Abstract

Objectives

Niemann-Pick disease type C (NPC) is a rare life-limiting disease for which there is no cure. No scales currently exist to measure the impact of medication, physical therapy or clinical trials. The aim of this study was to develop age-appropriate Quality-of-Life (QoL) scales to measure the impact of NPC on children and adults.

Design

Scale development study using a phenomenological approach to data generation and analysis.

Methods

Fourteen interviews were conducted with people living with NPC and/or their parents/carers. Themes were generated and examined against an existential-phenomenological theory of wellbeing. A matrix was constructed to represent the phenomenological insight gained on participants’ subjective experiences and a bank of items that were related to their QoL was developed.

Results

NPC quality-of-life questionnaires for children (NPCQLQ-C) and adults (NPCQLQ-A) proxy prototype scales were produced and completed by 23 parents/carers of children (child age mean = 8.61 years) and 20 parents/carers of adults (adult age = 33.4 years). Reliability analysis resulted in a 15-item NPCQLQ-C and a 30-item NPCQLQ-A, which showed excellent internal consistency, Cronbach’s α = 0.925 and 0.947, respectively.

Conclusion

The NPCQLQ-C and NPCQLQ-A are the first disease-specific QoL scales to be developed for people living with NPC. This novel approach to scale development values the experiential, real life impact of living with NPC and focused on the lived-experiences and impact on QoL. The scales will enable healthcare professionals and researchers to have a better understanding and quantifiable measurement of the impact of living with NPC on a patient’s daily life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Niemann-Pick disease type C (NPC) is a rare, genetic neurovisceral disease with a clinical incidence of approximately 1:100,000 [1, 2]. The clinical features of NPC include progressive loss of vision, hearing, muscle co-ordination and mobility. Cognitive decline leading to early-onset dementia can occur resulting in premature death in most people [2]. Symptoms are heterogeneous and can arise at any point between early childhood and late adulthood and progress at different rates [1]. NPC is classed as a life-limiting condition as there is no cure, and the only approved disease-specific drug available is Miglustat (Zavesca®; Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd), which is offered for the treatment of progressive neurological manifestations [2].

Living with any life limiting disease brings difficulties but living with a rare disease generates unique challenges for both the person diagnosed and their carers, and can be an isolating experience [3]. Bury’s [4] concept of biographical disruption suggested that an individual’s sense of self, social interactions, and daily life are disrupted by the illness experience. Illness can be characterised as a disturbance to the narrative flow of individuals’ lives, and episodes of ill health can represent significant change and can be viewed as a threat to this constructed self-narrative [5]. When related to NPC, a disruption may feel permanent due to there being no cure, never allowing a return to life prior to the diagnosis; thus necessitating a change in a person’s biography and self-concept [4]. Yet, Carel [6] argued that it was possible for one to experience wellbeing in spite of illness. Thus, living with illness does not necessarily mean a wholly negative disruption and instead could be seen as something that could bring positive consequences, self-discovery and self-development [7, 8]. This illustrates the complexity of the illness journey and that there are numerous factors to take into account when considering the impact living with NPC has on a person’s QoL.

The concept of QoL is a highly valued focus of research and consideration within clinical practice. Despite this popularity, the lack of consensus on the definition of QoL is a source of confusion [9]. Arguably one of the most respected definitions of QoL is the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) which describes it as being “individuals’ perceptions of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns” (p. 1404) [10]. It is therefore multi-dimensional in its outworking and is understood as a “broad ranging concept affected in a complex way by the person’s physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs and their relationship to salient features of their environment” (p. 1) [11]. With no qualitative research being conducted on understanding the experiences of living with NPC, it was important to prioritise focus on the “individuals’ perceptions” of what life with NPC means, in order to garner the nuances of the illness experience.

Accomplishing this necessitates an engagement with broader philosophical constructs and frameworks that can be used to understand such phenomena. An interaction with other theories that seek to broaden the scope of enquiry and ask more fundamental questions about how human beings understand the world about them is needed. There is a need to step back from the traditional fragmented components of what makes QoL, and subsequently what are used in QoL measurements and instead start first by considering the depth to what constitutes life in all of its quality from an ontological perspective, an issue deeply embedded in what it means to be human. Arguably a stronger emphasis on the developmental process may provide a more robust basis for QoL scales based on lived-experience in conjunction with theoretical models that aim to provide the fullest explanation possible as to what it is to live with illness.

Todres, Galvin and Dahlberg’s [12] existential-phenomenological theory of lifeworld-led care explores how individuals live in relation to time, space, body, others and mood; a holistic outlook in which human beings understand the world around them. The lifeworld, as introduced by Husserl [13], and Heidegger [14], is a concept that represents the world as meaningful and relational, one that can be experienced and lived [15, 16]. Todres and Galvin [17] discussed six dimensions that represent constituents of the lifeworld, intertwined within one another, yet holding certain nuances of lived experience. The dimensions are temporality, spatiality, intersubjectivity, embodiment, identity and mood (see Table 1 for an explanation of the dimensions of the lifeworld). Arguably, many of the principles within pre-existing QoL domains complement the lifeworld-led care constructs. However, lifeworld-led theory allows for a more open, less-constrained view, which incorporates the shared and unique dimensions of individuals’ experiences that are central to their QoL: something which is particularly important when looking at a rare disease about which we know very little [12].

In order to understand the markers of QoL for people living with NPC, one must explore and understand the impact of living with illness on the lifeworld of a person. As Bunge [18] argued: “A better understanding of the quality of life calls for more intense theoretical and methodological work rather than an increase in the amount of social and environmental statistics… data without ideas are sterile when not misleading” (p. 65). Therefore, the current study sought to develop age-appropriate, disease-specific QoL scales based on the lived experiences of people living with NPC using Todres, Galvin and Dahlberg’s [12] lifeworld-led care theory. These scales would be developed for the assessment of individuals who have NPC to enable healthcare professionals to better engage with patient’s wellbeing and to provide a useful measure of outcome in clinical and drug trials [19].

Methods

NHS ethical approval was granted for this study to enable recruitment from NHS clinics and the NPUK charity (ethics number: 15/WM/0093). Signed informed consent was obtained from all participants. Due to the rarity of the disease, individual participant demographic information has been hidden due to the possibility of identification, but the mean and standard deviation of the ages of the participants has been provided.

Scale development

The process followed gold standard scale development guidelines [20, 21]. A qualitative approach was chosen which aimed to conceptualise ‘quality of life’ from the subjective experiences of people living with NPC, with an exploratory analysis routed in phenomenology. This study interpreted ‘quality’ as being that which helps or prevents people from living an authentic life. Any disruptions to a person’s lifeworld were seen as a key avenue of exploration in how living with NPC may impact upon a person’s QoL. Used as an approach to research, phenomenology provides a way of exploring phenomena holistically as they are experienced in the world. The phenomenon in this study is living with NPC as experienced by people with a diagnosis and their parents or carers. This approach allowed for a deeper understanding of the existential meanings of living with NPC. In conjunction with the use of phenomenology, lifeworld-led theory was drawn upon (see, for example of a similar analysis [22]). Using the elements of the lifeworld deepened the analysis, producing the best possible explanations as to the effects of NPC on all aspects of QoL.

Participants

Fourteen semi-structured interviews were conducted with people diagnosed with NPC and/or parents or carers of people living with NPC (see Table 2 for participant information). Eight parents/carers of children were interviewed and 6 parents/carers of adults. When possible, children or adults with NPC also took part in the interview. One interview took place with an adult with NPC without their parent/carer present. All participants were recruited through the Niemann-Pick UK charity (NPUK), a charity that provides practical support, advice and information for people affected by NPC. Participants were recruited purposively to ensure the sample consisted of a similar ratio of males to females and participants were from across the age range. All were UK residents.

Data collection

An advertisement for the study was published on the NPUK Charity’s social media pages and interested participants contacted the researcher. Written consent was taken from people with NPC who were able to take part in the interview themselves and from the person with NPC’s parents/carers prior to interview. The interview schedule was developed in consultation with parents of children with NPC, and clinicians who work with patients with NPC and with NPUK. Participants were asked to talk about their experiences of living with NPC. Open-ended questions focused on the NPC story starting from diagnosis, moving to how life had changed since receiving this diagnosis. Some examples of these questions are ‘Can you tell me about the diagnosis process and how you felt during it?’ ‘Can you tell me how things are on a daily basis?’ ‘Can you tell me about how living with NPC has impacted upon your life?’ For parents or carers who were interviewed without the person with NPC being present, the researcher asked them to put themselves ‘in the shoes of the person they were caring for’. The schedule was not prescriptive or inclusive but acted as a guide in the interview in order to ensure the aims of the study were met. Interviews were recorded using a Dictaphone and transcribed verbatim.

Qualitative analysis of interviews

In order to ensure the items were age appropriate, data were analysed in two age groups, children with NPC 0–17 years and adults with NPC 18 years and over. The interview data were analysed initially using interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) [23]. IPA is a phenomenological method, but with a focus on hermeneutics which enables one to examine the subjective experience of living with NPC as well as participants’ own sense-making of that experience [23, 24]. IPA usually focuses on first-hand accounts, but in this study we have extended this to incorporate the biographic account of parents’/carers’ meaning-making of the experiences of the person they are caring for. This enabled us to further explore and understand the phenomenon of living with NPC. Transcripts were re-read several times, enabling the researcher to become familiar with the data and to become attuned to the participants’ experiences. Each transcript was annotated in depth, focusing on semantic content and striking language used by the participant, which may be related to the impact of NPC on their QoL. Themes were generated, which focused on the interrelation of patterns in the data by mapping connections between the exploratory notes and the data. Todres, Galvin and Dahlberg’s [12] lifeworld-led theory was then used to further make sense of the inductive themes arising from the IPA analysis. This theory was adopted because of its commitment to describing and understanding the lifeworld in its wholeness, as a set of interrelated dimensions incorporating both wellbeing and suffering. This involved a cyclical dialogue between the themes generated alongside the elements of the lifeworld, thus embedding the inductive analysis within existential-phenomenological theory. Themes and subthemes were explored in more detail by going through each element of the lifeworld using the lens of living with NPC and the impact it may have on QoL. Discussions were held within the research team throughout all phases of analysis so we could be confident that the interpretation of the data produced was the best possible explanation.

Item generation

Due to the neurological effects of NPC on patients, after conducting interviews it was decided that it would be more appropriate to develop all the scales as proxy scales, rather than ones for direct use with the patient as very few people with NPC would be able to answer a QoL questionnaire [25]. From the cyclical process between the IPA analysis and the lifeworld-led theory, a bank of all possible items which were considered to have an effect on an individual’s QoL were noted. This involved the construction of a matrix of all reported themes and subthemes with descriptive summaries/phrases relevant to QoL set against the elements of the lifeworld. Themes and lifeworld elements were cross-compared to produce a list of all potential items that could be used to describe the QoL of someone with NPC. Variations of similarly focused items were worded differently and were kept on the list to establish which item was worded the most appropriately. Examples of items in relation to the lifeworld elements are reported in Table 3 for children and Table 4 for adults. These possible items were then discussed within a team of psychologists, one of which was an expert in scale development and validation, as well as stakeholders who work with NPC patients and families. Similar worded items were omitted as a result of this discussion.

A mixture of closed questions and open-ended questions was developed for the child and adult scales. The open-ended questions were intended to garner a richer perspective on any additional needs of the person with NPC; these questions were optional. All closed items were written as statements with a 5-point Likert response scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The time period that people are asked to reflect over in order to answer the questions is over the course of 4 weeks. As the scales were developed as proxy versions, parents/carers were reminded in the instructions to answer the questions from the perspective of how they felt the one they were caring for would answer; this questionnaire was not assessing their experiences, but the experiences of the ones for whom they were caring. The final child prototype scale (NPCQLQ-C) consisted of 28 items; the adult prototype scale (NPCQLQ-A) consisted of 38 items.

Item reduction and reliability testing

Data collection

Adverts for the study were promoted by NPUK on their social media pages, with the link to the questionnaires, which could be answered using Qualtrics, a secure online survey. The study was also advertised at the NPUK annual conference where paper copies of the questionnaire were available for parents/carers to complete. Paper copies were available on request. The majority (n = 26) of questionnaires were completed at the NPUK conferences, where LA and RK were present. Participants were asked to complete the relevant NPCQLQ scale alongside a demographic questionnaire on both the person with NPC and the parent/carer, to collect information including gender, age, occupation and ethnicity. They were also asked to complete an NPC severity questionnaire, with information such as when NPC was diagnosed, current symptoms and medication. Parents/carers were asked to rate what they felt to be the severity of the condition for the person for whom they were caring (from 0 to 9 with 9 being most severe). Both the demographic and disease severity questionnaires were developed by the research team.

Cognitive interviews

Cognitive interviews with six participants (split equally between parents of children with NPC and carers of adults with NPC) were conducted [21]. The objectives of cognitive interviewing are to determine the appropriateness and comprehension of the items included in the questionnaire, providing insight to the suitability of the questions asked [21]. This process involved LA and RK speaking to the participants, asking them to discuss each item, what it meant to them and whether they were able to answer it on behalf of the person with NPC for whom they were caring. They were also asked if the instructions and rating scales were clear. No changes were made to the instructions and rating scales based on the cognitive interviews. Feedback on items were used for item reduction alongside the statistical analyses (see Results section).

Reliability analysis

Initial item reduction was based on examination of inter-item correlations, floor and ceiling effects and number of missing data points for any item. Internal consistency was assessed by calculating Cronbach’s coefficient alpha for the total scale, to demonstrate the extent to which the items in the scales measure the same concept [26]. Although a usual part of scale development, an exploratory factor analysis was not planned due to the small numbers of participants completing the scales as a consequence of the rarity of the condition.

Results

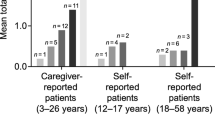

Twenty-three parents/carers completed the NPCQLQ-C (child age in years mean = 8.61; S.D. = 4.22). Twenty parents/carers completed the NPCQLQ-A (adult age in years = 33.4, S.D. = 12.2). The sample comprised of 18 males; 20 females with NPC. One child’s and 4 adult’s gender were not reported. Mean proxy-rated NPC severity rating was 4.26 (S.D. 2.89) for children and for 4.45 (S.D. 2.23) for adults.

Item reduction and reliability of the NPCQLQ-C—QoL scale for children

Floor and ceiling effects were checked and no items were removed. Inter-item correlations revealed nine items highly correlated with each other; 5 of these were removed. Removal decisions were made in line with the results of the cognitive interviews; participants felt that some items were too similar, for example: “My child looks forward to new experiences in the future” and “My child is excited by the prospect of taking part in special occasions”; for other items, some felt that they were not relevant, such as “My child feels at peace with themselves”.

Item-total correlations were run and eight items were removed because they did not correlate with the total score (correlations of 0.1 or 0.2) or because they had a negative item-total correlation. Upon reflection, these items could be interpreted differently by each participant, thus did not provide a direct relationship between a high score measuring high QoL. Cronbach’s α of the remaining 15 items was 0.925. A full list of items is reported in Table 5. These items were summed and correlated with the item asking respondents to rate the severity of NPC in the child they were caring for. A higher severity rating significantly correlated with poorer QoL with a large effect size (r = − 0.094).

Item reduction and reliability of the NPCQLA-A—QoL scale for adults

Floor and ceiling effects were checked and no items were removed. Inter-item correlations revealed nine items highly correlated with each other and 5 of these were removed. Items were removed based on results from the cognitive interviews. Participants felt that some items were too similar, for example: “They feel content in day to day life” and “On the whole they feel content”; for other items, some felt that they were not relevant, for example: “In general, they feel that their physical state does not allow them to do the things they want to do.”

Item-total correlations were run on the remaining 33 items. Three items were removed because they did not correlate with the total score (correlations of 0.1 or 0.2) or they had a negative item-total correlation. Again upon reflection these items could be interpreted differently by each participant, therefore did not provide a direct relationship between high score and high QoL. Cronbach’s α of the remaining 30 items was 0.947, indicating excellent internal consistency. A full list of items is in Table 6. These items were summed and correlated with the item asking respondents to rate the severity of NPC in the person they were caring for. A higher severity rating significantly correlated with poorer QoL with a large effect size (r = − 0.080).

Discussion

Adopting a phenomenological approach to explore the experiences of living with illness allowed for a richer understanding of how QoL is impacted upon when living with NPC. Using the elements of the lifeworld enriched our understanding of participants’ subjective experiences which then ensured the items included in the scale represented participants’ worlds when living with NPC. The initial reliability tests demonstrate the excellent internal consistency of the items in the scales for children and adults living with NPC. This information could be used to direct healthcare to more appropriate areas and to provide information for patients, parents/carers and healthcare practitioners on the effectiveness of drug treatments and other health-related interventions for those living with NPC.

The NPCQLQ-C items focused on the embodied experience of living with NPC, both in terms of the ‘objective’, physical manifestation of NPC, and the subjective, in terms of children’s contentment with being in their body. Prognosis varies but people who display neurological symptoms in childhood have been shown to deteriorate faster compared to those who become symptomatic later on in life [27]. Items around whether children could play with their toys or whether NPC had affected their embodiment were shown to be important to a child’s QoL in that they could no longer take part in activities they could previously and the frustration this may arouse.

The NPCQLQ-A items focused more on the intersubjective sense of self and how this related to the temporal element of the life they once knew before their diagnosis with NPC, compared to the life they are now living. Many of the adults diagnosed with NPC had to leave employment and their social relationships had changed. For many, a change in identity was felt, and this led to spells of anxiety and depression due to the life they felt they had lost. Although many of the adults had better physical health than children with NPC, the impact on QoL could be greater, highlighting the complexity of the effects of this life-limiting condition on a person’s QoL and how this is not necessarily directly associated with the physical/objective body. Without explicitly exploring each element of the lifeworld, these nuances in people’s experiences may not have been identified.

Furthermore, drawing on the lifeworld theory means that both measures, the NPCQLQ-C and NPCQLQ-A are theoretically underpinned by an existential-phenomenological theory which transcends the individual. This also means that we have been able to go beyond concepts of QoL used in more ‘traditional’ measures. The intention of such a design is to prioritise the concerns of the individuals involved by first exploring the nature of their experience and moreover, to examine the meanings those people attribute to their experiences. This is especially valuable when working with such a rare condition because it then means that these meaningful experiences, rather than preconceived notions from other QoL scales, are used as the starting point for a measurement that can then be used in clinical practice and research.

Using this method may help people who are answering the questionnaire to be reflective, which in turn allows for concrete experiences to come to the fore rather than relying on what might be construed as more abstract concepts of QoL. This too aids healthcare professionals and researchers in understanding more about the lifeworld of their patients and the impact of living with NPC on their everyday lives. At the heart of this lifeworld-led approach is a commitment to humanising healthcare, i.e. ensuring that we treat the whole person rather than simply the condition. This study has highlighted the significance of how living with NPC may affect the patient’s sense of self and bodily identity rather than purely focusing on the physiological impact. These scales could be used as a guide in advancing healthcare and policies to better engage with the illness experience in a way that humanises care [28]. This approach has aimed to be sensitive to what really matters to people living with NPC. The next part of the process will be to assess the validity of both the NPCQLQ-C and NPCQLQ-A in a comparative analysis with other validated QoL scales.

Implications for practice

It is important for healthcare professionals to have a more in-depth understanding of the impact of living with NPC on a patient’s QoL. Understanding patients’ and families’ experiences of living with NPC is an under-researched area which could be revolutionary in shaping healthcare professionals’ approaches to treatment for NPC and the impact of those treatments on a person’s QoL. Both the NPCQLQ-C and the NPCQLQ-A provide a robust ‘measurement’ or representation of the more subjective, experiential impact of NPC on an individual’s QoL. Working in a way that prioritises subjective experience and offers a more humanising approach to care would enable services to deliver support that focuses on meaningful person-centred care.

Limitations

A key concern for this work is the small numbers of participants that completed the QoL questionnaires. However, with such a rare condition this is not surprising. For both the NPCQLQ-C and the NPCQLQ-A, nearly 50% of the diagnosed population in the UK completed a questionnaire, which proportionally offers a good representation of the diagnosed population. In addition, condition-specific scales have been criticised for their narrowness in focus, because they neglect to measure more general outcome variables [29]. However, it is important, especially in rare diseases, to understand the issues that are specific to people living with that condition and very little is known about NPC in this respect. Condition-specific scales measuring QoL are more useful in detecting changes in a condition over time compared to a generic scale [30]. This allows for the domains of QoL that are important to the population in question to be described and quantified [19].

Conclusion

The NPCQLQ-C and the NPCQLQ-A were developed to capture the experiential, real life impact of NPC on patients’ daily lives for the purposes of both clinical practice and research. For example, they may be used in the assessment of QoL during the development, evaluation and implementation of new treatments and other interventions in clinical trials. These are the first disease-specific tools to measure QoL in this population and will enable healthcare professionals and researchers to have a better understanding of the impact of living with this rare disease on a patient’s daily life. The initial reliability analysis of both scales shows excellent internal consistency and they are highly correlated with disease severity, which suggests there is good reason to test and evaluate their use in clinical practice. We argue that using the scales would give voice to patients and would promote more dialogue between patients, parents/carers and healthcare professionals that is grounded in lived experience thereby delivering meaningful person-centred care.

References

Patterson, M. C., Hendriksz, C. J., Walterfang, M., Sedel, F., Vanier, M. T., Wijburg, F., et al. (2012). Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Niemann-Pick disease type C: An update. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism, 106, 330–344.

Patterson, M. C., Mengel, E., Wijburg, F. A., Muller, A., Schwierin, B., Drevon, H., et al. (2013). Disease and patient characteristics in NP-C patients: Findings from an international disease registry. Orphanet Journal of Rare Disease, 8, 73.

Joachim, G., & Acorn, S. (2003). Life with a rare chronic disease: The scleroderma experience. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 42, 598–606.

Bury, M. (1982). Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociology of Health & Illness, 4, 167–182.

Reeve, J., Lloyd-Williams, M., Payne, S., & Dowrick, C. (2010). Revisiting biographical disruption: Exploring individual embodied illness experience in people with terminal cancer. Health, 14, 178–195.

Carel, H. (2007). Can I be ill and happy? Philosophia, 35, 95–110.

Charmaz, K. (1983). Loss of self: A fundamental form of suffering in the chronically Ill. Sociology of Health & Illness, 5, 168–195.

Moch, S. D. (1989). Health within illness: Conceptual evolution and practical possibilities. Advances in Nursing Science, 11(4), 23–31.

Kassianos, A. P. (2016). Quality of life research. In S. E. Boslaugh (Ed.), SAGE encyclopedia of pharmacology and society (4th ed.). California: Sage Publications Inc.

WHOQOL Group. (1995). The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Social Science and Medicine, 41(10), 1403–1409.

WHOQOL Group (1997). WHOQOL Measuring Quality of Life. Division of mental health and prevention of substance abuse: World Health Organization. Retrieved April 28, from http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/68.pdf.

Todres, L., Galvin, K., & Dahlbery, K. (2007). Lifeworld-led healthcare: Revisiting a humanising philosophy that integrates emerging trends. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 10, 53–63.

Husserl, E. (1970). The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology: An introduction to phenomenological philosophy. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and time. Oxford: Blackwell.

Ashworth, P. (2006). Seeing oneself as a carer in the activity of caring: Attending to the lifeworld of a person with Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 1, 212–225.

Dowling, M. (2007). From Husserl to van Manen. A review of different phenomenological approaches. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 44(1), 131–142.

Todres, L., & Galvin, K. (2010). “Dwelling-mobility”: An existential theory of well-being. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 5, 5444.

Bunge, M. (1975). What is a quality of life indicator? Social Indicators Research, 2, 65–79.

Davis, E., Mackinnon, A., Davern, M., Boyd, R., Bohanna, I., Waters, E., et al. (2013). Description and psychometric properties of the CP QoL-teen: A quality of life questionnaire for adolescents with cerebral palsy. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34, 344–352.

Pesudov, K., Burr, J. M., Harley, C., & Elliott, C. B. (2007). The development, assessment and selection of questionnaires. Optometry Vision Science, 84, 603–674.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Centre for Drug Evaluation and Research (2009). Guidance for industry: Patient-reported outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labelling claims. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf.

Todres, L., & Galvin, K. (2006). Caring for a partner with alzheimer’s disease: Intimacy, loss and the life that is possible. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 1, 50–61.

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. London: Sage.

Koch, T. (1996). Implementation of a hermeneutic inquiry in nursing: Philosophy, rigor and representation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 24, 174–184.

Carlozzi, N. E., Schilling, S., Kratz, A. L., Paulsen, J. S., Frank, S., & Stout, J. C. (2018). Understanding patient-reported outcome measures in huntington disease: At what point is cognitive impairment related to poor measurement reliability? Quality of Life Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1912-6.

Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53–55.

Vanier, M. T. (2015). Complex lipid trafficking in niemann-pick disease type c. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease, 38, 187–199.

Galvin, K. T., Sloan, C., Cowdell, F., Ellis-Hill, C., Pound, C., Watson, R., et al. (2018). Facilitating a dedicated focus on the human dimensions of care in practice settings: Development of a new humanised care assessment tool (HCAT) to sensitive care. Nursing Inquiry. https://doi.org/10.1111/nin.12235.

Bowling, A. (2001). Measuring Disease. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Bjornson, K. F., & McLaughlin, J. F. (2001). The measurement of health-related quality of life (hrqol) in children with cerebral palsy. European Journal of Neurology, 8, 183–193.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd for funding the study, all parent/carers and patients for taking part and the NPUK charity for their support in helping with recruitment.

Funding

This study was funded by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd. The company had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report or the decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualisation of the study; LA recruited participants and collected the data; LA led the analyses, all authors contributed to the qualitative analysis and RK contributed to the statistical analyses; LA led on writing the paper with contributions from RK and RS.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

RCK has received a research grant and speaker honorarium from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd. LA has received PhD fees, a bursary and funding to attend conferences from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd. RS declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Aston, L., Shaw, R. & Knibb, R. Preliminary development of proxy-rated quality-of-life scales for children and adults with Niemann-Pick type C. Qual Life Res 28, 3083–3092 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02234-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02234-5