Abstract

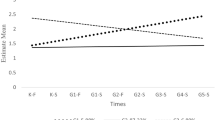

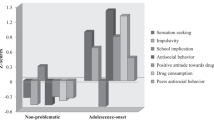

We inquire how early in childhood children most at risk for problematic patterns of internalizing and externalizing behaviors can be accurately classified. Yearly measures of anxiety/depressive symptoms and aggressive behaviors (ages 6–13; n = 334), respectively, are used to identify behavioral trajectories. We then assess the degree to which limited spans of yearly information allow for the correct classification into the elevated, persistent pattern of the problem behavior, identified theoretically and empirically as high-risk and most in need of intervention. The true positive rate (sensitivity) is below 70% for anxiety/depressive symptoms and aggressive behaviors using behavioral information through ages 6 and 7. Conversely, by age 9, over 90% of the high-risk individuals are correctly classified (i.e., sensitivity) for anxiety/depressive symptoms, but this threshold is not met until age 12 for aggressive behaviors. Notably, the false positive rate of classification for both high-risk problem behaviors is consistently low using each limited age span of data (< 5%). These results suggest that correct classification into highest risk groups of childhood problem behavior is limited using behavioral information observed at early ages. Prevention programming targeting those who will display persistent, elevated levels of problem behavior should be cognizant of the degree of misclassification and how this varies with the accumulation of behavioral information. Continuous assessment of problem behaviors is needed throughout childhood in order to continually identify high-risk individuals most in need of intervention as behavior patterns are sufficiently realized.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The data used in this research are available by request from the principle investigators of the Rochester Intergenerational Study and the University at Albany. Current efforts are underway to publish the data through ICPSR in line with the funding requirements.

Notes

Since ages in the first wave of data collection for the RIGS study ranged from 2 to 13 years old (Thornberry et al. 2018), all RIGS participants who were 8 years or older at the start of RIGS were excluded from the analysis (N = 92). Additionally, some RIGS children were too young to be included in the analysis as they were not at least 12 years of age in 2017 (n = 32), the last year of completed data collection. The remaining children had missing information in more than one interview during the defined observation period (n = 81).

As an alternative to GBTM, we could have instead modeled the trajectories using growth mixture modeling (GMM; Muthén 2001). As GMM principally distinguishes latent classes by the shape of the curve, with within-class variation captured by a variance component for the growth parameter(s), this approach tends to yield fewer latent classes than GBTM. In the interest of parsimony for classification (i.e., membership in a latent class as a binary risk factor), we thus choose to use GBTM which would likely yield distinct latent classes, specifically a high-level group, rather than a continuous latent construct which would be harder to classify in our schema.

To be clear, the Bayes rule calculation used to calculate the posterior probabilities at earlier ages is a function of (a) the growth parameters from the model estimated using all time points, and (b) the vector of data observed only through age t, rather than age T. The former implies greater precision of the actual parameter estimates (see Petras 2016).

References

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the child behavior checklist/4-18.

Achenbach, T. M., & Edelbrock, C. S. (1979). The classification of child psychopathology: A review and analysis of empirical efforts. Psychological Bulletin, 85(6), 1275–1301.

Amato, P. R. (2001). Children of divorce in the 1990s: An update of the Amato and Keith (1991) meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 15(3), 355.

Bates, J. E., Pettit, G. S., Dodge, K. A., & Ridge, B. (1998). Interaction of temperamental resistance to control and restrictive parenting in the development of externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychology, 34(5), 982.

Bennett, K. J., & Offord, D. R. (2001). Screening for conduct problems: Does the predictive accuracy of conduct disorder symptoms improve with age? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(12), 1418–1425.

Bennett, K. J., Lipman, E. L., Brown, S., Racine, Y., Boyle, M. H., & Offord, D. R. (1999). Predicting conduct problems: Can high-risk children be identified in kindergarten and grade 1? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(4), 470.

Broidy, L. M., Nagin, D. S., Tremblay, R. E., Bates, J. E., Brame, B., Dodge, K. A., et al. (2003). Developmental trajectories of childhood disruptive behaviors and adolescent delinquency: A six-site, cross-national study. Developmental Psychology, 39(2), 222.

Campbell, S. B., Spieker, S., Burchinal, M., Poe, M. D., & NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (2006). Trajectories of aggression from toddlerhood to age 9 predict academic and social functioning through age 12. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(8), 791–800.

Campbell, S. B., Spieker, S., Vandergrift, N., Belsky, J., Burchinal, M., & Network, N. I. C. H. D. E. C. C. R. (2010). Predictors and sequelae of trajectories of physical aggression in school-age boys and girls. Development and Psychopathology, 22(1), 133–150.

Clemans, K. H., Musci, R. J., Leoutsakos, J. M. S., & Ialongo, N. S. (2014). Teacher, parent, and peer reports of early aggression as screening measures for long-term maladaptive outcomes: Who provides the most useful information? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(2), 236.

Costello, E. J., Pine, D. S., Hammen, C., March, J. S., Plotsky, P. M., Weissman, M. M., Biederman, J., et al. (2002). Development and natural history of mood disorders. Biological Psychiatry, 52(6), 529–542.

Davies, P., & Windle, M. (2001). Interparental discord and adolescent adjustment trajectories: The potentiating and protective role of intrapersonal attributes. Child Development, 72(4), 1163–1178.

Dodge, K. A., & Pettit, G. S. (2003). A biopsychosocial model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 39(2), 349.

Dodge, K. A. (2014). A social information processing model of social competence in children. In Cognitive perspectives on children's social and behavioral development (pp. 85–134). Psychology Press.

Dodge, K. A., Malone, P. S., Lansford, J. E., Miller, S., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (2009). A dynamic cascade model of the development of substance-use onset. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 74(3), vii–119.

Fekkes, M., Pijpers, F. I., Fredriks, A. M., Vogels, T., & Verloove-Vanhorick, S. P. (2006). Do bullied children get ill, or do ill children get bullied? A prospective cohort study on the relationship between bullying and health-related symptoms. Pediatrics, 117(5), 1568–1574.

Glew, G., Rivera, F., & Feudtner, C. (2000). Bullying: Children hurting children. Pediatrics in Review, 21, 13–190.

Haapasalo, J., & Tremblay, R. E. (1994). Physically aggressive boys from ages 6 to 12: Family background, parenting behavior, and prediction of delinquency. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62(5), 1044.

Hill, L. G., Coie, J. D., Lochman, J. E., & Greenberg, M. T. (2004). Effectiveness of early screening for externalizing problems: Issues of screening accuracy and utility. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(5), 809.

Hussong, A., Ennett, S., & Faris, R. (2016). Peer mechanisms in the internalizing pathways to alcohol abuse. Alcoholism-Clinical and Experimental Research, 40, 54A.

Janosz, M., Archambault, I., Morizot, J., & Pagani, L. S. (2008). School engagement trajectories and their differential predictive relations to dropout. Journal of Social Issues, 64(1), 21–40.

Kokko, K., Tremblay, R. E., Lacourse, E., Nagin, D. S., & Vitaro, F. (2006). Trajectories of prosocial behavior and physical aggression in middle childhood: Links to adolescent school dropout and physical violence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16(3), 403–428.

Loeber, R. (1991). Antisocial behavior: More enduring than changeable? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(3), 393–397.

Loeber, R., Farrington, D. P., & Petechuk, D. (2003). Child delinquency: Early intervention and prevention. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Leve, L. D., Kim, H. K., & Pears, K. C. (2005). Childhood temperament and family environment as predictors of internalizing and externalizing trajectories from ages 5 to 17. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33(5), 505–520.

Lizotte, A. J., Chard-Wierschem, D. J., Loeber, R., & Stern, S. B. (1992). A shortened Child Behavior Checklist for delinquency studies. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 8(2), 233–245.

Lochman, J. E. (1995). Screening of child behavior problems for prevention programs at school entry. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63(4), 549.

Lussier, P., Farrington, D. P., & Moffitt, T. E. (2009). Is the antisocial child father of the abusive man? A 40-year prospective longitudinal study on the developmental antecedents of intimate partner violence. Criminology, 47(3), 741–780.

Masse, L. C., & Tremblay, R. E. (1997). Behavior of boys in kindergarten and the onset of substance use during adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54(1), 62–68.

Meehl, P. E., & Rosen, A. (1955). Antecedent probability and the efficiency of psychometric signs, patterns, or cutting scores. Psychological Bulletin, 52(3), 194.

Mihalic, S. F., & Elliott, D. S. (2015). Evidence-based programs registry: Blueprints for healthy youth development. Evaluation and Program Planning, 48, 124–131.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100(4), 674–701.

Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Dickson, N., Silva, P., & Stanton, W. (1996). Childhood-onset versus adolescent-onset antisocial conduct problems in males: Natural history from ages 3 to 18 years. Development and Psychopathology, 8(2), 399–424.

Muthén, B. (2001). Second-generation structural equation modeling with a combination of categorical and continuous latent variables: New opportunities for latent class/latent growth modeling. In L. M. Collins & A. Sayer (Eds.), New methods for the analysis of change (pp. 291–322). Washington, D.C.: APA.

Nagin, D. S. (2005). Group-based modeling of development. Harvard University Press.

NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (2004). Trajectories of physical aggression from toddlerhood to middle childhood: Predictors, correlates, and outcomes. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 69(4), vii–vi1.

Patterson, G. R., & Yoerger, K. (1993). Developmental models for delinquent behavior.

Patterson, G. R., DeBaryshe, B. D., & Ramsey, E. (2017). A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. In Developmental and life-course criminological theories (pp. 29–35). Routledge.

Petras, H. (2016). Longitudinal assessment design and statistical power for detecting an intervention impact. Prevention Science, 17(7), 819–829.

Poulin, F., Dishion, T. J., & Burraston, B. (2001). 3-year iatrogenic effects associated with aggregating high-risk adolescents in cognitive-behavioral preventive interventions. Applied Developmental Science, 5(4), 214–224.

Roeser, R. W., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Schooling and mental health. In Handbook of developmental psychopathology (pp. 135–156). Boston, MA: Springer.

Roeder, K., Lynch, K. G., & Nagin, D. S. (1999). Modeling uncertainty in latent class membership: A case study in criminology. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 94(447), 766–776.

Roland, E. (2002). Bullying, depressive symptoms and suicidal thoughts. Educational Research, 44(1), 55–67.

Seals, D., & Young, J. (2003). Bullying and victimization: Prevalence and relationship to gender, grade level, ethnicity, self-esteem, and depression. Adolescence, 38(152), 735–747.

Sterba, S. K., Prinstein, M. J., & Cox, M. J. (2007). Trajectories of internalizing problems across childhood: Heterogeneity, external validity, and gender differences. Development and psychopathology, 19(2), 345–366.

Thornberry, T. P., Henry, K. L., Krohn, M. D., Lizotte, A. J., & Nadel, E. L. (2018). Key findings from the Rochester intergenerational study. In V. Eichelsheim & S. van de Weijer (Eds.), Intergenerational continuity of criminal and antisocial behavior: An international overview of current studies. Oxford: Routledge.

Tremblay, R. E., Nagin, D. S., Séguin, J. R., Zoccolillo, M., Zelazo, P. D., Boivin, M., et al. (2004). Physical aggression during early childhood: Trajectories and predictors. Pediatrics, 114(1), e43–e50.

Vitaro, F., Brendgen, M., & Barker, E. D. (2006). Subtypes of aggressive behaviors: A developmental perspective. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30(1), 12–19.

Webster-Stratton, C., Reid, M. J., & Hammond, M. (2004). Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: Intervention outcomes for parent, child, and teacher training. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33(1), 105–124.

Weissberg, R. P., Kumpfer, K. L., & Seligman, M. E. (2003). Prevention that works for children and youth: An introduction. American Psychological Association, 58(6–7), 425.

Funding

Support for RYDS and RIGS has been provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA020195, R01DA005512), the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (86-JN-CX-0007, 96-MU-FX-0014, 2004-MU-FX-0062), the National Science Foundation (SBR-9123299), and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH56486, R01MH63386). Technical assistance for RYDS/RIGS was provided by an NICHD grant (R24HD044943) to The Center for Social and Demographic Analysis at the University at Albany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of any of the funding agencies.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 15 kb)

Appendices

Appendix A. Individual Items in CBCL Subscales

CBCL Anxiety/Depressive Symptom Subscale Items | |

During the past six months, how is it true that [child]… | |

1. Complains of loneliness? | |

2. Cries a lot? | |

3. Fears (he/she) might think or do something bad? | |

4. Feels (he/she) has to be perfect? | |

5. Feels or complains that no one loves (him/her)? | |

6. Feels others are out to get (him/her)? | |

7. Feels worthless or inferior? | |

8. Is nervous, high-strung, or tense? | |

9. Is too fearful or anxious? | |

10. Feels too guilty? | |

11. Is self-conscious or easily embarrassed? | |

12. Is suspicious? | |

13. Is unhappy, sad, or depressed? | |

14. Worries? | |

CBCL Aggression Subscale Items | |

During the past six months, how is it true that [child]… | |

1. Argues a lot? | |

2. Brags or boasts? | |

3. 17Is cruel, bullying, or mean to others? | |

4. Demands a lot of attention? | |

5. Destroys (his/her) own things? | |

6. Destroys things belonging to (his/her) family or others? | |

7. Is disobedient at home? | |

8. Is disobedient at school? | |

9. Is easily jealous? | |

10. Gets into many fights? | |

11. Physically attacks people? | |

12. Screams a lot? | |

13. Clowns or shows off? | |

14. Is stubborn, sullen, or irritable? | |

15. Has sudden changes in (his/her) mood or feelings? | |

16. Talks too much? | |

17. Teases a lot? | |

18. Has temper tantrums or a hot temper? | |

19. Threatens people? | |

20. Is unusually loud? |

Appendix B. Trajectory Model Diagnostics

Panel A. Anxiety/Depressive Symptoms | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

95% CI | ||||||

Group | \( \hat{\pi} \) | lower | upper | \( \hat{p} \) | Ave PP | Odds CC |

Low | 0.545 | 0.486 | 0.604 | 0.551 | 0.967 | 24.7 |

Moderate | 0.331 | 0.275 | 0.387 | 0.326 | 0.952 | 40.2 |

High | 0.124 | 0.088 | 0.160 | 0.123 | 0.986 | 503.4 |

Panel B. Aggression Trajectories | ||||||

95% CI | ||||||

Group | \( \hat{\pi} \) | lower | upper | \( \hat{p} \) | Ave PP | Odds CC |

Low | 0.428 | 0.359 | 0.497 | 0.434 | 0.955 | 28.1 |

Moderate | 0.408 | 0.347 | 0.469 | 0.404 | 0.934 | 20.4 |

High | 0.164 | 0.106 | 0.222 | 0.162 | 0.942 | 82.9 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Augustyn, M.B., Loughran, T., Philippi, P.L. et al. How Early Is Too Early? Identification of Elevated, Persistent Problem Behavior in Childhood. Prev Sci 21, 445–455 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-019-01060-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-019-01060-y