Abstract

Purpose

No previous study has estimated the association between bullying and preference-based health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (“utility”), knowledge of which may be used for cost-effectiveness studies of interventions designed to prevent bullying. Therefore, the aim of the study was to estimate preference-based HRQoL among victims of bullying compared to non-victims.

Methods

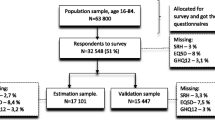

A cross-sectional survey data collection among Swedish adolescents aged 15–17 years in the first year of upper secondary school was conducted in the city of Gothenburg in Sweden (N = 758). Preference-based HRQoL was estimated with the SF-6D. Regression analyses were conducted to adjust for some individual-level background variable.

Results

Mean preference-based health-related quality of life scores were 0.77 and 0.71 for non-victims and victims of bullying, respectively. The difference of 0.06 points was statistically significant (p < 0.05) and robust to inclusion of gender, age, and parental immigrant status.

Conclusions

The preference-based HRQoL estimates in this study may be used as an upper bound in economic evaluations of bullying prevention interventions, facilitating a comparison between costs and quality-adjusted life-years.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hawker, D. S. J., & Boulton, M. J. (2000). Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocia maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41(4), 441–455.

Takizawa, R., Maughan, B., & Arseneault, L. (2014). Adult health outcomes of childhood bullying victimization: Evidence from a five-decade longitudinal British birth cohort. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(7), 777–784.

Frisén, A., & Bjarnelind, S. (2010). Health-related quality of life and bullying in adolescence. Acta Paediatrica, 99(4), 597–603.

Wilkins-Shurmer, A., O’Callaghan, M., Najman, J., Bor, W., Williams, G., & Anderson, M. (2003). Association of bullying with adolescent health-related quality of life. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 39(6), 436–441.

Rigby, K., & Smith, P. K. (2011). Is school bullying really on the rise? Social Psychology of Education, 14(4), 441–455.

Currie, C., Zanotti, C., Morgan, A., Currie, D., de Looze, M., Roberts, C., Samdal, O., Smith, O., & Barnekow, V. (2012). Social determinants of health and well-being among young people : Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) study : International report from the 2009/2010 survey. (No. 9289014237). Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

Sundell, K., & Forster, M. (2005). En grund för att växa i Gränslös utmaning—alkoholpolitik i ny tid [A foundation for growth in Limitless challenge-alcohol policy in the new era] I: Gränslös utmaning [Limitless challange] (SOU 2005:25) (appendix 8). Stockholm.

Flygare, E., Gill, P. E., & Johansson, B. (2013). Lessons from a concurrent evaluation of eight antibullying programs used in Sweden. American Journal of Evaluation, 34(2), 170–189.

Ttofi, M., Farrington, D., & Baldry, A. (2008). Effectiveness of programmes to reduce school bullying—A systematic review. Stockholm: The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention.

SNAE. (2009). Kostnader för förskoleverksamhet, skolbarnsomsorg, skola och vuxenutbildning 2008: Skolverket (The Swedish National Agency for Education).

Gold, M., Siegel, J., Russell, L., & Weinstein, M. (1996). Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

NICE. (2004). Guide to the methods of technology appraisal.

Socialstyrelsen. (2011). Nationella riktlinjer för sjukdomsförebyggande metoder 2011 - Hälsoekonomiskt underlag (Bilaga). Socialstyrelsen, Stockholm, Tillgänglig http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/nationellariktlinjerforsjukdomsforebyggandemetoder/Documents/nr-sjukdomsforebyggande-halsoekonomisktunderlag.pdf.

Pliskin, J. S., Shepard, D. S., & Weinstein, M. C. (1980). Utility functions for life years and health status. Operations Research, 28, 206–224.

Zeckhauser, R. J., & Shepard, D. S. (1976). Where now for saving lives? Law and Contemporary Problems, 40(4), 5–45.

Berg, B. (2012). Sf-6d population norms. Health Economics, 21(12), 1508–1512.

Burström, K., Johannesson, M., & Diderichsen, F. (2001). Swedish population health-related quality of life results using the EQ-5D. Quality of Life Research, 10(7), 621–635.

Ladapo, J. A., Neumann, P. J., Keren, R., & Prosser, L. A. (2007). Valuing children’s health: A comparison of cost-utility analyses for adult and paediatric health interventions in the US. Pharmacoeconomics, 25(10), 817–828.

Prosser, L. A., Hammitt, J. K., & Keren, R. (2007). Measuring health preferences for use in cost-utility and cost-benefit analyses of interventions in children: Theoretical and methodological considerations. Pharmacoeconomics, 25(9), 713–726.

Petrou, S., & Kupek, E. (2009). Estimating preference-based health utilities index mark 3 utility scores for childhood conditions in England and Scotland. Medical Decision Making, 29(3), 291–303.

Ware, J. E., Snow, K. K., Kolinski, M., & Gandeck, B. (1993). SF-36 Health survey manual and interpretation guide. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Centre.

Brazier, J., Roberts, J., & Deverill, M. (2002). The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. Journal of Health Economics, 21(2), 271–292.

Torrance, G. W., Boyle, M. H., & Horwood, S. P. (1982). Application of multi-attribute utility theory to measure social preferences for health states. Operations Research, 30(6), 1043–1069.

Brooks, R. (1996). EuroQol: The current state of play. Health Policy, 37(1), 53–72.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

Olweus, D. (1996). The revised Olweus bully/victim questionnaire. Mimeo HEMIL: University of Bergen.

Rigby, K. (1999). Peer victimisation at school and the health of secondary school students. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 69(1), 95–104.

Basu, A., & Manca, A. (2012). Regression estimators for generic health-related quality of life and quality-adjusted life years. Medical Decision Making, 32(1), 56–69.

Drummond, M. (2001). Introducing economic and quality of life measurements into clinical studies. Annals of Medicine, 33(5), 344–349.

Bowes, L., Joinson, C., Wolke, D., & Lewis, G. (2015). Peer victimisation during adolescence and its impact on depression in early adulthood: Prospective cohort study in the United Kingdom. BMJ, 350, h2469.

Eriksen, T. L. M., Nielsen, H. S., & Simonsen, M. (2014). Bullying in Elementary School. Journal of Human Resources, 49(4), 839–871.

ISPOR. (2013). International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research: Pharmacoeconomic Guidelines around the World. http://www.ispor.org/peguidelines/index.asp.

Owen, L., Morgan, A., Fischer, A., Ellis, S., Hoy, A., & Kelly, M. P. (2012). The cost-effectiveness of public health interventions. Journal of Public Health, 34(1), 37–45.

Lawson, K. D., Kearns, A., Petticrew, M., & Fenwick, E. A. L. (2013). Investing in health: Is social housing value for money? A cost-utility analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 67, 829–834.

NICE. (2012). Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance (third edition). http://publications.nice.org.uk/methods-for-the-development-of-nice-public-health-guidance-third-edition-pmg4/incorporating-health-economics.

Richardson, J., Iezzi, A., & Khan, M. (2015). Why do multi-attribute utility instruments produce different utilities: The relative importance of the descriptive systems, scale and ‘micro-utility’ effects. Quality of Life Research, 24, 2045–2053.

van den Berg, B. (2012). Sf-6d population norms. Health Economics, 21(12), 1508–1512.

Card, N., & Hodges, E. (2008). Peer victimization among schoolchildren: Correlations, causes, consequences, and considerations in assessment and intervention. School Psychology Quarterly, 23(4), 451–461.

Sullivan, P. W., & Ghushchyan, V. (2006). Preference-based EQ-5D index scores for chronic conditions in the United States. Medical Decision Making, 26(4), 410–420.

Conflict of interest

The authors, Linda Beckman, Mikael Svensson, and Ann Frisén, declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beckman, L., Svensson, M. & Frisén, A. Preference-based health-related quality of life among victims of bullying. Qual Life Res 25, 303–309 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1101-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1101-9