Abstract

Objective

To test equivalence of scores obtained with the PROMIS® pediatric Depressive Symptoms, Fatigue, and Mobility measures across two modes of administration: computer self-administration and telephone interviewer-administration. If mode effects are found, to estimate the magnitude and direction of the mode effects.

Methods

Respondents from an internet survey panel completed the child self-report and parent proxy-report versions of the PROMIS® pediatric Depressive Symptoms, Fatigue, and Mobility measures using both computer self-administration and telephone interviewer-administration in a crossed counterbalanced design. Pearson correlations and multivariate analysis of variance were used to examine the effects of mode of administration as well as order and form effects.

Results

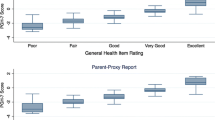

Correlations between scores obtained with the two modes of administration were high. Scores were generally comparable across modes of administration, but there were some small significant effects involving mode of administration; significant differences in scores between the two modes ranged from 1.24 to 4.36 points.

Conclusions

Scores for these pediatric PROMIS measures are generally comparable across modes of administration. Studies planning to use multiple modes (e.g., self-administration and interviewer-administration) should exercise good study design principles to minimize possible confounding effects from mixed modes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- PROMIS® :

-

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System®

- NIH:

-

National Institutes of Health

- PRO:

-

Patient-reported outcome

- PDA:

-

Personal digital assistant

- MOA:

-

Mode of administration

- MANOVA:

-

Multivariate analysis of variance

- MD:

-

Mahalanobis distance

References

Cella, D., Riley, W., Stone, A., Rothrock, N., Reeve, B., Yount, S., et al. (2010). The patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63(11), 1179–1194. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011.

Bjorner, J. B., Rose, M., Gandek, B., Stone, A. A., Junghaenel, D. U., & Ware, J. E, Jr. (2014). Difference in method of administration did not significantly impact item response: An IRT-based analysis from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) initiative. Quality of Life Research, 23(1), 217–227. doi:10.1007/s11136-013-0451-4.

Bjorner, J. B., Rose, M., Gandek, B., Stone, A. A., Junghaenel, D. U., & Ware, J. E, Jr. (2014). Method of administration of PROMIS scales did not significantly impact score level, reliability, or validity. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(1), 108–113. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.07.016.

Beebe, T. J., McRae, J. A, Jr., Harrison, P. A., Davern, M. E., & Quinlan, K. B. (2005). Mail surveys resulted in more reports of substance use than telephone surveys. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 58(4), 421–424.

Hanmer, J., Hays, R. D., & Fryback, D. G. (2007). Mode of administration is important in US national estimates of health-related quality of life. Medical Care, 45(12), 1171–1179. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181354828.

Powers, J. R., Mishra, G., & Young, A. F. (2005). Differences in mail and telephone responses to self-rated health: Use of multiple imputation in correcting for response bias. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 29(2), 149–154.

McHorney, C. A., Kosinski, M., & Ware, J. E, Jr. (1994). Comparisons of the costs and quality of norms for the SF-36 health survey collected by mail versus telephone interview: Results from a national survey. Medical Care, 32(6), 551–567.

Kraus, L., & Augustin, R. (2001). Measuring alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems: Comparison of responses from self-administered questionnaires and telephone interviews. Addiction, 96(3), 459–471. doi:10.1080/0965214002005428.

Irwin, D. E., Stucky, B., Langer, M. M., Thissen, D., Dewitt, E. M., Lai, J. S., et al. (2010). An item response analysis of the pediatric PROMIS anxiety and depressive symptoms scales. Quality of Life Research, 19(4), 595–607. doi:10.1007/s11136-010-9619-3.

Lai, J. S., Stucky, B. D., Thissen, D., Varni, J. W., Dewitt, E. M., Irwin, D. E., et al. (2013). Development and psychometric properties of the PROMIS® pediatric fatigue item banks. Quality of Life Research. doi:10.1007/s11136-013-0357-1.

Dewitt, E. M., Stucky, B. D., Thissen, D., Irwin, D. E., Langer, M., Varni, J. W., et al. (2011). Construction of the eight-item patient-reported outcomes measurement information system pediatric physical function scales: Built using item response theory. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(7), 794–804. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.012.

Varni, J. W., Thissen, D., Stucky, B. D., Liu, Y., Gorder, H., Irwin, D. E., et al. (2012). PROMIS® parent proxy report scales: An item response theory analysis of the parent proxy report item banks. Quality of Life Research, 21, 1223–1240. doi:10.1007/s11136-011-0025-2.

Cai, L., Thissen, D., & du Toit, S. H. C. (2011). IRTPRO for Windows. Lincolnwood: Scientific Software International.

Robinson-Cimpian, J. P. (2014). Inaccurate estimation of disparities due to mischievous responders: Several suggestions to assess conclusions. Educational Researcher, 43(4), 171–185. doi:10.3102/0013189x14534297.

Bock, R. D. (1975). Multivariate statistical methods in behavioral research. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Schwartz, C. E., Andresen, E. M., Nosek, M. A., Krahn, G. L., & RRTC Expert Panel on Health Status Measurement. (2007). Response shift theory: Important implications for measuring quality of life in people with disability. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 88(4), 529–536. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2006.12.032.

Thissen, D., & Norton, S. (2013). What might changes in psychometric approaches to statewide testing mean for NAEP? In Examining the content and context of the common core state standards: A first look at implications for the National Assessment of Educational Progress (pp. 253–304).

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Maronna, R. A., & Yohai, V. J. (1995). The behavior of the Stahel–Donoho robust multivariate estimator. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 90(429), 330–341.

Acknowledgments

PROMIS® was funded with cooperative agreements from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Common Fund Initiative (Northwestern University, PI: David Cella, Ph.D., U54AR057951, U01AR052177; Northwestern University, PI: Richard C. Gershon, Ph.D., U54AR057943; American Institutes for Research, PI: Susan (San) D. Keller, Ph.D., U54AR057926; State University of New York, Stony Brook, PIs: Joan E. Broderick, Ph.D. and Arthur A. Stone, Ph.D., U01AR057948, U01AR052170; University of Washington, Seattle, PIs: Heidi M. Crane, M.D., MPH, Paul K. Crane, M.D., MPH, and Donald L. Patrick, Ph.D., U01AR057954; University of Washington, Seattle, PI: Dagmar Amtmann, Ph.D., U01AR052171; University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, PI: Harry A. Guess, M.D., Ph.D. (deceased), Darren A. DeWalt, M.D., MPH, U01AR052181; Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, PI: Christopher B. Forrest, M.D., Ph.D., U01AR057956; Stanford University, PI: James F. Fries, M.D., U01AR052158; Boston University, PIs: Alan Jette, PT, Ph.D., Stephen M. Haley, Ph.D. (deceased), and David Scott Tulsky, Ph.D. (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor), U01AR057929; University of California, Los Angeles, PIs: Dinesh Khanna, M.D. (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor) and Brennan Spiegel, M.D., MSHS, U01AR057936; University of Pittsburgh, PI: Paul A. Pilkonis, Ph.D., U01AR052155; Georgetown University, PIs: Carol. M. Moinpour, Ph.D. (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle) and Arnold L. Potosky, Ph.D., U01AR057971; Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, PI: Esi M. Morgan DeWitt, MD, MSCE, U01AR057940; University of Maryland, Baltimore, PI: Lisa M. Shulman, M.D., U01AR057967; and Duke University, PI: Kevin P. Weinfurt, Ph.D., U01AR052186). NIH Science Officers on this project have included Deborah Ader, Ph.D., Vanessa Ameen, M.D. (deceased), Susan Czajkowski, Ph.D., Basil Eldadah, M.D., Ph.D., Lawrence Fine, M.D., DrPH, Lawrence Fox, M.D., Ph.D., Lynne Haverkos, M.D., MPH, Thomas Hilton, Ph.D., Laura Lee Johnson, Ph.D., Michael Kozak, Ph.D., Peter Lyster, Ph.D., Donald Mattison, M.D., Claudia Moy, Ph.D., Louis Quatrano, Ph.D., Bryce Reeve, Ph.D., William Riley, Ph.D., Peter Scheidt, M.D., Ashley Wilder Smith, Ph.D., MPH, Susana Serrate-Sztein, M.D., William Phillip Tonkins, DrPH, Ellen Werner, Ph.D., Tisha Wiley, Ph.D., and James Witter, M.D., Ph.D. The contents of this article use data developed under PROMIS. These contents do not necessarily represent an endorsement by the US Federal Government or PROMIS. See www.nihpromis.org for additional information on the PROMIS® initiative. This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (Grant Number U01AR052181).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Reeve was an unpaid member of the Board of Directors for the PROMIS Health Organization (PHO) during the conduct of this study and preparation of the manuscript. Dr. DeWalt is an author of some of the items in the PROMIS instruments and owns the copyright for these items. Dr. DeWalt has given an unlimited free license for the use of the materials to the PROMIS Health Organization. The remaining authors have no financial relationships or conflicts of interest relevant to this study to disclose.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Research involving human participants

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Magnus, B.E., Liu, Y., He, J. et al. Mode effects between computer self-administration and telephone interviewer-administration of the PROMIS® pediatric measures, self- and proxy report. Qual Life Res 25, 1655–1665 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1221-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1221-2