Abstract

We study the effects of the 2008–2009 global economic crisis on the household experience of bribing public officials. The data come from the Life in Transition-2 survey, conducted in 2010 in 30 post-socialist economies of Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia. We find that households hit by crisis are more likely to bribe and, among people who bribe, crisis victims bribe a wider range of public officials than non-victims. The crisis victims are also more likely to pay bribes because public officials ask them to do so and less likely because of gratitude. The link between crisis and bribery is stronger in the poorest countries of the region. Our findings support the conjecture that public officials misuse sensitive information about crisis victims to inform bribe extortion decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See also Yamamura (2014) for the evidence that natural disasters lead to more public sector corruption at the country level.

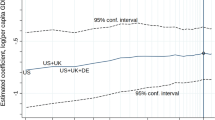

There is also a large literature on the country-level determinants of corruption, as well as on the country- and firm-level effects of corruption. See, for example, Iwasaki and Suzuki (2012), Dreher and Siemers (2009), Serra (2006) and Yamamura (2014) for the role of country-level structural reforms, capital controls, GDP per capita, political stability, colonial past and natural disasters in determining corruption. For the effects of corruption, much effort has been devoted to finding out whether corruption has a harmful or beneficial effect on outcomes such as GDP growth and firm entry. For example, Mauro (1995), Meon and Sekkat (2005) and Johnson et al. (2011) find a harmful effect of corruption on economic growth. At the same time, Dreher and Gassebner (2013) find that corruption facilitates firm entry, and Mendez (2014) shows that corrupt officials may increase firms’ compliance with regulations.

Whether corruption persists in the long-run is open to some debate in the literature. For example, whilst Rose-Ackerman (1978) and Shleifer and Vishny (1993) argue that competition among officials reduces corruption to zero, this outcome depends on how powerful the central authority is (Priks 2012).

On the downside, the respondents may be reluctant to talk about the actual corruption exchanges in which they were involved. However, the stigma associated with honestly answering questions about bribery may be lower in high-corruption (such as transition economies) than low-corruption countries (such as industrialised Western democracies). This is because in high-corruption countries bribery is viewed as inevitable and part of the system (Hunt 2007).

The main dataset includes Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, former Yugoslavian Republic of Macedonia, Moldova, Mongolia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Tajikistan, Turkey, Ukraine and Uzbekistan.

Table A1 of the online appendix contains information on the share of respondents who contacted a particular type of public official and the number of respondents who paid a bribe.

This distribution of answers excludes respondents who did not provide an answer to the question (6.6 % of the sample). The crisis questions non-respondents, however, are not excluded from the econometric analysis—all regressions, looking at general effects of crisis, contain a crisis-question-missing-value dummy (results for this variable are not reported and are available on request).

These coefficients are Pearson correlations. We have also calculated tetrachoric correlations (a technique suitable for calculating correlations between dichotomous variables); they did not exceed 0.35. In addition, we have tested for multicollinearity by obtaining the variance inflation factors (VIF) after estimating the model. The VIFs for the different effects of crisis ranged from 1.03 to 1.24, being well below the critical value of 10.

The post-estimation Variance Inflation Factor analysis, again, suggests that the multicollineraity is unlikely to be an issue: VIFs for the expenditure effect variables ranged from 1.08 to 1.35, which is lower than the critical value of 10.

The respondents were asked, “Please imagine a ten-step ladder where on the bottom, the first step, stand the poorest 10 % people in our country, and on the highest step, the tenth, stand the richest 10 % of people in our country. On which step of the ten is your household today?”.

The wealth index was constructed using principal component analysis. Unfortunately, the survey does not contain information on the actual household (or individual) income. We considered using information on household expenditures on different goods (food, utilities, transport, education, health, clothing and durable goods) as a proxy for household income, but decided against it, as the “do not know”/non-response rate for several of these expenditure categories is as high as 18 % (and much higher for particular countries – e.g., 66 % missing answers for the expenditure on durable goods in Uzbekistan), and the proportion of missing values of the composite expenditure variable is 46 %.

We have also estimated the model with Poisson regression; the results are consistent with the OLS model and are available on request.

We have also checked for possible non-linearities in the wealth-bribery relationship, by estimating the models with the wealth index and its square. The results suggest an inverted U-shaped relationship, with the implied inflection point equal to 2.89 and 1.34 on the wealth index scale for the models explaining general bribery and the number of officials bribed, respectively. It is should be noted that only two percent of respondents had a wealth indexes above 2.89 and those of 15 percent exceeded 1.34. This effectively means that, for the overwhelming majority of our sample, the likelihood of bribery and the range of public officials bribed was increasing with household wealth.

This finding, however, should be interpreted with caution. Some people habitually complain about everything, including being the crisis victims and the extortion targets for public officials. Unfortunately, with the present data, we are not able to isolate such potential “kvetching” effects (Kaufmann and Wei 2000 p.16); the use of longitudinal data, which would allow isolating unobserved personality trait effects, represents a possible solution and a way forward.

In this paper we concentrate on the effects of crisis on the likelihood of bribery, controlling for individual-level characteristics. The discussion of these individual-level characteristics on bribery in Western Europe can be found in our related work (Ivlevs and Hinks 2014).

The income groups were created according to the World Bank country income classification for 2009.

References

Barr, B., Taylor-Robinson, D., Scott-Samuel, A., McKee, M., & Stuckler, D. (2012). Suicides associated with the 2008-10 economic recession in England: time trend analysis. British Medical Journal, 345, e5142.

Dreher, A., & Gassebner, M. (2013). Greasing the wheels? The impact of regulations and corruption on firm entry. Public Choice, 155, 413–432.

Dreher, A., & Siemers, L. (2009). The nexus between corruption and capital account restrictions. Public Choice, 140, 245–265.

Gatti, R., Paternostro, S., & Rigolini, J. (2003). Individual attitudes toward corruption: do social effects matter? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3122. Washington: World Bank.

Gili, M., Roca, M., Basu, S., McKee, M., & Stuckler, D. (2013). The mental health risks of economic crisis in Spain: evidence from primary care centres, 2006 and 2010. European Journal of Public Health, 23, 103–108.

Guerrero, M.A., & Rodriguez-Oreggia, E. (2008). On the individual decisions to commit corruption: A methodological complement. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 65, 357–372.

Hunt, J. (2007). How corruption hits people when they are down. Journal of Development Economics, 84(2), 574–589.

Hunt, J., & Laszlo, S. (2012). Is bribery really regressive? Bribery’s costs, benefits, and mechanisms. World Development, 40(2), 355–372.

Ivlevs, A., & Hinks, T. (2014). Bribing behavior and sample selection: evidence from post-socialist countries and Western Europe. Journal of Economics and Statistics/Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik (forthcoming).

Iwasaki, I., & Suzuki, T. (2012). The determinants of corruption in transition economies. Economics Letters, 114, 54–60.

Johnson, N. D., LaFountain, C. L., & Yamarik, S. (2011). Corruption is bad for growth (even in the United States). Public Choice, 147(3–4), 377–393.

Katikireddi, S. V., Niedzwiedz, C. L., & Popham, F. (2012). Trends in population mental health before and after the 2008 recession: a repeat cross-sectional analysis of the 1991–2010 Health Surveys of England. British Medical Journal Open, 2(5), e001790.

Kaufmann, D., & Wei, S-J. (2000). Does ‘grease money’ speed up the wheels of commerce? International Monetary Fund Policy Working Paper, WP/00/64.

Klitgaard, R. (1988). Controlling corruption. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Mauro, P. (1995). Corruption and growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110, 681–712.

Mendez, F. (2014). Can corruption foster regulatory compliance? Public Choice, 158, 189–207.

Méon, P.-G., & Sekkat, K. (2005). Does corruption grease or sand the wheels of growth? Public Choice, 122(1), 69–97.

Mocan, N. (2008). What determines corruption? International evidence from micro data. Economic Inquiry, 46(4), 493–510.

Priks, M. (2012). Competition among officials and the abuse of power. Public Choice, 150, 425–438.

Rose-Ackerman, S. (1978). Corruption: a study in political economy. New York: Academic Press.

Roth, F., Nowak-Lehmann, F., & Otter, T. (2011). Has the financial crisis shattered citizens’ trust in national and European governmental institutions? Evidence from the EU member states, 1999–2010. Centre for European Policy Studies Working Document.

Serra, D. (2006). Empirical determinants of corruption: a sensitivity analysis. Public Choice, 126, 225–256.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1993). Corruption. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108, 599–617.

Sobotka, T. V., Skirbekk, V., & Philipov, D. (2011). Economic recession and fertility in the developed world. Population and Development Review, 37(2), 267–306.

Steves, F. (Ed.). (2011). Life in transition: after the crisis. London: European Bank for Reconstruction and Development & World Bank.

Tavits, M. (2010). Why do people engage in corruption? The case of Estonia. Social Forces, 88(3), 1257–1279.

Truex, R. (2011). Corruption, attitudes, and education: survey evidence from Nepal. World Development, 39(7), 1133–1142.

Yamamura, E. (2014). Impact of natural disaster on public sector corruption. Public Choice, 161(3–4), 385–405.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editors, two anonymous referees, and the conference participants at the Universities of Aston, Cambridge and Queen Mary for many useful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ivlevs, A., Hinks, T. Global economic crisis and corruption. Public Choice 162, 425–445 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-014-0213-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-014-0213-z