Abstract

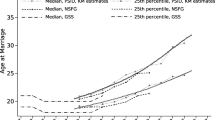

Most studies of union formation focus on short-term probabilities of marrying, cohabiting, or divorcing in the next year. In this study, we take a long-term perspective by considering joint probabilities of marrying or cohabiting by certain ages and maintaining the unions for at least 8, 12, or even 24 years. We use data for female respondents in the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth to estimate choice models for multiple stages of the union-forming process. We then use the estimated parameters to simulate each woman’s sequence of union transitions from ages 18–46, and use the simulated outcomes to predict probabilities that women with given characteristics follow a variety of long-term paths. We find that a typical, 18 year-old woman with no prior unions has a 22 % chance of cohabiting or marrying within 4 years and maintaining the union for 12+ years; this predicted probability remains steady until the woman nears age 30, when it falls to 17 %. We also find that unions entered via cohabitation contribute significantly to the likelihood of experiencing a long-term union, and that this contribution grows with age and (with age held constant) as women move from first to second unions. This finding reflects the fact that the high probability of entering a cohabiting union more than offsets the relatively low probability of maintaining it for the long-term. Third, the likelihood of forming a union and maintaining it for the long-term is highly sensitive to race, but is largely invariant to factors that can be manipulated by public policy such as divorce laws, welfare benefits, and income tax laws.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As we detail in the “Data” section, our sample consists of a narrow birth cohort of women born in 1960–1964, all of whom are followed from age 18 into their mid 40s. As a result, age effects cannot be distinguished from time period effects.

While single-stage analyses are the norm, some authors consider two different stages—e.g., Bitler et al. (2004) identify effects of welfare policy on both marriage and divorce probabilities, while Martin and Bumpass (1989) and Teachman (1986) model marriage-to-divorce transitions separately for first and second marriages.

In these illustrations, continuous marriage and/or cohabitation sequences (MMM, CCC, CCM, etc.) refer to ongoing unions with the same partner. We use event history data and partner identifiers to distinguish continuous unions with 1 partner from multiple unions in our data.

In our sample, the mean-age at first union formation is just under 24, and the mean-age at first marital dissolution is 30.

We describe the covariates in “Covariates” section. The only time-varying variables that are not based on event history data are county- and state-specific environmental variables. Residential location in some years is only known at the time of each interview, so we assume residential changes take place half-way between successive interview dates.

A potential shortcoming of the NLSY79 is that from 1970 to 1989 (when respondents in our sample were ages 25–29), only cohabitations that spanned the interview date were identified. This caused the shortest cohabitation spells to be under-sampled, and could affect our inferences if “true” first spells are systematically and substantially shorter than first spells that span interview dates. To assess this problem, we use the 1997 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth—which tracks all cohabitation spells in an event history format—to identify cohabitation spells from age 18 to 25-29; i.e., we follow respondents, all of whom were born in 1980–1984, from their 18th birthday to the 2009 interview date. Of the 8,426 cohabitation spells observed for 8,115 respondents, only 14 % would be “lost” if we required them to be in-progress at an interview date. Among respondents with more than one spell, only 4.4 % have a “lost” spell that is shorter than the second spell. Extrapolating to the NLSY79, it appears unlikely that we significantly over-predict the duration of cohabitation spells simply because a small number of spells that do not span interview are unobserved.

Lillard and Waite (1993) and Steel et al. (2005) jointly estimate union formation/dissolution and childbearing, although they do not simulate outcomes across multiple stages. Simply adding covariates for childbearing to our model would be inappropriate because these measures are endogenous to union-related decisions.

Lundberg (2010) argues that noncognitive skills directly affect marital surplus if, for example, couples with similar personality traits receive enhanced gains from consumption complementarities, or if couples with dissimilar noncognitive (and cognitive) skills receive greater gains from production complementarities. A formal test of these hypotheses is beyond the scope of our study, but a general conclusion to be drawn is that any factor that potentially affects the gains to marriage is a viable candidate for inclusion among our covariates.

Our exogeneity claim relies on the assumption that women do not choose their state of residence in conjunction with their marital status to lower divorce costs, reduce income taxes, or increase welfare benefits. Short of modeling migration decisions, the only alternative to assuming state of residence is exogenous to include state fixed effects in our models. We opt not to use this identification strategy because within-state variation in each factor is fairly systematic: over time, divorce laws move toward “no fault,” tax law becomes more marriage neutral, and welfare-related costs of marriage are reduced. Because we cannot separate the effects of these temporal trends from aging effects—and because most of the variation in each factor is between states—we prefer to rely on cross-state variation in our data.

To clarify the interpretation of these estimates, 28.0 % of simulated paths from age 18 to 22 have the form SM*, SSM*, SSSM*, or SSSSM*, where the asterisk represents the fact that simulated outcomes beyond the initial single-to-married transition are irrelevant for this computation. Similarly, 16.5 % have simulated paths of the type SC*, SSC*, SSSC*, or SSSSC*.

These findings—and all findings reported in this study—are based on women’s observed transitions between being single, cohabitation, and marriage. We are unable to predict how the probabilities would change if women were denied their chosen outcome—e.g., if women who are observed choosing cohabitation had been forced to either marry or remain single.

The sole exception is that black women lag the column A sample by only 1.6 percentage points in their conditional probability of maintaining a union formed via marriage (row a′).

One concern is that we estimate trivial effects of “pro-marriage” factors because divorce laws and income tax bonuses only affect high income women, while AFDC/TANF payments only affect low income women. To explore this, we allowed the coefficients for each variable in this group to differ for high and low income women using multiple definitions of high and low (expected) income, and we allowed each policy variable to have varying effects in isolation and in combination with other interactions. For each alternative specification, we failed to reject the null hypothesis that the coefficients are equal for alternative income groups. Our findings were also unchanged when we experimented with alternative measures of divorce laws and income tax marriage penalties/bonuses.

Using alternative starting ages (not reported), we find that the predicted probabilities do not begin declining until women are very close to age 30.

References

Alm, J., & Whittington, L. A. (1999). For love or money? The impact of income taxes on marriage. Economica, 66, 297–316.

Almlund, M., Duckworth, A. L., Heckman, J., & Kautz, T. (2011). Personality, psychology, and economics. In E. A. Hanushek, S. Machin, & L. Woessmann (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of education (Vol. 4). Amsterdam: Elsevier B.V.

Amato, P. R. (2000). The consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1269–1287.

Axinn, W. G., & Thornton, A. (1992). The relationship between cohabitation and divorce: Selectivity or causal influence? Demography, 29, 357–374.

Bennett, N. G., Bloom, D. E., & Craig, P. H. (1989). The divergence of black and white marriage patterns. American Journal of Sociology, 95, 692–722.

Bitler, M. P., Gelbach, J. B., Hoynes, H. W., & Zavodny, M. (2004). The impact of welfare reform on marriage and divorce. Demography, 41, 213–236.

Blackburn, M. L. (2000). Welfare effects on the marital decisions of never-married mothers. Journal of Human Resources, 35, 116–142.

Blau, D. M., & van der Klaauw, W. (2013). What determines family structure? Economic Inquiry, 51, 579–604.

Bowles, S., Gintis, H., & Osborne, M. (2001). The determinants of earnings: A behavioral approach. Journal of Economic Literature, 38, 1137–1176.

Bramlett, M. D., & Mosher, W. D. (2002). Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and remarriage in the United States. Vital and Health Statistics, 23(22), 1–93.

Brien, M. J., Lillard, L. A., & Stern, S. (2006). Cohabitation, marriage, and divorce in a model of match quality. International Economic Review, 47, 451–494.

Bumpass, L. L., & Lu, H.-H. (2000). Trends in cohabitation and implications for children’s family contexts in the United States. Population Studies, 54, 29–41.

Bumpass, L. L., Sweet, J. A., & Cherlin, A. (1991). The role of cohabitation in declining rates of marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53, 913–927.

Burgess, S., Propper, C., & Aassve, A. (2003). The role of income in marriage and divorce transitions among young Americans. Journal of Population Economics, 16, 455–475.

Clarkberg, M., Stolzenberg, R. M., & Waite, L. J. (1995). Attitudes, values and entrance into cohabitational versus marital unions. Social Forces, 74, 609–632.

Duncan, G. J., & Hoffman, S. D. (1985). Economic consequences of marital instability. In M. David & T. Smeeding (Eds.), Horizontal equity, uncertainty, and well-being (pp. 427–470). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fomby, P., & Cherlin, A. J. (2007). Family instability and child well-being. American Sociological Review, 72, 181–204.

Friedberg, L. (1998). Did unilateral divorce raise divorce rates? Evidence from panel data. American Economic Review, 88, 608–627.

Grogger, J., & Bronars, S. G. (2001). The effect of welfare payments on the marriage and fertility behavior of unwed mothers: Results from a twins experiment. Journal of Political Economy, 109, 529–545.

Guzzo, K. B. (2009). Marital intentions and the stability of first cohabitations. Journal of Family Issues, 30, 179–205.

Iyvarakul, T., McElroy, M. B., & Staub, K. (2011). Dynamic optimization in models for state panel data: A cohort panel data of the effects of divorce laws on divorce rates. Unpublished manuscript, March 2011.

Jose, A., Daniel O’Leary, K., & Moyer, A. (2010). Does premarital cohabitation predict subsequent marital stability and marital quality? A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 106–116.

Kamp Dush, C. M., Cohan, C. L., & Amato, P. R. (2003). The relationship between cohabitation and marital quality and stability: Change across cohorts? Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 539–549.

Keane, M. P., & Wolpin, K. I. (2010). The role of labor and marriage markets, preference heterogeneity and the welfare system in the life cycle decisions of white, black, and Hispanic women. International Economic Review, 41, 851–892.

Korenman, S., & Neumark, D. (1991). Does marriage really make men more productive? Journal of Human Resources, 26, 282–307.

Lehrer, E. L., & Chiswick, C. (1993). Religion as a determinant of marital stability. Demography, 30, 385–404.

Lichter, D. T., LeClere, F. B., & McLaughlin, D. K. (1991). Local marriage markets and the marital behavior of black and white women. American Journal of Sociology, 96, 843–867.

Lichter, D. T., McLaughlin, D. K., & Ribar, D. C. (2002). Economic restructuring and the retreat from marriage. Social Science Review, 31, 230–256.

Lichter, D. T., Qian, Z., & Mellott, L. M. (2006). Union transitions among poor cohabiting women. Demography, 43, 223–240.

Light, A., & Ahn, T. (2010). Divorce as risky behavior. Demography, 46, 895–921.

Light, A., & Omori, Y. (2008). Economic incentives and family formation. Ohio State University working paper.

Light, A., & Omori, Y. (2012). Can long-term cohabiting and marital unions be incentivized? Research in Labor Economics, 36, 241–283.

Lillard, L. A., & Waite, L. J. (1993). A joint model of marital childbearing and marital disruption. Demography, 30, 653–681.

Lillard, L. A., Brien, M. J., & Waite, L. J. (1995). Premarital cohabitation and subsequent marital dissolution: A matter of self-selection? Demography, 32, 437–457.

Lundberg, S. (2010). Personality and marital surplus. IZA Discussion Paper 4945.

Manning, W. D., & Cohen, J. A. (2012). Premarital cohabitation and marital dissolution: An examination of recent marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 377–387.

Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (1995). Why marry? Race and the transition to marriage among cohabitors. Demography, 32, 509–520.

Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (2002). First comes cohabitation and then comes marriage? Journal of Family Issues, 23s, 1065–1087.

Martin, T. C., & Bumpass, L. L. (1989). Recent trends in marital disruption. Demography, 26, 37–51.

Oppenheimer, V. K. (2000). The role of economic factors in union formation. In L. J. Waite, et al. (Eds.), Ties that bind: Perspectives on marriage and cohabitation. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Osborne, C., & McLanahan, S. (2007). Partnership instability and child well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 1065–1083.

Osborne, C., Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (2007). Married and cohabiting parents’ relationship stability: A focus on race and ethnicity. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 69, 1345–1366.

Peters, H. E. (1986). Marriage and divorce: Informational constraints and private contracting. American Economic Review, 76, 437–454.

Phillips, J. A., & Sweeney, M. M. (2005). Premarital cohabitation and marital disruption among white, black, and Mexican-American Women. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 67, 296–314.

Reinhold, S. (2010). The link between premarital cohabitation and marital instability. Demography, 47, 719–734.

Smock, P. J., & Manning, W. D. (1997). Cohabiting partners’ economic circumstances and marriage. Demography, 34, 331–341.

Stanley, S. M., Rhoades, G. K., Amato, P. R., Markman, H. J., & Johnson, C. A. (2010). The timing of cohabitation and engagement: Impact on first and second marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 906–918.

Steel, F., Kallis, C., Goldstein, H., & Joshi, H. (2005). The relationship between childbearing and transitions from marriage and cohabitation in Britain. Demography, 42, 647–673.

Stratton, L. S. (2002). Examining the wage differential for married and cohabiting men. Economic Inquiry, 40, 199–212.

Svarer, M. (2004). Is your love in vain? Another look at premarital cohabitation and divorce. Journal of Human Resources, 39, 523–535.

Teachman, J. D. (1986). First and second marital dissolution: A decomposition exercise for whites and blacks. Sociological Quarterly, 27, 571–590.

Teachman, J. D. (2008). Complex life course patterns and the risk of divorce in second marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 294–305.

Thornton, A., Axinn, W. G., & Hill, D. H. (1992). Reciprocal effects of religiosity, cohabitation and marriage. American Journal of Sociology, 98, 628–651.

van der Klaauw, W. (1996). Female labour supply and marital status decisions: A life-cycle model. Review of Economic Studies, 63, 199–235.

Whittington, L. A., & Alm, J. (1997). Til death or taxes do us part: The effect of income taxation on divorce. Journal of Human Resources, 32, 388–412.

Wolfers, J. (2006). Did unilateral divorce raise divorce rates? A reconciliation and new results. American Economic Review, 96, 1802–1820.

Wu, Z., & Pollard, M. S. (2000). Economic circumstances and the stability of nonmarital cohabitation. Journal of Family Issues, 21, 303–328.

Xie, Y., Raymo, J. M., Goyette, K., & Thornton, A. (2003). Economic potential and entry into marriage and cohabitation. Demography, 40, 351–368.

Yelowitz, A. S. (1998). Will extending medicaid to two-parent families encourage marriage? Journal of Human Resources, 33, 833–865.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a Grant to Light from the National Science Foundation (Grant SES-0415427) and a Grant to Omori from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C)25380356); we thank both agencies for their generous support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Construction of Environmental Covariates

Divorce Variables

Using the state of residence and calendar year corresponding to each person–year observation, we characterize the prevailing divorce law using a five-way classification scheme. “Unilateral divorce, no separation, no fault property settlement” means the woman can obtain a unilateral divorce without a mandatory separation period, and she can obtain a property settlement (as well as the divorce) without having to establish fault (marital misconduct). “Unilateral divorce, no separation, fault for property settles” refers to a more restrictive environment in which unilateral, no fault, no mandatory separation divorce is granted, but fault must be established for the court to make a property settlement. “Unilateral, separation, no fault property settlement” and “unilateral, separation, fault for property settlement” are defined similarly, but in both categories unilateral, no fault divorce is granted only after a mandatory separation requirement is met. The omitted group identifies state-year observations where divorce is granted only with bilateral consent. This five-way taxonomy is ordered in the sense that bilateral divorce (the omitted group) limits the right to divorce relative to unilateral divorce with a separation requirement which, in turn, is more restrictive than unilateral divorce without a separation requirement. Similarly, the need to establish fault raises the cost of divorce relative to no fault property settlements. Individual women may encounter exceptions to these general restrictions depending on whether they invoke community property laws, seek alimony or child custody agreements, and/or have a prenuptial agreement. We do not define our covariates on the basis of these individual characteristics because they may be endogenous to union-related outcomes.

We construct our divorce variables using information in Friedberg (1998) supplemented by data available at www.abanet.org.

AFDC/TANF Benefits

We assign the state- and year-specific maximum, monthly AFDC or TANF benefit available to a family of four, divided by the implicit price deflator for gross domestic product. These variables are independent of each woman’s income, family status, and other determinants of her AFDC/TANF eligibility status, all of which are likely to be endogenous to union formation.

These values are taken from the welfare benefit database ben_dat.txt available at http://www.econ.jhu.edu/People/Moffitt/datasets.html and the Urban Institute’s welfare rules database available at http://www.urban.org/toolkit/databases/index.cfm.

State Income Tax Marriage Penalty

To construct this variable, our first step is to use 1979–2008 NLSY79 data for all male and female respondents who are age 18 or older to estimate earnings models for eight separate samples defined by marital status (single, cohabiting, married, or separated/divorced) and sex. We use individuals’ total earnings for the prior year as the dependent variable. Regressors are the year-specific implicit price deflator for personal consumption expenditure; county- and year-specific per capita income; the county- and year-specific unemployment rate; a quartic in age; age-adjusted AFQT scores; dummy variables indicating the current highest grade completed is 0–11, 12, 13–15, or 16+; and indicators for whether the respondent is black or Hispanic. Our second step is to use the eight sets of estimated parameters to compute year-specific, race/ethnicity-specific, sex-specific, marital status-specific predicted incomes, which we use to identify the median predicted income for each sample. In step 3, we associate each person–year observation in our stage 1–5 samples with the median predicted incomes for both men and women in the same stage (single, cohabiting, married, or separated/divorced), in the same year, and with the same race/ethnicity as the respondent. Our final step is to use Taxsim (available at http://www.nber.org/taxsim/) to compute the state income tax liability for the median man and median woman, first assuming they are married and filing jointly, and then assuming they are single or cohabiting and filing separately.

The difference between the state income tax liability if married and the tax liability if single or cohabiting is the variable used in our state-specific choice models. This variable identifies the expected income tax penalty (or bonus) associated with marriage for a median woman who shares the sample member’s race/ethnicity, marital status, and state of residence, and who has a (potential) partner with the same race/ethnicity and marital status. Our measure is correlated with tax obligations based on actual income, but within-stage variation is entirely dependent on cross-year and cross-state variation in income tax laws. We rely on state income tax laws rather than federal income tax laws because the latter only varies across years, and is difficult to separate from aging effects.

Appendix 2

See Table 9.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Light, A., Omori, Y. Determinants of Long-Term Unions: Who Survives the “Seven Year Itch”?. Popul Res Policy Rev 32, 851–891 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-013-9285-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-013-9285-6