Abstract

While political accountability requires that voters can form an accurate picture of government performance, public evaluations of government performance in established democracies are often distorted by partisan considerations. We test whether the same factors bias evaluations of government performance in a new democracy where partisanship is less stable and defined. This analysis estimates individual-level models of retrospective national economic evaluations in South Korea’s 2017 presidential election. South Korea has unstable party politics, low levels of party institutionalization, and high levels of public distrust in political parties. Yet even in this context we find that voters’ economic evaluations are significantly affected by political loyalties such as party identification. This endogeneity is sufficiently large that it results in aggregate consumer evaluations of the economy that systematically vary across regions depending upon the relationship of the president to that region. The findings confirm that party identification shapes citizen opinions even in a context where its effect would likely be weak.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Mattes and Krönke (forthcoming) for a recent exception.

See Online Appendix 1 for a brief history of these party names changes.

The Yeongnam region is the Gyeongsang-do provinces located in the southeastern part of South Korea where former presidents, Park Chung-hee, Chun Doo-hwan, Roh Tae-woo, Kim Young-sam, and Park Guen-hye are from. The Honam region is the Jeolla-do provinces located in the southwestern part of South Korea and is the hometown of former president Kim Dae-jung who was the most prominent democratic dissident before the nation’s democratization.

Although they merely control for whether the respondent is a strong or weak partisan and do not test if government partisans differ in their perceptions from opposition ones.

The raw data are available at https://www.ksdcdb.kr.

“Would you say that during the past Park administration, the state of the economy in South Korea has gotten better, stayed about the same, or gotten worse?” Respondents were asked to choose from “Much better,” “Better,” “Same,” “Worse,” “Much worse.” Higher values represent more favorable evaluations of the national economy.

Party Identification: A question asked which party a respondent feels closest to and respondents were asked to choose from 1 = “Democratic Party,” 2 = “Liberty Korea Party,” 3 = “The People’s Party,” 4 = “Bareun Party,” 5 = “Justice Party,” 6 = “Others.” If the respondent said “Liberty Korea Party” they were coded as a ruling party identifier and if they mentioned any other party as an opposition party supporter.

“Which candidate did you vote for in the 18th presidential election? Park Geun-hye, Moon Jae-in, Others, Did not vote.” Those who were ineligible or who don’t remember their vote are excluded.

The substantive results do not change if we instead include dummy variables for each province.

In results not presented here, we tested for whether the effects of party identification and previous vote choice differ by the extent to which voters are sophisticated—across levels of education, political interest, and media usage. None of these potential interactive relationships that some scholars have suggested exist are operating in South Korea.

In that survey we also found that respondents who had voted for the incumbent were more likely to have positive views of the economy but that effect was limited to partisans, as previous vote did not have a significant association with opinions when partisanship was controlled for.

While one could argue that previous vote choice is temporally prior to the present moment and thus should be an exogenous instrument (which is the approach used by Lewis-Beck et al. 2008), we decided to be conservative and focus only on purely exogenous demographics in case there was any reporting bias in reported previous vote.

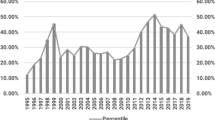

Inasmuch as regional differences in consumer confidence reflect partisan alignments, it is also evidence that the patterns in Tables 1 and 2 do not reflect survey respondents endogenously changing their partisan attachments as the economy changes. The shift from individual-level to aggregate data in studying endogeneity in accountability estimates is a common approach (e.g. Kramer 1983; Whiteley et al. 2016).

These regional differences exist despite the fact that, as we demonstrate below, the economy was growing faster and business conditions were seen as better in Honam than in Yeongnam for most of Park Geun-hye’s presidency. This suggests that presidents are limited in their ability to target economic benefits for the region where their base is concentrated.

Unfortunately, the data do not have confidence intervals by region and so these differences represent the absolute differences without taking into account sampling variation.

The authors calculated growth relative to the previous year from data on regional GDP using data from the Korean Statistical Information Service (https://kosis.kr). Data were not available after 2017 as we write this.

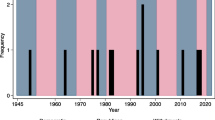

These monthly measures of business condition are strongly correlated with changes in consumer confidence in both regions (Online Appendix 7). The data are available from the Bank of Korea (https://ecos.bok.or.kr/flex/EasySearch_e.jsp).

A dickey-fuller test on the first differenced series allows us to reject the hypothesis that this series has a unit root.

While election panel surveys have been done in several Latin American contexts (e.g. Argentina, Mexico, and Brazil), these party systems have tended to have higher levels of party-system stability (until recently) than South Korea has.

References

Anderson, C., Blais, A., Bowler, S., Donovan, T., & Listhaug, O. (2005). Losers’ consent: Elections and democratic legitimacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anderson, C. J. (2007). The end of economic voting? Contingency dilemmas and the limits of democratic accountability. Annual Review of Political Science, 10, 271–296.

Anderson, C. J., & Guillory, C. A. (1997). Political institutions and satisfaction with democracy: A cross-national analysis of consensus and majoritarian systems. American Political Science Review, 91(1), 66–81.

Anderson, C. J., Mendes, S. M., & Tverdova, Y. V. (2004). Endogenous economic voting: Evidence from the 1997 British election. Electoral Studies, 23(4), 683–708.

Anderson, C. J., & Tverdova, Y. V. (2001). Winners, losers, and attitudes about government in contemporary democracies. International Political Science Review, 22(4), 321–338.

Bartels, L. M. (1996). Uninformed votes: Information effects in presidential elections. American Journal of Political Science, 40(1), 194–230.

Bartels, L. M. (2002). Beyond the running tally: Partisan bias in political perceptions. Political Behavior, 24(2), 117–150.

Bernauer, J., & Vatter, A. (2012). Can’t get no satisfaction with the Westminster model? Winners, losers and the effects of consensual and direct democratic institutions on satisfaction with democracy. European Journal of Political Research, 51(4), 435–468.

Blais, A., & Gélineau, F. (2007). Winning, losing and satisfaction with democracy. Political Studies, 55(2), 425–441.

Bullock, J. G., & Lenz, G. (2019). Partisan bias in surveys. Annual Review of Political Science, 22, 325–342.

Carlin, R. E., Hartlyn, J., Hellwig, T., Love, G. J., Martínez-Gallardo, C., & Singer, M. M. (2018). Public support for Latin American presidents: The cyclical model in comparative perspective. Research & Politics, 5(3), 1–8.

Choi, H. (1995). What determined the 6.27 local election?: Partisanship and regionalism. The Korean Political Science Review, 29(3), 141–161.

Choi, J. Y., Kim, J., & Roh, J. (2017). Cognitive and partisan mobilization in new democracies: The case of South Korea. Party Politics, 23(6), 680–691.

Croissant, A., & Völkel, P. (2012). Party system types and party system institutionalization: Comparing new democracies in East and Southeast Asia. Party Politics, 18(2), 235–265.

Curini, L., Jou, W., & Memoli, V. (2012). Satisfaction with democracy and the winner/loser debate: The role of policy preferences and past experience. British Journal of Political Science, 42(2), 241–261.

Dalton, R. J., & Weldon, S. (2007). Partisanship and party system institutionalization. Party Politics, 13(2), 179–196.

Dalton, R. J. (2010). Ideology, partisanship and democratic development. In L. LeDuc, R. G. Niemi, & P. Norris (Eds.), Comparing democracies: Elections and voting in the 21st century. New York: Sage.

De Boef, S., & Kellstedt, P. M. (2004). The political (and economic) origins of consumer confidence. American Journal of Political Science, 48(4), 633–649.

De Vries, C. E., Hobolt, S. B., & Tilley, J. (2018). Facing up to the facts: What causes economic perceptions? Electoral Studies, 51, 115–122.

Duch, R. M., & Kellstedt, P. M. (2011). The heterogeneity of consumer sentiment in an increasingly homogenous global economy. Electoral Studies, 30(3), 399–405.

Duch, R. M., Palmer, H. D., & Anderson, C. J. (2000). Heterogeneity in perceptions of national economic conditions. American Journal of Political Science, 44(4), 635–652.

Enns, P. K., Kellstedt, P. M., & McAvoy, G. E. (2012). The consequences of partisanship in economic perceptions. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(2), 287–310.

Erikson, R. S., MacKuen, M. B., & Stimson, J. A. (2002). The macro polity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Evans, G., & Andersen, R. (2001). Endogenizing the economy: Political preferences and economic perceptions across the electoral cycle. Chicago: In Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association.

Evans, G., & Andersen, R. (2006). The political conditioning of economic perceptions. Journal of Politics, 68(1), 194–207.

Evans, G., & Chzhen, K. (2016). Re-evaluating the valence model of political choice. Political Science Research and Methods, 4(1), 199–220.

Evans, G., & Pickup, M. (2010). Reversing the causal arrow: The political conditioning of economic perceptions in the 2000–2004 US presidential election cycle. The Journal of Politics, 72(4), 1236–1251.

Fiorina, M. P. (1981). Retrospective voting in American national elections. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Green, D. P., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2004). Partisan hearts and minds: Political parties and the social identities of voters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Han, J. (2018). Partisan media and polarized opinion in South Korea: A review. In W. Shin, K. H. Kim, & C. W. Kim (Eds.), Digital Korea: Digital technology and the change of social life (pp. 77–101). Seoul: Hanul Academy.

Hellmann, O. (2014). Party system institutionalization without parties: Evidence from Korea. Journal of East Asian Studies, 14(1), 53–84.

Hetherington, M. J. (1996). The media’s role in forming voters’ national economic evaluations in 1992. American Journal of Political Science, 40(2), 372–395.

Hollander, B. A. (2008). Tuning out or tuning elsewhere? Partisanship, polarization, and media migration from 1998 to 2006. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 85(1), 23–40.

Huang, M. H. (2011). Popular discontent, divided perceptions, and political polarization in Taiwan. International Review of Sociology, 21(2), 413–432.

Hwang, A. R. (2008). A multiple indicators approach of partisan attitudes: An analysis of the effect of partisanship on voters’ choice in the 17th presidential election in Korea. Political Research, 1, 86–110.

Jang, S. J. (2012). The Korean voters’ attitude toward political parties: Ideological and psychological foundation of party support and party voting. In C. W. Park & W. T. Kang (Eds.), Analyzing the 2012 national assembly election in South Korea (pp. 175–203). Seoul: Nanam.

Johnston, R., Sarker, R., Jones, K., Bolster, A., Propper, C., & Burgess, S. (2005). Egocentric economic voting and changes in party choice: Great Britain 1992–2001. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 15(1), 129–144.

Jones, P. E. (Forthcoming). Partisanship, political awareness, and retrospective evaluations, 1956–2016. Political Behavior, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09543-y.

Kang, W. T. (2008). How ideology divides generations: The 2002 and 2004 South Korean elections. Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue Canadienne de Science Politique, 41(2), 461–480.

Kayser, M. A., & Wlezien, C. (2011). Performance pressure: Patterns of partisanship and the economic vote. European Journal of Political Research, 50(3), 365–394.

Kim, M. (2009). Cross-national analyses of satisfaction with democracy and ideological congruence. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 19(1), 49–72.

Kramer, G. H. (1983). The ecological fallacy revisited: Aggregate-versus individual-level findings on economics and elections, and sociotropic voting. American Political Science Review, 77(1), 92–111.

Lacy, D., & Christenson, D. P. (2017). Who votes for the future? Information, expectations, and endogeneity in economic voting. Political Behavior, 39(2), 347–375.

Ladner, M., & Wlezien, C. (2007). Partisan preferences, electoral prospects, and economic expectations. Comparative Political Studies, 40(5), 571–596.

Levendusky, M. (2013). Partisan media exposure and attitudes toward the opposition. Political Communication, 30(4), 565–581.

Lee, D. O., & Brunn, S. D. (1996). Politics and regions in Korea: An analysis of the recent presidential election. Political Geography, 15(1), 99–119.

Lewis-Beck, M. S. (2006). Does economics still matter? Econometrics and the vote. The Journal of Politics, 68(1), 208–212.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., Nadeau, R., & Elias, A. (2008). Economics, party, and the vote: Causality issues and panel data. American Journal of Political Science, 52(1), 84–95.

Lupu, N. (2015). Partisanship in Latin America. In R. E. Carlin, M. M. Singer, & E. J. Zechmeister (Eds.), The Latin American voter: Pursuing representation and accountability in challenging contexts (pp. 226–245). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Mattes, R., & Krönke, M. (Forthcoming). The consequences of partisanship in Africa. In H. Oscarsson, & S. Holmberg (Eds.), Research handbook on political partisanship (pp. 368–380). Cheltenham, UK.

Martin, G. J., & Yurukoglu, A. (2017). Bias in cable news: Persuasion and polarization. American Economic Review, 107(9), 2565–2599.

Nadeau, R., Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Bélanger, É. (2013). Economics and elections revisited. Comparative Political Studies, 46(5), 551–573.

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2010). When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions. Political Behavior, 32(2), 303–330.

Nyhan, B., Reifler, J., & Ubel, P. A. (2013). The hazards of correcting myths about health care reform. Medical Care, 51(2), 127–132.

Okolikj, M., & Hooghe, M. (Forthcoming). Is there a partisan bias in the perception of the state of the economy? A comparative investigation of European countries, 2002–2016. International Political Science Review, https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512120915907

Park, C. W. (1993). Party votes in the 14th National Assembly elections. In N. Y. Lee (Ed.), The Korean election I (pp. 137–174). Seoul: Nanam.

Park, W. H. (2013). Reconstruction of party identification. In C. W. Park & W. T. Kang (Eds.), Analyzing the 2012 presidential election in South Korea (pp. 51–74). Seoul: Nanam.

Parker-Stephen, E. (2013). Clarity of responsibility and economic evaluations. Electoral Studies, 32(3), 506–511.

Powell, G. B., Jr., & Whitten, G. D. (1993). A cross-national analysis of economic voting: Taking account of the political context. American Journal of Political Science, 37(2), 391–414.

Rice, T. W., & Hilton, T. A. (1996). Partisanship over time: A comparison of United States panel data. Political Research Quarterly, 49(1), 191–201.

Rico, G., & Liñeira, R. (2018). Pass the buck if you can: How partisan competition triggers attribution bias in multilevel democracies. Political Behavior, 40(1), 175–196.

Schaffner, B. F., & Roche, C. (2017). Misinformation and motivated reasoning: Responses to economic news in a politicized environment. Public Opinion Quarterly, 81(1), 86–110.

Shin, Y. (2012). Is party identification responsible in Korea? An explanation of unstable party identification in terms of voters’ evaluations. Korea Observer, 43(2), 233–252.

Singh, S., Karakoç, E., & Blais, A. (2012). Differentiating winners: How elections affect satisfaction with democracy. Electoral Studies, 31(1), 201–211.

Singh, S., Lago, I., & Blais, A. (2011). Winning and competitiveness as determinants of political support. Social Science Quarterly, 92(3), 695–709.

Stevenson, R. T., & Duch, R. (2013). The meaning and use of subjective perceptions in studies of economic voting. Electoral Studies, 32(2), 305–320.

Stockton, H. (2001). Political parties, party systems, and democracy in East Asia: Lessons from Latin America. Comparative Political Studies, 34(1), 94–119.

Stroud, N. J. (2008). Media use and political predispositions: Revisiting the concept of selective exposure. Political Behavior, 30(3), 341–366.

Tverdova, Y. V. (2011). See no evil: Heterogeneity in public perceptions of corruption. Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue Canadienne de Science Politique, 44(1), 1–25.

Whiteley, P., Clarke, H., Sanders, D., & Stuart, M. (2016). Hunting the Snark: A reply to “Re-evaluating valence models of political choice”. Political Science Research and Methods, 4(1), 221–240.

Wlezien, C., Franklin, M., & Twiggs, D. (1997). Economic perceptions and vote choice: Disentangling the endogeneity. Political Behavior, 19(1), 7–17.

Wong, J. (2014). South Korea’s weakly institutionalized party system. In A. Hicken & E. M. Kuhonta (Eds.), Party system institutionalization in Asia: Democracies, autocracies, and the shadows of the past (pp. 260–279). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Zaller, J. R. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Korean Social Science Data Center for making the survey data available; the analysis and the conclusions are the responsibility of the authors. The data and replication code are available on the Political Behavior Dataverse page (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LIVEUK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, H., Singer, M.M. The Partisan Origins of Economic Perceptions in a Weak Party System: Evidence from South Korea. Polit Behav 44, 341–364 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09622-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09622-5