Abstract

Cues and heuristics—like party, gender, and race/ethnicity—help voters choose among a set of candidates. We consider candidate professional experience—signaled through occupation—as a cue that voters can use to evaluate candidates’ functional competence for office. We outline and test one condition under which citizens are most likely to use such cues: when there is a clear connection between candidate qualifications and the particular elected office. We further argue that voters in these contexts are likely to make subtle distinctions between candidates, and to vote accordingly. We test our account in the context of local school board elections, and show—through both observational analyses of California election results and a conjoint experiment—that (1) voters favor candidates who work in education; (2) that voters discriminate even among candidates associated with education by only favoring those with strong ties to students; and (3) that the effects are not muted by partisanship. Voters appear to value functional competence for office in and of itself, and use cues in the form of candidate occupation to assess who is and who is not fit for the job.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The author did not provide standard errors and so we cannot calculate whether these coefficients, which are very close in magnitude, are statistically different from one another.

Per the California Code of Regulations, Ballot Designations. http://www.sos.ca.gov/administration/regulations/current-regulations/elections/ballot-designations/#section-20714.

A copy of the ballot designation worksheet can be found here: http://elections.cdn.sos.ca.gov/ballot-designation-worksheet/ballot-designation-worksheet.pdf.

These two features make it seem less plausible that candidates can stretch the reality of their backgrounds for political gain. Yet, decisions about ballot designations are certainly likely to be influenced by the attributes of their opponent. In our setting, highlighting a background in education would seem to be most electorally beneficial when the opposing candidates come from different, less-relevant fields. Future research should certainly address the strategic nature of ballot designations, and its consequences for election outcomes.

It is possible that these three categories reflect both experience working with students as well class differences. For example, we may simply expect candidates in the “high” and “medium” education category to fare better than those in the “low” education category simply because the jobs in the former are viewed more generally by society as “better” jobs, reflecting higher status. We return to this point later in the manuscript as we interpret our results.

We used the following as a database of female first names: http://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs/project/ai-repository/ai/areas/nlp/corpora/names/female.txt.

We recognize that using a Hispanic surname match is not a perfect indicator of whether a respondent is Hispanic or not. Some candidates, especially married women, with Hispanic surnames may not identify as Hispanic. Nevertheless, this is a reasonable proxy. And perhaps most importantly, regardless of whether the candidate is Hispanic-born or not, our coding reflects the information that voters may use in evaluating candidates.

We also run a model which excludes those candidates who ran unopposed. These results are presented in Table 2 of the Appendix, and are substantively and statistically similar to these presented below.

The 95% CI for the difference between the “high” education group and “business owner” is [2.79, 4.27], and the 95% CI for the difference between the “medium” education group and “business owner” is [0.79, 2.27].

This study was approved by the Office of the Institutional Review Board at the University of New Mexico (1129029-1) and the Office of the Human Research Protection Program at the University of California, Los Angeles (IRB#17-001659).

The order in which the attributes appeared was randomized in each of the three tasks.

We also calculated three conditional AMCEs (i.e., an exploration of heterogeneous treatment effects) of occupation on vote choice: one where the party of the candidate and the party of the respondent are the same (i.e., Republican and Republican/Republican and lean-Republican, Democrat and Democrat/Democrat and lean-Democrat, or no party (candidate) and neither party (voter)), one where the two differ, and one where the candidate had no party affiliation. These analyses re-run the same model, but include an interaction between the occupation attribute and indicator for shared party affiliation and allow us to determine whether the effects uncovered so far appear only when the candidate and respondent share a party affiliation. We find that that the effect of occupation does not differ dramatically depending on whether the respondent shares the party of the candidate. Figure 4 in the Appendix presents the results of this analysis.

References

Abramowitz, A. I., & Webster, S. (2016). The rise of negative partisanship and the nationalization of U.S. elections in the 21st century. Electoral Studies,41(1), 12–22.

Ahler, D. J. (2014). Self-fulfilling misperceptions of public polarization. Journal of Politics,76(3), 607–620.

Atkeson, L. R., & Partin, R. W. (2001). Candidate advertisements, media coverage, and citizen attitudes: The agendas and roles of senators and governors in a federal system. Political Research Quarterly,54(4), 795–813.

Barreto, M. A., Villarreal, M., & Woods, N. D. (2005). Metropolitan Latino political behavior: Voter turnout and candidate preference in Los Angeles. Journal of Urban Affairs,27(1), 71–79.

Berinsky, A. J., Huber, G. A., & Lenz, G. S. (2012). Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Political Analysis,20(3), 351–368.

Bianco, W. T. (1984). Strategic decisions on candidacy in U.S. congressional districts. Legislative Studies Quarterly,9(2), 351–364.

Bond, J. R., Fleisher, R., & Talbert, J. C. (1997). Partisan differences in candidate quality in open seat House races, 1976-1994. Political Research Quarterly,50(2), 182–299.

Box-Steffensmeier, J. M., Jacobson, G. C., & Grant, J. T. (2000). Question wording and the House vote choice: Some experimental evidence. Public Opinion Quarterly,64(3), 257–270.

Bullock, C. S., III. (1994). Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, districting formats, and the election of African Americans. Journal of Politics,56(4), 1098–1105.

Bullock, C. S., III, & Campbell, B. A. (1984). Racist or racial voting the 1981 Atlanta municipal elections. Urban Affairs Quarterly,20(2), 149–164.

Butler, D. M., & Powell, E. N. (2014). Understanding the party brand: Experimental evidence on the role of valence. Journal of Politics,76(2), 492–505.

Cadei, E. (2018). Why an election tradition is banned in other states. Sacramento Bee. Retrieved June 9, 2018, from, http://www.sacbee.com/news/politics-government/capitol-alert/article207850079.html.

Cox, G. W., & Katz, J. R. (1996). Why did the incumbency advantage in U.S. House elections grow? American Journal of Political Science,40(2), 478–497.

Crawford, E. (2018). How nonpartisan ballot design conceals partisanship: A survey experiment of school board members in two states. Political Research Quarterly,71(1), 143–156.

Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. New York: Harper & Row.

Dubois, P. L. (1984). Voting cues in nonpartisan trial court elections: A multivariate assessment. Law and Society Review,18(3), 395–436.

Erikson, R. S. (1971). The advantage of incumbency in congressional elections. Polity,3(3), 395–405.

Ferreira, F., & Gyourko, J. (2009). Do political parties matter? Evidence from U.S. cities. Quarterly Journal of Economics,124(1), 399–422.

Ferreira, F., & Gyourko, J. (2014). Does gender matter for political leadership? The case of U.S. mayors. Journal of Public Economics,112, 24–39.

Gelman, A., & King, G. (1990). Estimating incumbency advantage without bias. American Journal of Political Science,34(4), 1142–1164.

Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J., & Yamamoto, T. (2014). Causal inference in conjoint analysis: Understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Political Analysis,22(1), 1–30.

Hersh, E. D., & Schaffner, B. F. (2013). Targeted campaign appeals and the value of ambiguity. Journal of Politics,75(2), 520–534.

Huddy, L. (1994). The political significance of voters’ gender stereotypes”. In M. X. Delli Carpini, L. Huddy, & R. Y. Shapiro (Eds.), Research in micropolitics: New directions in political psychology. Greenwich: JAI Press.

Huddy, L., & Terkildsen, N. (1993). The consequences of gender stereotypes for women candidates at different levels and types of offices. Political Research Quarterly,46(3), 503–525.

Iyengar, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and loathing across party lines: New evidence on group polarization. American Journal of Political Science,59(3), 690–707.

Jacobson, G. C., & Kernell, S. (1981). Strategy and choice in congressional elections. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Kirkland, P. A., & Coppock, A. (2017). Candidate choice without party labels: New insights from conjoint survey experiments. Political Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-017-9414-8.

Klein, D., & Baum, L. (2001). Ballot information and voting decisions in judicial elections. Political Research Quarterly,54(4), 709–728.

Koch, J. W. (2000). Do citizens apply gender stereotypes to infer candidates’ ideological orientations? Journal of Politics,62(2), 414–429.

Krasno, J. S., & Green, D. P. (1988). Preempting quality challengers in House elections. Journal of Politics,50(4), 920–936.

Lien, P. (1998). Does the gender gap in political attitudes and behavior vary across racial groups? Political Research Quarterly,51(4), 869–894.

Longoria, T., Jr. (1999). The impact of office on cross-racial voting: Evidence from the 1996 Milwaukee mayoral election. Urban Affairs Review,34(4), 596–603.

Lublin, D. I. (1994). Quality, not quantity: Strategic politicians in U.S. Senate elections, 1952-1990. Journal of Politics,56(1), 228–241.

Lupia, A., & McCubbins, M. D. (1998). The Democratic dilemma: Can citizens learn what they need to know?. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Matson, M., & Fine, T. S. (2006). Gender, ethnicity and ballot information: Ballot cues in low-information elections. State Politics and Policy Quarterly,6(1), 49–72.

McDermott, M. L. (1997). Voting cues in low-information elections: Candidate gender as a social information variable in contemporary United States elections. American Journal of Political Science,41(1), 270–283.

McDermott, M. L. (1998). Race and gender cues in low-information elections. Political Research Quarterly,51(4), 895–918.

McDermott, M. L. (2005). Candidate occupations and voter information shortcuts. Journal of Politics,67(1), 201–219.

Mechtel, M. (2013). It’s the occupation, stupid! Explaining candidates’ success in low-information elections. European Journal of Political Economy,33(2), 53–70.

Mondak, J. J. (1993). Public opinion and heuristic processing of source cues. Political Behavior,29(2), 167–192.

Mueller, J. E. (1970). Choosing among 133 candidates. Public Opinion Quarterly,34(3), 395–402.

Nakanishi, M., Cooper, L. G., & Kassarjian, H. H. (1974). Voting for a political candidate under conditions of minimal information. Journal of Consumer Research,1(2), 36–43.

Partin, R. W. (2001). Campaign intensity and voter information: A look at gubernatorial contests. American Politics Research,29(2), 115–140.

Pomper, G. M. (1975). Voters’ choice: Varieties of American electoral behavior. New York: Dodd Meade.

Popkin, S. L. (1994). The reasoning voter: Communication and persuasion in presidential campaigns. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rahn, W. M. (1993). The role of partisan stereotypes in information processing about political candidates. American Journal of Political Science,37(2), 472–496.

Rapoport, R. B., Metcalf, K. L., & Hartman, J. A. (1989). Candidate traits and voter inferences: An experimental study. Journal of Politics,51(4), 917–932.

Rosenstone, S. J., & Hansen, J. M. (1993). Mobilization, participation, and democracy in America. New York: Macmillan.

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2006). Where women run: Gender and party in the American states. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Schaffner, B. F., Streb, M., & Wright, G. (2001). Teams without uniforms: The nonpartisan ballot in state and local elections. Political Research Quarterly,54(1), 7–30.

Sniderman, P. M. (2017). The democratic faith: Essays on democratic citizenship. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sniderman, P. M., Brody, R. A., & Tetlock, P. E. (1991). Reasoning and choice: Explorations in political psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Squire, P. (1989). Challengers in U.S. Senate elections. Legislative Studies Quarterly,14(4), 531–547.

Squire, P., & Smith, E. (1988). The effect of partisan information on voters in nonpartisan elections. Journal of Politics,50(1), 169–179.

Trounstine, J. (2011). Evidence of a local incumbency advantage”. Legislative Studies Quarterly,36(2), 255–280.

Vanderleeuw, J. M. (1990). A city in transition: The impact of changing composition on voting behavior”. Social Science Quarterly,71(2), 326–338.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kathleen Hale, participants in UCLA’s Political Psychology lab and at MPSA 2018, as well as the anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on earlier drafts. Brian Hamel acknowledges the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program for support. Replication code and data are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/1HPT9N. All errors are our responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 2 and 3 and Fig. 4.

Survey Instrument

What year were you born (e.g., 1980)?

What is your gender?

Male

Female

Other [Please Specify]

What racial or ethnic group best describes you?

White

Black or African-American

Asian

Hispanic or Latino

Other [Please Specify]

To the best of your knowledge, what was your total family income before taxes in 2016?

Below $21,000

$21,000–$41,999

$42,000–$59,999

$60,000–$79,999

$80,000–$99,999

$100,000 or more

Don’t know

What is the highest level of school you have completed or the highest degree you have received?

Less than high school

High school graduate—high school diploma or equivalent (for example: GED)

Some college but no degree

Associate degree in college—occupational/vocational program

Associate degree in college—academic program

Bachelor’s degree (for example: BA, AB, BS)

Graduate degree (for example: MA, MS, MEng, MBA, MD, DVM, JD, Phd)

Other [Please Specify]

Generally speaking, do you usually think of yourself as a Democrat, Republican, an independent, or what?

Democrat

Republican

Independent

Other [Please Specify]

(if Democrat or Republican was selected)—Would you say that is strong or weak?

Strong

Weak

(if Independent was selected)—Would you say that you lean toward one of the parties?

Lean Democrat

Lean Republican

Neither

We hear a lot of talk these days about liberals and conservatives. Here is a seven-point scale on which political views that people might hold are arranged from extremely liberal to extremely conservative. Where would you place yourself on this scale or haven’t you thought much about this?

Extremely liberal

Liberal

Slightly liberal

Moderate; middle of the road

Slightly conservative

Conservative

Extremely conservative

Haven’t thought much about this

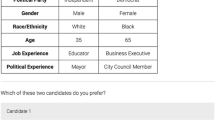

Conjoint Attributes

Gender:

Female

Male

Incumbency Status:

No

Yes

Occupation:

Attorney

Business Owner

School Guidance Counselor

School Janitor

School Teacher

Party:

Democrat

No Party

Republican

Race:

Asian

Black or African-American

Hispanic or Latino

White

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Atkeson, L.R., Hamel, B.T. Fit for the Job: Candidate Qualifications and Vote Choice in Low Information Elections. Polit Behav 42, 59–82 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9486-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9486-0