Abstract

In this paper we examine three forms of regret in relation to the UK’s hugely significant referendum on EU membership that was held in June 2016. They are: (i) whether ‘leave’ voters at the referendum subsequently regretted their choice (in the light of the result), (ii) whether non-voters regretted their decisions to abstain (essentially supporting ‘remain’) and (iii) whether individuals were more likely to indicate that it is everyone’s duty to vote following the referendum. We find evidence in favor of all three types of regret. In particular, leave voters and non-voters were significantly more likely to indicate that they would vote to remain given a chance to do so again; moreover, the probability of an individual stating that it was everyone’s duty to vote in a general election increased significantly in 2017 (compared to 2015). The implications of the findings are discussed in the context of the referendum’s outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

This paper contributes to the large and growing literature spawned by the UK’s decision to leave the EU in 2016, or ‘Brexit’. A central focus has been on the characteristics of leave and remain voters and theories as to what caused voters to vote as they did. The outcome of the referendum was perceived by most people as a shock, including many ardent leavers. Most experts argued (and still do) that Brexit will be costly for the citizens of the United Kingdom.Footnote 1 Identifying the characteristics of voters and explaining how they voted clearly has been the main focus of research on the ballot itself (Clarke et al., 2017; Sobolewska & Ford, 2020). A common argument made in some media outlets is that because remain was expected to win, many leave voters registered a protest leave vote and regretted it afterwards.Footnote 2 Using the British Social Attitudes Survey (BSAS), we will study such regret, but also shift focus towards those who did not vote on the referendum. Another common argument made after the referendum was that non-voters could have changed the outcome to remain had they voted.Footnote 3 In particular, frustration frequently was expressed among remain voters concerning younger people not voting in the proportion that older people did, because younger voters predominantly associate with remain and older voters are more associated with leave.Footnote 4

If a very high level of regret is expressed after an election, the natural instinct of many commentators is to see voters’ remorse as a serious cause for concern.Footnote 5 But one might respond that remorse is just the nature of electoral decision-making. A constitutionally accepted process is applied in collective decision-making and sometimes the decisions will be very close and potentially represent sources of regret. We agree that for constitutionally accepted electoral rules it is hard to establish whether regret is a significant problem given that, in a democracy, opportunities to correct mistakes will be available at the next election. However, for a referendum, such as Brexit, aimed at changing the constitution itself, it is recognized explicitly that an opportunity for correction will not arise in any near future. Such a concern with regret in such cases brings into play prominent themes in constitutional political economy stemming back to Buchanan & Tullock (1962). It raises questions as to whether referendums should require supermajorities or whether a second referendum should be held for issues when the eventual outcome is unknown at the time of the first referendum and should be subject to a confirmatory referendum. Those are thorny normative issues that we do not engage herein. Our concern is to test for significant regret after the Brexit referendum. However, the analysis to follow does beg questions regarding the validity of a simple majority rule for major constitutional change. A key difference between a close election and a close referendum, we would argue, is that the first naturally has more legitimacy than the latter. Elections generally are outcomes of commonly accepted constitutional rules and readily offer opportunities for mistake corrections. Referendums aim to change constitutional rules and do not readily offer voters opportunities to remedy mistakes. Therefore, a tight referendum result can appear illegitimate to those on the losing side in a way that a close election defeat (supposing that the relevant rules were known and adhered to) is not viewed as illegitimate by the losers. Hobolt et al., (2022) and Matsusaka (2020, Chap. 12) study the issue of the Brexit referendum and political legitimacy.Footnote 6

For the Brexit referendum, we can see that two types of post referendum regret often are posited. First, that some voters regret voting ‘leave’. That proposition, while widely stated, has been hard to sustain as a source of regret affecting large numbers of leave voters.Footnote 7 While it may be that survey respondents do not wish to acknowledge their regret, we do still find some evidence that leave voters would be more likely than remainers to switch on a new ballot. However, the second form of regret attributed to non-voters can be established more clearly; it comes in two forms, one familiar and one not.

The familiar form of regret is that non-voters would now vote in significant numbers on a new referendum and that a majority of that group of new voters would vote remain. The less familiar form of regret concerns voter motivation. Not surprisingly non-voters were much less likely than voters in the referendum to state duty as a motive for voting. We show that non-voters appear to revise their own attitudes to voting substantially after 2016, with a significant increase in abstainers stating ‘duty’ as a motive for voting. Therefore, an indirect effect of the Brexit referendum is the influence it may have had on attitudes to voting. If Brexit triggered a rising sense of civic duty (especially amongst the young), the revised attitudes could have significant effects on the turnout of future elections and their outcomes. Of course, any change in voting attitudes may be short-lived but it is also possible that Brexit may have been a shock from which the after-effects persist not just economically and politically but also in terms of attitudes to democratic participation that would in turn feed into future politics and economics.

An important question is whether the sources of regret that we identify would be sufficient to overturn the result of 2016. Clearly, data taken from survey results must be treated with caution and a (very unlikely) fresh referendum would, no doubt, trigger passions in a way that cannot be predicted in advance. However, we show that a significant majority surveyed claim that they would vote remain in a new referendum and that, we argue, is driven by leave voters being more likely to switch to remain than vice versa; by non-voters in 2016 being significantly more likely to vote and vote remain and, moreover, that a stronger sense of duty may contribute to higher turnouts amongst those who support remain.

The paper is organized as follows. In the next section we discuss the related Brexit literature. In Sect. 3 we provide a simple theoretical approach and discuss the literature that helps us construct the hypotheses to be tested. We then conduct the empirical analysis in Sects. 4 to 6 and finish with some concluding comments.

2 Related Brexit literature

Broadly, two types of literature have emerged from the referendum. The first is concerned with the characteristics of those who voted and theories as to why they voted the way they did. The second literature is concerned with the consequences of Brexit in terms of future EU-UK relations, UK relationships with the rest of the world and the implications for the future of the UK economy, governance and indeed the sustainability of the UK itself (Aidt et al., 2021; Born et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2018; Johnson & Mitchell, 2017; Sampson, 2017). The analysis presented here falls into the first group by focusing on the referendum itself also with attention to the characteristics and motivation of non-voters. However, it also touches discussions about the future if the referendum triggered attitudinal changes toward voting.

The contrasting characteristics of leave versus remain supporters have been revealed in a number of articles. Various studies confirm that low educational attainment, low income and older age were strong predictors of voting leave (Alabrese et al., 2019; Arnasson and Zoega 2018). Alabrese et al., (2019) point to additional leave voting determinants like white ethnicity, infrequent use of smartphones and the internet, receipt of public benefits, adverse health and low life satisfaction. The last of those issues likewise is studied in Powdthavee et al., (2019) and Carreras et al., (2019), who rely on prospect theory to explain why voters who felt that they had little to lose were more willing to take economic risks by voting for Brexit. That evidence stands, in contrast, to Clarke et al., (2017), who found younger people to be significantly more likely to emphasise the risks of Brexit.

A rich literature focuses more on reasons why voters vote remain and especially leave. Norris & Inglehart (2019), while acknowledging that the two are not completely separable, distinguish between economic insecurity and cultural backlash. On economic insecurity Fetzer (2019) argues that had it not been for austerity remain would have won. Liberini et al., (2019) argue that age is not as strong a predictor as is often thought, with only the very young being clearly predictable as pro remain. They argue that economic insecurity is clearer in predicting leave. Several authors point to the long run effects of globalization on industrial structure and culture, e.g., Colantone & Stanig (2018), who study the role of import shocks from China in leave voting. They also argue that those votes primarily were sociotropic rather than pocketbook responses.

Concerns about immigration fall under both economic insecurity and cultural backlash hypotheses; that influence on voting leave is highlighted in Hobolt (2016) and Ford & Goodwin (2017). Such evidence is contested because many leave voting constituencies have few immigrants, contrasting sharply with some of the strongest urban remain areas. Goodwin & Milazzo (2017) argue that the key factor is the rate of immigration at the local level and the perceived lack of control over it. Carreras (2019) argues that economic insecurity converts into cultural backlash, by showing that British citizens living in economically depressed and declining districts are more likely to develop cultural grievances and especially anti-immigrant and Eurosceptic views. The merging of economics and culture also is evident in Green et al., (2022), who argue that economic concerns influenced Brexit views perceived through the lens of relative gains and losses of various social groups. Hobolt et al., (2021) demonstrate the extent to which the referendum solidified identities and intensified polarization.

An important point, however, is that while clear demographic characteristics of leave versus remain voters, along with non-voters as a third category, can be discerned and, moreover, that the underlying motives for voting leave or remain and abstaining are identifiable, the question of the seriousness of conviction lurks in the background. Specifically, what if leave voters and non-voters regret their decisions not to vote remain? A large number of voters might argue that, had they known on 23 June, 2016, that the referendum would be so close, they would have voted and voted remain. Goodwin et al., (2020) examine the impact of remain and leave publicity campaigns on the EU referendum and find that the arguments favoring EU membership were understated. If large-scale regret is expressed, such sentiments call into question how one should interpret the implications of the empirical work on the demographic characteristics and motivations of leave voters and of non-voters. For example, should we be as quick to conclude that immigration is as major a concern if leave voters regret their choice? Or do we likewise conclude that identity with the European Union is weak among the young if they regret not voting?

3 Theoretical background

The theoretical basis for our paper lies in the interplay of two related but distinct concepts, regret and the motivations of voters. In the rational choice literature, the idea of regret can be brought to bear theoretically as an ex ante or ex post concept. Ferejohn & Fiorina (1974) relied on ‘anticipation of regret’ to explain higher voter turnout rates in elections than standard rational choice analysis would predict. The other form of regret, which the present paper follows, is ex post as studied by Bol et al., (2018). They find high levels of regret after the 2015 Canadian general election. That electoral setting is, of course, quite different from a binary referendum. Constituencies are contested by multiple parties and a voter’s favorite party may not be competitive locally, which may provoke strategic votes for the most favored of those parties that are competitive. Bol et al., (2018) rely on a mixed-utility model incorporating both instrumental and expressive preferences. The distinction is well established now in voting models (see Hamlin & Jennings 2011, 2019). Instrumental preferences concern how a voter will be affected by the policies of the winning party or ballot proposition and will be weighted in the voting decision by the voter’s expected probability of being decisive in determining the election’s outcome. Instrumental motives supply indirect benefits such that the voter votes for x to obtain an expected benefit z. An expressive benefit is the direct benefit from voting for x unrelated to an election’s actual result. Bol et al., (2018) identify two forms of regret. The first is when a voter votes expressively for their favorite party x but regrets doing so because the election proved close and their least favorite of the competitive parties won the seat. The second is when a voter votes strategically (instrumentally) for y, but regrets doing so because y either won or lost by a large margin and the voter would have been better off abstaining or voting expressively for their favorite, though uncompetitive, party x.Footnote 8

The Brexit referendum setting clearly differs from the Canadian election in that it is binary, but we can see that the first type of regret potentially is relevant. As such, a voter may vote expressively for Brexit when that vote is not decisive but regret the choice because the referendum was close. That is, instrumental and expressive preferences pulled in different directions. A realization that instrumental concerns were in retrospect more serious than many voters realized may be sufficient to weigh instrumental concerns more heavily ex post than they had been weighed ex ante when the decision to vote leave was cast expressively.Footnote 9

In addition to instrumental and expressive benefits, a third type of potential voting benefit is satisfying a sense of duty. The focus on duty stems from Riker & Ordeshook (1968) and can be a crucial factor in determining whether to vote or not. Blais & Galais (2016) explain, duty differs from instrumental and expressive concerns because it is unrelated to identifying with issues or party positions. If the sense of duty is strong enough a citizen will vote and how they vote will then be determined by instrumental and expressive concerns. For those who abstained in the Brexit referendum, a rational choice model would suggest that instrumental and expressive benefits and a sense of duty were too small to overcome the cost of voting. Research by Hur (2017) and Goodman (2018) suggests that duty may depend crucially on context. Goodman discusses the idea of ‘conditional duty’. She argues that the sense of duty to participate in an election will be affected by factors such as whether the stakes are high, how close the election is expected to be and whether major differences exist in parties or policy positions. Going into the Brexit referendum, many non-voters did not think that the outcome would be close (expecting remain to win) and possibly did not see major differences in positions (after all, many leave campaigners argued for maintaining very close alignment with the EU).Footnote 10 After the referendum, on observing how close the referendum was and that the possibility of ‘hard Brexit’ became very real, many non-voters may have revised their sense of duty upwards. The BSAS contains questions on vote motives, which include duty.Footnote 11 In our empirical section we investigate if reporting of a duty to vote rose significantly after the Brexit referendum.

We now formulate the three forms of regret that we will test empirically. We rely on a rational choice model containing the four components of discounted instrumental benefits, expressive benefits, duty and the costs of voting. A voter will vote for Brexit rather than remain if.

where p is the probability of being decisive, \({I}_{B}\) and \({I}_{R}\) are the instrumental payoffs from Brexit and Remain, and \({X}_{B}\) and \({X}_{R}\) are their expressive payoffs

Regret Type 1: The first form of regret concerns voters who voted for Brexit but would now vote Remain

Regret could materialize if, at the time of the referendum, \({X}_{B}>{X}_{R}\) and \({I}_{B}-{I}_{R}<0\) but p is perceived to be so small that \({I}_{B}-{I}_{R}\) largely is discounted. In addition, before the referendum the gap between \({I}_{B}\) and \({I}_{R}\) may have been viewed as smaller than it came to be viewed after the referendum because hard Brexit was not expected or understood. Therefore, after the referendum, the sign of (1) is reversed to negative because p is viewed as larger than it was beforehand and \({I}_{B}-{I}_{R}\) as more strongly negative

Regret Type 2: The second form of regret concerns non-voters regretting not voting and not voting remain

Here we do not need to consider conflicted voters for whom instrumental and expressive preferences are in opposition. We depict a non-voter who instrumentally and expressively favors remain. However, they abstain because the following holds

where D is duty and C is the cost of voting. For such individuals, the summation of the three types of voting benefits fails to exceed the cost of voting.Footnote 12 First, we can identify a regretful remain non-voter on instrumental and expressive issue dimensions. The reasons might be found in an appreciation, as discussed earlier, that p and the gap between \({I}_{R}\) and \({I}_{B}\) are larger than was thought at the time of the referendum. If non-voters took the EU for granted, they may have underestimated their expressive attachment to the EU in the style of ‘you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone’. So \({X}_{R}\) is revised upwards. Such issue related reflections may be sufficient to change the sign of (2).

Regret Type 3

The third form of regret is that after the 2016 referendum one observes a significant increase in citizens giving duty as an answer when asked about vote motives.

Following our earlier discussion of conditional duty, the reflection that the referendum was high-stakes, close and that sharp differences in opinions were voiced may cause D to increase in (2). Empirically, we separate those possibilities from the questions of how respondents would vote (or not) in a fresh referendum. Instead, we check to see if we observe a significant increase in the number of respondents giving duty as a motivation for voting after 2016.

4 Data

Our data have been obtained from the BSAS, which is a repeated cross-sectional survey that provides a representative sample of adults living in Great Britain. The 2017, 2018 and 2019 surveys all contained questions on whether respondents had voted in the EU Referendum as well as on how they voted. In addition, respondents were asked how they would vote if they were given the chance to vote again on the same referendum. Therefore, we rely on information from each of the three surveys by combining responses across the years in our analysis. A question on respondents’ views of voting (in a general election) likewise has been asked in several years of BSAS data.Footnote 13

Table 1 presents a cross-tabulation of how respondents would vote in a referendum categorized by each survey year against whether they voted in the referendum.Footnote 14 The table reports all answers to those questions, including the respondents who indicated that they preferred not to say, didn’t know/refused and didn’t remember whether they had voted in the referendum − 59 out of 4,994 respondents in the latter group. Only 1.7% of respondents who voted in the referendum reported that they would not vote in another referendum, compared to almost 29% of those who did not vote. In terms of the data presented in Tables 1, 56% of those who would vote if given the chance in a new referendum would vote remain and 44% would vote leave.

Table 2 reports how respondents would vote against how they actually did so in the referendum. Again, the table includes all responses to the questions. It reveals that the majority of individuals would vote in the same way they did in the EU Referendum if they were given the chance to do so again. Around 93% of remain voters would have voted in that way again. The equivalent percentage was lower for leave voters at 85%. Just under 9% of that group indicated that they would vote remain if given a chance to do so.Footnote 15 The table also indicates that more remain voters than leave voters are included in the combined samples of BSAS data on which we rely. It is a feature of survey datasets that asked about which side respondents supported in the referendum. However, the percentage of leave supporters in our sample (48.1%) is far closer to the percentage in the actual referendum (51.9%) than covered in other large representative surveys of the UK population, where the percentage supporting leave was 42.5% (Alabrese et al., 2019; Liberini et al., 2019; Curtice, 2016) argues that the BSAS provides high quality data on political and other issues because the relatively time-consuming and expensive process of random sampling that underlies the data collection process supplies a reliable method for achieving representative samples.Footnote 16

Table 3 presents the information reported in Tables 1 and 2 without the indeterminate categories such as prefer not to say, don’t know, and don’t remember. As a result, the table highlights more clearly some of the differences between leave and remain voters, as well as in comparison to non-voters. For example, almost 10% of leave voters indicated that they would vote in a different way if given the chance to do so again, compared with just under 5% of remain voters. Leave voters also were more likely to indicate that they would not vote if given another chance. The percentage of non-voters indicating that they would vote remain if they were able to vote again was 20 points higher than the percentage indicating that they would vote leave.

5 Empirical modelling

With respect to the first type of regret, a binary logit model relating to whether respondents voted in the referendum is estimated to identify those voters who would have voted differently if they were given the chance to do so again. Therefore, the dependent variable takes a value of one if those who voted at the EU referendum would have voted in a different way in a second referendum (for example, leave voters in the EU referendum who would have voted remain if they had the chance to do so again or vice versa) and zero for respondents who would have voted in the same way again. The key explanatory variable in the model relates to a dummy variable that takes a value of one if the respondent voted leave at the EU referendum and zero if they voted to remain. The model also contains controls for a standard set of socioeconomic characteristics, especially those that have been found to be important in empirical studies of voting on the EU referendum. Specifically, they are gender, age, education, region, marital status, children in household, ethnicity, religion and economic position.

To test for the second type of regret outlined in the theoretical background section, we initially estimate multinomial logit models in which the dependent variable that relates to how the respondent would vote if given the chance to do so again takes one of three values. They are: (1) remain in the EU, (2) leave or (3) would not vote. Those individuals who indicated that they preferred not to say, did not know, or refused to respond have been excluded from the models that have been estimated. The first model includes individuals who voted in the EU referendum as well as those who did not, with a dummy variable entered to identify the latter group. Therefore, it is a pooled model that combines voters and non-voters.Footnote 17

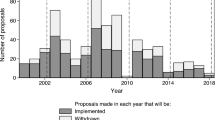

The third type of regret is examined by estimating binary logit models in which the dependent variable takes a value of one if the respondent stated that it should be everyone’s duty to vote in a general election and zero if they gave another answer. The other two possible responses are (1) that it really is not worth voting and (2) people should vote only if they care who wins, as indicated in the Appendix. Table A1 in the Appendix reports responses to the same question in every year that a general election took place since 2000.Footnote 18 The general election years are 2001, 2005, 2010 and 2015, as well as 2017. The table shows that the percentage who thought it should be everyone’s duty to vote in a general election has increased since 2010, with the percentage of respondents giving a positive response indicating that it is everyone’s duty to vote increasing from less than 68% in 2015 to more than 72% in 2017. The percentage of respondents in the other two categories, people should vote only if they care who wins and it’s really not worth voting, fell by 2.6 and 1.8% points respectively over the period. In terms of the key variable of interest, we enter a dummy variable to indicate whether the respondent appeared in the 2017 or 2015 survey, after controlling for the same explanatory variables entered into the multinomial logit models, with the exception of the children in the household dummy. We also estimate, for comparative purposes, equivalent logit models for several two-year periods in which a dummy variable is entered for the general election year in relation to the previous year in which a general election was held.

6 Results

So as to test the first form of regret, Table 4 contains the estimated coefficient and associated standard error from the key explanatory variable included in the logit model estimated with the dependent variable identifying voters who would have switched how they would have voted had they been given the chance to do so again. The coefficient attached to the variable indicating whether the individual was a leave voter in the EU Referendum, relative to being a remain voter, is positive and significant after controlling for a range of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. That finding indicates that leave voters were significantly more likely than remain voters to report that they would have voted in a different way (i.e., in favor of remain) if another referendum were held, despite the fact, that the majority of voters at the EU referendum would have voted in exactly the same way had they been given the chance to do so again. The marginal effect reported in the table indicates that the probability of respondents reporting that they would vote differently if given the chance to do so again was around 5% points higher for leave voters than for remainers. That effect is consistent with the unadjusted data reported in Table 2 where the percentage of leave voters who would have voted differently in a second referendum (9.3%) is around double that of remain voters (4.8%).

To gain further insights into voter regret following the referendum, we focus on differences between educational groups, given that Wegenast (2010) argues that educated individuals face lower information costs. We examine the influence of education in two ways, firstly by estimating the logit model reported in Table 4 separately for three educational groups: high, medium and low education and, secondly, by entering a highly educated dummy variable, rather than the full set of educational qualification dummies, in a logit regression and interacting it with the leave dummy. The results from those regressions are reported in Table 5. In terms of the separate educational groups, the leave dummy returns the largest positive coefficient and is significant at the 1% level for highly educated individuals – those who have either earned college degrees or other higher education qualifications. The leave dummy is positive significant at the 5% level for respondents with medium levels of education but insignificant for those with low levels of education. Those results indicate that more highly educated leave voters are far more likely to regret their decisions than less educated leave voters. The same finding is confirmed by observing the interaction term in the final column of Table 5: it implies that leave voters with high levels of education were significantly more likely to indicate that they would vote differently given the chance to do so again.

Table 6 presents the results from a (pooled) multinomial logit model. The coefficients and standard errors are measured relative to the base category of would vote to remain. Of most relevance to the second type of regret are the estimates associated with the explanatory variable that identifies individuals who did not vote at the referendum. The coefficient attached to that variable is negative and significant at the 5% level in the results relating to would vote leave. The finding indicates that non-voters in the EU referendum are significantly less likely to vote leave, in comparison to remain, if they were given the chance to vote again, thus providing fairly strong support in favor of the second type of regret. In contrast, the coefficient attached to non-voters is positive and significant. That result is not surprising since it shows that those who did not vote at the EU referendum are significantly more likely not to vote again rather than voting to remain.Footnote 19

Table 7 reports the results from a binary logit model that is estimated for whether the respondent stated that it should be everyone’s duty to vote in a general election. In terms of the main variable of interest, the dummy variable indicating that the individual was interviewed in 2017 (rather than 2015) is positive and significant at the 5% level after controlling for other covariates. While we accept that the evidence is suggestive and causality with the EU referendum cannot be established, the results in Table 6 can be interpreted as supporting regret type 3 in that duty significantly increases as a reported motivation for voting between 2015 and 2017. The remaining information in Table 6 relates to the changes in the incidence of respondents indicating the duty motive for voting between the other years in which a general election was held in the UK in the 21st century prior to 2017. In the other three cases, the year dummy is insignificant, which lends weight to the argument that the 2016 referendum had a significant effect on vote motivation. Heath and Goodwin (2017) analyse the 2017 general election and find that turnouts were higher in pro-remain areas with younger, more ethnically diverse and educated populations. They argue that their findings relate to the Brexit decision; they also align with our argument that civic duty has become more salient as a stated motivation for voting. Further evidence supporting that relationship is shown in Table A2 in the Appendix, where it can be seen that the change in the percentage of survey respondents indicating that it is everyone’s duty to vote was highest amongst the youngest age group (18–29 year olds) – the group that was least likely to have voted in the EU referendum.

7 Conclusion

The present paper relies on survey data to examine three forms of voter (and non-voter) regret based on the historic EU referendum that took place in the United Kingdom in June 2016. Although we report evidence of leave voters being significantly more regretful than remain voters, the majority of those who voted in the referendum would cast their votes in the same way if they were given the chance to do so again. The analysis also uncovers clear evidence of regret in relation to those individuals who did not vote. Abstention can (partly) be explained by demographics in the sense that non-voters, who were in 2016 more concentrated amongst the young, would be more likely to vote remain if given the chance to do so again. We also find that individuals who were interviewed in 2017 were significantly more likely to state that it is everyone’s duty to vote in a general election, even after controlling for whether they had voted in a general election.

Given how close the vote on Brexit was, the evidence presented for the three types of regret that we identify should be a cause for concern when interpreting the referendum’s result. In much of the debate that followed, the phrase the ‘will of the people’ was heard repeatedly and stemming from that interpretation, calls for the hard Brexit that the government subsequently pursued were justified in terms of the expression of a collective will. But the existence of widespread regret calls into question just how strongly held a large portion of expressed individual positions were, particularly the assumption of absence of will that could be attributed to those who did not vote. The rise in ‘civic duty’ as a stated motive for voting, we suggest, may be related to the referendum result and it will be interesting to see if democratic engagement also rises to avoid regret after future elections or referendums.

Perhaps, the most important implication of our analysis is that the presence of widespread regret in the Brexit referendum should serve as a warning for the design of referendums for major constitutional change. As we argued in the introduction, and think is important to reiterate, close referendums are not the same as close elections. Close elections emerge from constitutionally agreed rules of politics and if widespread regret is expressed, a chance for correction exists at the next election. And crucially, the legitimacy (which is vital for democratic performance) of a close election result is not or should not be questioned, supposing that the election was conducted fairly. A close referendum result such as Brexit changes the constitution (the rules of politics) without the prospect of overturning the result in a scheduled future vote. The absence of error-correction opportunities has led to the legitimacy of the Brexit result and subsequent decisions arising from it to be questioned. Those questions include the sustainability of the United Kingdom itself given the large vote in favor of remain in Scotland or the constitutional difficulties caused in Northern Ireland (which also voted remain) by the Northern Ireland protocol (Irish Sea Border). Anticipation of the perceived legitimacy of a close referendum result should be a central focus in the design of referendums.

Data Availability

The data used in this paper can be accessed following registration at the UK Data Service.

Code Availability

Can be requested from the corresponding author.

Notes

‘How the pollsters got it wrong on the EU referendum’, The Guardian, 24 June 2016.

‘I thought I’d put in a protest vote’: the people who regret voting leave’, The Guardian, 25 November 2017.

The turnout at the referendum was 72.2%.

‘Young people are so bad at voting - I’m disappointed in my peers’, The Guardian, 28 June 2016.

We emphasize that we are using the term ‘regret’ somewhat loosely. The common way to think about regret is having made a mistake. However, a voter may not have made a mistake if they believed they were making the correct choice, but then learned afterwards that it was the wrong choice. The data on which we rely do not allow us to distinguish between mistakes and learning because the survey respondents are not asked why they changed their minds, but we think it reasonable to group both types as ‘regret’.

Matsusaka (2020) offers Brexit as an example of a badly designed referendum. He advances three main reasons for that conclusion: First, failing to present voters with a concrete proposal in the event of leaving the EU. Second, the referendum left little room for policymakers to return to the voters with a further ballot question and, third, the use of simple majority rule in a one-off vote to determine the outcome.

‘Have UK voters changed their mind on Brexit?’, John Curtice, UK in a Changing Europe, 17 October 2019.

Courtin et al., (2018) likewise rely on instrumental (strategic) and expressive motives in the context of the first round of the French presidential elections in 2017. They report evidence for both types of regret. Collins et al., (2022) examine whether survey respondents indicated that they would vote differently in the summer of 2017 than they did in the 2016 referendum. However, the data sample they study consists of just 1500 individuals; they thus are able to identify only a small number of respondents who would have voted differently. In addition, their sample is skewed highly towards individuals who voted in the referendum and were remain supporters. In particular, 55.1% reported that they had voted remain in the referendum, 29.5% that they had voted leave and 15.4% abstained or refused to provide an answer.

We accept that other models of voting behavior have been proposed. A rationally irrational voter (Caplan, 2007) is a close cousin of the expressive voter. Caplan also starts from the premise that the probability of being decisive is very small in mass elections, so the voter is free to ignore instrumental concerns. The difference, however, is that a rationally irrational voter has rationally chosen not to incur the costs of correcting any bias they may harbor such that they believe (incorrectly) that they also are choosing in their instrumental interests. An expressive voter can understand what their instrumental and expressive preferences may be, so choosing expressively can lead to regret on the instrumental domain. On the other hand, it is hard to see how a rationally irrational voter could ever experience regret because they believed their choice to be in their instrumental interest.

fullfact.org/europe/what-was-promised-about-customs-union-referendum/.

Drinkwater & Jennings (2007) relied on the same question to help identify who might be labelled ‘expressive voters.’

Rudolph (2020) applies the Riker and Ordershook (1968) framework regarding rainfall’s contribution to increasing the cost of voting within the context of the 2016 Brexit vote.

The precise questions asked in the surveys are reported in the Appendix. The questions on whether and how respondents voted in the EU referendum were posed to around only a third of the full sample of respondents in 2018 and 2019. All of the interviews were carried out between July and November in each of the survey years.

The table reports unweighted data, as does the rest of the analysis in the paper.

Respondents who gave a different answer to the question about whether they voted on the EU referendum have been excluded from the econometric analysis.

The question has been omitted from several surveys, including those conducted in 2018 and 2019.

References

Aidt, T., Grey, F., & Savu, A. (2021). The meaningful votes: Voting on Brexit in the British House of Commons. Public Choice, 186, 587–617

Alabrese, E., Becker, S. O., Fetzer, T., & Novy, D. (2019). Who voted for Brexit? Individual and regional data combined. European Journal of Political Economy, 56, 132–150

Arnorsson, A., & Zoega, G. (2018). On the causes of Brexit. European Journal of Political Economy, 55, 301–323

Blais, A., & Galais, C. (2016). Measuring the civic duty to vote: A proposal. Electoral Studies, 41, 60–69

Bol, D., Blais, A., & Laslier, J. F. (2018). A mixed-utility theory of vote choice regret. Public Choice, 176, 461–478

Born, B., Muller, G. J., Schularick, M., & Sedlacek, P. (2019). The costs of economic nationalism: Evidence from the Brexit experiment. Economic Journal, 129, 2722–2744

Buchanan, J., & Tullock, G. (1962). The calculus of consent: Logical foundations of constitutional democracy. Ann Arbor MI: University of Michigan Press

Caplan, B. (2007). The myth of the rational voter: Why democracies choose bad policies. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press

Carreras, M. (2019). ‘What do we have to lose?’ Local economic decline, prospect theory, and support for Brexit. Electoral Studies, 62, 102094

Carreras, M., Carreras, I., Y., & Bowler, S. (2019). Long-term economic distress, cultural backlash, and support for Brexit. Comparative Political Studies, 52(9), 1396–1424

Chen, W., Los, B., McCann, P., Ortega-Argilés, R., Thissen, M., & van Oort, F. (2018). The continental divide? Economic exposure to Brexit in regions and countries on both sides of The Channel. Papers in Regional Science, 97(1), 25–54

Clarke, H. D., Goodwin, M., & Whiteley, P. (2017). Brexit: Why Britain voted to leave the European Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Colantone, I., & Stanig, P. (2018). Global competition and Brexit. American Political Science Review, 112(2), 201–218

Collins, A., Cox, A., & Torrisi, G. (2022). A picture of regret: An empirical investigation of post-Brexit referendum survey data. Rationality and Society, 34(1), 56–77

Courtin, S., Laslier, J. F., & Lebon, I. (2018). The 2017 French presidential election: Were voters happy with their first-round vote? French Politics, 16(4), 439–452

Curtice, J. (2016). The benefits of random sampling: Lessons from the 2015 UK general election. London: National Centre for Social Research

Drinkwater, S., & Jennings, C. (2007). Who are the expressive voters? Public Choice, 132, 179–189

Dustmann, C., & Preston, I. (2001). Attitudes to ethnic minorities, ethnic context and location decisions. Economic Journal, 111(470), 353–373

Fetzer, T. (2019). Did austerity cause Brexit? American Economic Review, 109(11), 3849–3886

Ferejohn, J. A., & Fiorina, M. P. (1974). The paradox of not voting: A decision theoretic analysis. American Political Science Review, 69, 920–925

Ford, R., & Goodwin, M. (2017). Britain after Brexit: A nation divided. Journal of Democracy, 28(1), 17–30

Georgiadis, A., & Manning, A. (2012). Spend it like Beckham? Inequality and redistribution in the UK, 1983–2004. Public Choice, 151(3), 537–563

Goodman, N. (2018). The conditional duty to vote in elections. Electoral Studies, 53, 39–47

Goodwin, M., Hix, S., & Pickup, M. (2020). For and against Brexit: A survey experiment of the impact of campaign effects on public attitudes toward EU membership. British Journal of Political Science, 50(2), 481–495

Goodwin, M., & Milazzo, C. (2017). Taking back control? Investigating the role of immigration in the 2016 vote for Brexit. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19(3), 450–464

Grasso, M. T., Farrall, S., Gray, E., Hay, C., & Jennings, W. (2019). Thatcher’s children, Blair’s babies, political socialization and trickle-down value change: An age, period and cohort analysis. British Journal of Political Science, 49(1), 17–36

Green, J., Hellwig, T., & Fieldhouse, E. (2022). Who gets what: The economy, relative gains and Brexit. British Journal of Political Science, 52(1), 320–338

Hamlin, A., & Jennings, C. (2011). Expressive political behaviour: Foundations, scope and implications. British Journal of Political Science, 41, 645–670

Hamlin, A., & Jennings, C. (2019). Expressive voting. In R. Congleton, B. Grofman, & S. Voigt (Eds.), Oxford handbook of Public Choice: Volume 1 (pp. 333–350). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Heath, O., & Goodwin, M. J. (2017). The 2017 general election, Brexit and the return to two-party politics: An aggregate-level analysis of the result. The Political Quarterly, 88(3), 345–358

Hobolt, S. B. (2016). The Brexit vote: A divided nation, a divided continent. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(9), 1259–1277

Hobolt, S. B., Leeper, T. J., & Tilley, J. (2021). Divided by the vote: Affective polarization in the wake of the Brexit referendum. British Journal of Political Science, 51(4), 1476–1493

Hobolt, S. B., Tilley, J., & Leeper, T. J. (2022). Policy preferences and policy legitimacy after referendums: Evidence from the Brexit negotiations. Political Behavior, 44, 839–858

Hur, A. (2017). Is there an intrinsic duty to vote? Comparative evidence from East and West Germans. Electoral Studies, 45, 55–62

Johnson, P., & Mitchell, I. (2017). The Brexit vote, economics, and economic policy. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 33, S12–S21

Liberini, F., Oswald, A. J., Proto, E., & Redoano, M. (2019). Was Brexit triggered by the old and unhappy? Or by financial feelings? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 161, 287–302

Matsusaka, J. G. (2020). Let the people rule: How direct democracy can meet the populist challenge. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press

Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit and authoritarian populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Powdthavee, N., Plagnol, A. C., Frijters, P., & Clark, A. E. (2019). Who got the Brexit blues? The effect of Brexit on subjective wellbeing in the UK. Economica, 86(343), 471–494

Riker, W. H., & Ordeshook, P. C. (1968). A theory of the calculus of voting. American Political Science Review, 62, 25–42

Rudolph, L. (2020). Turning out to turn down the EU: The mobilisation of occasional voters and Brexit. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(12), 1858–1878

Sampson, T. (2017). Brexit: The economics of international disintegration. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(4), 163–184

Sobolewska, M., & Ford, R. (2020). Brexitland: Identity, diversity and the reshaping of British politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Wegenast, T. (2010). Uninformed voters for sale: Electoral competition, information and interest groups in the US.Kyklos, 63(2),271–300

Acknowledgements

The British Social Attitudes survey has been provided by the UK Data Service (UKDS). We would also like to thank Damien Bol, Samuel Brown, Gabriel Leon, Ruben Ruiz-Rufino, Soeren Schwuchow and participants at the European Public Choice Society conference in Braga as well as four anonymous reviewers and the Editor in Chief (William F. Shughart II) for helpful comments.

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Question about whether voted on the 2016 EU referendum:

Did you manage to vote in the referendum about the European Union?

Question about how voted on the 2016 EU referendum:

Did you vote to ‘remain a member of the EU’ or to ‘leave the EU’?

Question (and responses) on voting on the EU referendum if given another chance:

If you were given the chance to vote again, how would you vote - to remain a member of the EU, to leave the EU, or would you not vote?

Question (and responses) on voting in a general election:

About general elections. Which of comes closest to your view … In a general election it’s not really worth voting OR people should vote only if they care who wins OR it’s everyone’s duty to vote?

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Drinkwater, S., Jennings, C. The Brexit referendum and three types of regret. Public Choice 193, 275–291 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-022-00997-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-022-00997-z