Abstract

The relationship between (a) private and public equity market valuations and (b) financial statement information is examined for a sample of 502 venture capital backed companies from six different industries over the 1993–2003 period. Financial statement information explains a sizable component of the levels of and changes in valuation in both the Pre-IPO and Post-IPO periods. The findings support prior research for Post-IPO companies that revenues are value enhancing and costs are value diminishing. For the Pre-IPO period, we find that cost of sales; sales, marketing, general and administrative; and research and development are value enhancing—even when revenues are included in the analysis. This is consistent with costs incurred by early-stage, venture-backed companies having a strong “investment aspect” as the companies build a platform/infrastructure to grow revenue and validate their business model(s). We document the growth of early stage companies for revenues and costs in both calendar time (by round of private equity financing) and event time (relative to their eventual IPO).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

VentureOne’s Venture Capital Industry Report (2001) for 2000 indicates a growing trend in both the number of deals and amounts invested in venture capital. Specifically, from 1997 to 2000, the total number of deals in the U.S. grew from 1841 to 4107 while the amount invested grew from $11.42 billion to $68.76 billion. The period from 2001 to 2003 witnessed a decline in venture capital funding in each year with $18.9 billion invested in U.S. venture-backed companies in 2003. Venture capital investment increased during 2004 with $20.4 billion invested in 2,067 deals. (Jeffers and O’Sullivan, 2005).

Privately held venture-backed companies typically make heavy use of options. The price of the security underlying the option (i.e., the share price of the venture-backed firm) is one of the parameters used to price the option within state-of-the-art option pricing models.

This capital investment aspect for early stage companies has also been addressed in the economics literature (Jovanovic, 2005). This author models how P/E ratios for pre-revenue stage industries (“start-up”) are much larger than P/E ratios after the industry moves to the sales stage (“maturity”).

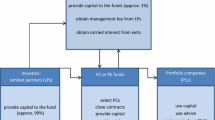

Venture-backed private companies raise financing via a negotiation between the management/board of the early stage (investee) company and one or more venture capital (investor) companies. Two key issues in this negotiation are the valuation of the investee company at the time new financing is arranged (termed pre-money valuation) and the amount of financing to be provided by the investor. The first (second, third,...) round of private funding is (are) referred to as Series A (B,C,...). The pre-money valuation plus the amount of new financing is known as the post-money valuation of the investee company. We refer to the various rounds of financing as, respectively, Series A, Series B, Series C, etc. We adopt this terminology, in part, to avoid confusion when we discuss our results in event time (e.g., −1, 0, +1) versus calendar time (e.g., Series A, B, C). In addition, this terminology is fairly standard in the entrepreneurial finance literature.

The Services classification includes information services, consumer and business services, and healthcare services.

Cochrane (2005) provides a discussion of this bias. Companies that exit via Pre-IPO acquisition are also excluded from our sample.

The top 10 in market capitalization 3 months after their IPO are Akamai Technologies ($30.305 billion), Sycamore Networks ($30.204 billion), Juniper Networks ($17.673 billion), Foundry Networks ($17.044 billion), CommerceOne ($14.731 billion), FreeMarkets ($11.993 billion), InterNAP Networks ($11.426 billion), eBay ($9.711 billion), Vignette ($9.706 billion), and Red Hat ($9.306 billion).

We were able to assess the severity of missing observations in the companies’ funding/valuation sequence in the VentureOne database by tracking the company from its start date through its IPO and counting the number of Series in between. This analysis revealed that for our sample of companies, there were fewer than 40 missing data points (representing approximately 1.6% of the total VentureOne data points) for intermediate rounds of financing.

In the Pre-IPO period, private equity market values on the date of the financial statements (i.e., December 31st for calendar year companies) are derived using the interpolation method. Following Hand (2005), as well as much of the value relevance literature (e.g., Barth, Beaver, and Landsman, 1996), we use public equity market values 3 months after the date of the financial statements (i.e., March 31st for calendar year companies).

We also included an industry specific private equity index in the Pre-IPO and Post-IPO analyses. The index was constructed from the median company value by year, by industry as reported by VentureOne. Inclusion of this variable did not significantly increase the adjusted-R2 nor did it change the inferences drawn about the accounting variables in this study.

This is expected to be the case more so if more than 6 months have elapsed between the date of the financial statements and first round of funding after that date. In this case, the round of financing would be closer (in calendar time) to the next set of financial statements, but would nevertheless be paired with the earlier set of financial statements.

Inferences are unaffected by using the interpolated equity value 3 months after the financial statement date. Use of equity value at a date after the financial statement date is standard in research that examines publicly traded equities in order to ensure that market participants have access to the company financial statements. This is expected to be less of an issue with venture-backed securities where equity investors typically have real-time access to the investee’s financial results.

One drawback of the interpolation method relative to the matching method is that it requires funding information both prior to and following the financial statement date. If, for example, financial statements are produced prior to a company’s first round of venture capital funding, then that set of financial statements is not useable under the interpolation method.

This model is similar to the main specification in Hand (2005). The model includes total assets of the company—decoupled into cash and non-cash assets—and long-term liabilities. These three categories collectively account for most of the balance sheet value in our sample companies. In addition, the three income statement cost variables—COS expense; SMG&A expense; and R&D expense—are the three largest cost items for our companies.

Using the interpolated methodology, SERIES is the most recent series of funding of company i preceding time t.

Using the interpolated methodology, DILUTE is the equity dilution that occurred at the most recent series of funding of company i preceding time t. It should also be noted that our measure of equity dilution is a proxy variable since we measure equity dilution as the amount of funding over the pre-money valuation at a given round of funding. This measure does not consider any additional stock options that are issued at the time of the funding, which is typical in venture-backed companies. This information is not available for our sample firms so we instead rely on our proxy.

To the extent there are other liabilities, or other expenses not included in Equation (1), then the disaggregation of equity and net income, respectively, is incomplete. These omitted items, however, are relatively small in magnitude compared to the items included in Equation (1) for our sample.

Disaggregating net income into its accrual and cash flow components is becoming increasingly popular in the accounting literature. For example, Barth, Beaver, Hand, and Landsman (2004) disaggregate total accruals into various accrual accounts for the purpose of predicting equity values within an Ohlson (1995) framework.

The SERIES and DILUTE variables in Equation (1) do not appear in the Post-IPO model.

An alternative approach to dealing with non-linearities is to transform some or all of the dependent and independent variables. Hand (2005) adopts a log-linear specification in which the variables are replaced with their natural logarithm.

The category “cash” also includes cash equivalents.

In addition, in the private equity market, there could be signaling implications of cash balances in that a higher cash balance (generated either through operations or financing) would signal to potential venture investors that the companies investment opportunities are attractive enough to have secured capital from other investors.

Relative to revenues, cost of goods sold, SG&A, and R&D are roughly 63, 48, and 33% of total revenues for the pooled sample of companies in the Pre-IPO period. In the 3 years following the IPO, these three expense categories are 66, 64, and 19% of total revenues, respectively.

See, for example, Penman and Yehuda (2004) in which net income is disaggregated into revenues and cost of goods sold. In a “levels” regression of price on revenue and cost of goods sold, a positive and negative coefficient (both significant), respectively, obtain. This results also holds for a “changes” regression of return on change in revenue and change in cost of goods sold. In addition, Ohlson and Penman (1992) regress returns on the various components of earnings. They find that “the signs are...correct; income items have positive (estimated) coefficients, whereas expense items have negative coefficients.”

Note that Equation (1) has indicator variables for Series B to Series G+. Thus, the coefficients on these variables are interpreted as the contribution of a particular funding series incremental to Series A financing. That is, Series A is reflected in the intercept of the regression equation.

The sample companies all successfully completed an IPO, which potentially induces a survivorship bias in our data. This bias would predict that private equity market valuations are increasing in the rounds of funding. However, in the Appendix A we show (using an expanded database) that private equity market valuations are also increasing in the round of funding for companies that do not (or have not yet) completed an IPO.

An untabulated correlation matrix reveals that the variables in their first-difference form are much less correlated than in their levels form. This holds for both Pearson product-moment correlation as well as Spearman rank-order correlation. The latter is more appropriate in this analysis, since descriptive statistics suggest that the variables are far from normally distributed.

The series indicators and the equity dilution independent variables are also are omitted because these variables take their value at a given round of financing. Unlike financial statement and certain non-financial statement variables (such as the number of patents), these variables lack meaning in annual differences.

Similar to the levels specifications, the changes specifications are also estimated using a rank regression approach. For the changes specifications, the change in the variables is first computed (either scaled or unscaled) and the change is then ranked. This is different than using the change in the rank from year to year. Rank regression requires that the variable lie in the interval [1,n] where n is the number of observations. This will not always be the case with the latter approach (i.e., the change in the rank), but will be the case with the former approach (i.e., the rank of the change). For further details, see Iman and Conover (1979).

Christie (1987) argues that beginning of period equity valuation is the proper deflator with respect to equity valuation. This result is expected to be applicable in a private equity setting.

Aboody, Barth, and Kasznik (2004) is a good example of a research design that features both a levels and a changes specification in a value relevance context. Consistent with Christie (1987), the independent variables in their returns regression are deflated by beginning of period market capitalization.

Significance refers to statistical significance at the 5% level or less using a one-sided test for signed predictions and a two-sided test in other cases. Since the distribution of the parameters is unknown, all results were replicated using (and are robust to) bootstrapped standard errors.

We extended Model 1(A) in Table 3 for the interpolation method to include an extra variable that interacts COS (COS) and Firm Age. This estimated coefficient on this interaction variable was −.50 (t=−3.68), which is consistent with the positive correlation between equity value and COS declining as a firm gets older. All other inferences were unaffected by the inclusion of this interaction variable.

We re-estimated Equation (1) for our subsample of biotech firms in the Pre-IPO period. The results (untabulated) indicate that the estimated coefficients on successive financing rounds, although generally positive, are all insignificant. This result is further evidence that biotech companies may systematically differ from other companies in our sample.

The specifications were also tested using the number of patents granted instead of the number of patent applications. These two numbers are highly correlated—Pearson product-moment correlation of .90 and Spearman rank order correlation of .77. Inferences are unaffected by the inclusion of patents granted instead of patent applications.

One potential explanation for this result is the importance of “time-to-exit” for venture capitalists. This metric captures the time elapsed between investment in the start-up and when the investor recoups his investment through either the sale of the company or a public offering of the company’s shares. Holding the other variables in the equation fixed, the more time elapsed since the company’s inception, the longer the time-to-exit for the venture capitalists (and the lower their internal rate of return on their investments).

We re-estimated Model 2A in Table 3 to exclude observations after December 31, 2000 to probe whether the negative coefficients on the IPO+2 and IPO+3 indicator variables are due to clustering of observations when there was a sustained decline in technology stock prices. For the reduced sample of 767 observations (vis-à-vis 1231 in Table 3), the coefficients were −.026 (t = −8.22) for IPO + 2 and −.25 (t = −5.15) for IPO + 3. This result is consistent with the “IPO puzzle” reported by Loughran and Ritter (1995).

The Spearman correlation between change in revenue and change in COS is .70 for our Pre-IPO sample and .76 for the Post-IPO period.

The IPO Puzzle refers to the underperformance of companies following an IPO of their equity. Loughran and Ritter (1995) document that for their sample of 4753 companies with an IPO during 1970–1990, the average return to investors was only 5% per year in the 5-year period following their IPO. Teoh, Wong, and Rao (1998) document evidence that IPO firms tend to have high earnings and abnormal accruals in the year of their IPO, which suggests that earnings management is one possible explanation for the subsequent underperformance of IPO shares.

References

Aboody, D., Barth, M., & Kasznik, R. (2004). SFAS No. 123 Stock based compensation expense and equity market values. The Accounting Review, 79, 251–275

Amir, E., & Lev, B. (1996). Value-relevance of nonfinancial information: The wireless communications industry. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 22, 3–30

Barth, M., Beaver, W., Hand, J., & Landsman, W. (2004). Accruals, accounting-based valuation models, and the prediction of equity values. Working Paper, Stanford University.

Barth, M., Beaver, W., & Landsman, W. (1996). Value-relevance of banks’ fair value disclosures under SFAS No. 107. The Accounting Review, 71, 513–537

Barth, M., Clement, M., Foster, G., & Kasznik, R. (1998). Brand values and capital market valuation. Review of Accounting Studies, 3, 41–68

Cochrane, J. (2005). Risk and return of venture capital. Journal of Financial Economics, 75, 3–52

Christie, A. (1987). On cross-sectional analysis in accounting research. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 9, 231–258

Davila, A., & Foster, G. (2005). Management accounting systems adoption decisions: Evidence and performance implications from startup companies. The Accounting Review, 1034–1068.

Davila, A., Foster, G., & Gupta, M. (2003). Venture capital financing and the growth of startup companies. Journal of Business Venturing, 18, 689–708

Gompers, P., & Lerner, J. (2000). Money chasing deals?: The impact of fund inflows on the valuation of private equity investments. Journal of Financial Economics, 55, 281–325

Hand, J. (2004). Determinants of the round-to-round returns to Pre-IPO venture investments in U.S. Biotechnology Companies. Working Paper, University of North Carolina.

Hand, J. (2005). The value relevance of financial statements in the venture capital market. The Accounting Review, 80, 613–648

Heesen, M. (2004). Independence of the Financial Accounting Standards Board. Congressional Testimony Federal Document Clearing House, Congressional Information Service, Inc. April 20, 2004.

Hellman, T, & Puri, M. (2000). The interaction between product market and financing strategy: The role of venture capital. Review of Financial Studies, 13, 959–984

Hellman, T., & Puri, M. (2002). Venture capital and the professionalization of startup companies: Empirical evidence. Journal of Finance, 57, 169–197

Houlihan Valuation Advisors/Venture-One. (1998). The pricing of successful venture-backed high-tech and life-sciences companies. Journal of Business Venturing, 13, 333–351

Iman, R., & Conover, W. (1979). The use of the rank transform in regression. Technometrics, 21, 499–509

Jeffers, M., & O’Sullivan, C. (2005). U.S. Venture-Capital Investment Increases to $20.4 billion in 2004 in first year-over-year increase since 2000. Press release VentureOne and Ernst & Young LLP, July 21, 2005

Jovanovic, B. (2004). The pre-producers. Working Paper, New York University

King, B. (1996). Market and industry factors in stock price behavior. Journal of Business, 39, 139–190

Landsman, W., & Magliolo, J. (1988). Cross-sectional capital market research and model specification. The Accounting Review, 63, 586–604

Lerner, J. (1994). The importance of patent scope: An empirical analysis. RAND Journal of Economics, 25, 319–333

Lev, B., & Sougiannis, T. (1996). The capitalization, amortization, and value-relevance of R&D. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 21, 107–138

Loughran, T., & Ritter, J. (1995) the new issue puzzle. Journal of Finance, 50, 23–51

Ohlson, J. (1995) Earnings, book values, and dividends in equity valuation. Contemporary Accounting Research, 11, 661–687

Ohlson, J., & Penman, S. (1992). Disaggregated accounting data as explanatory variables for returns. Journal of Accounting, Auditing, and Finance, 7, 553–573

Penman, S., & Yehuda, N. (2004). The pricing of earnings and cash flows and an affirmation of accrual accounting. Working Paper, Columbia University.

Sahlman, W. (1993). Aspects of financial contracting in venture capital. The new corporate finance: Where theory meets practice (pp. 229–242). McGraw Hill, New York

Seppa, T., & Laamanen, T. (2000). Valuation of venture capital investments: empirical evidence. Working paper version 2000-06-28.

Teoh, S., Wong, T., & Rao, G. (1998). Are accruals during initial public offerings opportunistic? Review of Accounting Studies, 3, 175–208

VentureOne. (2001). Venture capital source book. San Francisco, CA: Venture Corp.

White, H. (1980). A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica, 48, 817–838

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank John Gabbert from VentureOne for providing key data that made this project possible and the Center for Entrepreneurial Studies (CES), Graduate School of Business, Stanford University for their financial support. The support of Irv Grousbeck, Chuck Holloway, Garth Saloner, and Linda Wells at CES is appreciated. The research assistance of Jakub Wilsz, Nicole Ang, Nicole Bastian, Qintao Fan, Barbara Lubben, and Richard Price in constructing the database used in this research was invaluable. The comments of John Hand on an earlier draft and participants at seminars at Stanford University, Australian Graduate School of Management, and The University of Sydney were of much assistance in our research. We also appreciate the comments of an anonymous referee and Charles Lee (the editor).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

Research inferences and time-period/survivorship issues

Our research examines 502 venture-backed companies that completed an IPO in the U.S. capital markets in the 1996–2000 period. There are two key restrictions as regards generalizing from our results to the broader universe of all venture-backed companies in the U.S.:

-

(a)

The sample restriction to only venture-backed companies that completed an IPO, and

-

(b)

The 5 year time-period restriction to 1996–2000.

This Appendix A examines a broader VentureOne database that covers over 13,000 venture-backed companies over the 1988 to early 2005 period.

Table A.1 reports the median pre-money valuation and median amount raised for rounds A to E for the expanded database according to (1) the time period of the last observation in the database and (2) whether the company completed an IPO. If the company completed an IPO, then the year of the last observation will correspond to the year of the IPO. If, however, the company did not complete an IPO, then the year of the last observation represents one of the following: the year that the company was acquired, the year of the round prior to the company going out of business (e.g., filing for bankruptcy), the year of the round prior to VentureOne being unable to contact the company, or (if the company is still in business) the year of the most recent round of funding. This classification for non-IPO companies makes the results of the different sub-periods more comparable to those for companies that complete an IPO. The numbers of companies in each of the sub-groups are:

1996–2000 | Non-1996–2000 | |

|---|---|---|

IPO | 916 | 723 |

Non-IPO | 4,169 | 7,951 |

Table A.1 reveals that pre-money valuations increase monotonically for both IPO and non-IPO companies during both the 1996–2000 and the non-1996–2000 subperiods. This result holds when the data are grouped according to time period and IPO-status as well. This finding provides support for our research prediction that valuations are increasing in the rounds of funding. It also illustrates that companies—both those that complete an IPO and those that do not—tend to experience increases in valuations between subsequent rounds. Companies that do not make an IPO exit from the database in a given time period may have alternate exits in that same time period (via a trade sale, a merger, or a company windup/dissolution) or may remain as a private venture-backed company in the database.

Table A.2 reports correlations (both Spearman rank-order and Pearson product-moment) between the level of valuation and revenue and the change in valuation and the change in revenue. To parallel our main analysis, we report the correlation using the pre- and post-money values from the matching method (i.e., the valuation of the next round subsequent to the date of the financial statements to which the revenue relates), the interpolated company value, and the annual change in revenue. We report the level of significance and the number of observations below the correlations. The results reveal that there is a positive and statistically significant correlation between the level of private equity value and the level of revenue (using all three measures) for both companies that complete an IPO and those that do not (or have not yet). This holds across both the 1996–2000 subperiod and the non-1996–2000 subperiod. The results in Tables A.1 and A.2 show that our finding a positive association between private equity values and revenues is not unique to companies that complete an IPO during the 1996–2000 period. Instead, this result appears to be robust across (a) companies that exit the venture-backed private equity market via an IPO and those not exiting via an IPO, and (b) companies with an IPO in 1996–2000 vs. an IPO in other years.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Armstrong, C., Davila, A. & Foster, G. Venture-backed Private Equity Valuation and Financial Statement Information. Rev Acc Stud 11, 119–154 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-006-6398-8

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-006-6398-8