Abstract

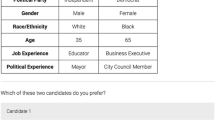

To what extent do voters grasp “what goes with what” among key political objects as they attempt to understand the choices they face at the ballot box? Is recognition of these associations limited to only the most informed citizens? We design a novel conjoint classification experiment that minimizes partisan boosting and allows for the relative comparison of attribute effect when mapping voter associative networks, the cluster of attributes linked to parties and ideological labels. We ask respondents to ‘guess’ the party or ideology of hypothetical candidates with fully randomized issue priorities and biographical details. There is remarkable agreement among both high- and low-knowledge voters in linking issues to each party and ideology, suggesting this minimalist form of associative competence is more widely held in the mass public than perhaps previously thought. We find less agreement about biographical traits, which appear to pose greater informational challenges for voters. Notably, nearly identical issue priorities and traits are associated with party and ideology, indicating these two dimensions are largely fused in the minds of today’s American voters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We conceive of a party or ideological label as a central node in this network, and we measure the strength of all connections with that node. To our knowledge, the only existing study that seeks to measure party-issue associations is Walgrave et al. (2012). The authors directly survey Belgian respondents about which issues they associate with particular parties. Unfortunately, they do not address how respondents’ partisan affiliations can color their responses about party associations, particularly relevant in the U.S.

In addition to the obvious conceptual differences between parties and ideologies, he also finds variation in strength of affiliations between them. It is for this reason we assess the relative strength of partisan and ideological associations, as we might expect that ideological thinking is not as deeply rooted and connected to other political information.

A pervasive problem in past research is that PID can significantly distort measures of party stereotypes. One standard question drawn from work on issue ownership, asks voters which party they think would “do a better job handling” a number of specific issues (Petrocik 1996). Responses are usually interpreted as tapping unbiased evaluations of the parties’ abilities, though an obvious concern is that many partisans will (expressively or genuinely) state they trust their own party to handle every issue (Egan 2013; Goggin and Theodoridis 2017). We illustrate this partisan bias in Fig. I in the Appendix, using the standard issue ownership question from a poll in 2010. Here partisans’ responses have polarized, canceling each other out so that measures depend almost entirely on relatively uninformed independents. We are not the first to address this concern. Walgrave et al. Walgrave et al. (2012) directly ask voters which issues come to mind when thinking about parties in Belgium, though this wording could prime partisan attitudes as well.

This task could easily be adapted to accommodate more than two parties. Researchers could ask respondents to indicate which party is more appropriate, with only two of the total parties displayed, or could choose amongst the full set.

A standard assumption in conjoint designs is no interactions exist between attributes, though this can be relaxed to exclude more complex effects. We rule out virtually all two-way interactions empirically, including all interactions between issues, gender and the other biographical traits. A second assumption is evaluation stability, so there are no profile-order effects (Hainmueller et al. 2014). Statistical power is obtained under these assumptions by having respondents evaluate multiple hypothetical candidates. Here, paired comparison would be unwieldy for respondents, since unlike the paired choices in other conjoint tasks (e.g., selecting which candidate to support), there are few real-world analogues for guessing which candidate is more Democratic or Republican.

Following Egan (2013), we include issue priorities, not positions. This provides a harder test of party associations, and indicates that even minimal cues can prime partisanship.

We selected factors that provide a reasonably detailed candidate description, based on characteristics considered relevant to candidates’ electoral or policy performance. A notable omission is race. We excluded race information for fear that the anticipated massive Democratic effect for black candidates would mask associations on other dimensions.

Each candidate had a 1st Issue Priority, a 2nd Issue Priority, and a 3rd Issue Priority, with these issues sampled without replacement from the list in Table I.

The CCES is fielded online by YouGov in the weeks prior to and just after Election Day. In keeping with the suggestions of Miratrix et al. (2018) the analyses presented here do not use sampling weights.

Roughly 48% of respondents identified as Democrats (including leaners), 14% as pure independents, and 33% as Republicans (including leaners).

An alternative way to present these effects is by estimating how the presence of each factor level changes the probability that a given respondent assigns the target candidate the “correct” party. In order to assess this, the sample is split and used to generated predicted probabilities of the overall candidate profile being a Democrat (0) or Republican (1) in the other half of the sample. Once recombined, we can then change the dependent variable to a measure of “correctness” where we assess if respondents correctly guessed “Democrat” for profiles with a predicted value below 0.4 and “Republican” for profile with a predicted value above 0.6. We exclude the 0.4–0.6 range as these profiles would be harder to predict. The correct prediction rate is 64.0% for the full sample and 70.6% when profiles in the 0.4–0.6 range are excluded. If we excluded all profiles in the 0.2–0.8 range, thus leaving only the most clear-cut Democratic and Republican profiles, we see the correct prediction rate improve to 80.7%. These analyses for both partisanship and ideology can be seen in Figs. VIII, IX, X, and XI in the Appendix. Table II in the Appendix displays the average “correctness” for all factor levels when 0.4–0.6 profiles are excluded. Notably, counter-stereotypical attributes relative to the party/ideology of a profile produce substantially lower rates of correctness.

Separating out issues by their priority produces virtually identical results. Issues were stronger signals (more significant results and smaller confidence intervals) when they were higher priority, but the direction and relative magnitude of the effects were identical across the three positions. For clarity of presentation, we collapse across positions here.

We exclude pure independents for clarity. Inferences by independents fall between that for Democrats and Republicans, but with wider confidence intervals. If one wishes to model these interactions with respondents’ partisanship formally, Table IV displays this model with issues.

An alternative way of assessing knowledge would be to measure the “correctness” of the guess itself, particular if a respondent is sure of the answer. Following the procedure to predict the party of a given profile described in a previous footnote, Figs. XII and XIV in the Appendix display these differences for partisanship and ideology, respectively. As expected, respondents who are “correct” and more sure of their answers generally exhibit larger effect sizes, similar to the results for this measure of political knowledge. Across all candidate profiles, respondents with high knowledge (median split) correctly guessed 68.1% of the profiles, while low knowledge respondents correctly guessed 60.2%.

If one wishes to model the interaction with political knowledge formally, Table V displays these results for issues.

In line with the analyses of “correctness” described previously, we also see that even low knowledge respondents generally correctly predict the partisanship of the candidate profile. For candidates in the 0.4-0.6 range on the 0-1 partisanship scale, respondents with higher-than-median political knowledge correctly guess the party 75.8% of the time, while respondents with low knowledge still correctly guess the party 65.6% of the time.

As a general point, it is not clear that respondent guesses should necessarily correspond in magnitude to the actual distributions of attributes observed among candidates. There could be critical densities at which virtually all voters are capable of seeing an association, so that respondents overestimate the accordance between parties and attributes relative to reality (e.g., Ahler and Sood 2018). If real candidates from one party possessed a given trait 75% of the time, for instance, it could be reasonable for voters to always guess that party when presented with that trait. Consequently, we look for the concordance between direction (and not magnitude) of party guesses and candidate features. If we wish to examine magnitude more closely, we can examine the raw proportion of guesses for each party, given a particular factor level. Table III in the Appendix displays the proportion of guesses that a candidate was Republican. From this, we can more easily assess how much respondents pick up on these differences. While the bulk of the proportions are near 0.5, some attributes, particularly issues, are particularly powerful signals of the party of a candidate. Future work could incorporate other sources of data (such as VoteSmart’s National Political Awareness Test) and accordingly constrained conjoint design to better make magnitude comparisons. Such analyses will, however, remain limited by gaps in available data and the presence of empty cells in the true distributions of candidate characteristics.

Candidates with missing information are included in all reported percentages since such omission could be strategic and thus informative.

Candidates reported 3.7 occupations on average to Project VoteSmart, and these analyses report the percentage of candidates listing an occupation in that category, even if it was not their most recent occupation.

The seemingly overall negative trend in evaluations among many of the issues is simply a result of the omitted issue priority being the near universal “strengthening the economy”, as that is viewed as more positive than the bulk of issue priorities.

We cannot entirely separate partisanship from the effect of the issue priority itself, for example, when respondents view the issue positively or negatively independent of party.

The figure looks nearly identical stratifying by self-reported ideology rather than partisanship. However, due to the larger number of respondents that choose “moderate” versus the number that view themselves as “pure independents”, the confidence intervals are substantially wider for the “liberal” and “conservative” respondent categories. We omit independents merely for the clarity of the figure, as previously noted.

Following other work on candidate recruitment, this finding could indicate that Republican voters are less willing to support female candidates (Lawless and Pearson 2008; Preece and Stoddard 2015). Yet, we cannot preclude that Republican identifiers negatively evaluate women in our experiment because they assume they are probably Democrats.

References

Abramowitz, Al I. (2011). The disappearing center: Engaged citizens, polarization, and American democracy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Abramowitz, A. I. (2018). The great alignment: Race, party transformation, and the rise of Donald Trump. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Achen, C. H., & Bartels, L. M. (2016). Democracy for realists: Why elections do not produce responsive government. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ahler, D. J., & Sood, G. (2018). The parties in our heads: Misperceptions about party composition and their consequences. The Journal of Politics, 80(3), 964–981.

Ansolabehere, S. (2015). Cooperative Congressional Election Study, 2014: Common Content. [Computer File] Release 1: February 2015.

Ansolabehere, S., & Jones, P. E. (2010). Constituents’ responses to congressional roll-call voting. American Journal of Political Science, 54(3), 583–597.

Arceneaux, K. (2009). Can partisan cues diminish democratic accountability? Political Behavior, 30(2), 139–160.

Arceneaux, K., & Johnson, M. (2013). Changing minds or changing channels: Partisan news in an age of choice. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

Arceneaux, K., & Vander Wielen, R. J. (2017). Taming intuition: How reflection minimizes partisan reasoning and promotes democratic accountability. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bartels, L. M. (1996). Uninformed votes: Information effects in presidential elections. American Journal of Political Science, 40(1), 194–230.

Berinsky, A. J. (2015). Rumors and health care reform: Experiments in political misinformation. British Journal of Political Science, 47(2), 241–262.

Bishop, B. (2008). The big sort: Why the clustering of like-minded America is tearing us apart. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Bolsen, T., Druckman, J. N., & Cook, F. L. (2014). The influence of partisan motivated reasoning on public opinion. Political Behavior, 36(2), 235–262.

Brady, H. E., & Sniderman, P. M. (1985). Attitude attribution: A group basis for political reasoning. American Political Science Review, 79(4), 1061–1078.

Bullock, J. G., Gerber, A. S., Hill, S. J., & Huber, G. A. (2015). Partisan bias in factual beliefs about politics. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 10(2), 519–578.

Carsey, T. M., & Layman, G. C. (2006). Changing sides or changing minds? Party identification and policy preferences in the American electorate. American Journal of Political Science, 50(2), 464–477.

Conover, P. J., & Feldman, S. (1984). How people organize the political world: A schematic model. American Journal of Political Science, 28(1), 95–126.

Converse, P. E. (1964). The nature of belief systems in mass publics. Critical Review, 18(1), 1–74.

Coronel, J. C., Federmeier, K. D., & Gonsalves, B. D. (2014). Event-eelated potential evidence suggesting voters remember political events that never happened. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9(3), 358–366.

Dafoe, A., Zhang, B., & Caughey, D. (2018). “Information Equivalence in Survey Experiments.” Political Analysis.

Damore, D. F. (2004). The dynamics of issue ownership in presidential campaigns. Political Research Quarterly, 57(3), 391–397.

Dancey, L., & Sheagley, G. (2013). Heuristics behaving badly: Party cues and voter knowledge. American Journal of Political Science, 57(2), 312–325.

Dancey, L., & Sheagley, G. (2016). Inferences made easy: Partisan voting in congress, voter knowledge, and senator approval. American Politics Research, 44, 844–874.

Egan, P. J. (2013). Partisan priorities: How issue ownership drives and distorts American politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Feldman, S., & Conover, P. J. (1983). Candidates, issues, and voters: The role of inference in political perception. Journal of Politics, 45, 810–839.

Fiorina, M. P. (1980). The decline of collective responsibility in American politics. Daedalus, 109(3), 25–45.

Freeder Sean, L., Gabriel, S., & Turney, S. (2019). The importance of knowing ’What Goes With What’: Reinterpreting the evidence on attitude stability. Journal of Politics, 81(1), 274–290.

Goggin, S. N. (2016). Personal politicians: Biography and its role in the minds of voters. PhD thesis, University of California, Berkeley.

Goggin, S., & Theodoridis, A. G. (2018). Seeing red (or blue): How party identity colors political cognition. The Forum, 16(1), 81–95.

Goggin, S. N., & Theodoridis, A. G. (2017). Disputed ownership: Parties, issues, and traits in the minds of voters. Political Behavior, 39, 675–702.

Hainmueller, J., & Hopkins, D. J. (2015). The hidden American immigration consensus: A conjoint analysis of attitudes toward immigrants. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 529–548.

Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J., & Yamamoto, T. (2014). Causal inference in conjoint analysis: Understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Political Analysis, 22(1), 1–30.

Hartman, T. K., & Newmark, A. J. (2012). Motivated reasoning, political sophistication, and associations between President Obama and Islam. Political Science and Politics, 45(3), 449–455.

Hayes, D. (2005). Candidate qualities through a partisan lens: A theory of trait ownership. American Journal of Political Science, 49(4), 908–923.

Hayes, D. (2010). Trait voting in US senate elections. American Politics Research, 38(6), 1102–1129.

Heit, E., & Nicholson, S. P. (2016). Missing the Party: Political categorization and reasoning in the absence of party labels. Topics in Cognitive Science, 8(3), 697–714.

Henderson, J.A. (2015). 2014 Yale University Cooperative Congressional Election Study Module. [Computer File].

Henderson, J.A. (2018). Blind guessing? voter competence about Partisan messaging. Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association.

Henderson, J. A., & Theodoridis, A. G. (2017). Seeing spots: An experimental examination of voter appetite for partisan and negative campaign ads. Political Behavior, 40(4), 965–987.

Hetherington, M. J., & Weiler, J. D. (2009). Authoritarianism and polarization in American politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hetherington, M. J., & Weiler, J. D. (2018). Prius or pickup?: How the answers to four simple questions explain America’s great divide. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Holian, D. B. (2004). He’s stealing my issues! Clinton’s crime rhetoric and the dynamics of issue ownership. Political Behavior, 26(2), 95–124.

Kinder, D. R., & Kalmoe, N. P. (2017). Neither liberal nor conservative: Ideological innocence in the American public. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Klar, S. (2013). The influence of competing identity primes on political preferences. The Journal of Politics, 75(4), 1108–1124.

Klar, S. (2014). A multidimensional study of ideological preferences and priorities among the American public. Public Opinion Quarterly, 78(S1), 344–359.

Kuklinski, J. H., Quirk, P. J., Jerit, J., Schwieder, D., & Rich, R. F. (2000). Misinformation and the currency of democratic citizenship. Journal of Politics, 62(3), 790–816.

Lawless, J. L., & Pearson, K. (2008). The primary reason for women’s underrepresentation? Reevaluating the conventional wisdom. Journal of Politics, 70(1), 67–82.

Lee, F. E. (2009). Beyond ideology: Politics, principles, and partisanship in the U.S. senate. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Levendusky, M. (2009). The partisan sort: How liberals became democrats and conservatives became republicans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Levendusky, M. S. (2010). Clearer cues, more consistent voters: A benefit of elite polarization. Political Behavior, 32(1), 111–131.

Lodge, M., & Hamill, R. (1986). A partisan schema for political information processing. The American Political Science Review, 80(2), 505–520.

Lupia, A., & McCubbins, M. D. (1998). The democratic dilemma: Can citizens learn what they need to know?. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Malka, A., & Lelkes, Y. (2010). More than ideology: Conservative-liberal identity and receptivity to political cues. Social Justice Research, 23(2), 156–188.

Mason, L. (2015). I disrespectfully agree: The differential effects of partisan sorting on social and issue polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(1), 128–145.

Mason, L. (2016). A cross-cutting calm: How social sorting drives affective polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(S1), 351–377.

Mason, L. (2018). Uncivil agreement: How politics became our identity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mason, L., & Wronski, J. (2018). One tribe to bind them all: How our social group attachments strengthen partisanship. Political Psychology, 39(S1), 257–277.

Miratrix, L. W., Sekhon, J. S., Theodoridis, A. G., & Campos, L. F. (2018). Worth weighting? How to think about and use weights in survey experiments. Political Analysis, 26(3), 275–291.

Nicholson, S. P. (2011). Dominating cues and the limits of elite influence. Journal of Politics, 73(4), 1165–1177.

Perrig, W. J. (2001). Implicit memory, cognitive psychology. In N. J. Smelser & P. B. Baltes (Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (pp. 7241–7245). Oxford: Pergamon.

Petrocik, J. R. (1996). Issue ownership in presidential elections, with a 1980 case study. American Journal of Political Science, 40(3), 825–850.

Preece, J. R., & Stoddard, O. B. (2015). Does the message matter? A field experiment on political party recruitment. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 2(1), 1–10.

Rahn, W. M. (1993). The role of partisan stereotypes in information processing about political candidates. American Journal of Political Science, 37(2), 472–496.

Rothschild, J.E., Howat, A.J., Shafranek, R.M., & Busby, E.C. (2018). Pigeonholing partisans: Stereotypes of party supporters and partisan polarization. Political Behavior.

Sides, J. (2006). The Origins of campaign agendas. British Journal of Political Science, 36(3), 407.

Sniderman, P. M., & Stiglitz, E. H. (2012). The reputational premium: A theory of party identification and policy reasoning. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Snyder, Jr., J. M., & Ting, M. M. (2002). An informational rationale for political parties. American Journal of Political Science, 46(1), 90–110.

Theodoridis, A.G. (2012). Party identity in political cognition. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of California, Berkeley.

Theodoridis, A. G. (2013). Implicit political identity. Political Science and Politics, 46(3), 545–549.

Theodoridis, A.G. (2015). 2014 University of California, Merced Cooperative Congressional Election Study Module. [Computer File].

Theodoridis, A. G. (2017). Me, myself, and (I),(D), or (R)? Partisanship and political cognition through the lens of implicit identity. The Journal of Politics, 79(4), 1253–1267.

Thomsen, D. M. (2015). Why so few (republican) women? Explaining the partisan imbalance of women in the US congress. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 40(2), 295–323.

Walgrave, S., Lefevere, J., & Tresch, A. (2012). The associative dimension of issue ownership. Public Opinion Quarterly, 1(1), 1–12.

Winter, N. J. G. (2010). Masculine republicans and feminine democrats: Gender and americans’ explicit and implicit images of the political parties. Political Behavior, 32(4), 587–618.

Woon, J., & Pope, J. C. (2008). Made in congress? Testing the electoral implications of party ideological brand names. Journal of Politics, 70(3), 823–836.

Zaller, J. (1992). The nature and origin of mass opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

For valuable comments we thank Doug Ahler, Henry Brady, Jack Citrin, Jacob Hacker, Greg Huber, Jeff Jenkins, Travis Johnston, Katherine Krimmel, Gabe Lenz, Steve Nicholson, Jas Sekhon, Eric Schickler, Kim Twist, and Rob Van Houweling, as well as workshop participants at the University of Virginia, Northwestern University and Syracuse University, and attendees at the CCES Sundance Conference and the ISPS Summer Workshop. All errors are our responsibility. This work was funded by generous research support from the University of California, Merced and Yale University, and supported by the National Science Foundation, Award #1430505. Replication materials are available here: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RDQZUM.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goggin, S.N., Henderson, J.A. & Theodoridis, A.G. What Goes with Red and Blue? Mapping Partisan and Ideological Associations in the Minds of Voters. Polit Behav 42, 985–1013 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-09525-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-09525-6