Abstract

New justifications for government intervention based on behavioral psychology rely on a behavioral asymmetry between expert policymakers and market participants. Public choice theory applied the behavioral symmetry assumption to policy making in order to illustrate how special interests corrupt the suppositions of benevolence on the part of policy makers. Cognitive problems associated with market choices have been used to argue for even more intervention. If behavioral symmetry is applied to the experts and not just to market participants, problems with this approach to public policy formation become clear. Manipulation, cognitive capture, and expert bias are among the problems associated with a behavioral theory of market failure. The application of behavioral symmetry to the expanding role of choice architecture will help to limit the bias in behavioral policy. Since experts are also subject to cognitive failures, policy must include an evaluation of expert error. Like the rent-seeking literature before it, a theory of cognitive capture points out the systematic problems with a theory of asymmetry between policy experts and citizens when it comes to policy making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Kahneman survived Tversky to win the prize in 2003, Robert J. Shiller won the prize in 2013 for work on asset prices informed by behavioral finance, and Richard Thaler won in 2017 for work in behavioral economics.

Lee and Clark (2018) argue that Thaler's behavioral approach affects the way political decisions are made far more widely and deeply than the ways in which market decisions are made, despite the focus on behavioral market failure.

Boettke (2011, p. 265, 269) argues when “policy experts who act like saviors” they become players in the game seeking better outcomes rather than acting like referees that merely call fouls.

Boettke and Lopez (2002, p. 112) characterize our assumptions about policymakers in terms of benevolence and omniscience; this analysis adopts that distinction.

This insight is later developed by Stigler (1971) and others.

Kahneman and Frederick (2007, p. 46) outline a two-system framework. System one is the more commonly used set of heuristics, rule-based judgment. System two is the deliberate rational analysis that more often is assumed to flow from expert judgment.

Viscusi and Gayer (2015, p. 981) question the ability of behavioral policy to improve on errors in the market through reliance on “well-meaning technocrats”.

Manipulation here is defined by Joseph Raz (1986): “Manipulation, unlike coercion, does not interfere with a person’s options. It instead perverts the way that person reaches decisions, forms preferences, or adopts goals” (quoted in full by Sunstein 2017, p. 117).

Clark and Lee (2016, p. 44) support the notion that politicians ignore the promises they make when they get elected in favor of the priorities set by interest groups. Stigler (1970) named the tendency for public expenditure to reflect the interests of the middle class, “Director’s law”. To generalize that insight, policy always will reflect the preferences of those with the strongest political voices. Shughart and Thomas (2015) argue that “regulatory rents” are distributed according to the loudest voice.

Schubert’s (2017, p. 513) “is-ought-heuristic” suggests that use of manipulation by the state gives legitimacy to policy interventions based on the fact that they are enshrined in law or enacted by government agencies.

If the same outcome were possible with a nudge or a tax, a nudge might be preferred because people value the ability to opt-out as representing respect for individual autonomy. Schubert (2017, p. 510) also discusses how nudges are more popular than taxes, but less effective in delivering policy aims. This choice of popularity over ends should result in more policy that reflects politically popular beliefs. If popular beliefs are enshrined in choice architecture, they become a form of manipulation.

Amir and Lobel (2008, p. 2126) make a distinction between “education, manipulation, and coercion”. To educate is to give the information necessary for judgment; much of behavioral policy simply replaces judgment entirely. The whole justification for nudges is that opt-outs are low-cost, which if true would merely identify a policy maker’s preferred option as the default.

The claim that the status quo is arbitrary implies a ranking of the deliberate and rational construction of rules above any sort of evolutionary process that uncovers inarticulate information. It is a preference for the explicit over the tacit. See Smith’s (2003) discussion of “Constructivist and Ecological Rationality”. Smith shared the 2003 Nobel Prize with Daniel Kahneman, who was recognized for the effect his ideas had on behavioral economics.

An ethically chosen status quo includes considerations of “welfare, autonomy, dignity, and self-government” (Sunstein 2017, p. 117).

The knowledge problem is at the core of the rejection of the new paternalism. Rizzo and Whitman (2009, p. 905), note that most policymakers simply assume away the problem of articulating and aggregating information.

Viscusi and Gayer (2015, p. 981) question the ability of behavioral policy to improve on errors in the market by relying on “well-meaning technocrats”.

One reason for this difference is a misunderstanding of the word “rational.” Following Foley (1987) a distinction exists between the “epistemic rationality” of the policymakers fully informed by scientific literature and the “instrumental rationality” of the individual actors making market decisions. The claim that policy is epistemically rational works only if omniscient policymakers write policy. By contrast, Simon (1955, p. 1956) proposed more of a trial-and-error approach to rationality based on cost of correcting flawed heuristics. For example, Kahneman and Frederick’s (2007) discussion of systems one and two fails to account for how people may update their heuristics when holding them is particularly costly. North (1993) suggests that policy is just a set of heuristics, and subject to the same test of validity—does it reduce transaction costs?

An important reason can be found for being skeptical of policy prescriptions based on laboratory experiments. Viscusi and Gayer (2015, p. 976) invoke Gary Becker’s statement on the limitations of behavioral economics and its insights into actual market actors.

For a description of how life-cycle funds have become the default investment strategy see (Viceira 2009, pp. 142–148).

Sunstein (2014, p. 17) writes “In the face of behavioral market failures, nudges are usually the best response, at least when there is no harm to others.” He purposely invokes Mill’s bias against action, the harm principle, and argues that the bias should be to nudge when behavioral errors are identified.

Congdon et al. (2011, p. 66) suggest that policymakers have a duty to structure educational choices for low-information parents. This is a great example of how policymakers might have pedagogical expertise, but undermines any consideration of when experts lack the local knowledge parents might have about their children and their local educational options.

Farelley et al. (2012) detail the rather substantial effects that cigarette taxes in New York State and New York City had on the lowest income earners, doubling the fraction of disposable income spent on smoking. See Hoffer et al. (2014) for a description of the rise of disfavored taxation as an attempt to increase tax revenues at all levels of government.

The literature on the regressive effects of regulation emphasizes that low-income persons are likely to have non-standard preferences from the point of view of policymakers. That asymmetry systematically will intensify the regulatory burden on lower income individuals and households. For an example of regressive effects in childcare policy, see Gorry and Thomas (2017); for entry regulations, see McLaughlin and Stanley (2016).

References

Akerlof, G. A. (1970). The market for “lemons”: Quality, uncertainty, and the market mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(3), 488–500.

Akerlof, G. A. (1989). The economics of illusion. Economics and Politics, 1(1), 1–15.

Amir, O., & Lobel, O. (2008). Stumble, predict, nudge: How behavioral economics informs law and policy. Columbia Law Review, 108(8), 2098–2137.

Bar-Gill, O. (2012). Competition and consumer protection: A behavioral economics account. In The pros and cons of consumer protection, pp. 12–43. Swedish Competition Authority. http://www.konkurrensverket.se/globalassets/english/publications-and-decisions/the-pros-and-cons-of-consumer-protection.pdf#page=12. Accessed March 15, 2018.

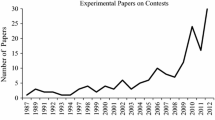

Berggren, N. (2012). Time for behavioral political economy? An analysis of articles in behavioral economics. The Review of Austrian Economics, 25, 199–221.

Boettke, P. J. (2011). Teaching economics, appreciating spontaneous order, and economics as a public science. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 80(2), 265–274.

Boettke, P. J., Caceres, Z., & Martin, A. G. (2013). Error is obvious, Coordination is the puzzle. In R. Frantz & R. Leeson (Eds.), Hayek and behavioral economics. New York: Palgrave Macmillian UK.

Boettke, P. J., & Lopez, E. (2002). Austrian economics and public choice. The Review of Austrian Economics, 15(2–3), 111–119.

Brennan, G. (2008). Psychological dimensions in voter choice. Public Choice, 137(3/4), 475–489.

Buchanan, J. M. (1999). In: G. Brennan, H. Kliemt & R. D. Tollison (Eds.), The collected works of James M. Buchanan. The logical foundations of constitutional liberty (Vol. 1). Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

Buchanan, J. M. (2004). The status of the status quo. Constitutional Political Economy, 15(2), 133–144.

Buchanan, J. M., & Tullock, G. (1962). The calculus of consent: Logical foundations of constitutional democracy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Carrigan, C. & Coglianese, C. (2016). Capturing regulatory reality: Stigler’s the theory of economic regulation. Faculty Scholarship Paper 1650. http://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/1650. Accessed March 15, 2018.

Clark, J. R., & Lee, D. R. (2016). Higher cost appeals to voters: Implications of expressive voting. Public Choice, 167(1), 37–45.

Congdon, W. J., Kling, J., & Mullaninathan, S. (2011). Policy and choice: Public finance through the lens of behavioral economics. Washington: Brookings Institution Press.

Datta-Chudhuri, M. (1990). Market failure and government failure. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 4(3), 25–39.

Farelley, M. C., Nonnemaker, J. M., & Watson, K. A. (2012). The Consequences of high cigarette excise taxes for low-income smokers. PLoS ONE, 7(9), e43838. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0043838.

Foley, R. (1987). The theory of epistemic rationality. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Gilens, M., & Page, B. I. (2014). Testing theories of American politics: Elites, interest groups, and average citizens. Perspectives on Politics, 12(3), 564–581.

Glaeser, E. (2006). Paternalism and psychology. The University of Chicago Law Review, 73(1), 1333-156.

Gorry, D., & Thomas, D. W. (2017). Regulation and the cost of childcare. Applied Economics, 49(41), 4138–4147.

Gruber, J., & Koszegi, B. (2004). Tax incidence when individuals are time-inconsistent: The case of cigarette excise taxes. Journal of Public Economics, 88(9–10), 1959–1987.

Hayek, F. A. (1945). The use of knowledge in society. The American Economic Review, 35(4), 519–530.

Hoffer, A. J., Gvillo, R., Shughart, W. F., II, & Thomas, M. D. (2017). Income-expenditure elasticities of less-healthy consumption goods. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 6(1), 127–148.

Hoffer, A. J., Shughart, W. F., & Thomas, M. D. (2014). Sin taxes and sindustry: Revenue, paternalism, and political interest. The Independent Review, 19(1), 47–64.

Kahneman, D., & Frederick, S. (2007). Frames and brains: Elicitation and control of response tendencies. Trends in Cognative Sciences, 11(2), 45–46.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. H. (1991). Anomalies: The endowment effect, loss aversion, and status quo bias. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 193–206.

Kaufmann, W., & Witteloostuijn, A. V. (2016). Do rules breed rules? Vertical rule-making cascades at the superanational, national, and organizational level. International Public Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2016.1143420.

Kaysen, C., & Turner, D. (1959). Antitrust policy: An economic and legal analysis. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Koppl, R. (2012). Experts and information choice. In R. Kopple, S. Horwitz, & L. Doubzinskis (Eds.), Experts and epistemic monopolies. Advances in Austrian economics (Vol. 17, pp. 171–202). Bingley: Emerald Publishing Group Limited.

Lee, D. R., & Clark, J. R. (2018). Can behavioral economists improve economic rationality. Public Choice, 174(1–2), 23–40.

Levy, D. M., & Peart, S. J. (2008). Thinking about analytical egalitarianism. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 67(3), 473–480.

Martin, A. (2010). Emergent politics and the power of ideas. Studies in Emergent Order, 3, 212–245.

McCubbins, M., Weingast, B. R., & Noll, R. G. (1999). The political origins of the administrative procedure act. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 15(1), 180–217.

McLaughlin, P. A. & Stanley, L. (2016). Regulation and income inequality: The regressive effects of entry regulations. Mercatus working paper. https://www.mercatus.org/publication/regulation-and-income-inequality-regressive-effects-entry-regulations-0. Accessed March 15, 2018.

Montgomery, M. R., & Bean, R. (1999). Market failure, government failure, and the private supply of public goods: The case of climate-controlled walkway networks. Public Choice, 99(3/4), 403–437.

Niskanen, W. A. (1968). The peculiar economics of bureaucracy. The American Economic Review, 58(2), 293–305.

Niskanen, W. A. (1971). Bureaucracy and representative government. New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers.

North, D. C. (1993). What do we mean by rationality? Public Choice, 77(1), 159–162.

Ostrom, E. (2000). Collective action and the evolution of social norms. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14(3), 137–158.

Pesendorfer, W. (2006). Behavioral economics comes of age: A review essay on advances in behavioral economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 44(3), 712–721.

Pigou, A. C. (1932). The economics of welfare. London: Macmillan and Co.

Posner, R. A. (1979). The Chicago school of antitrust analysis. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 127(4), 925–948.

Powell, B., & Stringham, E. P. (2009). Public choice and the economic analysis of anarchy: A survey. Public Choice, 140(3), 503–538.

Raudla, R. (2010). Governing budgetary commons: What can we learn from Elinor Ostrom? European Journal of Law and Economics, 30(3), 201–221.

Riker, W. H., & Brams, S. J. (1973). The paradox of vote trading. The American Political Science Review, 67(4), 1235–1247.

Rizzo, M. J., & Whitman, D. G. (2009). The knowledge problem of new paternalism. BYU Law Review, 4(4), 905–968.

Samuelson, P. A. (1954). The pure theory of public expenditure. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 36(4), 387–389.

Schubert, C. (2017). Exploring the (behavioral) political economy of nudging. Journal of Institutional Economics, 13(3), 499–522.

Shughart, W. F., II, & Thomas, D. (2015). Regulatory rent seeking. In R. D. Congleton & A. L. Hillman (Eds.), Companion to the political economy of rent seeking (pp. 167–186). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Shughart, W. F. II & Thomas, D. (2017). Interest groups and regulatory capture (forthcoming).

Simon, H. A. (1955). A behavioral model of rational choice. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 69(1), 99–118.

Simon, H. A. (1956). Rational choice and the structure of the environment. Psychological Review, 63(2), 129–138.

Smith, V. L. (2003). Constructivist and ecological rationality in economics. The American Economic Review, 93(3), 465–508.

Sobel, R., & Leeson, P. T. (2006). Government’s response to hurricane Katrina: A public choice analysis. Public Choice, 127(1–2), 55–73.

Stigler, G. (1970). Director’s law of public income redistribution. The Journal of Law and Economics, 13(1), 1–10.

Stigler, G. (1971). The economic theory of regulation. The Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, 2(1), 3–21.

Sunstein, C. R. (2014). Why Nudge? The politics of pibertarian paternalism. Princeton: Yale University Press.

Sunstein, C. R. (2017). The ethics of influence: Government in the age of behavioral science. New York: Cabridge University Press.

Tannenbaum, D., Fox, C. R., & Rogers, T. (2016). On the misplaced politics of behavioral policy interventions. Nature, 1, 130.

Tasic, S. (2011). Are regulators rational? Journal des Economistes et des Etudes Humaines, 17(1), 1–21.

Thaler, R., & Sunstein, C. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Princeton: Yale University Press.

Thomas, D. (2012). Regressive effects of regulation. Mercatus working paper no. 12-35. https://www.mercatus.org/publication/regressive-effects-regulation. Accessed March 15, 2018.

Tullock, G. (1967). The welfare costs of tariffs, monopolies, and theft. Western Economic Journal, 5(3), 224–232.

Tullock, G. (1981). Why so much stability? Public Choice, 37(2), 189–204.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131.

Viceira, L. M. (2009). Life cycle funds. In A. Lusardi (Ed.), Overcoming the savings slump: How to increase the effectiveness of financial education and savings programs. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Viscusi, W. K., & Gayer, T. (2015). Behavioral public choice: The behavioral paradox of government policy. Harvard Journal of Law and Policy, 38(3), 973–1007.

Wagner, R. E. (2012). Deficits, debt, and democracy: Wrestling with tragedy on the fiscal commons. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Walker, C. J. (2017). Legislating in the shadows. University of Pennslyvania Law Review, 165, 1377–1433.

Wittman, D. (1989). Why democracies produce efficient results. Journal of Political Economy, 97(6), 1395–1424.

Wittman, D. (1995). The myth of democratic failure: Why political institutions are efficient. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Anthony Gill, Edward Lopez, William F. Shughart, II, Diana W. Thomas, and the participants of the Free Market Institute at Texas Tech’s graduate brown bag workshop, in particular Ben Powell, for their helpful comments on a draft of this paper. The usual caveat applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thomas, M.D. Reapplying behavioral symmetry: public choice and choice architecture. Public Choice 180, 11–25 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-018-0537-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-018-0537-1