies, such as Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development,, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank.

Abdalla and Carabias (2017) employ the level of aggregate special items, whereas we employ the change in aggregate special items in our test. Further, they do not control for common leading indicators of economic growth or test whether the association between aggregate special items and GDP growth forecast error is conditional on the sign of aggregate special item changes.

The QFR is a survey of public and private corporations conducted quarterly by the Census Bureau and covers mining; manufacturing; wholesale trade; retail trade; information; and professional, scientific, and technical services. Aggregated shareholder reports sourced from Compustat drive the indicators for the following industries: construction; administrative and waste management services; educational services; health care and social assistance; arts, entertainment, and recreation; and other services.

The notion that systematic news affects firms at the individual level is accepted in the finance literature and underpins the capital asset pricing model (Sharpe 1964; Lintner 1965; Fama and French 2004). The accounting literature links systematic news to firm-level accounting earnings. For instance, Beaver et al. (1970) develop a measure of accounting beta (i.e., the correlation between firm-level accounting earnings and market-level accounting earnings) and show that this measure is relevant to market-determined measures of firm risk. Konchitchki and Patatoukas’s finding that aggregate accounting earnings are helpful in forecasting future GDP growth implies that firm-level earnings change in a systematic way as a function of macroeconomic news (i.e., firm-level earnings changes are not entirely idiosyncratic).

For instance, the value of a factory must be written down, regardless of whether its fair value drops below book value, because of lower aggregate demand (i.e., systematic news) or because of an expiring patent (i.e., idiosyncratic news).

Accounting conservatism is not the only driver of asymmetric timeliness in earnings. For a discussion of how other possible drivers of asymmetric timeliness could affect our results, see Section 6.1.

Following Konchitchki and Patatoukas (2014a), we omit the BEA’s estimate of corporate profits because it is included in the calculation of current period GDP growth, which is already included in the model. Therefore a significant coefficient on aggregate earnings should be interpreted as an incremental effect to that of the BEA’s estimate of corporate profits. Konchitchki and Patatoukas (2015) examine the basic model after controlling for the BEA’s estimate of corporate profits and find consistent results with those of Konchitchki and Patatoukas (2014a). After including BEA corporate profits and allowing it to vary asymmetrically we find similar results. See the web appendix.

Throughout the paper, we follow Konchitchki and Patatoukas (2014a) and use OLS coefficient estimates with standard errors adjusted for both heteroskadasticity and autocorrelation, following Newey and West (1987). The lag length is set equal to three (N0.25, where N, the number of observations used in our regressions, equals 93); see Greene (2011) for details. However, our results are robust to using lag lengths varying from zero to four.

We do not have a theoretical reason to expect a different intercept term when aggregate accounting earnings decline and thus make no prediction for the coefficient on the negative change indicator variable.

Anillowski-Cain and McVay (2016) find that asset write-downs and restructuring comprise most Compustat special items. Specifically, the authors find that special items is comprised from 31%–73% write-downs and from 28%–46% restructuring charges, depending on the subsample examined.

In the web appendix, we report an alternate specification employing I(ΔNIq < 0), rather than decomposing into I(ΔCIq < 0) and I(ΔSPIq < 0), and find similar results. In untabulated results, we find that the correlation between I(ΔNIq < 0) and I(ΔSPIq < 0) is 0.68.

The index incorporates nonfarm payroll employment, the unemployment rate, average hours worked in manufacturing, wages and salaries, housing permits, unemployment insurance claims, manufacturing delivery times, and the interest rate spread. See https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/USSLIND for details.

RECPROB is provided by Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and is obtained from a dynamic-factor Markov-switching model. The model was originally developed by Chauvet (1998). Further detail can be found at the website: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/RECPROUSM156N.

For details, see https://www.bea.gov/national/pdf/NIPAhandbookch1-4.pdf.

3.08 = 0.7408 / 0.2398.

The incremental positive coefficient on negative aggregate earnings changes remains significant in explaining GDP growth up to two quarters ahead.

1.91 = 0.2590 / 0.1359.

Several researchers question the Basu (1997) measure of conservatism, which is widely used in the literature. They question the measure on both theoretical (Schipper 2005; Guay and Verrecchia 2006) and econometric (Dietrich et al. 2007; Patatoukas and Thomas 2011; Lawrence et al. 2013; Patatoukas and Thomas 2016) grounds. Our empirical analysis does not use the Basu specification and is therefore not subject to criticisms of the measure.

Poor contemporaneous operating performance could indicate that a loss has occurred and trigger an asset impairment. In this case, the full capitalized loss will impact accounting earnings, whereas the impact on operating performance will occur over several years.

We use GDI, one of the three theoretical measures of GDP, because it directly incorporates corporate profits. As such, it provides the best sectioning of GDP to examine the direct and indirect explanations.

References

Abdalla, A., & Carabias, J.M. (2017). From accounting to economics: The role of aggregate special items in gauging the state of the economy. Working paper.

Abdih, Y., & Danninger, S. (2018). Understanding U.S. wage dynamics. IMF working paper, WP/18/183.

Ahmed, A., & Duellman, S. (2013). Managerial overconfidence and accounting conservatism. Journal of Accounting Research, 51(1), 1–30.

Anillowski-Cain, Kolev, & McVay. (2016). Qualifying special items: An identification and examination of lower-quality versus higher-quality income-decreasing special items. Working paper.

Ball, R., & Shivakumar, L. (2005). Earnings quality in U.K. private firms: Comparative loss recognition timeliness. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39, 83–128.

Ball, R., & Shivakumar, L. (2006). Role of accruals in asymmetrically timely gain and loss recognition. Journal of Accounting Research, 44(2), 207–242.

Ball, R., Gallo, L.A. & Ghysels, E. (2018). Tilting the evidence: The role of firm-level earnings attributes in the relation between aggregated earnings and gross domestic product. Working paper.

Banker, R., & Byazlov, D. (2014). Asymmetric cost behavior. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 26, 43–79.

Banker, R., Basu, S., Byazlov, D., & Chen, J. (2016). The confounding effect of cost stickiness on conservatism estimates? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 61, 203–220.

Basu, S. (1997). The conservatism principle and the asymmetric timeliness of earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 24, 3–37.

Beaver, W., Kettler, P., & Scholes, M. (1970). The association between market determined and accounting determined risk measures. The Accounting Review, 45(4), 654–682.

Blanchard, O., & Katz, L. F. (1999). Wage dynamics: Reconciling theory and evidence. American Economic Review, 89(2), 69–74.

Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2002). Corporate profits: Profits before tax, profits tax liability, and dividends methodology paper. Washington, D.C.

Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2004). Corporate profits in the GDP accounts. BEA paper series, no. 0040. Washington, D.C.

Bureau of Economic Analysis (2014). NIPA handbook: Concepts and methods of the U.S. National Income and product accounts. Washington, D.C.

Chauvet, M. (1998). An economic characterization of business cycle dynamics with factor structure and regime switching. International Economic Review, 39(4), 969–996.

Chen, C., Young, D., & Zhuang, Z. (2013). Externalities of mandatory IFRS adoption: Evidence from cross-border spillover effects of financial information on investment efficiency. The Accounting Review, 88(3), 881–914.

Collins, D., Hribar, P., & Tian, X. (2014). Cash flow asymmetry: Causes and implications for conditional conservatism research. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 58, 173–200.

Crawley, M. (2015). Macroeconomic consequences of accounting: The effect of accounting conservatism on macroeconomic indicators and the money supply. The Accounting Review, 90, 987–1011.

Dietrich, J., Muller III, K., & Riedl, E. (2007). Asymmetric timeliness tests of accounting conservatism. Review of Accounting Studies, 12, 95–124.

Dutta, S., & Patatoukas, P. (2017). Identifying conditional conservatism in financial accounting data: Theory and evidence. The Accounting Review, 92(4), 191–216.

Elsby, M. W., Shin, D., & Solon, G. (2013). Wage adjustment in the great recession. NBER working paper no. 19478.

Fama, E., & French, K. (2004). The capital asset pricing model: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(3), 25–46.

Faust, J., & Wright, J. (2007). Comparing Greenbook and reduced form forecasts using a large realtime dataset. NBER working paper series, No. 13397. NBER, Cambridge, MA.

Fischer, S., & Merton, S. (1984). Macroeconomics and finance: The role of the stock market. NBER working paper, no. 1291. Cambridge, MA.

Gallo, L., Hann, R., & Li, C. (2016). Aggregate earnings surprises, monetary policy, and stock returns. Journal of Accounting & Economics, 62, 103–120.

Greene, W. (2011). Econometric analysis (Seventh ed.). Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Guay, W., & Verrecchia, R. (2006). Discussion of an economic framework for conservative accounting and bushman and Piotroski. Journal of Accounting & Economics, 42, 149–165.

Henderson, V., Storeygard, A., & Weil, D. (2012). Measuring economic growth from outer space. American Economic Review, 102(1), 994–1028.

Kalay, A., Nallareddy, S., & Sadka, G. (2018). Uncertainty and sectoral shifts: The interaction between firm-level and aggregate-level shocks, and macroeconomic activity. Management Science, 64(1), 198–214.

Konchitchki, Y., &. Patatoukas, P. (2014a). Accounting earnings and gross domestic product. Journal of Accounting and Economics 57 (1–2), 76–88.

Konchitchki, Y., & Patatoukas, P. (2014b). Taking the pulse of the real economy using financial statement analysis: Implications for macro forecasting and stock valuation. The Accounting Review, 89(2), 669–694.

Konchitchki, Y., & Patatoukas, P. (2015). Accounting and the macroeconomy: Accounting quality at the macro level. Working paper.

Kwon Y., K., (2005). Accounting conservatism and managerial incentives. Management Science 51(11), 1626–1632. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1050.0417.

Kwon, Y., Newman, P., & Suh, Y. (2001). The demand for accounting conservatism for management control. Review of Accounting Studies, 6(1), 29–51.

LaFond, R., & Watts, R. (2008). The informational role of conservatism. The Accounting Review, 83, 447–478.

Landefeld, J., Seskin, E., & Fraumeni, B. (2008). Taking the pulse of the economy: Measuring GDP. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(2), 193–216.

Laurion, H., & Patatoukas, P. (2016). From micro to macro: Does conditional conservatism aggregate up in the National Income and product accounts? Journal of Financial Reporting, 1, 21–45.

Lawrence, A., Sloan, R., & Sun, Y. (2013). Non-discretionary conservatism: Evidence and implications. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 56, 112–133.

Lintner, J. (1965). The valuation of risk assets and the selection of risky investments in stock portfolios and capital budgets. Review of Economics and Statistics, 47(1), 13–37.

Mankiw, G. (2011). Principles of economics (Sixth ed.). Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning.

Nallareddy, S., & Ogneva, M. (2017). Predicting restatements in macroeconomic indicators using accounting information. Working paper.

Newey, W., & West, K. (1987). A simple, positive semi-definite, heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent covariance matrix. Econometrica, 55, 703–708.

Nikolaev, V. (2010). Debt covenants and accounting conservatism. Journal of Accounting Research, 48, 51–89.

Pandit, S., Wasley, C., & Zach, T. (2011). Information externalities along the supply chain: The economic determinants of suppliers’ stock price reaction to their customers’ earnings announcements. Contemporary Accounting Research, 28(4), 1304–1343.

Patatoukas, P. (2014). Detecting news in aggregate accounting earnings: Implications for stock market valuation. Review of Accounting Studies, 19(1), 134–160.

Patatoukas, P., & Thomas, J. (2011). More evidence of bias in the differential timeliness measure of conditional conservatism. The Accounting Review, 86, 1765–1793.

Patatoukas, P., & Thomas, J. (2016). Placebo tests of conditional conservatism. The Accounting Review, 91, 625–648.

Raman, K., & Shahrur, H. (2008). Relationship-specific investments and earnings management: Evidence on corporate suppliers and customers. The Accounting Review, 83(4), 1041–1081.

Romer, C., & Romer, D. (2000). Federal reserve information and the behavior of interest rates. American Economic Review, 90, 429–457.

Rouxelin, F., Wongsunwai, W., & Yehuda, N. (2015). Aggregate cost stickiness in GAAP financial statements and future unemployment rate. Working paper.

Roychowdhury, S., & Watts, R. (2007). Asymmetric timeliness of earnings, market-to-book, and conservatism in financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 44, 2–31.

Ryan, S. (2006). Identifying conditional conservatism. European Accounting Review, 15(4), 511–525.

Schipper, K., 2005. Fair values in financial reporting. fars.org/2005AAAFairValueKSchipper.pdf.

Sharpe, W. (1964). Capital asset prices: A theory of market equilibrium under conditions of risk. Journal of Finance, 19(3), 425–442.

Shivakumar, L., & Urcan, O. (2017). Why does aggregate earnings growth reflect information about future inflation? The Accounting Review (forthcoming).

Tan, L. (2013). Creditor control rights, state of nature verification, and financial reporting conservatism. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 55, 1–22.

Watts, R. (2003a). Conservatism in accounting, part I: Explanations and implications. Accounting Horizons, 17, 207–221.

Watts, R. (2003b). Conservatism in accounting, part II: Evidence and research opportunities. Accounting Horizons, 17, 287–301.

Zhang, J. (2008). The contracting benefits of accounting conservatism to lenders and borrowers. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 45, 27–54.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kris Allee, John Campbell, Dan Bens, Yaniv Konchitchki, Stacie Laplante, Clive Lennox, Tom Linsmeier, Dan Lynch, Panos Patatoukas, Michael Minnis (2016 FARS discussant), Siew Hong Teoh, Terry Warfied, conference participants at the 2016 FARS mid-year meeting, and workshop participants at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Nanyang Technological University, and the University of Wisconsin-Madison for providing helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 40 kb)

Appendix

Appendix

Variable Definitions. | |

NI q | Aggregate quarterly net income [NIQ] deflated by sales [SALEQ]. Firm-level sales-deflated quarterly net income is value-weighted by beginning of quarter market value of equity obtained from the CRSP monthly stock file [prc x shrout]. |

ΔNIq: | The year-over-year change in value-weighted sales-scaled quarterly earnings. |

I(ΔNIq < 0) | An indicator variable that takes on a value of 1 when ΔNIq is negative and 0 otherwise. |

CI q | Aggregate quarterly core income, which equals net income [NIQ] before special items [SPIQ] deflated by sales [SALEQ]. Firm-level sales-deflated core income is value-weighted by beginning of quarter market value of equity obtained from the CRSP monthly stock file [prc x shrout]. |

ΔCI q | The year-over-year change in value-weighted sales-scaled quarterly core income. |

SPI q | Aggregate quarterly special items [SPIQ] deflated by sales [SALEQ]. Firm-level sales-deflated quarterly special items are value-weighted by beginning of quarter market value of equity obtained from the CRSP monthly stock file [prc x shrout]. |

ΔSPI q | The year-over-year change in value-weighted sales-scaled quarterly special items. |

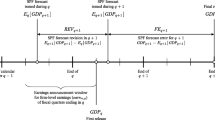

G q | The advance estimate of nominal GDP growth for quarter q, obtained from the real-time data set for macroeconomists available from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. |

G q + 1 | The final estimate of nominal GDP growth for quarter q + 1, obtained from the real-time data set for macroeconomists available from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. |

E q (G q + 1 ) | The mean consensus Society of Professional Forecasters’ forecast of nominal GDP growth for quarter q + 1, which is available from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. |

YIELD q | The yield on the one-year constant-maturity Treasury bill (T-bill) measured one month after quarter q ends. This item is obtained from the Federal Reserve Board’s H15 Report. |

SPREAD q | The yield on the 10-year constant-maturity Treasury bond minus the yield on the one-year constant-maturity T-bill measured one month after quarter q ends. This item is obtained from the Federal Reserve Board’s H15 Report. |

RETURN q | The quarterly buy-and-hold stock market return are from the CRSP Monthly Index File. |

ΔHSTART q | The quarterly change in housing starts. Housing starts data is downloaded from Real-Time Data Research Center, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. |

ΔCPI q | The quarterly change in consumer price index (CPI). CPI is downloaded from Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis’s website. |

ΔCCI q | The quarterly change in consumer confidence index. The consumer confidence index (CCI) for the United States is based on households’ plans for major purchases and their economic situation, both currently and their expectations for the immediate future (https://data.oecd.org/leadind/consumer-confidence-index-cci.htm). |

ΔUNRATE q | The quarterly change in unemployment rate. Unemployment data is obtained from Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. |

IPG q | The quarterly growth in industrial production is obtained from Real-Time Data Research Center, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. |

ΔLI q | The quarterly change in leading index. Leading index for the United States is downloaded from Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis’s website. |

FEDFUNDS q | The federal funds rate is obtained from the Federal Reserve Board’s H15 Report. |

RECPROB q | The probability of a U.S. recession is downloaded from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis’s website. |

GDIq | The quarterly change in the wages and salaries (GDI) component of Gross Domestic Income. |

WSDq | The quarterly change in the wages and salaries disbursements (WSD) component of Nominal Personal Income. |

EMPLOYq | The quarterly change in the total number of employees of nonagricultural payrolls (EMPLOY). |

HOURSq | The quarterly change in the Bureau of Labor Statistics’s index of aggregate weekly hours (HOURS). |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gaertner, F.B., Kausar, A. & Steele, L.B. Negative accounting earnings and gross domestic product. Rev Account Stud 25, 1382–1409 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-020-09536-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-020-09536-x