Abstract

Purpose

“Healthy days” are calculated by adding the number of poor physical and mental health days and subtracting the total from 30 days using the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) scale. This study sought to compute the index with forced responses and hypothesized significant HRQOL differences with demographic and risk behavior variables would be observed.

Methods

Using the 1997 South Carolina YRBS and a 2007 university data set, variables were created based on the averages within each response option from the index items (e.g., 1–2 days would assigned as 1.5 days, etc.). Then the greater of the two values in each respective cell (poor physical or mental health days) was chosen for the analysis.

Results

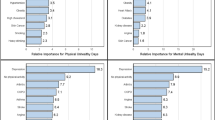

Although some differences existed between the two samples, the same general pattern of responses was established. Significant HRQOL differences were observed among selected demographic, substance use, weight perception, and self-rated health variables (P < .05).

Conclusions

Preliminary evidence suggests the “healthy days” calculation is a valid approach with fixed option responses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- HRQOL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- YRBS:

-

Youth risk behavior survey

- GHDs:

-

Good health days

- PPHDs:

-

Poor physical health days

- PMHDs:

-

Poor mental health days

- BRFSS:

-

Behavioral risk factor surveillance system

- HP 2010:

-

Healthy people 2010

References

Department of Health and Human Services. (2009). Healthy people 2010: Understanding and improving health. http://web.health.gov/healthypeople. Accessed July, 21, 2009.

Ballis, D. S., Segall, A., & Chipperfield, J. G. (2003). Two views of self-rated general health status. Social Science and Medicine, 56(2), 203–217.

Benjamins, M. R., Hummer, R. A., Eberstein, I. W., et al. (2004). Self reported health and adult mortality risk. Social Science and Medicine, 59(6), 1297–1306.

Farkas, J., Nabb, S., Zaletel-Kragelj, L., et al. (2009). Self-rated health and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. European Journal of Heart Failure, 11(5), 518–524.

Idler, E. L., & Benyamini, Y. (1997). Self-rated health and mortality. A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38(1), 21–37.

Segovia, J., Bartlett, R. F., & Edwards, A. C. (1989). The association between self-assessed health status and individual health practices. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 80, 32–37.

Centers for Disease Control. (1994). Quality of life as a new public health measure-behavior risk factor surveillance system MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 43(20), 375–380.

Centers for Disease Control. (1995). Health-related quality of life measures-United States, 1993 MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 44(11), 195–200.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2000). Measuring Healthy Days. Atlanta, Georgia: CDC.

Hennessy, C. A., Moriarty, D. G., Zack, M. M., et al. (1994). Measuring health-related quality of life for public health surveillance. Public Health Reports, 109(5), 665–672.

Issued by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Newschaffer, C. J. (1998). Validation of the BRFSS HRQOL measures in a statewide sample. Final report. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; Prevention Centers Grant No. U48/CCU710806-01.

Ware, J. E., & Sherbourne, D. C. (1992). The MOS 36-item short form health survey (SF-36): Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30(6), 473–483.

Andresen, E. M., Fouts, B. S., Romeis, J. C., et al. (1999). Performance of health-related quality-of-life instruments in a spinal cord injury population. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 80, 877–884.

Diwan, S., & Moriarty, D. (1994). A conceptual framework for identifying unmet health care needs of community dwelling elderly. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 14(1), 47–63.

Nanda, U., & Andresen, E. M. (1998). Performance measures of health-related quality of life and function among disabled adults [abstract]. Quality of Life Research, 7, 644.

Zullig, K. J., Valois, R. F., Huebner, E. S., et al. (2004). Evaluating the performance of the Centers for Disease Control’s core health-related quality of life scale among adolescents. Public Health Reports, 119(6), 577–584.

Zullig, K. J. (2005). Using the centers for disease control and prevention’s core health-related quality of life scale on a college campus. American Journal of Health Behavior, 29(6), 569–578.

Andresen, E. M., Catlin, T. K., Wyrich, K. W., et al. (2003). Retest reliability of surveillance questions on health related quality of life. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57, 339–343.

Kapp, J., Jackson-Thompson, J., Petroski, G., et al. (2009). Reliability of health-related quality-of-life indicators in cancer survivors from a population-based sample, 2005, BRFSS. Public Health, 123(4), 321–325.

Brener, N. D., Collins, J. L., Kann, L., et al. (1995). Reliability of the youth risk behavior survey questionnaire. American Journal of Epidemiology, 141(6), 575–580.

Brener, N. D., Kann, L., McManus, T., et al. (2002). Reliability of the 1999 youth risk behavior survey questionnaire. Journal of Adolescent Health, 31(4), 336–342.

Kolbe, L. J. (1990). An epidemiological surveillance system to monitor the prevalence of youth behaviors that most affect health. Journal of Health Education, 21(6), 44–48.

Pealer, L. N., Weiler, R. M., Pigg, R. M., et al. (2001). The feasibility of a web-based surveillance system to collect risk behavior data from college students. Health Education & Behavior, 28(5), 547–559.

Fowler, F. (1992). Survey research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. (Applied Social Research Methods Series; Vol. 1, 2nd ed.).

Rosenbaum, J. E. (2009). Truth or consequences: The intertemporal consistency of adolescent self-report on the Youth Risk Behavior Survey. American Journal of Epidemiology, 169(11), 1388–1397.

Tourangeau, R. (1999). Remembering what happened: memory errors and survey reports. In A. A. Stone, J. S. Turkkan, C. A. Bachrach, et al. (Eds.), Science of Self-report: Implications for research and practice (pp. 29–48). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Vida, R., Brownlie, E. B., Beitchman, J. H., et al. (2009). Emerging adult outcomes of adolescent psychiatric and substance use disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 34(10), 800–805.

Faith, M. A., Malcolm, K. Y., & Newgent, R. A. (2008). Reducing potential mental health issues and alcohol abuse through an early prevention model for victims of peer harassment. Work, 31(3), 327–335.

St John, P. D., Montgomery, P. R., & Tyas, S. L. (2009). Alcohol misuse, gender and depressive symptoms in community dwelling seniors. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24(4), 369–375.

Skarbo, T., Rosenvinge, J. H., & Holte, A. (2006). Alcohol problems, mental disorder and mental health among suicide attempters 5–9 years after treatment by child and adolescent outpatient psychiatry. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 60(5), 351–358.

Goldsmith, A. A., Tran, G. Q., Smith, J. P., et al. (2009). Alcohol expectancies and drinking motives in college drinkers: Mediating effects on the relationship between generalized anxiety and heavy drinking in negative-affect situations. Addictive Behaviors, 34(5), 505–513.

Pate, R. R., Health, G. W., Dowda, M., et al. (1996). Associations between physical activity and other health behaviors in a representative sample of U.S. adolescents. American Journal of Public Health, 86(11), 1577–1581.

Winnail, S. D., Valois, R. F., McKeown, R. E., et al. (1995). Relationship between physical activity level and cigarette, smokeless tobacco, and marijuana use among high school adolescents. Journal of School Health, 65(10), 438–442.

Centers for Disease Control. (1998). State differences in reported healthy days among adults-United States, 1993–1995 MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 47(12), 239–243.

Centers for Disease Control. (1998). Self-Reported Frequent Mental Distress Among Adults-United States, 1993–1996. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 47(16), 325–331.

Sehulster, J. R. (1994). Health and self: Paths for exploring cognitive aspects underlying self-report of health status. In S. Schechter (Ed.) Proceedings of the 1993 NCHS conference on the cognitive aspects of self-reported health status. Working Paper Series, No. 10: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Hyattsville, MD (pp. 89–105).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zullig, K.J. Creating and using the CDC HRQOL healthy days index with fixed option survey responses. Qual Life Res 19, 413–424 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9584-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9584-x