Abstract

Background

The ASCOT-Carer is a self-report instrument designed to measure social care-related quality of life (SCRQoL). This article presents the psychometric testing and validation of the ASCOT-Carer four response-level interview (INT4) in a sample of unpaid carers of adults who receive publicly funded social care services in England.

Methods

Unpaid carers were identified through a survey of users of publicly funded social care services in England. Three hundred and eighty-seven carers completed a face-to-face or telephone interview. Data on variables hypothesised to be related to SCRQoL (e.g. characteristics of the carer, cared-for person and care situation) and measures of carer experience, strain, health-related quality of life and overall QoL were collected. Relationships between these variables and overall SCRQoL score were evaluated through correlation, ANOVA and regression analysis to test the construct validity of the scale. Internal reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and feasibility by the number of missing responses.

Results

The construct validity was supported by statistically significant relationships between SCRQoL and scores on instruments of related constructs, as well as with characteristics of the carer and care recipient in univariate and multivariate analyses. A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87 (seven items) indicates that the internal reliability of the instrument is satisfactory and a low number of missing responses (<1 %) indicates a high level of acceptance.

Conclusion

The results provide evidence to support the construct validity, factor structure, internal reliability and feasibility of the ASCOT-Carer INT4 as an instrument for measuring social care-related quality of life of unpaid carers who care for adults with a variety of long-term conditions, disability or problems related to old age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Informal care is an important source of support for people with long-term conditions across the OECD countries [1]. Alongside state- or privately funded social care, unpaid care by friends and relatives meets the needs of adults with illness, disability or frailty associated with old age by providing support with everyday activities and personal hygiene. The balance between formal and informal care varies by country and is influenced, at least in part, by differences in social care systems [2, 3]. An important policy concern, especially as the projected availability of informal care is expected to decline while demand for social care increases [4, 5], is how to support unpaid carers in their caring role. This is particularly relevant given the evidence that high-intensity caregiving may adversely affect carers’ health and well-being [6–9] even if carers may also report positive aspects of caring for a friend or relative [10].

In this context, policymakers in many European countries are at various stages of engaging with the question of how best to support carers [11, 12]. There are some countries where policy strategy for the support of carers is already relatively well developed: for example, in England, informal carers have been recognised as vital to support the quality of life (QoL) of adults with long-term conditions [13, 14]. Policymakers have identified the priority areas of carers’ health and well-being and their ability to sustain a life alongside caring and to participate in education or employment [13, 15]. Indeed, the Care Act (2014) aims to improve carers’ access to support services, such as support to remain in employment, support groups or information and advice.

With limited resources to support long-term care systems, however, especially in the context of a projected increase in demand for long-term care in Europe [3], an important concern is how to effectively allocate resources within long-term care systems to support both adults with long-term conditions and their unpaid carers. While such decisions are often made with limited evidence, there has been increasing interest in the measurement of the quality of life outcomes of social care; such measures may enable policymakers, providers and practitioners to evaluate the effectiveness, quality and value of policy or specific interventions and to determine the most appropriate allocation of resources [16]. Although there are a range of instruments that measure carers’ health, experience, well-being, stress or burden [17–19], the effect of social care support on quality of life (QoL) may not be appropriately captured by such instruments. Inappropriate measures could lead to the effects of policy or interventions being missed. This highlights the need for an instrument designed to measure the effect of social care support or the ‘social care-related quality of life’ (SCRQoL) of informal carers [16, 20].

The purpose of this paper is to assess the feasibility, factor structure, internal consistency and construct validity of a new measure of carer QoL with specific relevance to social care, the ASCOT-Carer. The ASCOT-Carer measures social care-related quality of life (SCRQoL) across seven domains (see Table 1) and has been developed alongside the preference-weighted ASCOT-INT4 instrument to measure SCRQoL of users of social care services [21–23]. This article builds on the content validation and preliminary psychometric analyses conducted during the development of the carer social care-related quality of life measure [20, 24, 25] to establish the psychometric properties of the four response-level measure.

Methods

Development of the ASCOT-Carer

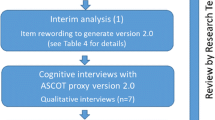

A study conducted in 2007–2008, which drew on two focus groups with care managers and four focus groups with 21 informal carers recruited via carers’ support groups and organisations in Kent, identified seven domains of social care-related quality of life from the carer’s perspective (see Table 1) [25, 26]. The researchers, with support from an advisory group of informal carers and employees of a local authority with adult social care responsibilities, developed a draft questionnaire. The questions were tested in 56 interviews with informal carers using cognitive interviewing methods [27]. This study produced a three response-level version, which is included in the national Personal Social Services Survey of Adult Carers in England (PSS SACE) [28].

The data collected from the 2009/2010 national survey of informal carers known to local authorities in England were analysed to identify the items to include in the final QoL instrument and to establish their psychometric properties [20]. Subsequent cognitive interviewing with 31 carers, which was conducted in 2012 across three local authorities in England, informed minor amendments to the question wording and domain definitions, as well as establishing a four response-level version of the instrument (ASCOT-Carer INT4). This development work is reported in detail elsewhere [29]. The full instrument can be downloaded from the ASCOT website (www.pssru.ac.uk/ascot).

Analysis Sample and Data Collection

A sample of carers was recruited in 22 of the 150 local authorities in England with adult social care responsibilities who were participating in the Identifying the Impact of Adult Social Care (IIASC) study. These local authorities included representatives of all English Government Office regions (with the exception of the East Midlands) and a range of types: shire counties (11); metropolitan districts (6); London Boroughs (3) and unitary authorities (2).

The carers were recruited via adults with physical disabilities or sensory impairment, mental health conditions or intellectual disabilities who were in receipt of fully or partly publicly funded community-based social care support (e.g. home care, day centre, equipment, meals service) and consented to and participated in an interview for the IIASC study. The users of social care services were asked whether anyone helped them with activities of daily living using questions from the Health Survey for England [30]. If the respondent identified that they received help from friends, family or neighbours, then the respondent was asked at the end of the interview to pass on a letter of invitation to their primary informal carer. (Primary informal carer was defined as a friend, neighbour or relative who spent the most number of hours per week helping the person who had participated in the IIASC interview with activities of daily living (ADL) or instrumental ADL (IADL)). The 990 interviews with social care recipients identified 739 informal carers. The respondent agreed to pass an invitation letter to their carer in 510 cases (69.3 %). Of those carers who received an invitation letter, a total of 387 (75.7 %) interviews with eligible carers were completed.

The interviews with carers were conducted between June 2013 and March 2014 using computer-aided personal interviews conducted either face-to-face in people’s homes or by telephone. Written or verbal informed consent was obtained before the interview. Ethical approval was obtained from the social care research ethics committee.

Questionnaire

Social care-related quality of life was measured using the ASCOT-Carer four response-level interview (INT4) [29]. The response options in the ASCOT-Carer INT4 correspond to the carers’ ‘ideal state’ (3), ‘no needs’ (2), ‘low level needs’ (1) and ‘high-level needs’ (0) within each of the seven SCRQoL domains to form an overall score between 0 and 21. Carers were asked to rate each domain of quality of life with respect to their current situation.

Various measures of carer experience, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and quality of life were also included in the interview. The Carer Strain Index (CSI) [31] is a 13-item measure of the strain related to caregiving. The carer is asked to indicate whether (1) or not (0) they have had difficulties with different aspects of caregiving. The Carer Experience Scale (CES) is a preference-weighted measure of caring experience for use in economic evaluations of health and social care interventions [32–34]. The instrument comprises six attributes associated with the experience of caring with three levels of response per attribute. HRQoL was assessed using the EuroQOL-5D (EQ-5D 3L) scored with UK preference values (UK TTO) [35–37]. Overall quality of life was evaluated using a seven-point Likert scale.

The following data were collected from the carer interview: age; sex; employment status; self-reported health; co-residence with the care recipient; and satisfaction with social care support. The suitability of the home for caregiving was assessed using a self-report question with four levels of response developed in earlier work [29]. The UCLA three-item loneliness scale [38] was included as a measure of social isolation. Three items from the Minimum Data Set Cognitive Performance Scale [39] to rate the care recipient’s short-term memory, cognitive skills for daily living and communication, as well as two additional items to capture the care recipient’s disorientation and frequency of behaviours that the carer finds challenging, were also collected. Different aspects of the caregiving situation, such as the duration of caregiving, motivation for providing informal care, number of hours per week of care, the types of care tasks undertaken and the effect of caring on health and employment, were captured using items from the Household Survey of Carers in England 2009/2010 [40]. Socio-demographic data (i.e. age, sex) collected in the care recipient interviews were also linked to the responses to the carer interviews.

Analysis

Analyses were conducted in Stata version 12. The purpose of the analysis is to evaluate the feasibility, factor structure, internal consistency and construct validity of the ASCOT-Carer. Feasibility, or the acceptability of the items to carers, will be evaluated in this study by reviewing the proportion of missing values per item. The internal consistency across the seven items in the ASCOT-Carer is assessed using Cronbach’s alpha [41], which we interpret as an indicator of reliability.

Factor structure

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) conducted in a previous study on a sample of 35,615 informal carers surveyed across 90 councils in England proposed a one-factor (single scale) solution for the seven-item, three-level version of the carer SCRQoL measure [20].Footnote 1 To evaluate whether the seven domains of the four-level instrument measures a single common underlying construct, a one-factor model was applied using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with maximum likelihood estimation. Model fit was assessed using the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the incremental fit statistics (Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) and Comparative Fit Index (CFI)) and the parameter estimates. The model fit cut-off values for acceptability were taken to be a RMSEA of ≤ 0.06 (upper confidence interval of ≤ 0.08), SRMR ≤ 0.08 and CFI/TLI ≥ 0.95 [42].

Construct validity

The construct validity of the instrument to measure carer ‘social care-related quality of life’ is evaluated using regression analysis. Construct validity is based on testing hypotheses of how a measure should behave in relation to other measures or other factors hypothesised to be associated with the measurement construct [43]. The construct validity of the ASCOT-Carer instrument was assessed using convergent validation, which evaluates the extent to which the construct of the ASCOT-Carer measure correlates with different instruments that measure the same or similar constructs [44]. As there are no other instruments that measure carers’ SCRQoL, the convergent validity of the ASCOT-carer was studied by the association between SCRQoL score and instruments that measure the following associated constructs: the subjective effect of caregiving (CSI [31]), health-related quality of life (EQ-5D [35, 36]), the carers’ experience of caregiving (CES) [32–34]) and overall quality of life (single seven-point item). Pearson’s correlation coefficients were used to study the bivariate associations between the ASCOT-Carer score and these instruments.

Another aspect of construct validity describes the extent to which a measure relates to other variables, such as background characteristics (e.g. age, gender) [45]. This was investigated by studying the relationship between overall ASCOT-Carer SCRQoL scores and characteristics of the carer, the nature of the caring relationship and the care recipient. The hypothesised relationships between SCRQoL and other variables are outlined in Table 2. Associations were initially explored using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Multivariate associations were then analysed with ordinary least squares (OLSs) of the ASCOT-Carer score and the characteristics of the carer, the care recipient and the care situation. Respondents with missing values for the dependent or any of the independent variables were excluded (n = 20).

Results

The characteristics of the study sample are summarised in Table 3. There was a majority of females (58.9 %), which is slightly lower than the estimate that 60 % of informal carers in England are women [40]. Only 26.4 % of the samples were in paid employment, which is lower than the estimated national figure (46 %) [40]. The sample profile of employment may be partly linked to the high proportion of carers retired from paid employment (46.2 %) compared with only 27 % of carers in England [40]. In the sample, 60.1 % of carers provided 35 or more hours of care per week. This is comparable to those carers known to local authorities in England, but is higher than the national estimate (30 %) [40]. Although there are differences between the study sample and the population estimate of carers in England, the study sample is comparable to the profile of carers in England known to local authorities [40], which represent the carers who are most likely to access social care services or be in need of support or interventions.

The responses by ASCOT-Carer domain are shown in Table 4. The majority of carers (93.2 %) reported quality of life at the ‘ideal state’ in one or more domain. The rating of each domain at the ideal state ranges from 20.7 % (Space and time to be yourself, feeling encouraged and supported) to 72.1 % (Personal safety). Almost half (49.1 %) of carers had some or high needs in the Occupation domain, whereas only 6.5 % reported that they felt less than adequately safe or not at all safe in the Personal safety domain.

The overall ASCOT-Carer SCRQoL score has a negatively skewed and possibly bi-modal distribution (Fig. 1). The distribution indicates that there may be a ceiling effect at the upper end of the scale. The rate of missing values was low with less than 1 % (3) of respondents who had one or more missing values. This indicates that the questions are acceptable and feasible. Cronbach’s alpha for the ASCOT-Carer SCRQoL score was 0.87 (seven items). An alpha of 0.8–0.9 considered to be good [46], which indicates that the instrument has good internal consistency.

Factor Structure

The results of the confirmatory factor analysis are shown in Table 5, which shows that the overall goodness of fit Chi-square was significant for the hypothesised one-factor model (Model 1, Fig. 2). This suggests a lack of fit between the hypothesised model and the data. Other fit indices were also assessed due to the sensitivity of Chi-square in larger samples (≥200) [47]. These fit indices indicate adequate model fit following the standardised root mean squared residual (SRMR) and the CFI/TLI criteria of ≤0.08 and ≥0.95, respectively. However, the ≤0.06 criterion for the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was not met and the modification indicated that freeing the covariance between the two error terms for Self-care and Personal safety would improve the model fit. Two alternative models to either omit the safety domain (Model 2) or free the path between Self-care and Personal safety (Model 3) were found to have better fit than the constrained model (see Table 5). Model 3 was preferred over Model 2 because of the face validity of the Personal safety domain and the significant improvement in model fit. All items loaded significantly at the 1 % level onto the single factor (ranging from 0.44 to 0.84, see Fig. 3). Change in Chi-square between the constrained (1) and non-constrained model (3) was significant (Δχ 2(1) = 33.6, p < 0.001).

Construct Validity

Associations between ASCOT-Carer score and other related measures are shown in Table 6. As expected, the ASCOT-Carer score was significantly positively associated with EQ-5D and CES (preference weighted), as well as rating of quality of life on a single seven-item scale. There was a significant negative relationship between ASCOT-Carer and the CSI score. These relationships are congruent with the hypothesis that higher social care-related quality of life would be associated with more positive experiences of caregiving, better HRQoL and overall QoL, and lower reported carer strain.

Univariate analysis of the characteristics hypothesised to be associated with ASCOT-Carer score (Table 2) are shown in Table 3. All hypothesised associations, with Bonferroni correction to account for multiple comparisons, reached significance except for carers’ age, duration of caregiving and survey administration mode (p ≥ 0.05). Multivariate regression analysis (Table 7)Footnote 2 shows that, after controlling for other variables included in the model, 12 of the 25 hypothesised relationships reached significance at the 5 % level with one further relationship that indicated a trend towards significance (p < 0.1).

Positive relationships were observed for rating that caregiving had no effect on the carer’s health and for male (compared with female) carers. Negative associations were found for: poor health of carer; poor health of care recipient; higher self-reported social isolation and loneliness; carer and care recipient living together; frequent challenging behaviour by the care recipient; carer motivation for caregiving is that the care recipient would not want anyone else to look after him/her; more than 10 h of informal care undertaken per week; and completion of the interview by telephone compared with face-to-face. There are also negative associations with other reported negative impacts of caring, such as financial difficulties, caregiving affected employment and having less time for social or leisure activities. Finally, as would be expected since the ASCOT-Carer is designed to measure aspects of QoL targeted by social care support, a fair or poor rating of satisfaction with services was significantly related to lower QoL. The largest effects on the ASCOT-Carer score were observed for loneliness and isolation (β = −0.26), the effect of caring on social or leisure activities (β = −0.16), satisfaction with social care services (β = −0.15) and the effect of caring on health (β = −0.14), all of which relate either to aspects of caregiving that social care services may target (e.g. providing information and advice; support to enable carers to socialise or leave the home) or to the perceived quality and adequacy of services.

Discussion

This study shows that the ASCOT-Carer is a unidimensional measure of the social care-related quality of life of unpaid carers of adults with physical disability, sensory impairment, mental health problems and intellectual disabilities in a valid and reliable way. The ASCOT-Carer has excellent feasibility with a very low percentage of non-response to the questions. The ASCOT-Carer INT4 has good internal consistency of responses, which indicates that it has high internal reliability. The factor analysis provides support for the findings of earlier work [20] by indicating that the seven items capture a single underlying factor of social care-related quality of life with covariance of error terms between Self-care and Personal safety domains. The path between these two domains may be justified by the conceptual link between the two constructs. Specifically, they both relate to sense of personal security, safety and care that may be at risk in particular types of caregiving situation: for example, high-intensity dementia caregiving. The covariance of error terms may, however, alternatively be due to a sequential ordering effect since Personal safety directly follows Self-care in the questionnaire, or associated with the marked ceiling effect in the Personal safety domain with 72 % of responses rated at the ideal state. Given the perceived need to retain the Personal safety domain for face validity, however, further work to explore these two domains would be justified.

The analysis presented in this article supports previous qualitative work on the domains of SCRQoL for carers [26, 29] to provide evidence of the construct validity of the ASCOT-Carer. The construct validity analysis demonstrates the expected relationships between ASCOT-Carer score and measures that capture related constructs. The weakest associations are observed between ASCOT-Carer score and the EQ-5D index and five individual EQ-5D dimensions. This would be expected since the EQ-5D captures the distinct (but related) construct of HRQoL, whereas SCRQoL deliberately omits overtly health-related domains to focus instead on other domains associated with the effect of social care on quality of life [21]. Moderate associations were observed for overall quality of life and the carer-specific measures of experience and burden. The ASCOT-Carer performs as expected, and the findings indicate that the measure captures a different construct to existing measures of carer strain, caring experience and health-related quality of life. Furthermore, the hypothesised relationships between SCRQoL and related measures or contextual factors reached significance in the univariate analysis in all except for two cases, and half of these relationships were also significant in multivariate analysis that controls for the other factors. In the multivariate analysis, the largest effects were observed for the perceived quality and adequacy of social care support, as well as factors (e.g. loneliness and isolation, impact of caring on health and social or leisure time) that social care services and policy aim to address. This indicates that the ASCOT-Carer measures what it is intended to measure, namely the aspects of quality of life related to concerns of carers that may be supported by social care service or policy interventions [26].

The ASCOT-Carer parallels the ASCOT for users of social care services, which is a preference-weighted measure of social care-related quality of life designed to be used in effectiveness and cost-effectiveness evaluations of social care policy and practice [21–23]. The ASCOT and ASCOT-Carer have three overlapping domains that are of concern to both social care service users with long-term conditions and their unpaid carers (i.e. Occupation, Social participation and Control over daily life). Although the ASCOT and ASCOT-Carer have been developed based on the distinct concerns of users and carers, they both measure social care-related quality of life and may therefore be used in conjunction with providing an estimate of SCRQoL for an individual and their carer(s). Further work to establish preference weights for the ASCOT-Carer and to map how the two preference-weighted measures complement each other may support the combined use of these two measures in evaluation of the wider impact of policy and practice on both people with long-term conditions and their carers.

The strength of this study is the wide range of variables included in the data set to capture characteristics of the carer, the care recipient and the caregiving situation, which has enabled a comprehensive evaluation of construct validity. Although three hypothesised relationships were not observed, in general the findings support the use of the ASCOT-Carer to measure social care-related quality of life in a diverse group of carers. Nevertheless, the study has some limitations to be highlighted. First, the study presented here does not directly assess the responsiveness of the measure to changes in social care services. This could be addressed by testing for a positive relationship between ASCOT-Carer score and intensity of service use, while controlling for amount of caregiving as a proxy for social care need. Due to incomplete data provided by local authorities, the data set analysed in this article does not include a robust measure of the intensity of social care service support for the carer and/or care recipient. Further work to establish the responsiveness of the ASCOT-Carer to social care interventions, as well as the sensitivity of the instrument to change over time, would, therefore, be valuable. Second, the small number of respondents restricted analyses to the whole sample rather than subgroup analyses that may have been of interest. For example, carers of people with dementia or an analysis of older (≥65 years) compared with younger carers may be instructive given their different needs. Third, the findings indicate that there may be a weak bias towards lower reporting of ASCOT-Carer SCRQoL when data collection is by telephone rather than face-to-face interview. This effect should be considered in future work that draws on a mix of survey administration modes. Finally, this study has only explored reliability in terms of the internal consistency of the measure. Further work to establish the test–retest reliability of the measure is warranted.

Conclusion

This study has provided evidence for the unidimensional factor structure of the ASCOT-Carer INT4 scale and internal consistency of responses. It has also provided good evidence for the construct validity of the measure for a diverse group of carers. These findings are encouraging and support the use of ASCOT-Carer INT4 to measure the outcomes for carers of social care interventions and policy. Further work is required to explore the relationship between the Personal safety and Self-care domains and to explore the properties of the measure for subgroups of carers, for example carers of people with dementia.

Notes

An exploratory factor analysis conducted on the sample presented in this article also proposed a one-factor (single scale) solution for the seven-item, four response-level version. An appendix outlining this analysis is available upon request to the corresponding author.

The residuals are normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk W test for normality (W = 0.996 V = 0.971 Z = −0.070 p = 0.528). The variance of the residuals is homogenous (White’s test for heteroskedasticity (χ²(326) = 339.8, p = 0.288). There is no evidence for omitted variable bias (Ramsey-reset test for omitted variables (F(3,338) = 0.76, p = 0.517).

References

OECD. (2011). Informal carers. In Health at a glance 2011: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health_glance-2011-en.

Kraus, M., Riedel, M., Mot, E., Willemé, P., Röhrling, P., & Czypionka, T. (2010). A typology of long-term care in Europe. ENEPRI Research Report No. 91.

Pickard, L. (2011). The supply of informal care in Europe. ENEPRI Research Report No. 94.

Colombo, F., Llena-Nozal, A., Mercier, J., & Tjadens, F. (2011). Help wanted? Providing and paying for long-term care. Paris: OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264097759-en.

Pickard, L., & King, D. (2012). Informal care supply and demand in Europe. ENEPRI Research Report No 116.

Schulz, R., & Beach, S. (1999). Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality. The caregiver health effects study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 282(23), 2215–2219.

Schulz, R., Newsom, J., Mittelmark, M., Burton, L., Hirsch, C., & Jackson, S. (1997). Health effects of caregiving: The caregiver health effects study: An ancillary study of the cardiovascular health study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 19, 110–116.

Sorensen, S., Duberstein, P., Gill, D., & Pinquart, M. (2006). Dementia care: Mental health effects, intervention strategies, and clinical implications. Lancet Neurology, 5(11), 961–973.

Bridges, S. (2013). Health Survey for England 2012 Chapter 5. Well-being. London: NatCen, University College London.

Cohen, C., Colantonio, A., & Vernich, L. (2002). Positive aspects of caregiving: Rounding out the caregiver experience. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17(2), 184–188.

Naiditch, M. (2012). Protecting an endangered resource? Lessons from a European cross-country comparison of support policies for informal carers of elderly dependent persons. Questions d’Economie de la Sante, 176, 1–8.

Courtin, E., Jemiai, N., & Mossialos, E. (2014). Mapping support policies for informal carers across the European Union. Health Policy, 118, 84–94.

Department of Health. (2010). Recognised, valued and supported: Next steps for the carers strategy. London: Department of Health.

Department of Health. (2012). Caring for our future: Reforming care and support. London: HM Government.

Department of Health. (2014). Carers strategy: Second national action plan 2014–2016. London: Department of Health.

Netten, A. (2011). Overview of outcome measurement for adults using social care services and support. National Institute for Health Research, School for Social Care Research.

Hudson, P. L., Trauer, T., Graham, S., Grande, G., Ewing, G., Payne, S., et al. (2010). A systematic review of instruments related to family caregivers of palliative care patients. Palliative Medicine, 24(7), 656–668.

Harvey, K., Catty, J., Langman, A., Winfield, H., Clement, S., Burns, E., et al. (2008). A review of instruments developed to measure outcomes for carers of people with mental health problems. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 117(3), 164–176.

Moniz-Cook, E., Vernooij-Dassen, M., Woods, R., Verhey, F., Chattat, R., De Vugt, M., et al. (2008). A European consensus on outcome measures for psychosocial intervention research in dementia care. Aging and Mental Health, 12(1), 14–29.

Malley, J., Fox, D., & Netten, A. (2010). Developing a carers’ experience performance indicator. Canterbury: Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent.

Netten, A. P., Burge, P., Malley, J., Potoglou, D., Towers, A., Brazier, B., et al. (2012). Outcomes of social care for adults: Developing a preference-weighted measure. Health Technology Assessment, 16(16), 1–166.

Malley, J., Towers A-M, Netten, A., Brazier, J., Forder, J., & Flynn T. (2012). An assessment of the construct validity of the ASCOT measure of social care-related quality of life with older people. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 10(21). http://www.hqlo.com/content/10/1/21.

Potoglou, D., Burge, P., Flynn, T., Netten, A., Malley, J., Forder, J., & Brazier, J. (2011). Best-worst scaling vs discrete choice experiments: An empirical comparison using social care. Social Science and Medicine, 72(10), 1717–1727.

Smith, N., Fox, D., & Holder, J. (2009). Developing and using the 2009/10 Carers’ Survey, SSRG Conference, ‘User experience surveys: Today and tomorrow’. Birmingham.

Smith, N., & Holder, J. (2008). Measuring outcomes for carers. In British Society of Gerontology Annual Conference.

Holder, J., Smith, N., & Netten, A. (2009). Outcomes and quality for social care services for carers: Kent County Council carers survey development project 2007–2008. Technical report Canterbury: Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent.

Willis, G. (2005). Cognitive interviewing: A tool for improving questionnaire design. London: Sage.

Fox, D., Holder, J., & Netten, A. (2010). Personal social services of adult carers in England 2009–10: Survey development project—Technical Report. Canterbury: Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent.

Rand, S., Malley, J., & Netten, A. (2012). Identifying the impact of adult social care (IIASC): Interim technical report. Canterbury: Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent.

Blake, M., Gray, M., Balarajan, M., Darton, R., Hancock, R., Henderson, C., King, D., Malley, J., Pickard, L., & Wittenberg, R. (2010). Social Care for older people aged 65+, questionnaire documentation. NatCen, PSSRU LSE, PSSRU University of Kent and the University of East Anglia.

Robinson, B. (1983). Validation of a caregiver strain index. Journal of Gerontology, 38, 344–348.

Al-Janabi, H., Coast, J., & Flynn, T. N. (2008). What do people value when they provide unpaid care? A meta-ethnography with interview follow-up. Social Science and Medicine, 67, 111–121.

Al-Janabi, H., Flynn, T. N., & Coast, J. (2011). Estimation of a preference-based carer experience scale. Medical Decision Making, 31(3), 458–468.

Goranitis, I., Coast, J., & Al-Janabi, H. (2014). An investigation into the construct validity of the Carer Experience Scale (CES). Quality of Life Research, 23(6), 1743–1752.

Brooks, R. (1996). EuroQol: The current state of play. Health Policy, 37(1), 53–72.

The EuroQol Group. (1990). EuroQol-a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy, 16(3), 199–208.

Kind, P., Hardman, G., & Macran, S. (1999). UK population norms for EQ-5D. York Centre for Health Economics, Discussion Paper, University of York.

Hughes, M., Waite, L., Hawkley, L., & Cacioppo, J. (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys. Research on Aging, 26, 655–672.

Morris, J. N., Fries, B. E., Mehr, D. R., Hawes, C., Phillips, C., Mohr, V., & Lipsitz, L. A. (1994). MDS cognitive performance scale©. Journal of Gerontology, 49(4), M174–M182.

Department of Health. (2010). Survey of carers in households 2009/10. London: Department of Health.

Cronbach, L. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297–334.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55.

Cronbach, L., & Meehl, P. E. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin, 52, 281–302.

Hays, R. D., Anderson, R., & Revicki, D. (1993). Psychometric considerations in evaluating health-related quality of life measures. Quality of Life Research, 2, 441–449.

Streiner, D. L., & Norman, G. R. (2003). Health measurement scales: A practical guide to their development and use. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cortina, J. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(1), 98–104.

Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

Greenwood, N., Mackenzie, A., Cloud, G. C., & Wilson, N. (2008). Informal carers of stroke survivors—Factors influencing carers: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Disability and Rehabilitation, 30(18), 1329–1349.

Schoenmakers, B., Buntinx, F., & Delepeleire, J. (2010). Factors determining the impact of care-giving on caregivers of elderly patients with dementia. A systematic literature review. Maturitas, 66(2), 191–200.

Molloy, G. J., Johnston, D. W., & Witham, M. D. (2005). Family caregiving and congestive heart failure. Review and analysis. European Journal of Heart Failure, 7(4), 592–603.

Harden, J. (2005). Developmental life stage and couples’ experiences with prostate cancer: A review of the literature. Cancer Nursing, 28(2), 85–98.

White, C. L., Mayo, N., Hanley, J. A., & Wood-Dauphinee, S. (2003). Evolution of the caregiving experience in the initial two years following stroke. Research in Nursing & Health, 26, 177–189.

Van den Heuvel, E. T. P., de Witte, L. P., Schure, L. M., Sanderman, R., & Meyboom-de Jong, B. (2001). Risk factors for burnout in caregivers of stroke patients, and possibilities for intervention. Clinical Rehabilitation, 15, 669–677.

Morley, D., Dummett, S., Peters, M., Kelly, L., Hewitson, P., Dawson, J., Fitzpatrick, R., & Jenkinson, C. (2012). Factors influencing quality of life in caregivers of people with Parkinson’s disease and implications for clinical guidelines. Parkinson’s Disease, 2012, 6. doi:10.1155/2012/190901.

Kitrungrote, L., & Cohen, M. Z. (2006). Quality of life of family caregivers of patients with cancer: A literature review. Oncology Nursing Forum, 33(3), 625–632.

Ekwall, A. K., Sivberg, B., & Hallberg, I. R. (2005). Loneliness as a predictor of quality of life among older caregivers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(1), 23–32.

McKeown, L. P., Porter-Armstrong, A. P., & Baxter, G. D. (2003). The needs and experiences of caregivers of individuals with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Clinical Rehabilitation, 17(3), 234–248.

Zegwaard, M. I., Aartsen, M. J., Cuijpers, P., & Grypdonck, M. H. (2011). Review: A conceptual model of perceived burden of informal caregivers for older persons with a severe functional psychiatric syndrome and concomitant problematic behaviour. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20(15–16), 2233–2258.

Mockford, C., Jenkinson, C., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2006). A review: Carers, MND and service provision. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, 7(3), 132–141.

Stenberg, U., Ruland, C. M., & Miaskowski, C. (2010). Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 19(10), 1013–1025.

Quinn, C., Clare, L., & Woods, R. T. (2010). The impact of motivations and meanings on the wellbeing of caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 22(1), 43–55.

Quinn, C., Clare, L., McGuinness, T., & Woods, R. T. (2012). The impact of relationships, motivations, and meanings on dementia caregiving outcomes. International Psychogeriatrics, 24(11), 1816–1826.

Camden, A., Livingston, G., & Cooper, C. (2011). Reasons why family members become carers and the outcome for the person with dementia: Results from the CARD study. International Psychogeriatrics, 23(9), 1442–1450.

Romero-Moreno, R., Marquez-Gonzalez, M., Losada, A., & Lopez, P. (2011). Motives for caring: Relationship to stress and coping dimensions. International Psychogeriatrics, 23(4), 573–582.

Gaugler, J. E. (2010). The longitudinal ramifications of stroke caregiving: A systematic review. Rehabilitation Psychology, 55(2), 108–125.

Reed, S. I. (2008). First-episode psychosis: A literature review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 17(2), 85–91.

Bowling, A. (2005). Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. Journal of Public Health, 27(3), 281–291.

De Leeuw, E. D., & van der Zouwen, J. (1988). Data quality in telephone and face-to-face surveys: A comparative meta-analysis. In R. M. Groves, P. P. Biemer, L. E. Lyberg, J. T. Massey, W. L. Nichols II, & J. Waksberg (Eds.), Telephone survey methodology (pp. 283–299). New York: Wiley.

Evans, M., Kessler, D., Lewis, G., Peters, T. J., & Sharp, D. (2004). Assessing mental health in primary care using standardized scales: Can it be carried out over the telephone? Psychological Medicine, 34, 157–162.

Acknowledgments

The research on which this article is based was funded by the Department of Health and undertaken by researchers at the Quality and Outcomes of Person-Centred Care Research Unit (QORU). The views expressed here are those of the authors and are not necessarily shared by any individual, government department of agency. We are very grateful to all who participated in the research and to Accent, who undertook the fieldwork. We are also grateful to Jacquetta Holder, Diane Fox and Nick Smith who undertook much of the development work for this measure.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rand, S.E., Malley, J.N., Netten, A.P. et al. Factor structure and construct validity of the Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit for Carers (ASCOT-Carer). Qual Life Res 24, 2601–2614 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1011-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1011-x