Abstract

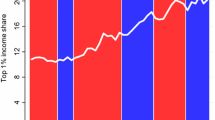

This paper theorizes that the impact of ideology on the size of US state governments increases with state income. This idea is tested using state-level ideology data derived from the voting behavior of state congressional representatives. Empirically the interaction of ideology and mean income is a key determinant of state government size. At 1960s levels of income the impact of ideology is negligible. At 1997 levels of income a one standard-deviation move towards the left of the ideology spectrum increases state government size by about half a standard deviation. Estimated income elasticities differentiated by state and time are found to be increasing with ideology and diminishing with income, as predicted by the theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

An extensive literature argues that differences in political culture, expressed in the form of differing political ideologies, play a role in determining the size and scope of government in mixed economies. Acemoglu (2005) makes this point in his critique of Persson and Tabellini (2003, 2004). Using international data Cameron (1978), Cusack (1997) and Tavits (2004) all find a relationship between government size and ideology using fixed ideological data (i.e., defined by parties in power). Pickering and Rockey (2011) found this relationship to be strongly conditional on income levels.

In the context of US states there is an important distinction between tax revenue and public sector expenditure, as the latter is funded in part by transfers from the Federal government. This issue is addressed below.

In common with this paper and Besley and Case (2003), Bjørnskov and Potrafke also emphasize the importance of divided government, as discussed below.

The relevant results in Besley and Case (2003:41, 43) are in their Tables 8 and 9. Knight (2000) also finds that Democrat (Republican) control of both houses leads to higher (lower) taxes rates relative to state GDP, Besley and Case (1995) find that Democrats raise taxes and spending when working under term limits and Rogers and Rogers (2000) also find that Democrat control in the house is associated with larger government. Blais et al. (1993) find that party identity plays a small role in driving government spending using international data.

In this paper we prefer the term ‘policy platform’, but the wider literature often prefers ‘manifesto’. For our purposes, the terms are equivalent.

It is simplest to think of the public good as rival and excludable rather than a public good of the Samuelson variety.

Note that given the properties of F and G the equilibrium is unique and bounded, i.e., 0≤t ∗<1.

As well as entering (2) directly, c m and g also depend on \(\overline{y}\), hence restrictions on the third-order derivatives are required.

Meltzer and Richard (1983) also employ this functional form.

Total taxes are defined as the sum of sales, income and corporate taxes. The data are described in full in Besley and Case (2003).

The liberal-conservative dimension links with the above theory wherein ideology is defined by preferences for the public good relative to private consumption. For example, Saunders (2004) writes that “A liberal… favors activist government and has a progressive vision of the state’s role… through necessarily higher taxes” whilst “the conservative tends to oppose an activist government… (and) usually favors lower… taxes. Simply put a pure conservative believes in the least government possible at all levels.”

Note that because Berry et al. (2010) have since updated their ideology data, estimation is now feasible for the full sample whereas Besley and Case (2003), only had access to ideology data ending in 1993. The ideology data begin in 1960. Following Besley and Case (2003) Nebraska is omitted from the analysis because it has a unicameral non-partisan legislature.

This follows immediately from the state budget constraint.

Besley and Case (2003) also used quadratic terms in income and state population but we have dropped these terms for two reasons. Firstly, they are highly collinear with the other variables. In particular the Variance Inflation Term (VIF) for state income is 180 when column 1 of Table 4 is extended to include the squared terms. Secondly, the theory is concerned with income elasticity and inferences are more straightforward when just the linear term is included.

When state expenditure is the dependent variable, the impact of ideology becomes significant at $9,000.

Note that the state expenditure data include observations from 1998, thus increasing the sample size by 47.

This specification follows from (7), and is similar to that used by Bjørnskov and Potrafke (2011) with the distinction, following from the theory, that the difference in government size is regressed on the difference in ideology and its interaction with income, as opposed to ideology measured in levels.

In particular, we estimated column 2 of Table 13, column 4 of Table 14 and column 1 of Table 15 in Besley and Case (2003), with the inclusion of the lagged dependent variable, and using clustered robust standard errors. In this more demanding econometric specification, only the super majority rule survived in terms of statistical significance. These results are available on request.

Ideally, we would include all of institutional variables at once. The problem with this approach is that many of these variables are correlated with each other. Besley and Case (2003) also take the approach of examining particular institutions in isolation.

It is not possible to adequately distinguish between the effects of split and vetosplit as they are highly correlated.

References

Acemoglu, D. (2005). Constitutions, politics and economics: a review essay on Persson and Tabellini’s “The economic effects of constitutions”. Journal of Economic Literature, 43, 1025–1048.

Alesina, A., & Angeletos, G.-M. (2005). Fairness and redistribution: US vs Europe. American Economic Review, 95, 960–980.

Alesina, A., Glaeser, E., & Sacerdote, B. (2001). Why doesn’t the US have a European-style welfare state? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2, 187–277.

Arellano, M. (2003). Panel data econometrics: advanced texts in econometrics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baumol, W. J. (1967). Macroeconomics of unbalanced growth: the anatomy of urban crisis. American Economic Review, 57, 415–426.

Benabou, R. (2008). Ideology. Journal of the European Economic Association, 6, 321–352.

Benoit, K., & Laver, M. (2007). Estimating party policy positions: comparing expert surveys and hand-coded content analysis. Electoral Studies, 26, 90–107.

Berry, W. D., Ringquist, E. J., Fording, R. C., & Hanson, R. L. (1998). Measuring citizen and government ideology in the American States 1960–1993. American Journal of Political Science, 42, 327–348.

Berry, W. D., Fording, R. C., Ringquist, E. J., Hanson, R. L., & Klarner, C. E. (2010). Measuring citizen and government ideology in the U.S. States: a re-appraisal. State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 10, 117–135.

Besley, T., & Case, A. (1995). Does political accountability affect economic policy choices? Evidence from gubernatorial term limits. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110, 769–798.

Besley, T., & Case, A. (2003). Political institutions and policy choices: evidence from the United States. Journal of Economic Literature, 61, 7–73.

Bjørnskov, C., Potrafke, N. (2011). The size and scope of government in the US States: does political ideology matter? Unpublished manuscript.

Blais, A., Blake, D., & Dion, S. (1993). Do parties make a difference? Parties and the size of government in liberal democracies. American Journal of Political Science, 37(1), 40–62.

Braumoeller, B. F. (2004). Hypothesis testing and multiplicative interaction terms. International Organization, 58(4), 807–820 (Autumn).

Bruno, G. S. F. (2005a). Approximating the bias of the LSDV estimator for dynamic unbalanced panel data models. Economics Letters, 87, 361–366.

Bruno, G. S. F. (2005b). Estimation and inference in dynamic unbalanced panel-data models with a small number of individuals’. The Stata Journal, 5, 473–500.

Budge, I., Klingemann, H.-D., Volkens, A., Bara, J., & Tanenbaum, E. (2001). Mapping policy preferences: estimates for parties, electors and governments 1945–1998. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cameron, D. R. (1978). The expansion of the public economy: a comparative analysis. American Political Science Review, 72, 1243–1261.

Choi, I. (2001). Unit root tests for panel data. Journal of International Money and Finance, 20, 249–272.

Cusack, T. R. (1997). Partisan politics and public finance: changes in public spending in the industrialized democracies, 1955–1989. Public Choice, 91, 375–395.

Dye, T. R. (1984). Party and policy in the states. The Journal of Politics, 46, 1097–1116.

Erikson, R. S., Wright, G. C. Jr., & McIver, J. P. (1989). Political parties, public opinion and state policy in the United States. American Political Science Review, 83, 729–750.

Garand, J. C. (1988). Explaining government growth in the U.S. States. American Political Science Review, 82, 837–849.

Gilligan, T. W., & Matsusaka, J. G. (1995). Deviations from constituent interests: the role of legislative structure and political parties in the States. Economic Inquiry, 33, 383–401.

Hadri, K. (2000). Testing for stationarity in heterogeneous panel data. Econometrics Journal, 3, 148–161.

Hansen, M. E. (2008). Back to the archives? A critique of the danish part of the manifesto dataset. Scandinavian Political Studies, 31, 201–216.

Hlouskova, J., & Wagner, M. (2006). The performance of panel unit root and stationarity tests: results from a large scale simulation study. Econometric Reviews, 25, 85–116.

Im, K. S., Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y. (2003). Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics, 115, 53–74.

Kim, H.-M., & Fording, R. C. (1998). Voter ideology in western democracies, 1946–1989. European Journal of Political Research, 33, 73–97.

Kim, H.-M., & Fording, R. C. (2003). Voter ideology in western democracies: an update. European Journal of Political Research, 42, 95–105.

Kim, J., & Gerber, B. (2005). Bureaucratic leverage of policy choice: explaining the dynamics of state level reforms in telecommunications regulation. Policy Studies Journal, 33, 613–633.

Kiviet, J. F. (1995). On bias, inconsistency, and efficiency of various estimators in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 68, 53–78.

Knight, B. G. (2000). Super-majority voting requirements for tax increases: evidence from the states. Journal of Public Economics, 76, 41–67.

Langer, L., & Brace, P. (2005). The preemptive power of state supreme courts: adoption of abortion and death penalty legislation. Policy Studies Journal, 33, 317–340.

Magalhães, L. M., & Ferrero, L. (2010). Separation of powers or ideology? What determines the tax level? Theory and evidence from the US States. Bristol Economics Discussion Papers, 10/620.

Meltzer, A. H., & Richard, S. F. (1981). A rational theory of the size of government. Journal of Political Economy, 89, 914–927.

Meltzer, A. H., & Richard, S. F. (1983). Tests of a rational theory of the size of government. Public Choice, 41, 403–418.

Nickell, S. (1981). Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrica, 49(6), 1417–1426.

Pelizzo, R. (2003). Party positions or party direction? An analysis of party manifesto data. West European Politics, 26, 67–89.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2003). The economic effects of constitutions. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2004). Constitutional rules and fiscal policy outcomes. American Economic Review, 94(1), 25–45.

Pickering, A. C., & Rockey, J. (2011). Ideology and the growth of government. Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(3), 907–919.

Piketty, T. (1995). Social mobility and redistributive politics. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110, 551–584.

Rogers, D. L., & Rogers, J. H. (2000). Political competition and state government size: do tighter elections produce looser budgets? Public Choice, 105, 1–21.

Roodman, D. (2009). How to do xtabond2: an introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. The Stata Journal, 9, 86–136.

Saunders, K. L. (2004). Ideology in American public opinion. In J. G. Geer (Ed.), Public opinion and polling around the world: a historical encyclopedia (Vol. 2). Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO Publishers.

Shipan, C. R., & Volden, C. (2006). Bottom-up federalism: the diffusion of anti-smoking policies from US cities to states. American Journal of Political Science, 50, 825–843.

Smith, T. W. (1990). Liberal and conservative trends in the United States since world war II. Public Opinion Quarterly, 54, 479–507.

Songer, D. R., & Ginn, H. M. (2002). Assessing the impact of presidential and home state influences on judicial decisionmaking in the United States courts of appeals. Political Research Quarterly, 55, 299–328.

Soss, J., Schraum, S. F., Vartanian, T. P., & O’Brien, E. (2001). Setting the terms of relief: explaining state policy choices in the devolution revolution. American Journal of Political Science, 45, 378–395.

Tavits, M. (2004). The size of government in majoritarian and consensus democracies. Comparative Political Studies, 37, 340–359.

Wagner, A. (1893). Grundlegung der politischen Oekonomie (3rd ed.). Leipzig: C. F. Winter.

Winters, R. F. (1976). Party control and policy change. American Journal of Political Science, 20, 597–636.

Wood, D. B., & Theobald, N. A. (2003). Political responsiveness and equity in public education finance. The Journal of Politics, 65, 718–738.

Acknowledgements

We thank Tim Besley and Richard Fording for making their data available and seminar participants at the University of York. We also thank the editor and the anonymous referees. The standard disclaimer applies. Part of this work took place whilst Rockey was visiting the Institut d’Economia de Barcelona and he is grateful for their generous support and hospitality.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pickering, A.C., Rockey, J. Ideology and the size of US state government. Public Choice 156, 443–465 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-012-0026-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-012-0026-x