Abstract

Purpose

Only few prospective studies have been conducted on the contribution of quality of life-related factors to the risk of cancer. The aim of this study was to investigate the prospective associations of three quality of life-related factors with the risk of cancer; life satisfaction, vitality, and self-rated health.

Methods

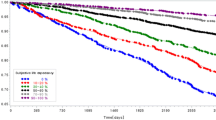

In 2009–2011, 7189 participants in the Copenhagen Aging and Midlife Biobank were asked to rate their life satisfaction, their vitality, and their health. The study population was followed until the end of 2015 for registration of cancer in the Danish National Patient Register.

Results

During the follow-up period, cancer was diagnosed in 312 individuals. Life satisfaction was not associated with the risk of cancer. Vitality was significantly associated with the risk of cancer, but the association became non-significant after adjustment for age, sex, socioeconomic position, and lifestyle factors. However, when additionally adjusting for life satisfaction, individuals who rated their vitality as low had a hazard ratio of 1.46 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.04–2.07) for the development of cancer. Individuals who rated their health as poor had a hazard ratio of 1.70 (95% CI 1.27–2.26) for the development of cancer, compared with individuals with good, very good, or excellent self-rated health. The association remained significant after adjustment for basic confounders, life satisfaction, and vitality.

Conclusion

A better grasp of the significance of quality of life-related factors for the risk of cancer may be of great importance to population-based cancer prevention that aims to target early risk factors for development of cancer across widespread cancer sites.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Garssen, B. (2004). Psychological factors and cancer development: Evidence after 30 years of research. Clinical Psychology Review, 24(3), 315–338.

Dalton, S. O., et al. (2002). Mind and cancer. do psychological factors cause cancer? European Journal of Cancer, 38(10), 1313–1323.

Chiriac, V. F., Baban, A., & Dumitrascu, D. L. (2018). Psychological stress and breast cancer incidence: A systematic review. Clujul Medical, 91(1), 18–26.

Santos, M. C. L., et al. (2009). Association between stress and breast cancer in women: A meta-analysis. Cadernos de Saude Publica, 25, S453–S463.

Edelman, S. (2005). Relationship between psychological factors and cancer: An update of the evidence. Clinical Psychologist, 9(2), 45–53.

Duijts, S. F., Zeegers, M., & Borne, B. V. (2003). The association between stressful life events and breast cancer risk: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Cancer, 107(6), 1023–1029.

Nielsen, N. R., & Gronbaek, M. (2006). Stress and breast cancer: A systematic update on the current knowledge. Nature Clinical Practice Oncology, 3(11), 612–620.

Chida, Y., et al. (2008). Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nature Clinical Practice Oncology, 5(8), 466–475.

Coyne, J. C., Ranchor, A. V., & Palmer, S. C. Meta-analysis of stress-related factors in cancer. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 2010. 7(5).

Lemogne, C., et al. (2013). Depression and the risk of cancer: A 15-year follow-up study of the GAZEL cohort. American Journal of Epidemiology, 178(12), 1712–1720.

Hamer, M., Chida, Y., & Molloy, G. J. (2009). Psychological distress and cancer mortality. Journal Psychosomatic Research, 66(3), 255–258.

Bergelt, C., et al. (2005). Vital exhaustion and risk for cancer: A prospective cohort study on the association between depressive feelings, fatigue, and risk of cancer. Cancer, 104(6), 1288–1295.

Flensborg-Madsen, T., et al. (2011). A prospective association between quality of life and risk for cancer. European Journal of Cancer, 47(16), 2446–2452.

Roelsgaard, I. K., et al. (2016). Self-rated health and cancer risk—A prospective cohort study among Danish women. Acta Oncology, 55(9–10), 1204–1209.

Benyamini, Y. (2011). Why does self-rated health predict mortality? An update on current knowledge and a research agenda for psychologists. Milton Park: Taylor & Francis.

Latham, K., & Peek, C. W. (2013). Self-rated health and morbidity onset among late midlife U.S. adults. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Science, 68(1), 107–116.

Pijls, L. T., Feskens, E. J., & Kromhout, D. (1993). Self-rated health, mortality, and chronic diseases in elderly men. The Zutphen Study, 1985–1990. The American Journal of Epidemiology, 138(10), 840–848.

Riise, H. K., et al. (2014). Poor self-rated health associated with an increased risk of subsequent development of lung cancer. Quality of Life Research, 23(1), 145–153.

Topp, C. W., et al. (2015). The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84(3), 167–176.

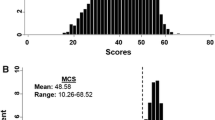

Ware, J. E. Jr., & Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30(6), 473–483.

Bjorner, J. B., et al. (1998). Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability of the Danish SF-36. The Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(11), 1001–1011.

Lins, L., & Carvalho, F. M. (2016). SF-36 total score as a single measure of health-related quality of life: Scoping review. SAGE Open Medicine, 4, 2050312116671725.

Maynard, S., et al. (2015). Associations of subjective vitality with DNA damage, cardiovascular risk factors and physical performance. Acta Physiologica, 213(1), 156–170.

Bjorner, J. B., et al. (2007). Interpreting score differences in the SF-36 Vitality scale: Using clinical conditions and functional outcomes to define the minimally important difference. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 23(4), 731–739.

Shirom, A. (2011). Vigor as a positive affect at work: Conceptualizing vigor, its relations with related constructs, and its antecedents and consequences. Review of General Psychology, 15(1), 50.

Shirom, A., et al. (2010). Vigor, anxiety, and depressive symptoms as predictors of changes in fibrinogen and C-reactive protein. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 2(3), 251–271.

Shirom, A., et al. (2013). Burnout and vigor as predictors of the incidence of hyperlipidemia among healthy employees. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 5(1), 79–98.

Osler, M., et al. (2006). Cohort profile: The Metropolit 1953 Danish male birth cohort. International Journal of Epidemiology, 35(3), 541–545.

Christensen, U., et al. (2004). Cynical hostility, socioeconomic position, health behaviors, and symptom load: A cross-sectional analysis in a Danish population-based study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 66(4), 572–577.

Zachau-Christiansen, B., & Ross, E. M. (1975). Babies: Human development during the first year. New York: John Wiley.

Lund, R., et al. (2016). Cohort profile: The copenhagen aging and midlife biobank (CAMB). International Journal of Epidemiology, 45(4), 1044–1053.

Diener, E., et al. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

Pavot, W., et al. (1991). Further validation of the Satisfaction with Life Scale: Evidence for the cross-method convergence of well-being measures. Journal of Personality Assessment, 57(1), 149–161.

Neuberger, G. B. (2003). Measures of fatigue: The fatigue questionnaire, fatigue severity scale, multidimensional assessment of fatigue scale, and short form-36 vitality (energy/fatigue) subscale of the short form health survey. Arthritis Care & Research: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology, 49(S5), S175–S183.

Bech, P., et al. (2003). Measuring well-being rather than the absence of distress symptoms: A comparison of the SF-36 Mental Health subscale and the WHO-Five well-being scale. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 12(2), 85–91.

Bjorner, J. B., et al. (1998). The Danish SF-36 Health Survey: Translation and preliminary validity studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(11), 991–999.

Idler, E. L., & Benyamini, Y. (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 21–37.

Jurgensen, H. J., et al. (1986). Registration of diagnoses in the Danish National Registry of Patients. Methods of Information in Medicine, 25(3), 158–164.

Pedersen, C. B. (2011). The Danish civil registration system. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 39(7_suppl), 22–25.

Benyamini, Y., et al. (2011). Changes over time from baseline poor self-rated health: For whom does poor self-rated health not predict mortality? Psychology & Health, 26(11), 1446–1462.

Potischman, N., Troisi, R., & Vatten, L. (2004). A life course approach to cancer epidemiology. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology (pp. 260–280). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

van der Linden, B. W., et al., Effect of childhood socioeconomic conditions on cancer onset in later life: An ambidirectional cohort study. International Journal of Public Health, 2018: p. 1–12.

Lynge, E., Madsen, M., & Engholm, G. (1989). Effect of organized screening on incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in Denmark. Cancer Research, 49(8), 2157–2160.

Olsen, A. H., et al. (2005). Breast cancer mortality in Copenhagen after introduction of mammography screening: Cohort study. BMJ, 330(7485), 220.

Kronborg, O., et al. (1996). Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. The Lancet, 348(9040), 1467–1471.

Ruthig, J. C., et al. (2011). Later life health optimism, pessimism and realism: Psychosocial contributors and health correlates. Psychology & Health, 26(7), 835–853.

Ruthig, J. C., Chipperfield, J. G., & Payne, B. J. (2011). A five-year study of older adults’ health incongruence: Consistency, functional changes and subsequent survival. Psychology & Health, 26(11), 1463–1478.

Prior, K. N., & Bond, M. J. (2010). New dimensions of abnormal illness behaviour derived from the illness behaviour questionnaire. Psychology and Health, 25(10), 1209–1227.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank (A) L. Villumsen and (B) Zachau-Christiansen for their role in the establishment of the Copenhagen Perinatal Cohort and the steering committee for permission to conduct this study. Furthermore, we thank Kirsten Avlund, Helle Bruunsgaard, Nils-Erik Fiehn, Åse Marie Hansen, Poul Holm-Pedersen, Rikke Lund, Erik Lykke Mortensen and Merete Osler, who initiated and established the Copenhagen Aging and Midlife Biobank (CAMB). We also thank the staff at the Department of Public Health, University of Copenhagen, and the staff at the National Research Centre for the Working Environment, who undertook the CAMB data collection.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from IMK Almene Fond to Trine Flensborg-Madsen. The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The article has not been submitted elsewhere or published previously and the authors have no relationships that might lead to conflicts of interest. All authors have read the final version of the manuscript; they meet the requirements for authorship and believe that the manuscript represents honest work.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Folker, A.P., Hegelund, E.R., Mortensen, E.L. et al. The association between life satisfaction, vitality, self-rated health, and risk of cancer. Qual Life Res 28, 947–954 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-2083-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-2083-1