Abstract

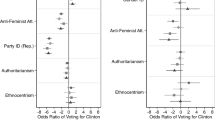

On November 8, 2016 Donald Trump, a man with no office-holding experience, won the Electoral College, defeating the first woman to receive the presidential nomination from a major party. This paper offers the first observational test of how sexism affects presidential vote choice in the general election, adding to the rich literature on gender and candidate success for lower-level offices. We argue that the 2016 election implicated gender through Hillary Clinton’s candidacy and Donald Trump’s sexist rhetoric, and activated gender attitudes such that sexism is associated with vote choice. Using an Election Day exit poll survey of over 1300 voters conducted at 12 precincts in a mid-size city and a national survey of over 10,000 White and Black Americans, we find that a politically defined measure of sexism—the belief that men are better suited emotionally for politics than women—predicts support for Trump both in terms of vote choice and favorability. We find the effect is strongest and most consistent among White voters. However, a domestically defined measure of sexism—whether men should be in control of their wives—offers little explanatory power over the vote. In total, our results demonstrate the importance of gender in the 2016 election, beyond mere demographic differences in vote choice: beliefs about gender and fitness for office shape both White men and women’s preferences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The majority of Muslim Americans are White, but they comprise a small segment of the overall population. Therefore we do not expect the inclusion of any Muslim Americans among White respondents to seriously change any results.

A recent FiveThirtyEight article identified Oklahoma City as one of the ten metropolitan areas that most closely match national demographics (age, educational attainment, race, and ethnicity) in the country (Kolko 2016).

Undergraduate students received course credit for completing CITI training, attending three instructional sessions, surveying on Election Day, and attending a data entry session. Altogether, students received between 10 and 12 hours of instruction. While we were at the polling locations all day, undergraduates typically recruited respondents for 2–4 hours each. In field training students practiced random selection, learned when to direct a participant toward one of the authors, and practiced interacting with respondents. The latter was instrumental in resolving pollster idiosyncrasies, with the aim of consistent survey delivery.

The lower proportion of Latinos in the Latino precincts is relatively unsurprising given the lower rate of Latino turnout (Krogstad et al. 2016) and the relatively recent immigration history in the city.

We categorize respondents’ race from a mark-one-or-more measure. This measure included Hispanic/Latino as a racial category. From there, we identify respondents with a singular racial category if that is the only group they marked. Respondents who selected more than one category are coded as “Mixed race” given recent research on the political uniqueness of those who identify with two or more racial groups (Davenport 2016).

We measure party registration rather than party ID so that we can examine the quality of our sample against the known population parameters from party registration statistics for each precinct.

Ideally, we would specify models for each racial group separately, however the sample sizes for each non-White racial group are too small.

That the effects of sexism would be independent from other anti-outgroup attitudes is not unexpected, as the structure of the gender schema does not rely on the same social segregation and negative feelings toward outgroups that structure the racial schema. Instead, gender schemas are built on intimate contact between men and women and feelings of mutual dependence (Huddy and Carey 2009; Ridgeway 2011; Winter 2008).

References

Achen, C. H. (1982). Interpreting and using regression. Sage University Paper 29 (Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Alexander, D., & Andersen, K. (1993). Gender as a factor in the attribution of leadership traits. Political Research Quarterly, 46(3), 527–545.

Arciniega, G. M., Anderson, T. C., Tovar-Blank, Z. G., & Tracey, T. J. G. (2008). Toward a fuller conception of machismo: Development of a traditional machismo and caballerismo scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55(1), 19–33.

Ashburn-Nardo, L., Knowles, M. L., & Monteith, M. J. (2003). Black Americans’ implicit racial associations and their implications for intergroup judgment. Social Cognition, 21(1), 61–87.

Barnett, B. M. (1993). Invisible Southern black women leaders in the Civil Rights Movement: The triple constraints of gender, race, and class. Gender & Society, 7(2), 162–182.

Bauer, N. M. (2015). Emotional, sensitive, and unfit for office? Gender stereotype activation and support female candidates. Political Psychology, 36(6), 691–708.

Bauer, N. M. (2017). The effects of counterstereotypic gender strategies on candidate evaluations. Political Psychology, 38(2), 279–295.

Baum, M. A. (2005). Talking the vote: Why presidential candidates hit the talk show circuit. American Journal of Political Science, 49(2), 213–234.

Bejarano, C. (2013). The Latina advantage: Gender, race, and political success. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Bishop, G. F., & Fisher, B. S. (2017). ‘Secret ballots’ and self-reports in an exit-poll experiment. Public Opinion Quarterly, 59(4), 568–588.

Blake, A. (2017). 21 Times Donald Trump has assured us he respects women. Washington Post, March 8. Retrieved June 1, 2017 from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2017/03/08/21-times-donald-trump-has-assured-us-he-respects-women/?utm_term=.4a30d4291c11.

Blumer, H. (1958). Race prejudice as a sense of group position. Pacific Sociological Review, 1, 3–7.

Bobo, L. D., & Massagli, M. P. (2001). Stereotyping and urban inequality. In A. O’Connor, C. Tilly, & L. D. Bobo (Eds.), Urban inequality: Evidence from four cities. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Bowler, S., Nicholson, S. P., & Segura, G. M. (2006). Earthquakes and aftershocks: Tracking partisan identification amid California’s changing political environment. American Journal of Political Science, 50(1), 146–159.

Braden, M. (1996). Women politicians in the media. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press.

Brooks, D. J. (2013). He runs, she runs: Why gender stereotypes do not harm women candidates. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Brooks, D. J., & Valentino, B. A. (2011). A war of one’s own: Understanding the gender gap in support for war. Public Opinion Quarterly, 75(2), 270–286.

Burden, B. C., Ono, Y., & Yamada, M. (2017). Reassessing public support for a female president. Journal of Politics, 79, 1073–1078.

Burns, S., Eberhardt, L., & Merolla, J. L. (2013). What’s the difference between a hockey mom and a pit bull? Presentations of Palin and gender stereotypes in the 2008 presidential election. Political Research Quarterly, 66, 687–701.

Burns, P., & Gimpel, J. G. (2000). Economic insecurity, prejudicial stereotypes, and public opinion on immigration policy. Political Science Quarterly, 115(2), 201–225.

Burrell, B. C. (1996). A woman’s place is in the house: Campaigning for Congress in the feminist era. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Bystrom, D. G., Banwart, M. C., Kaid, L. L., & Robertson, T. A. (2004). Gender and candidate communication: Videostyle, webstyle, newstyle. New York: Routledge.

Bystrom, D. G., Robertson, T. A., & Banwart, M. C. (2001). Framing the fight: An analysis of media coverage of female and male candidates in primary races for governor and U.S. Senate in 2000. The American Behavioral Scientist, 44, 1999–2013.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American voter. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Carli, L. L., & Eagly, A. H. (1999). Gender effects on social influence and emergent leadership. In G. N. Powell (Ed.), Handbook of gender & work (pp. 203–222). New York: SAGE Publications.

Carlin, D. B., & Winfrey, K. L. (2009). Have you come a long way, baby? Hillary Clinton, Sarah Palin, and sexism in 2008 campaign coverage. Communication Studies, 60(4), 326–343.

Carroll, S. J., & Schreiber, R. (1997). Media coverage of women in the 103rd Congress. In P. Norris (Ed.), Women, media and politics (pp. 131–148). New York: Oxford University Press.

Cassese, E. C., Barnes, T. D., & Branton, R. P. (2015). Racializing gender: Public opinion at the intersection. Politics & Gender, 11, 1–26.

CAWP. (2017). Center for American Women and Politics. State fact sheet. New Brunswick, NJ: Center for American Women and Politics.

Cho, W. K. T., Gimpel, J. G., & Wu, T. (2006). Clarifying the role of SES in political participation: Policy threat and Arab American mobilization. Journal of Politics, 68(4), 977–991.

Citrin, J., Green, D. P., & Sears, D. O. (1990). White reactions to Black candidates: When does race matter? The Public Opinion Quarterly, 54(1), 74–96.

Claassen, R. L. (2004). Political opinion and distinctiveness: The case of Hispanic ethnicity. Political Research Quarterly, 57(4), 609–620.

Collins, P. H. (1991). Black feminist thought: knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. New York: Routledge.

Conover, P. J., & Sapiro, V. (1993). Gender, feminist consciousness, and war. American Journal of Political Science, 37(4), 1079–1099.

Conroy, M. (2015). Masculinity, media, and the American presidency. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Conroy, M., Oliver, S., Breckenridge-Jackson, I., & Heldman, C. (2015). From Ferraro to Palin: Sexism in coverage of vice presidential candidates in old and new media. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 3(4), 573–591.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, pp. 139–167.

Cuddy, A. J. C., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2007). The BIAS map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(4), 631–648.

D’Angelo, C. (2016). Trump supporters are peddling disgustingly sexist anti-Hillary Clinton swag. Huffington Post, May 3. Retrived October 1, 2017 from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/deplorable-anti-clinton-merch-at-trump-rallies_us_572836e1e4b016f378936c22.

Darcy, R., Welch, S., & Clark, J. (1994). Women, elections, and representation (2nd ed.). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Davenport, L. D. (2016). Beyond black and white: Biracial attitudes in contemporary U.S. politics. American Political Science Review, 110(1), 52–67.

Dawson, M. C. (1994). Behind the mule: Race and class in African-American politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ditonto, T. (2017). A high bar or a double standard? Gender, competence, and information in political campaigns. Political Behavior, 39(2), 301–325.

Dolan, K. (1998). Voting for women in the ‘year of the woman’. American Journal of Political Science, 42(1), 272–293.

Dugger, K. (1988). Social location and gender-role attitudes: A comparison of black and white women. Gender and Society, 2(4), 425–448.

Dwyer, C. E., Stevens, D., Sullivan, J. L., & Allen, B. (2009). Racism, sexism, and candidate evaluations in the 2008 presidential election. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 9(1), 223–240.

Ferree, M. M., & Hess, B. B. (1987). Analyzing gender: A handbook of social science research. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Fiorina, M. P. (1981). Retrospective voting in American elections. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Fiske, S. T. (1993). Controlling other people: The impact of power on stereotyping. American Psychologist, 48(6), 621–628.

Fiske, S. T. (2011). Envy up, scorn down: How status divides us. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Foschi, M. (1996). Double standards in the evaluation of men and women. Social Psychology Quarterly, 59(3), 237–254.

Fox, R. L., & Lawless, J. L. (2004). Entering the arena? Gender and the decision to run for office. American Journal of Political Science, 48(2), 264–280.

Fox, R. L., & Lawless, J. L. (2005). To run or not to run for office: Explaining nascent political ambition. American Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 642–659.

Fox, R. L., & Oxley, Z. M. (2003). Gender stereotyping in state executive elections: Candidate selection and success. Journal of Politics, 65(3), 833–850.

Gilens, M. (1999). Why Americans hate welfare: Race, media, and the politics of antipoverty policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gilliam, F. D., Jr., & Iyengar, S. (2000). Prime suspects: The influence of local television news on the viewing public. American Journal of Political Science, 44(3), 560–573.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, 56(2), 109–118.

Gooley, R. L. (1989). The role of black women in social change. Western Journal of Black Studies, 13(4), 165–172.

Gurin, P. (1985). Women’s gender consciousness. Public Opinion Quarterly, 49(2), 143–163.

Gurin, P., Hatchett, S., & Gurin, G. (1980). Stratum identification and consciousness. Social Psychology Quarterly, 43(1), 33–47.

Han, L. C., & Heldman, C. (2007). Rethinking madam president: Are we ready for a woman in the White House? Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Harris-Perry, M. V. (2011). Sister citizen: Shame, stereotypes, and black women in America. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Heimer, K. (2007). U.S. media’s depictions of women candidates undermines electability. In A. Hiber (Ed.), Is the United States ready for a minority president? Detroit: Greenhaven Press.

Heldman, C., Carroll, S. J., & Olson, S. (2005). ‘She brought only a skirt’: Print media coverage of Elizabeth Dole’s bid for the Republican nomination. Political Communication, 22(3), 315–335.

Heldman, C., & Wade, L. (2011). Sexualizing Sarah Palin: The social and political context of the sexual objectification of female candidates. Sex Roles, 65(3), 156–164.

Hellevik, O. (2009). Linear versus logistic regression when the dependent variable is a dichotomy. Quality & Quantity, 43, 59–74.

Herek, G. M. (2002). Gender gaps in public opinion about lesbians and gay men. Public Opinion Quarterly, 66(1), 40–66.

Holman, M., Merolla, J. L., & Zechmeister, E. J. (2011). Sex, stereotypes, and security: A study of the effects of terrorist threat on assessments of female leadership. Journal of Women, Politics and Policy, 32(3), 173–192.

hooks, b. (1981). Ain’t I a woman?: Black women and feminism. Boston: South End Press.

Huber, G. A., & Arceneaux, K. (2007). Identifying the persuasive effects of presidential advertising. American Journal of Political Science, 51(4), 961–981.

Huddy, L. (1994). The political significance of voters’ gender stereotypes. In M. X. Delli Carpini, L. Huddy, & R. Y. Shapiro (Eds.), Research in micropolitics: New directions in political psychology (pp. 159–193). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Huddy, L., & Carey, T. E., Jr. (2009). Group politics redux: Race and gender in the 2008 Democratic presidential primaries. Politics & Gender, 5(1), 81–96.

Huddy, L., & Feldman, S. (2009). On assessing the political effects of racial prejudice. Annual Review of Political Science, 12, 423–447.

Huddy, L., & Terkildsen, N. (1993). Gender stereotypes and the perception of male and female candidates. American Journal of Political Science, 37(1), 119–147.

Hunter, A. G., & Sellers, S. L. (1998). Feminist attitudes among African American women and men. Violence Against Women, 12(1), 81–99.

Hyde, J. S. (2005). The gender similarities hypothesis. American Psychologist, 60(6), 581–592.

Iyengar, S., & Kinder, D. R. (1987). News that matters: Television & American opinion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Iyengar, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and loathing across party lines: New evidence on group polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 690–707.

Jackman, M. R. (1994). The velvet glove: Paternalism and conflict in gender, class and race relations. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Jost, J. T., & Banaji, M. R. (1994). The role of stereotyping in system-justification and the production of false-consciousness. British Journal of Social Psychology, 33, 1–27.

Junn, J. (2017). The Trump majority: White womanhood and the making of female voters in the United States. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 5(2), 343–352.

Kahn, K. F. (1992). Does being male help? An investigation of the effects of candidate gender and campaign coverage on evaluations of U.S. Senate candidates. The Journal of Politics, 54(2), 497–517.

Kahn, K. F. (1994a). Does gender make a difference? An experimental examination of sex stereotypes and press patterns in statewide campaigns. American Journal of Political Science, 38(1), 162–195.

Kahn, K. F. (1994b). The distorted mirror: Press coverage of women candidates for statewide office. The Journal of Politics, 56(1), 154–173.

Kahn, K. F. (1996). The political consequences of being a woman: How stereotypes influence the conduct and consequences of political campaigns. New York: Columbia University Press.

Kahn, K. F., & Goldenberg, E. N. (1991). Women candidates in the news: An examination of gender differences in U.S. Senate campaign coverage. Public Opinion Quarterly, 55(2), 180–199.

Kalkan, K. O., Layman, G. C., & Uslaner, E. M. (2009). ‘Bands of others’? Attitudes toward Muslims in contemporary American society. The Journal of Politics, 71(3), 847–862.

Kane, E. (1992). Race, gender, and attitudes toward gender stratification. Social Psychology Quarterly, 55(3), 311–320.

Katz, J. (2016). Man enough?: Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton, and the politics of presidential masculinity. Northampton, MA: Interlink Publishing.

Kaufmann, K. M. (2002). Culture wars, secular realignment, and the gender gap in party identification. Political Behavior, 24(3), 283–307.

Kaufmann, K. M., & Petrocik, J. R. (1999). The changing politics of American men: Understanding the sources of the gender gap. American Journal of Political Science, 3, 864–887.

Kerber, L. K. (1988). Separate spheres, female worlds, woman’s place: The rhetoric of women’s history. The Journal of American History, 75(1), 9–39.

Koch, J. W. (1999). Candidate gender and assessments of Senate candidates. Social Science Quarterly, 80(1), 84–96.

Kolko, J. (2016). ‘Normal America’ is not a small town of white people. FiveThirtyEight, April 28. Retrived January 11, 2018 from https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/normal-america-is-not-a-small-town-of-white-people/.

Krogstad, J. M., Lopez, M. H., López, G., Passel, J. S., Patten, E. (2016). Millennials make up almost half of Latino eligible voters in 2016. Pew Research Center, January, 19. Retrived June 22, 2016 from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2016/01/19/millennials-make-up-almost-half-of-latino-eligible-voters-in-2016/.

Lawless, J. L. (2004). Women, war, and winning elections: Gender stereotyping in the post-September 11th era. Political Research Quarterly, 57(3), 479–490.

Lawless, J. L. (2009). Sexism and gender bias in election 2008: A more complex path for women in politics. Politics & Gender, 5(1), 70–80.

Lawless, J. L., & Pearson, K. (2008). The primary reason for women’s underrepresentation? Reevaluating the conventional wisdom. Journal of Politics, 70(1), 67–82.

Lawrence, R. G., & Rose, M. (2010). Hillary Clinton’s race for the White House: Gender politics and the media on the campaign trail. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Leighley, J. E., & Vedlitz, A. (1999). Race, ethnicity, and political participation: Competing models and contrasting explanations. Journal of Politics, 61(4), 1092–1114.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., Tien, C., & Nadeau, R. (2010). Obama’s missed landslide: A racial cost. PS: Political Science & Politics, 43(1), 69–76.

Liang, C. T. H., Salcedo, J., & Miller, H. A. (2011). Perceived racism, masculinity ideologies, and gender role conflict among Latino men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 12(3), 201–215.

Lien, P. (1998). Does the gender gap in political attitudes and behavior vary across racial groups? Political Research Quarterly, 54(4), 869–894.

Lupia, A. (1994). Shortcuts versus encyclopedias: Information and voting behavior in California insurance reform elections. American Political Science Review, 88(1), 63–76.

Mansfield, E. D., Mutz, D. C., & Silver, L. R. (2015). Men, women, trade, and free markets. International Studies Quarterly, 59(2), 303–315.

Masuoka, N., & Junn, J. (2013). The politics of belonging: Race, public opinion and immigration. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McConnaughy, C. M., & White, I. K. (2011). Racial politics complicated: The work of gendered race cues in American politics. Working Paper, Department of Political Science, Ohio State University.

McDermott, M. L. (1997). Voting cues in low-information elections: Candidate gender as a social information variable in contemporary United States elections. American Journal of Political Science, 41(1), 270–283.

McDermott, M. L. (1998). Race and gender cues in low-information elections. Political Research Quarterly, 51(4), 895–918.

Mendelberg, T. (1997). Executing Hortons: Racial crime in the 1988 presidential campaign. Public Opinion Quarterly, 61, 134–157.

Mendelberg, T. (2001). The race card: Campaign strategy, implicit messages, and the norm of equality. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Mendelberg, T. (2008). Racial priming revived. Perspectives on Politics, 6(1), 109–123.

Miller, M. K., Peake, J. S., & Boulton, B. A. (2010). Testing the Saturday Night Live hypothesis: Fairness and bias in newspaper coverage of Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign. Politics & Gender, 6(2), 169–198.

Miller, W. E., & Shanks, J. M. (1996). The New American voter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Norrander, B. (1999). The evolution of the gender gap. Public Opinion Quarterly, 63, 566–576.

Oliver, J. E., & Ha, S. E. (2007). Vote choice in suburban elections. American Political Science Review, 101(3), 393–408.

Pantoja, A. D., Ramirez, R., & Segura, G. M. (2001). Citizens by choice, voters by necessity: Patterns in political mobilization by naturalized Latinos. Political Research Quarterly, 54(4), 729–750.

Paul, D., & Smith, J. L. (2008). Subtle sexism? Examining vote preferences when women run against men for the presidency. Journal of Women, Politics and Policy, 29(4), 451–476.

Pérez, E. O. (2015). Ricochet: How elite discourse politicizes racial and ethnic identities. Political Behavior, 37(1), 155–180.

Pérez, E. O., & Hetherington, M. J. (2014). Authoritarianism in black and white: Testing the cross-racial validity of the child rearing scale. Political Analysis, 22(3), 398–412.

Philpot, T. S., & Walton, H., Jr. (2007). One of our own: Black female candidates and the voters who support them. American Journal of Political Science, 51(1), 49–62.

Pickett, C. L., & Brewer, M. B. (2001). Assimilation and differentiation needs as motivational determinants of perceived in-group and out-group homogeneity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 37, 341–348.

Reeves, K. (1997). Voting hopes or fears? White voters, black candidates and racial politics in America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ridgeway, C. (2011). Framed by gender: How gender inequality persists in the modern world. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ridgeway, C. L., & Correll, S. J. (2004). Unpacking the gender system: A theoretical perspective on gender beliefs and social relations. Gender and Society, 18(4), 510–531.

Risman, B. A. (1998). Gender vertigo: American families in transition. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Rosenwasser, S. M., & Seale, J. (1988). Attitudes toward a hypothetical male or female presidential candidate: A research note. Political Psychology, 9(4), 591–598.

Rudman, L. A. (1998). Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: The costs and benefits of counter-stereotypical impression management. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 629–645.

Rudman, L. A., & Glick, P. (2001). Prescriptive gender stereotypes and backlash toward agentic women. Journal of Social Issues, 57(4), 743–762.

Samson, F. L., & Bobo, L. D. (2014). Ethno-racial attitudes and social inequality. In J. McLeod, E. Lawler, & M. Schwalbe (Eds.), Handbook of the social psychology of inequality (pp. 515–545). New York: Springer.

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2002). Gender stereotypes and vote choice. American Journal of Political Science, 46(1), 20–34.

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2003a). Gender-related political knowledge and the descriptive representation of women. Political Behavior, 25(4), 367–388.

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2003b). Political knowledge and gender stereotypes. American Political Research, 31(6), 575–594.

Sapiro, V. (1981). If U.S. Senator Baker were a woman: An experimental study of candidate images. Political Psychology, 3, 61–83.

Sapiro, V. (1983). The political integration of women: Roles, socialization, and politics. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Schlesinger, M., & Heldman, C. (2001). Gender gap or gender gaps? New perspectives on support for government action and policies. Journal of Politics, 63(1), 59–92.

Schneider, M. C., & Bos, A. L. (2014). Measuring stereotypes of female politicians. Political Psychology, 35(2), 245–266.

Sears, D. O. (1988). Symbolic racism. In P. A. Katz & D. A. Taylor (Eds.), Eliminating racism: Profiles in controversy (pp. 53–84). New York: Plenum Publishing.

Sears, D. O., Hensler, C. P., & Speer, L. K. (1979). Whites’ opposition to ‘busing’: Self-interest or symbolic politics? American Political Science Review, 73(2), 369–384.

Segura, G. M., & Valenzuela, A. A. (2010). Hopes, tropes, and dopes: Hispanic and white racial animus in the 2008 election. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 40(3), 497–514.

Seltzer, R. A., Newman, J., & Leighton, M. V. (1997). Sex as a political variable. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Shapiro, R. Y., & Mahajan, H. (1986). Gender differences in policy preferences: A summary of trends from the 1960s to 1980s. Public Opinion Quarterly, 50(1), 42–61.

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sigelman, L., & Welch, S. (1984). Race, gender, and opinion toward black and female presidential candidates. Public Opinion Quarterly, 48(2), 467–475.

Simien, E. M. (2004). Gender differences in attitudes toward black feminism among African Americans. Political Science Quarterly, 119(2), 315–338.

Smith, E. R. A. N. & Fox, R. L. (2001). A research note: The electoral fortunes of women candidates for Congress. Political Research Quarterly, 54, 205–221.

Snyder-Hall, R. C. (2008). The ideology of wifely submission: A challenge for feminism? Politics & Gender, 4, 563–586.

Stein, K. F. (2009). The cleavage commotion: How the press covered Senator Clinton’s campaign. In T. F. Sheckels (Ed.), Cracked but not shattered: Hillary Rodham Clinton’s unsuccessful campaign for the presidency (pp. 173–187). Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Strolovitch, D. Z., Wong, J. S., & Proctor, A. (2017). A possessive investment in white heteropatriarchy? The 2016 election and the politics of race, gender, and sexuality. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 5(2), 353–363.

Swim, J., Borgida, E., Maruyama, G., & Myers, D. G. (1989). Joan McKay versus John McKay: Do gender stereotypes bias evaluations? Psychological Bulletin, 3, 409–429.

Swim, J. K., Aikin, K. J., Hall, W. S., & Hunter, B. A. (1995). Sexism and racism: Old-fashioned and modern prejudices. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(2), 199–214.

Tate, K. (1994). From protest to politics: The new black voters in American elections. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Tate, K. (2003). Black faces in the mirror: African Americans and their representatives in the U.S. Congress. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Tesler, M. (2013). The return of old-fashioned racism to white Americans’ partisan preferences in the early Obama era. Journal of Politics, 75(1), 110–123.

Tesler, M., & Sears, D. O. (2010). Obama’s race: The 2008 election and the dream of a post-racial America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Traugott, M. W., & Price, V. (1992). Exit polls in the 1989 Virginia gubernatorial race: Where did they go wrong? Public Opinion Quarterly, 56(2), 245–253.

Tuch, S. A., & Hughes, M. (2011). Whites’ racial policy attitudes in the twenty–first century: The continuing significance of racial resentment. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 634(1), 134–152.

Unnever, J. D., & Cullen, F. T. (2007). The racial divide in support for the death penalty: Does white racism matter? Social Forces, 85(3), 1281–1301.

Valentino, N. A., & Sears, D. O. (2005). Old times there are not forgotten: Race and partisan realignment in the contemporary South. American Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 672–688.

Varon, E. R. (1998). We mean to be counted: White women and politics in antebellum Virginia. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press.

Wayne, C., Oceno, M., Valentino, N. (2016). “How sexism drives support for Donald Trump.” Washington Post, October 23. Retrived October 1, 2017 from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/10/23/how-sexism-drives-support-for-donald-trump/?utm_term=.afd6b1fd0418.

Weir, S. J. (1996). Women as governors: State executive leadership with a feminist face. In L. L. Duke (Ed.), Women in politics: Outsiders or insiders (pp. 3143–3259). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Welch, S., & Sigelman, L. (1982). Changes in public attitudes toward women in politics. Social Science Quarterly, 63(2), 312–322.

White, A. (2016). When threat mobilizes: Immigration enforcement and Latino voter turnout. Political Behavior, 38, 355–382.

Winter, N. J. G. (2005). Framing gender: Political rhetoric, gender schemas, and public opinion on health care reform. Politics & Gender, 1(3), 453–480.

Winter, N. J. G. (2006). Beyond welfare: Framing and the racialization of white opinion on social security. American Journal of Political Science, 50(2), 400–420.

Winter, N. J. G. (2008). Dangerous frames: How ideas about race and gender shape public opinion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Woodall, G. S., & Fridkin, K. L. (2007). Shaping women’s chances: Stereotypes and the media. In L. C. Han & C. Heldman (Eds.), Rethinking madam president: Are we ready for a woman in the White House? Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Acknowledgements

We thank Matt Barreto, Caroline Heldman, Nazita Lajevardi, Hannah Walker, and the participants of the UCLA May 2017 mini-conference for their thoughtful and instructive comments. We are grateful to David Rudd Ross for his careful reading. Thank you to Matt Barreto and Loren Collingwood for their efforts and organization. We greatly appreciate Skip Lupia’s helpful advice on training students to interview voters. We are indebted to Keith Gaddie and the College of Arts & Sciences for their support in developing the Community Engagement + Experiments Lab at the University of Oklahoma. We thank Joy Pendley for her leadership with CEEL. We are grateful to Doug Sanderson and the Oklahoma County Election Board for their willingness to work with researchers. Thanks to Alisa Hicklin Fryar and Tyler Johnson for their sage advice. Finally, thank you to the more than sixty undergraduate and graduate students who spent their day surveying voters and to Cathy Brister, Katelyn Burks, David Rudd Ross, and Jamie Vaughn for their field support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors are listed alphabetically.

Data and replication files are available at http://dx.doi.org/10.7910/DVN/XTJRQN

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bracic, A., Israel-Trummel, M. & Shortle, A.F. Is Sexism for White People? Gender Stereotypes, Race, and the 2016 Presidential Election. Polit Behav 41, 281–307 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9446-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9446-8