Abstract

Purpose

The increased population aging has resulted in a growing need for longitudinal studies about the quality of life among older people. Nevertheless, the results of these investigations could be biased because more disadvantaged people leave the original sample. The purpose of this study is to examine how the selective attrition observed in a panel survey affect multivariate models of subjective well-being (SWB). The question is if we could do reliable longitudinal investigations concerning the predictors of SWB in old age.

Methods

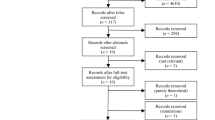

This paper examines attrition in a panel of older people in Chile. Attrition was evaluated in the variables that affect elderly SWB. Probit models were fitted to compare dropouts with nondropouts. Then, multivariate probit models were estimated on satisfaction and depressive symptoms, comparing dropouts and nondropouts. Finally, we compared weighted and unweighted multivariate probit models on SWB.

Results

The attrition rate in 2 years was 38.8%, including deaths and 32.9%, excluding them. Survey dropouts had lower satisfaction but not higher depressive symptoms. Among SWB predictors, people without a partner and with lower self-efficacy abandoned more the study. When applying the Becketti, Gould, Lillard, and Welch test, the probit coefficients of the predictor variables on SWB outcome variables were similar for dropouts and nondropouts. Finally, the comparison of multivariate models on SWB with weighting methods did not find substantial differences in the explanatory coefficients.

Conclusion

Although some predictors of attrition were associated with SWB, attrition did not produce biased estimates in multivariate models of life satisfaction life or depressive symptoms in old age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data and Software Code (in Stata Software) are available on request to mherrepo@uc.cl.

References

Chandola, T., & O’Shea, S. (2013). Innovative approaches to methodological challenges facing ageing cohort studies. National Centre for Research Methods (NCRM) discussion paper report.

Banks, J., Muriel, A., & Smith, J. P. (2011). Attrition and health in ageing studies: Evidence from ELSA and HRS. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies. https://doi.org/10.14301/llcs.v2i2.115.

Chatfield, M. D., Brayne, C. E., & Matthews, F. E. (2005). A systematic literature review of attrition between waves in longitudinal studies in the elderly shows a consistent pattern of dropout between differing studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 58, 13–19.

Bhaskaran, K., & Smeeth, L. (2014). What is the difference between missing completely at random and missing at random? International Journal of Epidemiology, 43, 1336–1339.

Iglesias, K., Gazareth, P., & Suter, C. (2017). Explaining the decline in subjective well-being over time in panel data. In: G. Brulé & F. Magging (Eds.), Metrics of subjective well-being: Limits and improvements. Springer, pp 85–105.

Lacey, R. J., Jordan, K. P., & Croft, P. R. (2013). Does attrition during follow-up of a population cohort study inevitably lead to biased estimates of health status? PLoS One, 8(12), e83948.

Groves, R. M., & Peytcheva, E. (2008). The impact of nonresponse rates on nonresponse bias: A meta-analysis. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 72, 167–189. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfn011.

Ahern, K., & Le Brocque, R. (2005). Methodological issues in the effects of attrition: Simple solutions for social scientists. Field Methods, 17, 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X04271006.

Li, C. P. (2017). Selective attrition in life satisfaction among elderly people: The harmonisation of longitudinal data. EDP Sciences, p. 01059.

Potočnik, K., & Sonnentag, S. (2013). A longitudinal study of well-being in older workers and retirees: The role of engaging in different types of activities. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86, 497–521.

Rafnsson, S. B., Shankar, A., & Steptoe, A. (2015). Longitudinal influences of social network characteristics on subjective well-being of older adults: Findings from the ELSA study. J Aging Health, 27, 919–934. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264315572111.

Tampubolon, G. (2015). Delineating the third age: Joint models of older people’s quality of life and attrition in Britain 2002–2010. Aging & Mental Health, 19, 576–583.

Ward, M., McGarrigle, C. A., & Kenny, R. A. (2019). More than health: Quality of life trajectories among older adults—Findings from The Irish Longitudinal Study of Ageing (TILDA). Quality of Life Research, 28, 429–439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1997-y.

Brett, C. E., Dykiert, D., Starr, J. M., & Deary, I. J. (2019). Predicting change in quality of life from age 79 to 90 in the Lothian Birth Cohort 1921. Quality of Life Research, 28, 737–749. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-2056-4.

Palgi, Y., Shrira, A., & Zaslavsky, O. (2015). Quality of life attenuates age-related decline in functional status of older adults. Quality of Life Research, 24, 1835–1843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-0918-6.

Webb, E., Blane, D., McMunn, A., & Netuveli, G. (2011). Proximal predictors of change in quality of life at older ages. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 65, 542–547.

Kempen, G. I., & van Sonderen, E. (2002). Psychological attributes and changes in disability among low-functioning older persons: Does attrition affect the outcomes? Journal of clinical epidemiology, 55, 224–229.

Yu, B., Steptoe, A., Niu, K., et al. (2018). Prospective associations of social isolation and loneliness with poor sleep quality in older adults. Quality of Life Research, 27, 683–691. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1752-9.

Goodman, J. S., & Blum, T. C. (1996). Assessing the non-random sampling effects of subject attrition in longitudinal research. Journal of Management, 22, 627–652.

Rothenbühler, M., & Voorpostel, M. (2016). Attrition in the Swiss Household Panel: Are vulnerable groups more affected than others? In M. Oris, C. Roberts, D. Joye, & M. Ernst Stähli (Eds.), Surveying human vulnerabilities across the life course (pp. 221–242). Switzerland: Springer Nature.

Vega, S., Benito-León, J., Bermejo-Pareja, F., et al. (2010). Several factors influenced attrition in a population-based elderly cohort: Neurological disorders in Central Spain Study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63, 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.03.005.

Behr, A., Bellgardt, E., & Rendtel, U. (2005). Extent and determinants of panel attrition in the European Community Household Panel. European Sociological Review, 21, 489–512.

Satherley, N., Milojev, P., Greaves, L. M., et al. (2015). Demographic and psychological predictors of panel attrition: Evidence from the New Zealand attitudes and values study. PLoS One, 10(3), e0121950.

Uhrig, S. N. (2008). The nature and causes of attrition in the British Household Panel Survey. Essex: Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Essex Colchester.

Nicole, W., & Mark, W. (2013). Re-engaging with survey non-respondents: Evidence from three household panels. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 177, 499–522. https://doi.org/10.1111/rssa.12024.

Voorpostel, M. (2009). Attrition in the Swiss Household Panel by demographic characteristics and levels of social involvement. Lausanne: FORS.

Hansen, T., & Slagsvold, B. (2012). The age and subjective well-being paradox revisited: A multidimensional perspective. Norsk epidemiologi, 22, 187–195.

Berg, A. I., Hoffman, L., Hassing, L. B., et al. (2009). What matters, and what matters most, for change in life satisfaction in the oldest-old? A study over 6 years among individuals 80+. Aging & Mental Health, 13, 191–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860802342227.

Zaninotto, P., Falaschetti, E., & Sacker, A. (2009). Age trajectories of quality of life among older adults: Results from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Quality of Life Research, 18, 1301–1309.

Carmel, S., Raveis, V. H., O'Rourke, N., & Tovel, H. (2017). Health, coping and subjective well-being: Results of a longitudinal study of elderly Israelis. Aging & Mental Health, 21, 616–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1141285.

Hajek, A., & König, H. (2019). The role of optimism, self-esteem, and self-efficacy in moderating the relation between health comparisons and subjective well-being: Results of a nationally representative longitudinal study among older adults. British Journal of Health Psychology, 24, 547–570.

Kunzmann, U., Little, T. D., & Smith, J. (2000). Is age-related stability of subjective well-being a paradox? Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence from the Berlin Aging Study. Psychology and Aging, 15, 511.

Jonker, A. A. G. C., Comijs, H. C., Knipscheer, K. C. P. M., & Deeg, D. J. H. (2008). Persistent Deterioration of Functioning (PDF) and change in well-being in older persons. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 20, 461–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03325153.

Neubauer, A. B., Schilling, O. K., & Wahl, H.-W. (2015). What do we need at the end of life? Competence, but not autonomy, predicts intraindividual fluctuations in subjective well-being in very old age. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72, 425–435. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbv052.

Gerstorf, D., Heckhausen, J., Ram, N., et al. (2014). Perceived personal control buffers terminal decline in well-being. Psychology and Aging, 29, 612.

Bowling, A., & Iliffe, S. (2011). Psychological approach to successful ageing predicts future quality of life in older adults. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 9, 13.

Wahrendorf, M., & Siegrist, J. (2010). Are changes in productive activities of older people associated with changes in their well-being? Results of a longitudinal European study. European Journal of Ageing, 7, 59–68.

Huxhold, O., Miche, M., & Schüz, B. (2014). Benefits of having friends in older ages: Differential effects of informal social activities on well-being in middle-aged and older adults. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69, 366–375.

Hillygus, D. S., & Snell, S. A. (2015). Longitudinal surveys: Issues and opportunities. In L. Atkeson & R. Alvarez (Eds.), Oxford handbook on polling and polling methods (pp. 28–52). New York: Oxford Universituy Press.

Brilleman, S. L., Pachana, N. A., & Dobson, A. J. (2010). The impact of attrition on the representativeness of cohort studies of older people. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 10, 71.

Feng, D., Silverstein, M., Giarrusso, R., et al. (2006). Attrition of older adults in longitudinal surveys: Detection and correction of sample selection bias using multigenerational data. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61, S323–S328.

Kuhn, U. (2009). Attrition analysis of income data. Lausanne: FORS.

Matthews, F. E., Chatfield, M., Freeman, C., et al. (2004). Attrition and bias in the MRC cognitive function and ageing study: An epidemiological investigation. BMC Public Health, 4, 12.

Van Beijsterveldt, C., Van Boxtel, M., Bosma, H., et al. (2002). Predictors of attrition in a longitudinal cognitive aging study: The Maastricht Aging Study (MAAS). Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 55, 216–223.

Weuve, J., Tchetgen, E. J. T., Glymour, M. M., et al. (2012). Accounting for bias due to selective attrition: The example of smoking and cognitive decline. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass), 23, 119.

Young, A. F., Powers, J. R., & Bell, S. L. (2006). Attrition in longitudinal studies: Who do you lose? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 30, 353–361.

Weir, D., Faul, J., & Langa, K. (2011). Proxy interviews and bias in the distribution of cognitive abilities due to non-response in longitudinal studies: A comparison of HRS and ELSA. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 2, 170–184. https://doi.org/10.14301/llcs.v2i2.116.

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Biswas-Diener, R., et al. (2009). New measures of well-being. In E. Diener (Ed.), Assessing well-being. The collected works of Ed Diener (pp. 247–266). Dordrecht: Springer.

U. C. & Caja-Los-Andes (2017). Chile y sus Mayores. 10 años de la Encuesta Calidad de Vida en la Vejez UC - Caja Los Andes. Santiago de Chile. https://adultomayor.uc.cl/docs/Libro_CHILE_Y_SUS_MAYORES_2016.pdf.

Carrasco, M., Herrera, S., Fernández, B., & Barros, C. (2013). Impacto del apoyo familiar en la presencia de quejas depresivas en personas mayores de Santiago de Chile. Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología, 48, 9–14.

Hoyl, T., Valenzuela, E., & Marín, P. (2000). Depresión en el adulto mayor: evaluación preliminar de la efectividad, como instrumento de tamizaje, de la versión de 5 ítems de la Escala de Depresión Geriátrica. Revista Médica de Chile, 128, 1199–1204. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0034-98872000001100003.

Herrera, M. S., Barros, C., & Fernández, M. B. (2011). Predictors of quality of life in old age: A multivariate study in Chile. Journal of Population Ageing, 4, 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-011-9043-7.

Dolan, P., Peasgood, T., & White, M. (2008). Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29, 94–122.

Herrera, M. S., Fernández, M. B., & Barros, C. (2014). Older Chileans, quality of life. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 4477–4481). Dordrecht: Springer.

Keng, S.-H., & Wu, S.-Y. (2014). Living happily ever after? The effect of Taiwan’s National Health Insurance on the happiness of the elderly. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 783–808.

Pinquart, M., & Sorensen, S. (2000). Influences of socioeconomic status, social network, and competence on subjective well-being in later life: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 15, 187–224.

Fernández-Ballesteros, R., Dolores Zamarrón, M., & Angel Ruíz, M. (2001). The contribution of socio-demographic and psychosocial factors to life satisfaction. Ageing and Society, 21, 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X01008078.

Chen, G., Gully, S., & Even, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organizational Research Methods, 4, 62–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810141004.

Smilkstein, G. (1978). The family APGAR: A proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. Journal of Family Practice, 6, 1231–1239.

Russel, D., Peplau, L. A., & Cutrona, C. E. (1980). The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 472–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472.

Hughes, M., Waite, L., Hawkley, L., & Cacioppo, J. (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys. Research on Aging, 26, 655–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027504268574.

Perissinotto, C. M., Cenzer, I. S., & Covinsky, K. E. (2012). Loneliness in older persons: A predictor of functional decline and death. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172, 1078–1084. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1993.

Alderman, H., Behrman, J. R., Kohler, H.-P., et al. (1999). Attrition in longitudinal household survey data: Some tests for three developing-country samples. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Outes-Leon, I., & Dercon, S. (2008). Survey attrition and attrition bias in Young Lives. Yong Lives Technical Note, 51.

Becketti, S., Gould, W., Lillard, L., & Welch, F. (1988). The panel study of income dynamics after fourteen years: An evaluation. Journal of Labor Economics, 6, 472–492.

Fitzgerald, J., Gottschalk, P., & Moffitt, R. (1998). An analysis of sample attrition in panel data. The Journal of Human Resources, 33, 251–299.

Razafindratsima, N., & Kishimba, N. (2004). Attrition in the COCON cohort between 2000 and 2002. Population, 59, 357–385. https://doi.org/10.3917/popu.403.0419.

Arif, G. M., & Bilquees, F. (2006). An Analysis of sample attrition in the PSES panel data. Islamabad: Pakistan Institute of Development Economics.

Baulch, B., & Quisumbing, A. (2011). Testing and adjusting for attrition in household panel data. CPRC Toolkit Note.

Pape, A. (2004). How does attrition affect the Women’s Employment Study data. Unpublished manuscript available online at: https://www.fordschool.umich.edu/research/pdf/WES_Attrition-oct-edit.pdf.

Ayala, L., Navarro, C., & Sastre, M. (2006). Cross-country income mobility comparisons under panel attrition: The relevance of weighting schemes. ECINEQ Working Paper 47.

Kalton, G., & Brick, M. (2000). Weighting schemes for household panel surveys. In D. Rose (Ed.), Researching social and economic change. The uses of household panel studies (pp. 96–112). London: Routledge.

Valliant, R., Dever, J. A., & Kreuter, F. (2013). Practical tools for designing and weighting survey samples. New York: Springer.

Nicoletti, C., & Buck, N. (2004). Explaining interviewee contact and co-operation in the British and German household panels. ISER Working Paper Series, 6

Herrera, M. S., Fernández, M. B., & Barros, C. (2017). Estrategias de afrontamiento en relación con los eventos estresantes que ocurren al envejecer. Ansiedad y Estrés, 24, 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anyes.2017.10.008.

Gerry, C., & Papadopoulos, G. (2015). Sample attrition in the RLMS, 2001–10. Economics of Transition, 23, 425–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecot.12063.

Rindfuss, R. R., Choe, M. K., Tsuya, N. O., et al. (2015). Do low survey response rates bias results? Evidence from Japan. Demographic Research, 32, 797–828. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2015.32.26.

Jacomb, P. A., Jorm, A. F., Korten, A. E., et al. (2002). Predictors of refusal to participate: A longitudinal health survey of the elderly in Australia. BMC Public Health, 2, 4.

Matthews, F. E., Chatfield, M., & Brayne, C. (2006). An investigation of whether factors associated with short-term attrition change or persist over ten years: Data from the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study (MRC CFAS). BMC Public Health, 6, 185.

Voorpostel, M., & Lipps, O. (2011). Attrition in the Swiss Household Panel: Is change associated with drop-out? Journal of Official Statistics, 27, 301–328.

Olson, K., & Witt, L. (2011). Are we keeping the people who used to stay? Changes in correlates of panel survey attrition over time. Social Science Research, 40, 1037–1050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.03.001.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Luis Maldonado for his selfless teaching in statistical methods in panel surveys. Nevertheless, he has no responsibility for the analysis and interpretations presented in this study.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant-in-aid for scientific research from the Chilean Government, Conicyt (“Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica”, today it is called “Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo- ANID”), Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (Fondecyt Regular 1171070 and Fondecyt Regular 1120331). The authors declare that they have not received any other funding from any other institution.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by MSH and MBF. Statistical analysis was performed by DD and MSH. All authors participated in the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Ethical approval

All procedures, including the informed consent process, were conducted following the ethical standards of the research with humans in Chile and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration of 197, as revised in the 64ª Asamblea General, Fortaleza, Brasil, October 2013.

The project had an ethical follow-up at all stages, being approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (7 September 2016).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Herrera, M.S., Devilat, D., Fernández, M.B. et al. Does the selective attrition of a panel survey of older people affect the multivariate estimations of subjective well-being?. Qual Life Res 30, 41–54 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02612-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02612-4