Abstract

Political sophistication systematically affects the structure, crystallization, and use of political values, but it remains unclear if sophistication manifests similar effects on human values. This paper integrates Shalom Schwartz (Adv Exp Soc Psychol 25:1–65, 1992, J Soc Issues 50:19–45, 1994) theory of human values with sophistication interaction theory to examine the degree to which education and political interest condition the structure, crystallization, and use of an important subset of values. We theorize that human values are (1) identically structured and equally crystallized in sophistication-stratified populations and (2) that relationships between human values and ideological judgments grow stronger at higher levels of sophistication. Using data from a nationally representative sample of 10,765 Americans, we compare extremely sophisticated individuals (e.g., people with doctorates) and extremely unsophisticated individuals (e.g., high school dropouts) to demonstrate that neither education nor political interest affect value structure and crystallization. Sophistication has real, if somewhat limited, effects on value usage.

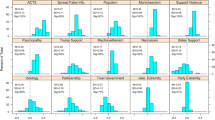

Source 2015 author survey

Source 2015 author survey

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

16 March 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09785-3

Notes

Because we do not take up the remaining Schwartz values, we cannot speak their structure, crystallization, and use.

The low education group includes respondents with a high school degree or less. The moderate education group includes those with some college. The high education group includes those who graduated from a four-year college. The egalitarian items are v085162–v085167. The family value items are v085139-v085142.

There is some uncertainty on this. For idiosyncratic reasons, some of this work does not include all 10 value types (e.g., Cieciuch et al. 2013; Knafo and Spinath 2011). Also, some studies find modest deviations in value structure between adult and adolescent/pre-adolescent samples (e.g., Bilsky et al. 2013).

Data and code to replicate the analyses can be found at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/O8MLXX. This project was funded by a grant to the senior author from the Russell Sage Foundation (award number 83-15-28). GfK relies on a random sampling technique—address based sampling—to recruit respondents into its online panel. This stands in contrast to other online samples in which people self-select into the panel and are matched to population benchmarks via post-hoc weights.

We measured symbolic ideology using a branched administration format. The GfK ideology question does not include the wording “or haven’t you thought much about this” in the root question, which stands in contrast to the standard NES measure of ideological id. Respondents could select “unsure” instead of one of the seven self-placement options in the root question. Individuals who chose “unsure” received a follow-up asking if they had to choose, would they identify as liberal or conservative (those who selected one of these were scored as “slightly liberal” or “slightly conservative” on the seven-point scale). When we report that no more than 7% of respondents failed to answer the ideological id question across the sub-groups, we are referring specifically to the second stage of this question. Note that 12% of our sample did not provide an answer to the first stage of this question.

We do not reject the null hypothesis of equal factor loadings, but it is close. Two of 18 univariate constraints are p < .05 and another two are p < .06.

Given that there is no meaningful substantive difference in scale reliabilities across the samples, we do not employ formal tests to determine if these differences are statistically significant.

We control for gender, marital status, race/ethnicity, income, age, and party identification. We measure age in years. Gender, married, African American, and Hispanic are dummy variables. Income is a scale. We use dummy variables for Democrat and Republican. Pure independents serve as the reference category. All variables, with the exception of age, are keyed to range from zero to one.

The EIV coefficients always exceed the OLS coefficients in magnitude because the measurement error corrections boost their size.

There are some sophistication differences across samples, but these are not always in the expected direction. For example, in the EIV education model (see Table S3 in the online materials), the conservation effect is significantly larger in the HS/HS+ group (0.69) than the doctorate group (0.52).

In the supplemental materials online, we demonstrate that our results are robust in a number of ways. First, we acknowledge that our sophistication coding scheme is unusual. For example, we place respondents without a high school degree in one category and respondents with high school degrees/some post-high school education into a separate category. A more conventional tack places people with up to a high school degree in one category and respondents with some college in a second category. To ensure our findings are not a function of unorthodox classification, we replicated the analyses using conventional bins. We found qualitatively similar results (see Tables S9-S11 for the MGCFA estimates and Tables S12–S19 for the OLS and EIV models).

Second, we remind readers that to maintain consistency with our MGCFA analyses, we estimated separate OLS and EIV models using the same groups. We used formal Wald tests to determine if the universalism and conservation coefficients differed significantly across the groups (the notes in the figures and supplemental tables report these results). To check the robustness of our findings, we re-estimated the OLS models using value x sophistication interaction terms. Since prior studies show that politically sophisticated respondents rely more on party id to inform their political choices than the unsophisticated (Berinsky 2009; Zaller 1992), we also included party id x sophistication terms. In lieu of the binned measures of education, we deployed an 18-point measure of the years of formal schooling. In place of our binned measure of political interest, we used an unbinned, eight-point measure. We then reset both moderators onto a 0-1 scale. The estimates appear in Tables S20–S21. These results largely match what we report in the paper. To begin, we find that sophistication does not systematically strengthen the relationship between values and symbolic ideology. Only one of the four value x sophistication interaction terms is significant: the conservation x education coefficient = 0.20 (t = 2.02, see Table S20). This estimate means that the impact of conservation on symbolic ideology is significantly higher for people with doctorates compared to people with no formal education. However, the impact of conservation on symbolic ideology among people with no formal education is significant (b = 0.22, t = 2.85). There are only 20 respondents in our sample of 10,765 respondents with no formal education, so this result overstates the substantive impact of education. Second, sophistication always strengthens the impact universalism and conservation have on operational ideology, which matches what we reported in the text. Third, six of the eight party id x sophistication terms are significant in the expected direction, which justifies our decision to include them in the model.

The “equal opportunities” item in the universalism battery and the “traditional values and beliefs” item in the conservation battery are very similar to items that appear in the standard NES measures of egalitarianism and traditional family values. As a final robustness check, we re-estimated the OLS models after dropping each of these items from the respective human values scales. The estimates in the online tables (S23-S26) reveal the same pattern of results reported in the text.

References

Bartle, J. (2000). Political awareness, opinion constraint, and the stability of ideological predispositions. Political Studies, 48(3), 467–484.

Berinsky, A. J. (2009). In time of war: Understanding American public opinion from World War II to Iraq. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Bilsky, W., Döring, A. K., van Beeck, F., Rose, I., Schmitz, J., Aryus, K., et al. (2013). Assessment of children’s value structures and value preferences: Testing and expanding the limits. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 72(3), 123–136.

Brewer, P. R. (2003). Values, political knowledge, and public opinion about gay rights: A framing-based account. Public Opinion Quarterly, 67(2), 173–201.

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: Guilford Press.

Bubeck, M., & Bilsky, W. (2004). Value structure at an early age. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 63(1), 31–41.

Caprara, G. V., Vecchione, M., Schwartz, S. H., Schoen, H., & Caprara, M. G. (2017). Basic values, ideological self-placement and voting: A cross-cultural study. Cross-Cultural Research, 51(4), 388–411.

Chong, D., McClosky, H., & Zaller, J. (1983). Patterns of support for democratic and capitalist values in the United States. British Journal of Political Science, 13(4), 401–440.

Cieciuch, J., Döring, A. K., & Harasimczuk, J. (2013). Measuring Schwartz’s values in childhood: Multidimensional scaling across instruments and cultures. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 10(5), 625–633.

Converse, P. E. (1970). Attitudes and non-attitudes: Continuation of a dialogue. In E. R. Tufte (Ed.), The quantitative analysis of social problems (pp. 168–189). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Converse, P. E. (1980). Rejoinder to Judd and Milburn. American Sociological Review, 45(4), 644–646.

Dancey, L., & Sheagley, G. (2013). Heuristics behaving badly: Party cues and voter knowledge. American Journal of Political Science, 57(2), 312–325.

Ellis, C., & Stimson, J. A. (2012). Ideology in America. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Federico, C. M., & Malka, A. (2018). The contingent, contextual nature of the relationship between needs for security and certainty and political preferences: Evidence and implications. Advances in Political Psychology, 39(S1), 3–48.

Feldman, S. (1988). Structure and consistency in public opinion: The role of core beliefs and values. American Journal of Political Science, 32(2), 416–440.

Feldman, S. (2003). Values, ideology, and the structure of political attitudes. In D. O. Sears, L. Huddy, & R. Jervis (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political psychology (pp. 477–508). New York: Oxford University Press.

Fischer, R., & Smith, P. B. (2004). Values and organizational justice performance and seniority-based allocation criteria in the United Kingdom and Germany. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35(6), 669–688.

Goren, P. (2001). Core principles and policy reasoning in mass publics: A test of two theories. British Journal of Political Science, 31(1), 159–177.

Goren, P. (2004). Political sophistication and policy reasoning: A reconsideration. American Journal of Political Science, 48(3), 462–478.

Goren, P., Schoen, H., Reifler, J., Scotto, T., & Chittick, W. O. (2016). A unified theory of value-based reasoning and US public opinion. Political Behavior, 38(4), 977–997.

Homer, P. M., & Kahle, L. K. (1988). A structural equation test of the value-attitude-behavior hierarchy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(4), 638–646.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55.

Iyengar, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and loathing across party lines: New evidence on group polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 690–707.

Johnston, C. D., Lavine, H. G., & Federico, C. M. (2017). Open versus closed: Personality, identity, and the politics of redistribution. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Jost, J. T. (2016). The end of the end of ideology. American Psychologist, 61(7), 651–670.

Kalmoe, N. P. (2020). Uses and abuses of ideology in political psychology. Political Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12650.

Katz, D. (1960). The functional approach to the study of attitudes. Public Opinion Quarterly, 24(2), 163–204.

Kinder, D. R., & Kalmoe, N. P. (2017). Neither liberal nor conservative: Ideological innocence in the American public. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Knafo, A., & Spinath, F. M. (2011). Genetic and environmental influences on girls’ and boys’ gender-typed and gender-neutral values. Developmental Psychology, 47(3), 726–731.

Lau, R. R., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2006). How voters decide: Information processing in election campaigns. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lupton, R. N., Myers, W. M., & Thornton, J. R. (2015). Political sophistication and the dimensionality of elite and mass attitudes. Journal of Politics, 77(2), 368–380.

Maio, G. R., & Olson, J. M. (1995). Relations between values, attitudes, and behavioral intentions: The moderating role of attitude function. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 31(3), 266–285.

Malka, A., Soto, C. J., Inzlicht, M., & Lelkes, Y. (2014). Do needs for security and certainty predict cultural and economic conservatism? A cross-national analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(6), 1031–1051.

McCann, J. A. (1997). Electoral choices and core value change: The 1992 presidential campaign. American Journal of Political Science, 41(2), 564–583.

Michaud, K. E. H., Carlisle, J. E., & Smith, E. R. A. N. (2009). The relationship between cultural values and political ideology, and the role of political knowledge. Political Psychology, 30(1), 27–42.

Piurko, Y., Schwartz, S. H., & Davidov, E. (2011). Basic personal values and the meaning of left-right political orientations. Political Psychology, 32(4), 537–561.

Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. New York: Free Press.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 Countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 1–65.

Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values? Journal of Social Issues, 50(1), 19–45.

Schwartz, S. H., & Boehnke, K. (2004). Evaluating the structure of human values with confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 38(3), 230–255.

Schwartz, S. H., Cieciuch, J., Vecchione, M., Davidov, E., & Konty, M. (2012). Refining the theory of basic individual values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(4), 663–688.

Schwartz, S. H., Melech, G., Lehmann, A., Burgess, S., Harris, M., & Owens, V. (2001). Extending the cross-cultural validity of the theory of human values with a different method of measurement. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(5), 519–542.

Sniderman, P. M., Brody, R. A., & Tetlock, P. E. (1991). Reasoning and choice. Explorations in political psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Spini, D. (2003). Measurement equivalence of 10 value types from the Schwartz value survey across 21 countries. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology, 34(1), 3–23.

Steinmetz, H., Schmidt, P., Tina-Booth, A., Wieczorek, S., & Schwartz, S. H. (2009). Testing measurement invariance using multigroup CFA: Differences between educational groups in human values measurement. Quality and Quantity, 43(4), 599–616.

Thorisdottir, H., Jost, J. T., Liviatan, I., & Shrout, P. E. (2007). Psychological needs and values underlying left-right political orientation: Cross-national evidence from Eastern and Western Europe. Public Opinion Quarterly, 71(2), 175–203.

Verplanken, B., & Holland, R. W. (2002). Motivated decision making: Effects of activation and self-centrality of values on choices and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(3), 434–447.

Zaller, J. R. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Zaller, J. (2012). What nature and origins leaves out. Critical Review, 24(4), 569–642.

Zingher, J., & Flynn, M. E. (2019). Does polarization affect even the inattentive? Assessing the relationship between political sophistication, policy orientations, and elite cues. Electoral Studies, 57(1), 131–142.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goren, P., Smith, B. & Motta, M. Human Values and Sophistication Interaction Theory. Polit Behav 44, 49–73 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09611-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09611-8