Abstract

Political scientists have documented the many ways in which trust influences attitudes and behaviors that are important for the legitimacy and stability of democratic political systems. They have also explored the social, economic, and political factors that tend to increase levels of trust in others, in political figures, and in government. Neuroeconomic studies have shown that the neuroactive hormone oxytocin, a peptide that plays a key role in social attachment and affiliation in non-human mammals, is associated with trust and reciprocity in humans (e.g., Kosfeld et al., Nature 435:673–676, 2005; Zak et al., Horm Beh 48:522–527, 2005). While oxytocin has been linked to indicators of interpersonal trust, we do not know if it extends to trust in government actors and institutions. In order to explore these relationships, we conducted an experiment in which subjects were randomly assigned to receive a placebo or 40 IU of oxytocin administered intranasally. We show that manipulating oxytocin increases individuals’ interpersonal trust. It also has effects on trust in political figures and in government, though only for certain partisan groups and for those low in levels of interpersonal trust.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

However, Muller and Seligson (1994) find that interpersonal trust is an effect rather than a cause of democracy.

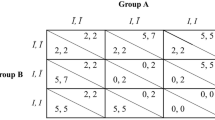

There are two players in the trust game: decision-maker 1 (DM1) and decision-maker 2 (DM2). Both are endowed with equal amounts of money. After instruction, DM1 is prompted to take an integer amount of his monetary stake, including zero, and transfer it to DM2. The selected transfer is removed from DM1 s account, and tripled in the account of DM2. DM2 is then informed of the transfer and the total in his account, and prompted to return any amount from zero to his account total back to the DM1 in his dyad. The sub-game perfect Nash equilibrium of this game is for DM2 to return nothing, and subsequently for DM1 to send nothing, though this rarely happens (Smith 1998; Zak et al. 2005).

In this game, a proposer is endowed with $10 and a responder has nothing. The proposer is asked to make an offer of a split of the money to the responder; if the responder accepts the offer, the money is paid, but if the offer is rejected, both parties get nothing.

Furthermore, this type of relationship would also be supported by existing literature in political science. Democrats are more trusting and supportive of expanding government, while Republicans champion limited government (e.g., Cook and Gronke 2005; Corey and Garand 2002; Rudolph and Evans 2005). Given Democrats' greater propensity to trust an active government, they may be more affected by OT for these types of questions.

Partisanship is also more relevant as a moderating factor given the dependent variables we are considering.

Only males are in the subject pool because one possible risk factor of taking OT intranasally is a spontaneous abortion. In females, the effects of OT also vary over the menstrual cycle.

Participants’ identities were masked throughout by assigning them an alpha-numeric code. All data were collected by computer and there was no deception of any kind.

Asians out-number whites (34 %) among undergraduates at the institution. The presence of Latinos is similar to the national population (15 %), while African Americans are under-represented (3 %). This racial and ethnic make-up is certainly not the norm in the U.S. and therefore may limit the extent to which the results travel to the U.S. population.

The p-values associated with the relevant test between the placebo and OT condition for each measure are as follows: age (p = 0.54); height (p = 0.40); weight (p = 0.46); income (p = 0.94); ideology (p = 0.29); Democrat (p = 0.45); Republican (p = 0.73); pre-treatment trust (p = 0.97); and, race and ethnicity (p = 0.61).

This is similar to the question typically used on the National Election Study. Instead of choosing between the response options of “most people can be trusted” or “you can’t be too careful in dealing with people,” subjects indicated their level of agreement with the statement that most people can be trusted. Please see supplementary Table A in the supplemental document for summary statistics on all of our variables.

We use a one-tailed test since we expect a positive effect of OT on interpersonal trust. However, the effect is also significant using a two-tailed test, though only at p < 0.10. We also find similar effects if we just run a difference in means test on interpersonal trust between the OT and placebo, though the effects are outside of standard significance levels (p = 0.11, one-tailed). Even though it was not part of our expectations for interpersonal trust, we explored whether partisanship moderated the effects of OT and did not find this to be the case.

We are left with 19 Democrats on placebo and 17/18 on OT, 10 Republicans on placebo and on OT, and 12 Independents on placebo and 18/19 Independents on OT.

As we noted earlier, it would also have been good to have pre-treatment measures for all of our dependent variables but we were unable to do this due to limited space on the survey.

In the few instances where we find a sign opposite of expectations, we use a two-tailed test.

In a model without the interaction term, OT increases trust in Clinton among Democrats.

In the model without interaction terms, OT leads to a drop in trust toward Edwards among Republicans and an increase in trust among Independents.

Only one factor emerged with an eigenvalue over 1 and both measures had similar weights.

Previous work on OT infusion has tested for racial or ethnic differences in response to OT and no effects have been found (Morhenn et al. 2008; Zak et al. 2005a, b; Zak et al. 2007). As another check for external validity, we ran all of our analyses using race and ethnicity dummy variables and in only two cases do we find that the Asian dummy variable is statistically significant and its inclusion washes away the effect of OT. This is in the analysis of trust in George Bush and trust in Mitt Romney among Democrats.

This stimuli brings to mind the iconic image of authoritarian regimes. Such displays may therefore not only convey the power of the regime, but foster bonds of trust with the public in these societies.

It is important to note that the temporal effects of any OT-induced changes in trust remain unclear. An individual’s feelings of trust may return to previous levels as OT is metabolized. Alternatively, feelings held during hormonally spiked experiences may be encoded and permanently alter beliefs.

This is based on studies from our lab. Since it is a non-result, it is unpublished.

See for example the Pew Center for People and the Press, “The Gender Gap: Three Decades Old, as Wide as Ever.” Accessed on December 17, 2012, at http://www.people-press.org/2012/03/29/the-gender-gap-three-decades-old-as-wide-as-ever/.

References

Abramowitz, A. I., Saunders, K. L., & K.L., (1998). Ideological realignment in the U.S. electorate. Journal of Politics, 60, 634–652.

Almond, G. A., & Verba, S. (1963). The civic culture: Political attitudes and democracy in five nations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Amodio, D. M., Jost, J. T., Master, S. L., & Yee, C. M. (2007). Neurocognitive correlates of liberalism and conservatism. Nature Neuroscience, 10, 1246–1247.

Andari, E., Duhamel, J., Zalla, T., Herbrecht, E., Leboyer, M., & Sirigu, A. (2010). Promoting social behavior with oxytocin in high functioning autism spectrum disorders. PNAS, 107(9), 4389–4394.

Anderson, C. J., & Tverdova, Y. V. (2003). Corruption, political allegiances, and attitudes toward government in contemporary democracies. American Journal of Political Science, 47, 91–109.

Avery, J. M. (2009). Political mistrust among African Americans and support for the political system. Political Research Quarterly, 62(1), 132–145.

Barraza, J. A., Ropacki, S., & Zak, P. J. Age, oxytocin release, and generosity (in progress).

Barraza, J. A., & Zak, P. J. (2009). Empathy toward strangers triggers oxytocin release and subsequent generosity. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1167, 182–189.

Bartels, L. M. (2000). Partisanship and voting behavior. American Journal of Political Science, 44, 35–50.

Bayliss, A. P., & Tipper, S. P. (2006). Predictive gaze cue and personality judgments: Should eye trust you? Psychological Science, 17, 514–520.

Booth, J. A., & Richard, P. B. (1998). Civil society, political capital, and democratization in Central America. The Journal of Politics, 60, 780–800.

Born, J., Lange, T., Kern, W., McGregor, G. P., Bickel, U., & Fehm, H. L. (2002). Sniffing neuropeptides: a transnasal approach to the human brain. Nature Neuroscience, 5, 514–516.

Brehm, J., & Rahn, W. (1997). Individual-level evidence for the causes and consequences of social capital. American Journal of Political Science, 41, 999–1023.

Bremner, J. D., Krystal, J. H., Southwick, S. M., & Charney, D. S. (1995). Functional neuroanatomical correlates of the effects of stress on memory. Journal of Trauma and Stress, 8, 527–554.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American voter. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Chanley, V., Rudolph, T. J., & Rahn, W. M. (2000). The origins and consequences of public trust in government: A time series analysis”. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 64, 239–256.

Citrin, J. (1974). Comment: The political relevance of trust in government. The American Political Science Review, 68, 973–988.

Citrin, J., & Green, D. P. (1986). Presidential leadership and the resurgence of trust in government. British Journal of Political Science, 16, 431–453.

Citrin, J., McClosky, H., Shanks, J. M., & Sniderman, P. M. (1975). Personal and political sources of political alienation. British Journal of Political Science, 5, 1–31.

Cook, T. E., & Gronke, P. (2005). The skeptical American: Revisiting the meanings of trust in government and confidence in institutions. The Journal of Politics, 67, 784–803.

Corey, E. C., & Garand, J. C. (2002). Are government employees more likely to vote? An analysis of turnout in the 1996 U.S. national election. Public Choice, 111, 259–283.

Craig, S. C. (1993). The malevolent leaders: popular discontent in America. Boulder, CO: WestView.

Craig, S. C. (1996). Broken contract: changing relationships between Americans and their government. Boulder, CO: WestView.

Dennis, J., & Owen, D. (2001). Popular satisfaction with the party system and representative democracy in the United States. International Political Science Review, 22, 399–415.

Dodd, M. D., Hibbing, J. R., & Smith, K. B. (2011). The politics of attention: gaze-cuing effects are moderated by political temperament. Attention, Perception & Psychophysics, 73, 24–29.

Domes, G., Heinrichs, M., Michel, A., Berger, C., & Herpertz, S. C. (2007). Oxytocin improves “mind-reading” in humans. Biological Psychiatry, 61, 731–733.

Geddes, L. (2010). With this test tube I thee wed. New Scientist, Feb., 13, 32–35.

Guastella, A. J., Mitchell, P. B., & Dadds, M. R. (2008). Oxytocin increases gaze to the eye region of human faces. Biological Psychiatry, 63, 3–5.

Halpern, D. (2001). Moral values, social trust and inequality can values explain crime? The British Journal of Criminology, 41(2), 235–251.

Heinrichs, M., Baumgartner, T., Kirschbaum, C., & Ehlert, U. (2003). Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress. Biological Psychiatry, 54, 1389–1398.

Hetherington, M. J. (1998). The political relevance of political trust. The American Political Science Review, 92, 791–808.

Hetherington, M. J. (1999). The effect of political trust on the presidential vote, 1968–96. The American Political Science Review, 93, 311–326.

Hetherington, M. J. (2004). Why trust matters: declining political trust and the demise of American liberalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hetherington, M. J., & Globetti, S. (2002). Political trust and racial policy preferences. American Journal of Political Science, 46, 253–275.

King, A. (1997). The vulnerable American politician. British Journal of Political Science, 27, 1–22.

Knack, S., & Zak, P. J. (2003). Building trust: Public policy, interpersonal trust, and economic development. Supreme Court Economic Review, 10, 91–107.

Kosfeld, M., Heinrichs, M., Zak, P. J., Fischbacher, U., & Fehr, E. (2005). Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature, 435, 673–676.

Levi, M., & Sherman, R. (1997). Rationalized bureaucracies and rational compliance. In C. Clague (Ed.), Institutions and economic development. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lin, P., Grewal, N. S., Morin, C., Johnson, W. D., & Zak, P. J. (in press). Oxytocin increases the influence of public service advertisements. Public Library of Science ONE.

Lipset, S. M., & Schneider, W. (1983). The decline of confidence in American institutions. Political Science Quarterly, 98, 379–402.

Locke, S. T., Shapiro, R. Y., & Jacobs, L. R. (1999). The impact of political debate on government trust: Reminding the public what the federal government does. Political Behavior, 21, 239–264.

Marcus, G. E., Neuman, W. R., & MacKuen, M. (2000). Affective intelligence and political judgment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McCabe, K., Houser, D., Ryan, L., Smith, V., & Trouard, T. (2001). Proclamation to National Academy of Sciences, 98, 11832–11835.

Miller, A. H. (1974). Political issues and trust in government 1964–1970. American Political Science Review, 68, 951–972.

Moore, C., & Dunham, P. J. (Eds.). (1995). Joint attention: Its origins and role in development. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Morhenn, V. B., Park, J. W., Piper, E., & Zak, P. J. (2008). Monetary sacrifice among strangers is mediated by endogenous oxytocin release after physical contact. Evolution and Human Behavior, 29, 375–383.

Muller, E., & Seligson, M. A. (1994). Civic culture and democracy: The question of causal relationships. The American Political Science Review, 88, 635–652.

Orren, G. (1997). Fall from grace: The public’s loss of faith in government. In P. Zelikow, J. Nye Jr, & D. C. King (Eds.), Why people don’t trust government. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Oxley, D. R., Smith, K. B., Alford, J. R., Hibbing, M. V., & Miller, J. R. (2008). Political attitudes vary with physiological traits. Science, 321(5896), 1667–1670.

Putnam, R. P. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Putnam, R. P. (1995). Tuning in, tuning out: The strange disappearance of social capital in America. PS: Political Science and. Politics, 28, 664–683.

Putnam, R. P. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Ragsdale, L. (1991). Strong feelings: Emotional responses to Presidents”. Political Behavior, 13, 33–65.

Rahn, W. M., & Transue, J. E. (1998). Social trust and value change: The decline of social capital in American youth, 1976–1995. Political Psychology, 19, 545–565.

Rotter, J. B. (1980). Interpersonal trust, trustworthiness, and gullibility. American Psychologist, 35, 1–7.

Rudolph, T. J., & Evans, J. (2005). Political trust, ideology, and public support for government spending. American Journal of Political Science, 49, 660–671.

Schildkraut, D. J. (2005). The rise and fall of political engagement among Latinos: The role of identity and perceptions of discrimination. Political Behavior, 27(3), 285–312.

Scholz, J. T., & Lubell, M. (1998). Trust and taxpaying: Testing the heuristic approach to collective action. American Journal of Political Science, 42, 398–417.

Smith, V. (1998). The two faces of Adam Smith. Southern Economic Journal, 65(1), 2–19.

Sturgis, P., Read, S., Hatemi, P. K., Zhu, G., Trull, T., Wright, M. J., et al. (2010). A genetic basis for social trust? Political Behavior, 32, 205–230.

Tavits, M. (2006). Making democracy work more? Exploring the linkage between social capital and government performance. Political Research Quarterly, 59, 211–225.

Tomz, M., Wittenberg, J., & King, G. (2001). CLARIFY: Software for interpreting and presenting statistical results. Version 2.0. Cambridge: Harvard University.

Tyler, T. R. (1994). Governing amid diversity: The effect of fair decisionmaking procedures on the legitimacy of government. Law & Society Review, 28, 809–831.

Uslaner, E. M. (1998). Social capital, television, and the “Mean World”: Trust, optimism, and civic participation. Political Psychology, 19, 441–467.

Uslaner, E. M. (2002). The moral foundations of trust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Weingast, B. R. (1997). The political foundations of democracy and the rule of law. The American Political Science Review, 91, 245–263.

Zak, P. J. (2008). The neurobiology of trust. Scientific American, June, 88–95.

Zak, P. J. (2011). The physiology of moral sentiments. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 77, 53–65.

Zak, P. J. (2012). The moral molecule: Vampire economics and the new science of good and evil. New York, NY: Dutton Press.

Zak, P. J., Borja, K., Matzner, W. T., & Kurzban, R. (2004). The neurobiology of trust. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1032, 224–227.

Zak, P. J., Borja, K., Matzner, W. T., & Kurzban, R. (2005a). The neuroeconomics of distrust: Sex differences in behavior and physiology. Cognitive Neuroscience Foundations of Behavior, 95, 360–363.

Zak P.J., Borja, K., Matzner, W.T., & Kurzban, R. (2005b). Oxytocin is associated with human trustworthiness. Hormones and Behavior, 48, 522–527.

Zak, P. J., & Knack, S. (2001). Trust and growth. The Economic Journal, 111, 295–321.

Zak, P. J., Stanton, A. A., & Ahmadi, S. (2007). Oxytocin increases generosity in humans. Public Library of Science One, 2, e1128.

Zaller, J. R. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant to Paul J. Zak from the John Templeton Foundation. We thank the anonymous reviewers and editors for helpful feedback.

The experiments comply with the current laws of the United States. All of the procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the universities involved.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Merolla, J.L., Burnett, G., Pyle, K.V. et al. Oxytocin and the Biological Basis for Interpersonal and Political Trust. Polit Behav 35, 753–776 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-012-9219-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-012-9219-8