Abstract

Background

Patients are participating more actively in health care decision-making with regard to their health, as well as in the broader realm of assessing the value of medical products and influencing decisions about their registration and reimbursement. There is an increasing trend to include patients’ perspectives throughout the stages of medical product development by broadening the traditional study-participant role to that of an active partner throughout the process. Including patients in the selection and development of clinical outcome assessments (COAs) to evaluate the benefit of treatment is particularly important. Still, despite widespread enthusiasm, there is substantial uncertainty regarding how and when to engage patients in this process.

Purpose

This manuscript proposes a methodological framework for engaging patients at varying levels in the selection and development of COAs for medical product development.

Framework

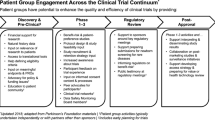

The framework builds on the Food and Drug Administration’s roadmap for patient-focused COA. Methods for engaging patients across each stage in this roadmap are summarized by levels of engagement. Opportunities and examples of patient engagement (PE) in the selection and/or development of COAs are summarized, together with best practices and practical considerations.

Conclusion

This paper offers a framework for understanding, planning, and implementing methods to advance PE in the selection and/or development of COAs for evaluating the benefit of medical products. The intent is to further this important discussion and enhance the process and outcome of PE in this context.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Walton, M. K., Powers, J. H., Hobart, J., Patrick, D., Marquis, P., Vamvakas, S., et al. (2015). Clinical outcome assessments: conceptual foundation-report of the ispor clinical outcomes assessment—emerging good practices for outcomes research task force. Value Health, 18(6), 741–752. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2015.08.006.

Food and Drug Administration (2015). Clinical outcome assessment (COA): Glossary of terms. Retrieved November 21, 2016 from http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DrugDevelopmentToolsQualificationProgram/ucm370262.htm.

Food Drug Administration (FDA). (2009). Guidance for industry patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Federal Register, 74(235), 65132–65133.

Carman, K. L., Dardess, P., Maurer, M., Sofaer, S., Adams, K., Bechtel, C., et al. (2013). Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Affairs (Millwood), 32(2), 223–231. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133.

Boutin, M., Dewulf, L., Hoos, A., & et al. (2016). Culture and Process Change as a Priority for Patient Engagement in Medicines Development. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science.

Patient Focused Medicines Development (2016). patientfocusedmedicines.org. Available at: patientfocusedmedicnes.org. Accessed November 21 2016.

Hanna, M. L., Oehrlein, E. M., Perfetto, E. M., Astratinei, V., Berner, T., Burke, L. B., et al. (2016). Attributes Definiting Patient Engagement and Centeredness in Health Care Research and Practice: A Framework Developed by the ISPOR Patient-Centered Special Interest Group. Paper presented at the ISPOR 19th Annual European Congress, Vienna, Austria, October 29-November 2, 2016.

National Health Council/Genetic Alliance (2015). Dialogue/advancing meaningful patient engagement in research, development, and review of drugs.

Merriam-Webster (2016). Simple definition: Caregiver. Retrieved November 3, 2016 from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/caregiver.

Food and Drug Administration (2015). Drug development tools (DDT) qualification programs. Retrieved November 4, 2016 from http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DrugDevelopmentToolsQualificationProgram/.

The Digital Health Corner (2012). How patient-centric care differs from patient-centered care. Retrieved November 21 2016 from https://davidleescher.com/2012/03/03/how-patient-centric-care-differs-from-patient-centered-care-2/.

Concannon, T. W., Meissner, P., Grunbaum, J. A., McElwee, N., Guise, J. M., Santa, J., et al. (2012). A new taxonomy for stakeholder engagement in patient-centered outcomes research. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(8), 985–991. doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2037-1.

eyeforpharma Patient-Centric Profitability: Pharma’s global survey & analysis. A discussion of results from The Aurora Project:19.

Association of Clinical Research Professionals (2016). Patient-centric approach helps cut costs and speed clinical Trials, Sanofi exec reports. Retrieved November 4, 2016 from https://www.acrpnet.org/2016/07/14/patient-centric-approach-helps-cut-costs-and-speed-clinical-trials-sanofi-exec-reports/.

Miseta, E. (2015). Buidling a culture of patient centricity at Sanofi. Retrieved November 4, 2016 from http://www.clinicalleader.com/doc/building-a-culture-of-patient-centricity-at-sanofi-0001.

McCallister, E. (2015). Takeda’s patients: How Takeda is integrating the patient perspective into drug development. Retrieved November 4, 2016 from http://www.biocentury.com/biotech-pharma-news/products/2015-01-26/how-takeda-is-integrating-the-patient-perspective-into-drug-development-a01.

RESolutions, L. B. (2016). Genentech’s patient-centric approach to clinical trials. Retrieved November 4, 2016 from http://www.janssen.com/emea/sites/www_janssen_com_emea/files/2792_07jan16_pccultures_whitepaper_v13.pdf.

eyeforpharma (2016). Patient-Centred Culture by Design: Embedding patient-centred focus into the culture of pharmaceutical organisations. Retrieved November 4, 2016 from http://www.janssen.com/emea/sites/www_janssen_com_emea/files/2792_07jan16_pccultures_whitepaper_v13.pdf.

Davies, N. (2016). A structural and cultural transformation for a patient-focused UCB. Retrieved November 4 2016 from http://social.eyeforpharma.com/commercial/structural-and-cultural-transformation-patient-focused-ucb.

Friends of Cancer Research (2014). 12-24-2014—Life Science Leader—Pfizer: Putting the patient at the center of its drug development universe. Retrieved November 4, 2016 from http://www.focr.org/12-24-2014-life-science-leader-pfizer-putting-patient-center-its-drug-development-universe.

Yarbrough, C. (2015). Patient-focused drug development: To understand patients, you must engage them. Retrieved November 4, 2016 from http://www.lifescienceleader.com/doc/patient-focused-drug-development-to-understand-patients-you-must-engage-them-0001.

PatientsLikeMe (2015). PatientsLikeMe and AstraZeneca announce global research collaboration. Retrieved November 4, 2016 fromhttp://blog.patientslikeme.com/2015/04/13/patientslikeme-and-astrazeneca-announce-global-research-collaboration/.

Accenture Consulting (2016). The patient is IN: Pharma’s growing opportunity in patient services. Key findings from a survey of 200+ patient services executives in the pharmaceutical industry. Retrieved November 4, 2016 from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DrugDevelopmentToolsQualificationProgram/UCM370174.pdf.

Government of Canada (2014). (Archived) Minister ambrose announces patient involvement pilot for orphan drugs. Retrieved November 4, 2016 from http://news.gc.ca/web/article-en.do?nid=873619.

Domecq, J. P., Prutsky, G., Elraiyah, T., Wang, Z., Nabhan, M., Shippee, N., et al. (2014). Patient engagement in research: A systematic review. BMC Health Service Research, 14, 89. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-14-89.

Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative (CTTI) (2015). CTTI recommendations: Effective engagement with patient groups around clinical trials. Retrieved November 21, 2016 from http://www.ctti-clinicaltrials.org/files/PatientGroups/PGCTrecs.pdf.

Frank, L., Forsythe, L., Ellis, L., Schrandt, S., Sheridan, S., Gerson, J., et al. (2015). Conceptual and practical foundations of patient engagement in research at the patient-centered outcomes research institute. Quality of Life Research, 24(5), 1033–1041. doi:10.1007/s11136-014-0893-3.

toddbernermd.com (2016). Collaborative Patient Engagement: Mapping the Global Landscape. A first step in co-creaqting an action-orentated framework for patient engagement. Retrieved November 21, 2016 from http://toddbernermd.com/wp-content/uploads/ToddBernerMD-com/sites/1376/PFMD-white-paper_FINAL-3.pdf.

Food and Drug Administration (2016). Roadmap to patient-focused outcome measurement in clinical trials. Retrieved November 4, 2016 from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DrugDevelopmentToolsQualificationProgram/UCM370174.pdf.

Cook, K. F., Kallen, M. A., Victorson, D., & Miller, D. (2015). How much change really matters? Development and comparison of two novel approaches to defining clinically important differences in fatigue scores. Quality of Life Research, 24(Suppl 1), 157–158.

Gelhorn, H. L., Kulke, M. H., O’Dorisio, T., Yang, Q. M., Jackson, J., Jackson, S., et al. (2016). Patient-reported symptom experiences in patients with carcinoid syndrome after participation in a study of telotristat etiprate: A qualitative interview approach. Clinical Therapeutics, 38(4), 759–768. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.03.002.

Papadopoulos, E. (2016). Establishing evidence of treatment benefit: focus on outcome assessment. Retrieved November 21, 2016 from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/OncologicDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM375588.pdf.

Thissen, D., Liu, Y., Magnus, B., Quinn, H., Gipson, D. S., Dampier, C., et al. (2016). Estimating minimally important difference (MID) in PROMIS pediatric measures using the scale-judgment method. Quality of Life Research, 25(1), 13–23. doi:10.1007/s11136-015-1058-8.

Voqui, J. (2015). Clinical outcome assessment implementation in clinical trials. Retrieved November 21, 2016 from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/SmallBusinessAssistance/UCM466471.pdf.

European Patients’ Academy on Therapeutic Innovation (2016). Patient advocates involved in clinical development. Retrieved March 16, 2017 from www.eupati.eu/clinical-development-and-trials/patient-advocates-involved-in-clinical-development/.

PatientsLikeMe (2016). patientslikeme.com. Retrieved November 21, 2016 from www.patientslikeme.com.

Smart Patients (2016). Smart patients: An online communicty where patients and caregivers can learn from each other. Retrieved November 21, 2016 from https://www.smartpatients.com/.

McCarrier, K. P., Bull, S., Fleming, S., Simacek, K., Wicks, P., Cella, D., et al. (2016). Concept elicitation within patient-powered research networks: A feasibility study in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Value Health, 19(1), 42–52. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2015.10.013.

Mannix, S., Skalicky, A., Buse, D. C., Desai, P., Sapra, S., Ortmeier, B., et al. (2016). Measuring the impact of migraine for evaluating outcomes of preventive treatments for migraine headaches. Health and Quality Life Outcomes, 14(1), 143. doi:10.1186/s12955-016-0542-3.

Hareendran, A., Setyawan, J., Pokrzywinski, R., Steenrod, A., Madhoo, M., & Erder, M. H. (2015). Evaluating functional outcomes in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: development and initial testing of a self-report instrument. Health and Quality Life Outcomes, 13, 133. doi:10.1186/s12955-015-0302-9.

de Wit, M. P., Kvien, T. K., & Gossec, L. (2015). Patient participation as an integral part of patient-reported outcomes development ensures the representation of the patient voice: a case study from the field of rheumatology. RMD Open, 1(1), e000129. doi:10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000129.

Food and Drug Administration (2015). Advisory Committes: Membership types. Retrieved November 21, 2016 from http://www.fda.gov/AdvisoryCommittees/AboutAdvisoryCommittees/CommitteeMembership/MembershipTypes/default.htm.

Beyond Ceilac (2015). How beyond celiac is forcing the pathways to a cure: Amplifying your voices. Accellerating research. Retrieved November 21, 2016 from http://www.beyondceliac.org/researchsummit/.

Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation (2016). Pulmonary fibrosis foundation interstitial lung disease patient diagnostic journey (INTENSITY) Survey Fact Sheet. Retrieved November 21, 2016 from http://www.multivu.com/players/English/7684251-pulmonary-fibrosis-foundation-patient-survey/docs/intensity-survey-fact-sheet-1025796344.pdf.

Merkel, P. A., Manion, M., Gopal-Srivastava, R., Groft, S., Jinnah, H. A., Robertson, D., et al. (2016). The partnership of patient advocacy groups and clinical investigators in the rare diseases clinical research network. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 11(1), 66. doi:10.1186/s13023-016-0445-8.

Food and Drug Administration (2015). Duchenne muscular dystrophy and related dystrophinopathies: Developing drugs for treatment. Guidance for industry. Draft guidance. Retrieved November 4, 2016 from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM450229.pdf.

Myotonic Dystrophy Foundation (2015). MDF workshop examines clinical trial endpoints and biomarkers. Retrieved November 21, 2016 from http://www.myotonic.org/mdf-workshop-examines-clinical-trial-endpoints-and-biomarkers.

Food and Drug Administration Qualification of biomarker plasma fibrinogen in studies examining exacerbations and/or all-cause mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Guidance for industry. Retrieved November 4, 2016 from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM453496.pdf.

Seattle Quality of Life Group (2016). Cystic fibrosis respiratory symptom diary (CFRSD) and chronic respiratory infection symptom score (CRISS©). Retrieved November 2016 from http://depts.washington.edu/seaqol/CFRSD-CRISS.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (2014). Strategy for patient-oriented research—patient engagement framework. Retrieved November 21, 2016 from http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48413.html.

Lowe, M. M., Blaser, D. A., Cone, L., Arcona, S., Ko, J., Sasane, R., et al. (2016). Increasing patient involvement in drug development. Value Health, 19(6), 869–878. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2016.04.009.

National Health Society (2016). Principles to patient and public engagement. Retrieved November 21, 2016 from http://www.newdevonccg.nhs.uk/get-involved/get-involved/principles-to-patient-and-public-engagement/100506.

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (2016). Engagement rubric for applicants. Retrieved November 21, 2016 from http://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/Engagement-Rubric.pdf.

Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative (2015). Guiding principles for patient engagement: Nusing experts release guiding principles for patient enagagement. Retrieved November 21, 2016 from https://www.pcpcc.org/resource/guiding-principles-patient-engagement.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2014). Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. AHRQ Publication No. 10(14)-EHC063-EF. Rockville, MD.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2016). What is the effective health care program. https://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/index.cfm/what-is-the-effective-health-care-program1/.

Food and Drug Administration (2016). About the FDA Patient Representative Program. Retrieved October 24, 2016 from http://www.fda.gov/ForPatients/About/ucm412709.htm.

Food and Drug Administration (2016). For patients. Retrieved October 24, 2016 from http://www.fda.gov/ForPatients/.

Food and Drug Administration (2016). Section 1137: Patient participation in medical product discussions. Retrieved October 24, 2016 from http://www.fda.gov/ForPatients/PatientEngagement/ucm483931.htm.

Food and Drug Administration. (2012). Prescription Drug User Fee Act V patient-focused drug development; public meeting and request for comment. Federal Register, 77, 58848–58849.

Food and Drug Administration (2016). Patient preference initiative. Retrieved October 23, 2016 from http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CDRH/CDRHPatientEngagement/ucm462830.htm.

Food and Drug Administration (2015). Patient Engagement Advisory Committee. Retrieved October 24, 2016 from http://www.fda.gov/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/PatientEngagementAdvisoryCommittee/ucm20081796.htm.

Food and Drug Administration (2016). Coming soon: New patient engagement initiative. Retrieved October 24, 2016 from http://www.fda.gov/ForPatients/PatientEngagement/ucm506248.htm.

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (2016). Changing the conversation about health research. Retrieved October 24, 2016 from http://www.pcori.org.

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (2015). Become a PCORI Ambassador. Retrieved October 24, 2016 from http://www.pcori.org/content/become-pcori-ambassador.

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (2016). Patient-powered research networks. Retrieved November 21, 2016 from http://pcornet.org/patient-powered-research-networks/.

European Medicines Agency (2016). Patients’ and consumers’ working party. Retrieved October 24, 2016 from http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/partners_and_networks/general/general_content_000708.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac05809e2d8c.

European Medicines Agency (2010). Benefit-risk methodology project. Work package 2 report: Applicability of current tools and processes for regulatory benefit-risk assessment. Retrieved October 24, 2016 from http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2010/10/WC500097750.pdf.

European Medicines Agency (2015). European Medicines Agency’s interaction with patients, consumers, healthcare professionals and their organisations. Annual report 2014. Retrieved October 24, 2016 from http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2015/10/WC500195083.pdf.

Innovative Medicines Initiative (2016). The innovative medicines initiative. Retrieved November 4, 2016 from https://www.imi.europa.eu/.

Pravettoni, G. (2016). PREFER—patient preferences in benefit-risk assessments during the drug life cycle. Retrieved October 23, 2016 from http://www.gabriellapravettoni.com/en/imi-prefer-patients-preferences-in-benefit-risk-assessments-during-the-drug-life-cycle/.

European Patients Forum (2016). website. Retrieved November 21, 2016 from http://www.eu-patient.eu/.

European Patients’ Academy on Therapeutic Innovation (2016). What is EUPATI? Retrieved November 4, 2016 from https://www.eupati.eu/what-is-eupati/.

National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (1999). Patient and public involvement policy. Retrieved November 20, 2016 from https://www.nice.org.uk/about/nice-communities/public-involvement/patient-and-public-involvement-policy.

Acknowledgements

H. Wilson, M. Anatchkova, A. Hareendran, K. Coyne, C. McHorney, and N.K. Leidy are employed by Evidera, a health care research firm that provides outcome consulting and other research services to pharmaceutical, device, government, and non-government organizations. K. Wyrwich was employed by Evidera at the time the manuscript was developed, but is now currently employed by Eli Lilly and Company. E. Dashiell-Aje was employed by Evidera during the time the manuscript was developed, but is now currently employed at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This publication reflects the views of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views, policies, or guidance of the FDA. This paper does not represent any new FDA guidance or policy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Research involving human and animal participants

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wilson, H., Dashiell-Aje, E., Anatchkova, M. et al. Beyond study participants: a framework for engaging patients in the selection or development of clinical outcome assessments for evaluating the benefits of treatment in medical product development. Qual Life Res 27, 5–16 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1577-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1577-6