Abstract

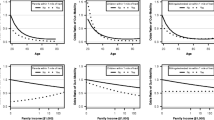

Residential mobility has substantial negative effects on voter turnout. However, existing studies have been unable to disentangle whether this is due to social costs, informational costs or convenience costs that are related to re-registration. This article analyzes the relevance of the different costs by studying the effect of moving and reassignment to a new polling station in an automatic registration context and using a register-based panel dataset with validated turnout for 2.1 million citizens. The negative effect of moving on turnout does not differ substantially depending on the distance moved from the old neighborhood and it does not matter if citizens change municipality. Thus, the disruption of social ties is the main explanation for the negative effect of moving on turnout. Furthermore, the timing of residential mobility is important as the effect on turnout declines quickly after settling down. This illustrates that large events in citizens’ everyday life close to Election Day can distract them from going to the polling station. Finally, residential mobility mostly affects the turnout of less educated citizens. Consequentially, residential mobility increases inequalities in voter participation, which can be viewed as a democratic problem.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Citizens who move to a new municipality within nine days before the election need to have registered their new address with the authorities to be able to vote in their new municipality. It is normal practice to register a new address ahead of changing residence, as it is the basis for a large number of public service provisions. Changing one’s address is done online and takes only a few minutes. In case citizens miss this date, they will be registered to vote in their old municipality.

Voters can cast an early vote up to 3 months ahead of the elections by going to a pre-election polling place (e.g. a library). Citizens’ cannot use mail-in voting. In the 2013-elections, 5.3 % of the votes were cast as early votes (Bhatti et al. 2014b). The early voters are included in the analysis and it does not make any substantial difference if the analysis is conducted without these voters.

In Denmark, voting lists are normally destroyed shortly after the election. However, in 2009 and 2013, all municipalities were allowed and encouraged to send the lists in digital form to a team of researchers. In 2009, 44 municipalities delivered the voter files for almost all of their citizens, and all municipalities delivered the information in 2013 (for a more detailed description, see Bhatti and Hansen 2010; Bhatti et al. 2014b).

The data are stored on servers at Statistics Denmark. Due to security and privacy reasons, the data cannot be made available on the Internet. Researchers interested in replicating the findings are welcome to visit and work under supervision. Also, a number of other researchers from Danish research institutions have access to the data and can be helpful if questions arise. Please ask the author for references.

One noteworthy exception is Squire et al. (1987), in which a part of the analysis is based on the Current Population Survey (CPS), a dataset containing residential mobility information at a monthly level for app. 115,000 citizens. Unfortunately, the same dataset contains a limited number of politically relevant variables, and the authors do not have access to validated turnout for the sample. Knack and White (2000) uses CPS data as well but does not present results at a more detailed level than whether citizens have changed residence within a year before the election.

One might object that moving entails a number of practical tasks that take away focus from the election, which the reassigned citizens do not have to cope with. While this point most likely is correct and is in line with the idea of a distraction effect, it is not really on target regarding this part of the analysis, as the timing of residential change is included as a control variable (cf. Table 1 in Appendix). The question of timing and the potential distraction effect is explored under the next heading.

Breaking the moving variable into the three residential groups that were used in the previous part of the analysis results in the same pattern as presented in Fig. 4 (as shown in the Online Resource Figure A.1).

References

Aldrich, J. H., Montgomery, J. M., & Wood, W. (2011). Turnout as a habit. Political Behavior, 33(4), 535–563.

Ansolabehere, S., Hersh, E., & Shepsle, K. (2012). Movers, stayers, and registration: Why age is correlated with registration in the U.S. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 7(4), 333–363.

Bhatti, Y. (2012). Distance and voting: Evidence from Danish municipalities. Scandinavian Political Studies, 35(2), 141–158.

Bhatti, Y., & Hansen, K. M. (2010). Valgdeltagelsen ved kommunalvalget 17. november 2009. Beskrivende analyser af valgdeltagelsen baseret på registerdata. Arbejdspapir Københavns Universitet, Institut for Statskundskab, 2010(3).

Bhatti, Y. & Hansen, K. M. 2013. The effect of co-residence on turnout. MPSA Annual Conference 2013. Chicago.

Bhatti, Y., Hansen, K. M., & Wass, H. (2012). The relationship between age and turnout: A roller-coaster ride. Electoral Studies, 31(3), 588–593.

Bhatti, Y., Dahlgaard, J. O., Hansen, J. H., & Hansen, K. M. (2014a). Kan man øge valgdeltagelsen? Analyse af mobiliseringstiltag ved kommunalvalget den 19. november 2013 København: Institut for Statskundskab, Københavns Universitet.

Bhatti, Y., Dahlgaard, J. O., Hansen, J. H., & Hansen, K. M. (2014b). Hvem stemte og hvem blev hjemme? Valgdeltagelsen ved kommunalvalget 19. november 2013. Beskrivende analyser af valgdeltagelsen baseret på registerdata. København: Institut for Statskundskab, Københavns Universitet

Bhatti, Y., Dahlgaard, J. O., Hansen, J. H., & Hansen, K. M. (2015). How voter mobilization from short text messages travels within households and families: Evidence from two nationwide field experiments. Midwest Political Science Association’s Annual Meeting 2015. Chicago.

Blais, A. (2000). To vote or not to vote?: The merits and limits of rational choice theory. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Blais, A. (2006). What affects voter turnout? Annual Review of Political Science, 9, 111–125.

Blais, A., Young, R., & Lapp, M. (2000). The calculus of voting: An empirical test. European Journal of Political Research, 37(2), 181–201.

Bowers, J. (2004). Does moving disrupt campaign activity? Political Psychology, 25(4), 525–543.

Brady, H., & Mcnulty, J. (2011). Turning out to vote: The costs of finding and getting to the polling place. American Political Science Review, 105(1), 115–134.

Brady, H. E., Verba, S., & Schlozman, K. L. (1995). Beyond SES: A resource model of political participation. American Political Science Review, 89(02), 271–294.

Coppock, A., & Green, D. P. (2015). Is voting habit forming? New evidence from experiments and regression discontinuities. American Journal of Political Science. doi:10.1111/ajps.12210.

Cutts, D., Fieldhouse, E., & John, P. (2009). Is voting habit forming? The longitudinal impact of a GOTV campaign in the UK. Journal of Elections Public Opinion and Parties, 19(3), 251–263.

Dahl, R. A. (1989). Democracy and its critics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Denny, K., & Doyle, O. (2008). Political interest, cognitive ability and personality: Determinants of voter turnout in Britain. British Journal of Political Science, 38(02), 291–310.

Dowding, K., John, P., & Rubenson, D. (2012). Geographic mobility, social connections and voter turnout. Journal of Elections Public Opinion and Parties, 22(2), 109–122.

Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. New York: Harper and Row.

Dyck, J. J., & Gimpel, J. G. (2005). Distance, turnout, and the convenience of voting. Social Science Quarterly, 86(3), 531–548.

Elklit, J., Møller, B., Svensson, P., & Togeby, L. (2005). Gensyn med sofavælgerne. Valgdeltagelse i Danmark, Århus: Århus Universitetsforlag.

Fenster, M. J. (1994). The impact of allowing day of registration voting on turnout in US elections from 1960 to 1992 a research note. American Politics Research, 22(1), 74–87.

Fieldhouse, E., & Cutts, D. (2012). The companion effect: household and local context and the turnout of young people. The Journal of Politics, 74(3), 856–869.

Franklin, M. N. (2004). Voter turnout and the dynamics of electoral competition in established democracies since 1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gerber, A. S., Green, D. P., & Larimer, C. W. (2008). Social pressure and voter turnout: Evidence from a large-scale field experiment. American Political Science Review, 102(1), 33–48.

Griffin, J. D., & Newman, B. (2005). Are voters better represented? Journal of Politics, 67(4), 1206–1227.

Gronke, P., Galanes-Rosenbaum, E., Miller, P. A., & Toffey, D. (2008). Convenience voting. Annual Review of Political Science, 11, 437–455.

Hayes, D., & Mckee, S. C. (2009). The participatory effects of redistricting. American Journal of Political Science, 53(4), 1006–1023.

Highton, B. (1997). Easy registration and voter turnout. The Journal of Politics, 59(02), 565–575.

Highton, B. (2000). Residential mobility, community mobility, and electoral participation. Political Behavior, 22(2), 109–120.

Highton, B. (2009). Revisiting the relationship between educational attainment and political sophistication. The Journal of Politics, 71(04), 1564–1576.

Highton, B., & Wolfinger, R. E. (2001). The first seven years of the political life cycle. American Journal of Political Science, 45(1), 202–209.

Hobbs, W. R., Christakis, N. A., & Fowler, J. H. (2014). Widowhood effects in voter participation. American Journal of Political Science, 58(1), 1–16.

International Idea 2015. Voter Turnout Database. I: Idea, I. (ed.). Stockholm: The International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA).

Keele, L., & Kelly, N. J. (2006). Dynamic models for dynamic theories: The ins and outs of lagged dependent variables. Political Analysis, 14(2), 186–205.

Klofstad, C. A. (2007). Talk leads to recruitment: How discussions about politics and current events increase civic participation. Political Research Quarterly, 60(2), 180–191.

Knack, S., & White, J. (2000). Election-day registration and turnout inequality. Political Behavior, 22(1), 29–44.

Lane, R. E. (1959). Political life: How and why do people get involved in politics. New York: The Free Press.

Leighley, J. E., & Nagler, J. (2013). Who votes now?: Demographics, issues, inequality, and turnout in the United States. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lijphart, A. (1997). Unequal participation: Democracy’s unresolved dilemma. American Political Science Review, 19, 1–14.

Lindsay, A. D. (1947). The modern democratic state. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Martin, P. S. (2003). Voting’s rewards: Voter turnout, attentive publics, and congressional allocation of federal money. American Journal of Political Science, 47(1), 110–127.

Mcnulty, J. E., Dowling, C. M., & Ariotti, M. H. (2009). Driving saints to sin: How increasing the difficulty of voting dissuades even the most motivated voters. Political Analysis, 17(4), 435–455.

Nickerson, D. W. (2015). Do voter registration drives increase participation? For whom and when? The Journal of Politics, 77(1), 88–101.

Panagopoulos, C. (2013). Extrinsic rewards, intrinsic motivation and voting. The Journal of Politics, 75(01), 266–280.

Persson, M. (2014). Social network position mediates the effect of education on active political party membership. Party Politics, 20(5), 724–739.

Plutzer, E. (2002). Becoming a habitual voter: Inertia, resources, and growth in young adulthood. American Political Science Review, 96(01), 41–56.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone. New York: Touchstone.

Rhine, S. L. (1995). Registration reform and turnout change in the American states. American Politics Research, 23(4), 409–426.

Riker, W. H., & Ordeshook, P. C. (1968). A theory of the calculus of voting. American Political Science Review, 62(01), 25–42.

Rosenstone, S., & Hansen, J. M. (1993). Mobilization, participation and democracy in America. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company.

Rosenstone, S. J., & Wolfinger, R. E. (1978). The effect of registration laws on voter turnout. American Political Science Review, 72(01), 22–45.

Sinclair, B. (2012). The social citizen: Peer networks and political behavior. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Smets, K., & Van Ham, C. (2013). The embarrassment of riches? A meta-analysis of individual-level research on voter turnout. Electoral Studies, 32(2), 344–359.

Squire, P., Wolfinger, R. E., & Glass, D. P. (1987). Residential mobility and voter turnout. American Political Science Review, 81(01), 45–65.

Wolfinger, R. E., & Rosenstone, S. J. (1980). Who votes?. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Zaller, J. R. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgments

I thank the editor, the anonymous reviewers and workshop participants at the Centre for Voting and Parties at the University of Copenhagen in October 2014 and at the Midwest Political Science Association’s Annual Meeting 2015 for their useful comments. I have furthermore received valuable comments from Barry Burden, Benjamin Highton, Hanna Wass, Jørgen Elklit, Kasper Møller Hansen and Yosef Bhatti. The project has received funding from the Danish Council for Independent Research (Grant No. 12-124983).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hansen, J.H. Residential Mobility and Turnout: The Relevance of Social Costs, Timing and Education. Polit Behav 38, 769–791 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9333-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9333-0