When men are ambitious, it’s just taken for granted. Well of course they should be ambitious. When women are ambitious, why?

—Barack Obama

(Interview with Samantha Bee, Full Frontal with Samantha Bee, 31 October 2016).

Abstract

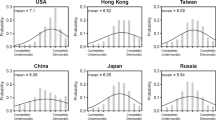

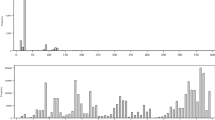

Are ambitious women punished in politics? Building on literature from negotiation, we argue that women candidates who are perceived to be ambitious are more likely to face social backlash. We first explore what the term ‘ambitious’ means to voters, developing and testing a new multidimensional concept of perceived ambition, from desire to run for higher office to scope of agenda. We then test the link between these ‘ambitious’ traits and voter support for candidates using five conjoint experiments in two countries, the U.S. and the U.K. Our results show that while ambitious women are not penalized overall, the aggregate results hide differences in taste for ambitious women across parties. We find that in the U.S. left-wing voters are more likely to support women with progressive ambition than right-wing voters (difference of 7% points), while in the U.K. parties are not as divided. Our results suggest that ambitious women candidates in the U.S. face bias particularly in the context of non-partisan races (like primaries and local elections), when voters cannot rely on party labels to make decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Shear (2016).

McCormack (2008).

Roberts (2018).

Denvir (2018).

Ocasio-Cortez, Alexandria. @Ocasio2018. Tweet. 30 June 2018, 9:08 AM.

Amann and Becker (2017).

Mascaro (2017).

Replication materials are available in the Political Behavior Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KVTPVX.

Least Ambitious results available from author. We can only look at four attribute combinations at a time in the FindIt package for R; however, additional analysis where we substitute Parental and Experience-based Ambition for other traits confirms the findings presented here.

We note that the agenda-based trait “Complete overhaul” of the political agenda is also associated with a significant and positive bump, but it is smaller at 0.75.

For DLABSS 1, marginal means for Democrats and Republicans for women with progressive ambition are 0.56 and 0.42 (\(\hbox{p} < 0.001\)), and for DLABBS 2, 0.54 and 0.46 (\(\hbox{p} = 0.02\)).

See Replication Files.

References

Abney, R. M., & Peterson, R. D. (2011). Glass ceiling or glass elevator: Are voters biased in favor of women candidates in California elections? The California Journal of Politics and Policy, 3(1), 1–26.

Allen, P., & Cutts, D. (2017). Aspirant candidate behaviour and progressive political ambition. Research & Politics, 4(1), 2053168017691444.

Amann, M., & Becker, S. (2017). How far to the right is Alice Weidel? Spiegel Online, 4 May 2017.

Andersen, D. J., & Ditonto, T. (2018). Information and its presentation: Treatment effects in low-information vs. high-information experiments. Political Analysis, 26(4), 379–398.

Anzia, S. F., & Bernhard, R. (2019). How does gender stereotyping affect women at the ballot box? Evidence from local elections in California, 1995–2016. Working Paper.

Barr, R. R. (2009). Populists, outsiders and anti-establishment politics. Party Politics, 15(1), 29–48.

Bauer, N. M. (2017). The effects of counterstereotypic gender strategies on candidate evaluations. Political Psychology, 38(2), 279–295.

Bertrand, M., Kamenica, E., & Pan, J. (2015). Gender identity and relative income within households. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(2), 571–614.

Black, J. H., & Erickson, L. (2000). Similarity, compensation, or difference? Women & Politics, 21(4), 1–38.

Bongiorno, R., Bain, P. G., & David, B. (2014). If you’re going to be a leader, at least act like it! Prejudice towards women who are tentative in leader roles. British Journal of Social Psychology, 53(2), 217–234.

Bowles, H. R., & Babcock, L. (2013). How can women escape the compensation negotiation dilemma? Relational accounts are one answer. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(1), 80–96.

Bowles, H. R., Babcock, L., & Lai, L. (2007). Social incentives for gender differences in the propensity to initiate negotiations: Sometimes it does hurt to ask. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 103(1), 84–103.

Brians, C. L. (2005). Women for women? Gender and party bias in voting for female candidates. American Politics Research, 33(3), 357–375.

Bucchianeri, P. (2018). Is running enough? Reconsidering the conventional wisdom about women candidates. Political Behavior, 40(2), 435–466.

Burrell, B. (1992). Women candidates in open-seat primaries for the US house: 1968–1990. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 17(4), 493–508.

Bursztyn, L., Fujiwara, T., & Pallais, A. (2017). ‘Acting wife’: Marriage market incentives and labor market investments. American Economic Review, 107(11), 3288–3319.

Campbell, R., & Childs, S. (2014). Parents in parliament: ‘Where’s mum? The Political Quarterly, 85(4), 487–492.

Cassese, E. C., & Holman, M. R. (2017). Party and gender stereotypes in campaign attacks. Political Behavior, 40, 785–807.

Chang, L., & Krosnick, J. A. (2009). National surveys via RDD telephone interviewing versus the Internet: Comparing sample representativeness and response quality. Public Opinion Quarterly, 73(4), 641–678.

Clayton, A., Robinson, A. L., Johnson, M. C., & Muriaas, R. (2019). (How) do voters discriminate against women candidates?: Experimental and qualitative evidence from Malawi. Comparative Political Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414019858960.

Costantini, E. (1990). Political women and political ambition: Closing the gender gap. American Journal of Political Science, 34(3), 741–770.

Crowder-Meyer, M. (2018). Baker, bus driver, babysitter, candidate? Revealing the gendered development of political ambition among ordinary Americans. Political Behavior, 42, 359–384.

Crowder-Meyer, M., & Cooperman, R. (2018). Can’t buy them love: How party culture among donors contributes to the party gap in women’s representation. The Journal of Politics, 80(4), 000–000.

Crowder-Meyer, M., Gadarian, S. K., & Trounstine, J. (2015). Electoral institutions, gender stereotypes, and women’s local representation. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 3(2), 318–334.

Darcy, R., & Schramm, S. S. (1977). When women run against men. Public Opinion Quarterly, 41(1), 1–12.

Denvir, D. (2018). Bernie Sanders: Bold politics is good politics Jacobin, 16 July 2018.

Ditonto, T. (2017). A high bar or a double standard? Gender, competence, and information in political campaigns. Political Behavior, 39(2), 301–325.

Ditto, P. H., & Mastronarde, A. J. (2009). The paradox of the political maverick. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(1), 295–298.

Dolan, K. (2004). The impact of candidate sex on evaluations of candidates for the US House of Representatives. Social Science Quarterly, 85(1), 206–217.

Dolan, K. (2008). Is there a ‘gender affinity effect’ in American politics? Information, affect, and candidate sex in US House elections. Political Research Quarterly, 61(1), 79–89.

Dolan, K. A. (2014). When does gender matter? Women candidates and gender stereotypes in American Elections. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Donnelly, K., Twenge, J. M., Clark, M. A., Shaikh, S. K., Beiler-May, A., & Carter, N. T. (2016). Attitudes toward women’s work and family roles in the United States, 1976–2013. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(1), 41–54.

Druckman, J. N., & Kam, C. D. (2011). Students as experimental participants. In Cambridge handbook of experimental political science (Vol. 1, pp. 41–57). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dynes, A. M., Hassell, H. J. G., & Miles, M. R. (2019). The personality of the politically ambitious. Political Behavior, 41(2), 309–336.

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573.

Eagly, A. H., Nater, C., Miller, D. I., Kaufmann, M., & Sczesny, S. (2019). Gender stereotypes have changed: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of US public opinion polls from 1946 to 2018. American Psychologist, 75(3), 301–315.

Egami, N., & Imai, K. (2018). Causal interaction in factorial experiments: Application to conjoint analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 114(526), 1–34.

Egami, N., Ratkovic, M., & Imai, K. (2015). FindIt: Finding heterogeneous treatment effects. Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=FindIt.

Elder, L., & Greene, S. (2012). The politics of parenthood: Causes and consequences of the politicization and polarization of the American family. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Enos, R. D., Hill, M., Strange, A. M., & Lakeman, A. (2018). Intrinsic motivation at scale: Online volunteer laboratories for social science research. PLoS ONE, 14(8), e022167.

Folke, O., & Rickne, J. (2020). All the single ladies: Job promotions and the durability of marriage. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 12(1), 260–87.

Fox, R., & Lawless, J. (2011a). Barefoot and pregnant, or ready to be president? gender, family roles, and political ambition in the 21st century. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1901324.

Fox, R. L., & Lawless, J. L. (2004). Entering the arena? Gender and the decision to run for office. American Journal of Political Science, 48(2), 264–280.

Fox, R. L., & Lawless, J. L. (2005). To run or not to run for office: Explaining nascent political ambition. American Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 642–659.

Fox, R. L., & Lawless, J. L. (2010). If only they’d ask: Gender, recruitment, and political ambition. The Journal of Politics, 72(02), 310–326.

Fox, R. L., & Lawless, J. L. (2011b). Gendered perceptions and political candidacies: A central barrier to women’s equality in electoral politics. American Journal of Political Science, 55(1), 59–73.

Fox, R. L., & Lawless, J. L. (2014). Uncovering the origins of the gender gap in political ambition. American Political Science Review, 108(3), 499–519.

Fulton, S. A. (2012). Running backwards and in high heels: The gendered quality gap and incumbent electoral success. Political Research Quarterly, 65(2), 303–314.

Fulton, S. A., Maestas, C. D., Maisel, L. S., & Stone, W. J. (2006). The sense of a woman: Gender, ambition, and the decision to run for congress. Political Research Quarterly, 59(2), 235–248.

Gaddie, R. K., & Bullock, C. S. (1997). Structural and elite features in open seat and special US House elections: Is there a sexual bias? Political Research Quarterly, 50(2), 459–468.

Hainmueller, J., Hangartner, D., & Yamamoto, T. (2015). Validating vignette and conjoint survey experiments against real-world behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(8), 2395–2400.

Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J., & Yamamoto, T. (2013). Causal inference in conjoint analysis: Understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Political Analysis, 22(1), 1–30.

Hayes, D. (2011). When gender and party collide: Stereotyping in candidate trait attribution. Politics & Gender, 7(2), 133–165.

Hekman, D. R., Johnson, S. K., Foo, M.-D., & Yang, W. (2017). Does diversity-valuing behavior result in diminished performance ratings for non-white and female leaders? Academy of Management Journal, 60(2), 771–797.

Herrick, R., & Moore, M. K. (1993). Political ambition’s effect on legislative behavior: Schlesinger’s typology reconsidered and revisited. The Journal of Politics, 55(3), 765–776.

Hibbing, J. R. (1986). Ambition in the House: Behavioral consequences of higher office goals among US representatives. American Journal of Political Science, 30, 651–665.

Hochschild, A., & Machung, A. (2012). The second shift: Working families and the revolution at home. New York: Penguin.

Inter-Parliamentary Union. (2019). Gender equality at a glance. https://www.ipu.org/resources/publications/about-ipu/2019-03/gender-equality-glance

Jenson, J. (2018). Extending the boundaries of citizenship: Women’s movements of Western Europe. In A. Basu (Ed.), The challenge of local feminisms (pp. 405–434). London: Routledge.

Kanthak, K., & Woon, J. (2015). Women don’t run? Election aversion and candidate entry. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 595–612.

Keith, D. J., & Verge, T. (2016). Nonmainstream left parties and women’s representation in Western Europe. Party Politics, 39(2), 351–379.

Kirkland, P. A., & Coppock, A. (2017). Candidate choice without party labels. Political Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-017-9414-8

Koenig, A. M., Eagly, A. H., Mitchell, A. A., & Ristikari, T. (2011). Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms. Psychological Bulletin, 137(4), 616.

Köttig, M., Bitzan, R., & Petö, A. (2017). Gender and far right politics in Europe. Cham: Springer.

Laustsen, L. (2017). Choosing the right candidate: Observational and experimental evidence that conservatives and liberals prefer powerful and warm candidate personalities, respectively. Political Behavior, 39(4), 883–908.

Lauterbach, K. E., & Weiner, B. J. (1996). Dynamics of upward influence: How male and female managers get their way. The Leadership Quarterly, 7(1), 87–107.

Lawless, J. L., & Fox, R. L. (2005). It takes a candidate: Why women don’t run for office. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lawless, J. L., & Pearson, K. (2008). The primary reason for women’s underrepresentation? Reevaluating the conventional wisdom. The Journal of Politics, 70(01), 67–82.

Leeper, T. J., Hobolt, S. B., & Tilley, J. (2020). Measuring subgroup preferences in conjoint experiments. Political Analysis, 28(2), 207–221.

Maestas, C. (2000). Professional legislatures and ambitious politicians: Policy responsiveness of state institutions. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 25, 663–690.

Maestas, C. D., Fulton, S., Maisel, L. S., & Stone, W. J. (2006). When to risk it? Institutions, ambitions, and the decision to run for the US House. American Political Science Review, 100(2), 195–208.

Mascaro, L. (2017). Congress opens with an ambitious agenda for the Trump era. Los Angeles Times, 3 January 2017.

Matson, M., & Fine, T. S. (2006). Gender, ethnicity, and ballot information: Ballot cues in low-information elections. State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 6(1), 49–72.

Mazei, J., Hüffmeier, J., Freund, P. A., Stuhlmacher, A. F., Bilke, L., & Hertel, G. (2015). A meta-analysis on gender differences in negotiation outcomes and their moderators. Psychological Bulletin, 141(1), 85.

McCormack, J. (2008). Rasmussen: Palin More Popular Than Obama and McCain. The Weekly Standard, 5 September 2008.

Meret, S. (2015). Charismatic female leadership and gender: Pia Kjærsgaard and the Danish People’s Party. Patterns of Prejudice, 49(1–2), 81–102.

Mo, C. H. (2015). The consequences of explicit and implicit gender attitudes and candidate quality in the calculations of voters. Political Behavior, 37(2), 357–395.

Norris, P. (1985). Women’s legislative participation in Western Europe. West European Politics, 8(4), 90–101.

O’Brien, D. Z. (2015). Rising to the top: Gender, political performance, and party leadership in parliamentary democracies. American Journal of Political Science, 59(4), 1022–1039.

O’Brien, D. Z. (2018). Righting’ conventional wisdom: Women and right parties in established democracies. Politics & Gender, 14(1), 27–55.

O’Brien, D. Z., & Rickne, J. (2016). Gender quotas and women’s political leadership. American Political Science Review, 110(01), 112–126.

Okimoto, T. G., & Brescoll, V. L. (2010). The price of power: Power seeking and backlash against female politicians. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(7), 923–936.

Ono, Y., & Burden, B. C. (2019). The contingent effects of candidate sex on voter choice. Political Behavior, 41(3), 583–607.

Paxton, P., Hughes, M. M., & Painter, M. A. (2010). Growth in women’s political representation: A longitudinal exploration of democracy, electoral system and gender quotas. European Journal of Political Research, 49(1), 25–52.

Pearson, K., & McGhee, E. (2004). Strategic differences: The gender dynamics of Congressional candidacies, 1982–2002. In Annual meeting of the midwest political science association conference. http://citation.allacademic.com/meta/p_mla_apa_research_citation/0/6/0/7/2/pages60725/p60725-1.php.

Pearson, K., & McGhee, E. (2013). What it takes to win: Questioning “gender neutral” in US House elections. Politics & Gender, 9(4), 439–462.

Piscopo, J. M. (2018). The limits of leaning in: Ambition, recruitment, and candidate training in comparative perspective. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 7(4), 817–828.

Preece, J. R., Stoddard, O. B., & Fisher, R. (2016). Run, Jane, run! Gendered responses to political party recruitment. Political Behavior, 38(3), 561–577.

Pulichino, M., & Coughlin, J. F. (2005). Introducing transit preferential treatment: Is a political maverick necessary for public transportation to innovate? Journal of Urban Planning and Development, 131(2), 79–86.

Quaranta, M., & Sani, G. M. D. (2018). Left behind? Gender gaps in political engagement over the life course in twenty-seven European countries. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 25(2), 254–286.

Roberts, G., & Tacopino, J. (2018). Ocasio-Cortez wants to be president, mom says. New York Post, 27 June 2018.

Rohde, D. W. (1979). Risk-bearing and progressive ambition: The case of members of the United States House of Representatives. American Journal of Political Science, 23(1), 1–26.

Rudman, L. A., & Goodwin, S. A. (2004). Gender differences in automatic in-group bias: Why do women like women more than men like men? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(4), 494.

Samuels, D. (2003). Ambition, federalism, and legislative politics in Brazil. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2002). Gender stereotypes and vote choice. American Journal of Political Science, 46(1), 20–34.

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2004). Democrats, Republicans, and the politics of women’s place. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Schlesinger, Joseph A. (1966). Ambition and politics: Political careers in the United States. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Schneider, M. C., Holman, M. R., Diekman, A. B., & McAndrew, T. (2016). Power, conflict, and community: How gendered views of political power influence women’s political ambition. Political Psychology, 37(4), 515–531.

Schwarz, S., Hunt, W., & Coppock, A. (2018). What have we learned about gender from candidate choice experiments? A meta-analysis of 30 factorial survey experiments. Unpublished Manuscript. https://alexandercoppock.com/papers/SHC_gender.pdf.

Shames, S. L. (2017). Out of the running: Why millennials reject political careers and why it matters. New York: NYU Press.

Shear, M. (2016). Colin Powell, in Hacked emails, shows scorn for Trump and irritation at Clinton.” The New York Times, 14 September 2016.

Sieberer, U., & Müller, W. C. (2017). Aiming higher: The consequences of progressive ambition among MPs in European parliaments. European Political Science Review, 9(1), 27–50.

Squire, P. (1988). Member career opportunities and the internal organization of legislatures. The Journal of Politics, 50(3), 726–744.

Teele, D. L., Kalla, J., & Rosenbluth, F. (2018). The ties that double bind: Social roles and women’s underrepresentation in politics. American Political Science Review, 112(3), 525–541.

Thomsen, D. (2019). Which women win? Partisan changes in victory patterns in US House Elections. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 412–428.

Tinsley, C. H., Cheldelin, S. I., Schneider, A. K., & Amanatullah, E. T. (2009). Women at the bargaining table: Pitfalls and prospects. Negotiation Journal, 25(2), 233–248.

Treul, S. A. (2009). Ambition and party loyalty in the US Senate. American Politics Research, 37(3), 449–464.

Williams, M. J., & Tiedens, L. Z. (2016). The subtle suspension of backlash: A meta-analysis of penalties for women’s implicit and explicit dominance behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 142(2), 165.

Wodak, R. (2015). The politics of fear: What right-wing populist discourses mean. London: Sage.

Wolbrecht, C. (2010). The politics of women’s rights: Parties, positions, and change. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Acknowledgements

We thank Loes Aaldering, Peter Allen, Renata Bongiorno, Whitney Ross Manzo, Shom Mazumder, Eileen McDonagh, Jennifer Piscopo, Shauna Shames, four anonymous reviewers, and participants at APSA, EPSA, the Exeter SEORG seminar, the Harvard Gender & Politics workshop, and the Harvard American Politics Research Workshop for their valuable comments on earlier versions of this paper. We acknowledge funding for the Harvard Digital Lab for the Social Sciences from The Pershing Square Venture Fund for Research on the Foundations of Human Behavior. We also thank the Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics and APSA for small grants that made this research possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study was approved by the Human Research Ethics committee of Harvard University (Ethics Approval Number: IRB17-1171) and the University of Bath (Ethics Approval Number: S17-027).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Saha, S., Weeks, A.C. Ambitious Women: Gender and Voter Perceptions of Candidate Ambition. Polit Behav 44, 779–805 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09636-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09636-z