Abstract

We consider the regulatory problem to approve or to ban a new product/technology in the context of scientific controversy about its detrimental environmental and/or health effects. We formalize the regulator’s decision-making process as a Tullock contest (Towards a Theory of the Rent-Seeking Society, Texas A&M University Press, Texas, 1980), the contestants being an industrial lobby, representing the economic agents who have developed the new product/technology, and an environmental lobby, representing the economic agents who will be harmed by the product or technology. Assuming that the industrial lobby has private information about the unfavorable environmental and/or health effects, but can be held liable for damage ex post, we derive the equilibrium properties of the contest. In particular, we derive conditions under which it is socially preferable for the regulator to decide according to the contest’s outcome, rather than according to an ex ante cost-benefit analysis, using his prior beliefs. We find that the contest outperforms the ex ante cost-benefit analysis only if the risk of judgment-proofness is not too high.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It is assumed here that the two lobbies truly and fully represent their members’ interests. The problem of free-riding is considered in Sect. 6.

Following Rowe (2011) and Wagner (2004), the asymmetry of information exists because the industrial lobby, as the developer of the product, is in a privileged position to test the associated detrimental externalities and, as the holder of the patent, can limit the ability of third-parties to access the results. As the detrimental externalities directly determine the damage \(\delta\), but are much less likely to influence the benefit b, this justifies to postulate that the benefit is public information, whereas the damage is private information. The same assumption is used in Polinsky and Shavell (2012).

The situation where both lobbies I and E observe \(\delta\) is considered in Sect. 6. The situation where neither lobby observes \(\delta\) is not considered, because the lobbying activities then always foster a less efficient decision-making by the government.

With the latter case, the fact that lobby I can pay a judgment of only k reflects the implicit assumption that b cannot be paid back (since otherwise, the available assets would be \(b+k\)). In the literature (Shavell 1984, 2005), this is usually justified saying that b is a utility benefit. This justification does not apply here, where b is a monetary benefit by definition. Here, an alternative justification would be that b is distributed to the shareholders as dividends before the judgment.

Formally, \(\pi \left( x,y\right) =1/2\) for all \(x=y>0\), but \(\pi \left( x,y\right) =1\) when \(x=y=0\).

It is worth noting that this result is not specific to the uniform distribution of damage. In fact, it remains true for any cumulative distribution of damage \(F\left( \delta \right)\) such that \(\int \nolimits _{k}^{1}\left( \delta -k\right) dF\left( \delta \right) >0\). We thank David Malueg for pointing us this point.

The calculus is straightforward and therefore omitted here.

The calculus can be found in the “Appendix”.

We show that the expected social welfare resulting from the contest game equals \(\lim _{k\rightarrow b}s^{*}\left( b,k\right) =b^{2}/2\).

In fact, we show in the proof of Proposition 1 that \(a\left( b\right)\) is bounded below by \(\tau \left( b\right) =\left( 1/b\right) \max \left\{ 2\sqrt{1-b}(1-\sqrt{1-b}),(2\sqrt{b}-1)\right\}\).

There is an infinity of Nash equilibria, each allocating the same aggregate effort within lobby E.

The calculus can be found in the “Appendix”.

The payment capacity of lobby I at the time of the judgment is equal to his initial assets, plus his benefit, less the dividends distributed to his shareholders.

Because the discriminant \(\Delta =-4(15-8k)(1-k))^{\mathtt{{2}}}<0\) and \(\varphi \left( k,k,1\right) =\left( 3-k\right) \left( 1-k\right) ^{2}>0\).

Because the discriminant \(\Delta =4\left( 8k-7\right) \left( 1-k\right) ^{2}<0\) and \(\phi \left( k,k\right) =\left( 1-k\right) ^{3}>0\).

This is because \(X/\left( 2\left( b-k\right) +X\right)\) is decreasing in \(X=\left( 1-k\right) ^{2}\).

References

Aidt, T. S. (1998). Political internalization of economic externalities and environmental policy. Journal of Public Economics, 69, 1–16.

Aidt, T. S., & Hwang, U. (2014). To ban or not to ban: Foreign lobbying and cross-national externalities. Canadian Journal of Economics, 47(1), 272–297.

Alcalde, J., & Dahm, M. (2010). Rent seeking and rent dissipation: A neutrality result. Journal of Public Economics, 94(1/2), 1–7.

Baik, K. H. (1994). Effort levels in contests with two asymmetric players. Southern Economic Journal, 61, 367–378.

Becker, G. S. (1983). A theory of competition among pressure groups for political influence. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 98(3), 371–400.

Brennan, G., & Buchanan, J. M. (1985). The reason of rules: Constitutional political economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Congleton, R. D., Hillman, A. L., & Konrad, K. A. (2008). 40 years of research on rent seeking 1: Theory of rent seeking. New York: Springer.

Cropper, M. L., Evans, W. N., Berardi, S. J., Ducla-Soares, M. M., & Portney, P. R. (1992). The determinants of pesticide regulation: A statistical analysis of EPA decision making. Journal of Political Economy, 100, 175–197.

Gradstein, M. (1993). Rent seeking and the provision of public goods. Economic Journal, 103(420), 1236–1243.

Graichen, P. R., Requate, T., & Dijkstra, B. R. (2001). How to win the political contest: A monopolist vs. environmentalists. Public Choice, 108(3/4), 273–293.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1994). Protection for sale. American Economic Review, 84, 833–850.

Hillman, A. L., & Katz, E. (1984). Risk-averse rent seekers and the social cost of monopoly power. Economic Journal, 94, 104–110.

Hillman, A. L., & Samet, D. (1987). Dissipation of contestable rents by small numbers of contenders. Public Choice, 54, 63–82.

Hillman, A. L., & Riley, J. G. (1989). Politically contestable rents and transfers. Economics and Politics, 1(1), 17–39.

Hillman, A. L. (2013). Rent seeking. In M. Reksulak & L. Razzolini (Eds.), The Elgar companion to public choice (2nd ed., pp. 307–331). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Johnson, C., & Boersma, T. (2012). Energy (in) security in Poland: The case of shale gas. Energy Policy, 53, 389–399.

Katz, E., Nitzan, S., & Rosenberg, J. (1990). Rent-seeking for pure public goods. Public Choice, 65(1), 49–60.

Konrad, K. A. (2007). Strategy in contests: An introduction. WZB-Markets and Politics Working Paper No. SP II 2007–01.

Krueger, A. O. (1974). The political economy of the rent-seeking society. American Economic Review, 64, 291–303.

Leininger, W. (1993). More efficient rent-Seeking: A Münchhausen solution. Public Choice, 75(1), 43–62.

Long, N. V. (2013). The theory of contests: A unified model and review of the literature. European Journal of Political Economy, 32, 161–181.

Malueg, D. A., & Yates, A. J. (2004). Rent seeking with private values. Public Choice, 119(1/2), 161–178.

Morgan, J. (2003). Sequential contests. Public Choice, 116(1/2), 1–18.

Nitzan, S. (1991). Collective rent dissipation. The Economic Journal, 101(409), 1522–1534.

Nti, K. O. (1999). Rent-seeking with asymmetric valuations. Public Choice, 98, 415–430.

Polinsky, A. M., & Shavell, S. (2012). Mandatory versus voluntary disclosure of product risks. Journal of Law and Economic Organizations, 28(2), 360–379.

Rowe, E. A. (2011). Patents, genetically modified foods, and ip overreaching. SMU Law Review, 64, 859–894.

Shavell, S. (1984). A model of optimal use of liability and safety regulation. Rand Journal of Economics, 15(2), 271–280.

Shavell, S. (2005). Minimum asset requirements and compulsory liability insurance as solutions to the judgment-proof problem. Rand Journal of Economics, 36(1), 63–77.

Skaperdas, S. (1996). Contest success functions. Economic Theory, 7(2), 283–290.

Tullock, G. (1967). The welfare costs of tariffs, and theft. Western Economic Journal, 5(3), 224–232.

Tullock, G. (1980). Efficient rent seeking. In J. M. Buchanan, R. Tollison, & G. Tullock (Eds.), Towards a theory of the rent-seeking society (pp. 97–112). Texas: Texas A&M University Press.

Vigani, M., & Olper, A. (2013). GMO standards, endogenous policy and the market for information. Food Policy, 43, 32–43.

Wagner, W. E. (2004). Common ignorance: The failure of environmental law to produce needed information on health and the environment. Duke Law Journal, 53(6), 1619–1745.

Wärneryd, K. (2003). Information in conflicts. Journal of Economic Theory, 110, 121–136.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor and two anonymous referees for valuable comments. We are grateful to David Malueg for suggesting several improvement of the paper and for pointing us the generalization in footnote 9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Existence of Nash equilibrium with full compensation of damage

We show that if \(\pi \left( 0,0\right) =\alpha <1\), then no equilibrium exists when lobby E is fully compensated for damage. Indeed, if fully compensated for damage, \(y=0\) is a dominant strategy for lobby E. As a result, lobby I chooses x to maximize \(\pi \left( x,0\right) \left( b-\min \left( \delta ,k\right) \right) -x\). If \(\alpha <1\), no equilibrium strategy exists for lobby I. Indeed, the strategy \(x=0\) is dominated by any strategy x such that \(0<x<\left( 1-\alpha \right) \left( b-\min \left( \delta ,k\right) \right)\); and for all \(x>0\), the expected utility is strictly decreasing in x.

Proof of Property 1

For all b and k, let \(\phi \left( b,k\right)\) be defined by \(\phi \left( b,k\right) \equiv 8\left( b-k\right) ^{2}+\left( 1-k\right) \left( 1-2b+k^{2}\right)\).

We distinguish two cases:

-

If \(\delta \le k\), we show that

-

If \(\delta >k\), we show that

Property 1 follows directly, assuming that b and k are such that \(\phi \left( b,k\right) >0\). To obtain the last sign, denote \(\varphi \left( b,k,\delta \right) \equiv \phi \left( b,k\right) +2\left( 1-2b+k\right) \left( \delta -k\right)\). Then:

-

If \(1\,-\,2b\,+\,k\ge 0\), then \(\varphi \left( b,k,\delta \right) >0\) directly follows from \(\delta >k\) and \(\phi \left( b,k\right) >0\);

-

If \(1-2b+k<0\), then \(\varphi \left( b,k,\delta \right)\) is decreasing in \(\delta\) and is bounded below by \(\varphi \left( b,k,1\right)\).

Then remark that \(\varphi \left( b,k,1\right) =8b^{2}-2\left( 3+5k\right) b+\left( 3-k+7k^{2}-k^{3}\right)\) and that this quadratic polynomial in b is strictly positive.Footnote 19

Finally, we can check that the condition that \(\phi \left( b,k\right) >0\) is not very restrictive. Rearrange \(\phi \left( b,k\right)\) to write it as \(\phi \left( b,k\right) =8b^{2}-2\left( 1+7k\right) b+\left( 1-k+9k^{2}-k^{3}\right)\). We have:

-

If \(k<7/8\), this quadratic polynomial in b is strictly positive;Footnote 20

-

If \(k\ge 7/8\), it is positive if \(b\notin \left[ k+\left( 1-k\right) \left( 1-\sqrt{8k-7}\right) /8,k+\left( 1-k\right) \left( 1+\sqrt{8k-7}\right) /8\right]\).

\(\square\)

1.2 Calculus of the ex ante expected social surplus (private information)

The ex ante expected social surplus is

Using (7) and (8) and integrating, we get

Rearranging, this yields

where we define

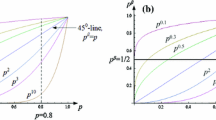

Proof of Proposition 1

We first show the following lemmas.

Lemma 1

\(f\left( \frac{k}{b}\right) <\frac{3}{2}\left( \frac{k}{b}\right) ^{2}\), for all \(0<\frac{k}{b}<1\).

Proof

Simply observe that we can write

This expression is negative since \(1-\sqrt{1-\frac{k}{b}}<\frac{k}{b}\) for all \(0<\frac{k}{b}<1\). \(\square\)

Lemma 2

If \(\phi \left( b,k\right) >0\), the expected social surplus \(s^{*}\left( b,k\right)\) is increasing in k. If \(\phi \left( b,k\right) \le 0\), \(s^{*}\left( b,k\right) <b-1/2\le {\mathrm{max}}\left( 0,b-1/2\right)\).

Proof

The first part follows directly from Property 1. To show the second part, first note that \(\phi \left( b,k\right) \le 0\) implies \(1-2b+k^{2}<0\). Then use Lemma 1 to show that

Rearrange the term under brackets to write

which proves the second part, given that \(k<b\). \(\square\)

The rest of the proof distinguishes two cases:

-

For all \(b\le 1/2\), letting \(\tau \left( b\right) \equiv 2\sqrt{1-b}\left( 1-\sqrt{1-b}\right) /b\in \left( 0,1\right)\), we show that there exists \(a\left( b\right) \in \left( \tau \left( b\right) ,1\right)\) such that \(s^{*}\left( b,a\left( b\right) b\right) =0\).

We first show that \(s^{*}\left( b,\tau \left( b\right) b\right) <0\). Indeed, Lemma 1 implies that

For all k, remark thatFootnote 21

In particular, if \(k=\tau \left( b\right) b\), we obtain (after rearrangement)

and

implying that

We then show that \(s^{*}\left( b,b\right) =b^{2}/2>0\).

From the mean-value theorem, there exists \(a\left( b\right)\) such that \(\tau \left( b\right)<a\left( b\right) <1\) and \(s^{*}\left( b,a\left( b\right) b\right) =0\). From Lemma 2, \(a\left( b\right)\) is unique and \(s^{*}\left( b,k\right) >0\) for all \(k/b>a\left( b\right)\).

-

For all \(b>1/2\), letting \(\tau \left( b\right) =\left( 2\sqrt{b}-1\right) /b\in \left( 0,1\right)\), we show that there exists \(a\left( b\right) \in \left( \tau \left( b\right) ,1\right)\) such that \(s^{*}\left( b,a\left( b\right) b\right) =b-1/2\).

We first show that \(s^{*}\left( b,\tau \left( b\right) b\right) <b-1/2\). Indeed, Lemma 1 implies that

In particular, if \(k=\tau \left( b\right) b\), we get

We then show that \(s^{*}\left( b,b\right) -\left( b-\frac{1}{2}\right) =\left( 1-b\right) ^{2}/2>0\).

From the mean-value theorem, there exists \(a\left( b\right)\) such that \(\tau \left( b\right)<a\left( b\right) <1\) and \(s^{*}\left( b,a\left( b\right) b\right) =b-1/2\). From Lemma 2, \(a\left( b\right)\) is unique and \(s^{*}\left( b,k\right) >b-1/2\), for all \(k/b>a\left( b\right)\).

1.3 Calculus of the ex ante expected social surplus (perfect information)

The ex ante expected social surplus is

Using (14) and (15) and integrating, we get

observing that \(\left( b-2\delta +k\right) /\left( b+\delta -2k\right)\) admits \(3\left( b-k\right) \ln \left( b+\delta -2k\right) -2\delta\) as an antiderivative.

Proof of Proposition 3

We show below that \(S^{*}\left( b,k\right) >\max \left( 0,b-1/2\right)\) for all \(k/b\ge \tau \left( b\right)\). We need the following lemmas.

Lemma 3

\(S^{*}\left( b,k\right)\) is increasing in k.

Proof

First use (14) and (15) to calculate the ex post expected social surplus:

Then show by differentiation that it is increasing in k:

This clearly implies that the ex ante expected social surplus \(S^{*}\left( b,k\right)\) is also increasing in k. \(\square\)

Lemma 4

\(S^{*}\left( b,k\right) >-2b+2k-bk+2b^{2}-\frac{1}{2}k^{2}.\)

Proof

By Assumption 1, we can show that

After substitution, this directly implies that

which gives the lemma after simplification. \(\square\)

The rest of the proof distinguishes two cases:

-

For all \(b\le 1/2\), using Lemma 4, we can write (after rearrangement)

$$S^{*}\left( b,\tau \left( b\right) b\right) >2\sqrt{1-b}\left( 1-\sqrt{1-b}\right) ^{3},$$which is clearly positive.

-

For all \(b>1/2\), using Lemma 4, we can write (after rearrangement)

$$S^{*}\left( b,\tau \left( b\right) b\right) -\left( b-\frac{1}{2}\right) >2\left( b+\sqrt{b}-1\right) \left( 1-\sqrt{b}\right) ^{3},$$which is clearly positive.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fauvet, P., Rouillon, S. Would you trust lobbies?. Public Choice 167, 201–219 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-016-0336-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-016-0336-5