Abstract

Aims

Silicon (Si) has been shown to beneficially affect plant performance under stressful environmental conditions, such as water or nutrient deficiency. Here we tested the effects of two important plant nutrients, nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P), on Si content in different plant organs in the grass species Holcus lanatus.

Methods

We studied trait responses to N limitation, balanced nutrient availability and P limitation. Single plant individuals were grown in sand-filled pots in a greenhouse for 2 months. Nitrogen, phosphorus, carbon and silicon contents were determined in leaves, stems and roots, as were leaf and roots traits, biomass production and root enzyme activity.

Results

Si content was lowest under balanced nutrient supply in all plant organs. Under P limitation Si content was highest in leaves and stems, in roots it was highest under N limitation. Si:C ratios were lowest under balanced conditions, and highest under nutrient limitation. Root phosphatase activity was highest under P limitation and chlorophyll content was lowest under N limitation.

Conclusions

Our model species assimilated less ‘high cost C’ and took up more ‘low cost Si’ under nutrient limitation, especially under P deficiency. Si potentially plays an important role in different environments, such as nutrient or light limitation, which in turn may be related to different plant strategies, for example higher stem rigidity in high Si plants versus higher stem flexibility in low Si plants. More research is needed to further elucidate the role of silicon in different concepts of trait-environment relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Essential nutrients for plant growth are defined as elements necessary for plants to complete their lifecycle, which are directly involved in a plants’ metabolism and which cannot be replaced by other elements (Marschner 2012). Seventeen different elements are considered essential for plants, among them carbon (C), and the plant nutrients nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P). Nitrogen constitutes about 1–5% of a plant’s dry mass and is the second most abundant nutrient in plant tissue. It forms an integral element in nucleic acids, co-enzymes, proteins, phytohormones, secondary metabolites and chlorophyll (Marschner 2012). Poor uptake of N by roots or low availability in the soil therefore negatively affect plant productivity and competitiveness (Minden and Olde Venterink 2019; Olde Venterink and Güsewell 2010). Phosphorus, though less abundant, is essential for energy transport and is an integral component of DNA and RNA. Under P deficiency photosynthesis is hampered (Güsewell 2005a), shoot growth is reduced and leaves show a premature senescence (Marschner 2012). In plants, N and P are both functionally linked, the strongest link is their significant role in photosynthetic enzymes and the production of these enzymes (Marschner 2012; Sterner and Elser 2002).

Carbon makes up almost half of the dry substance of plants and contributes to their structure, metabolism, light adsorption and energy storage (Sterner and Elser 2002). The high binding energy of C probably favoured its selection over other elements, such as silicon, which is in the same column of the periodic table (implying some similar properties) (Mason 1966; Williams and Fraústo da Silva 1996).

Silicon (Si) is considered a beneficial element, as it can stimulate growth but it is not essential for it (Pilon-Smits et al. 2009). However, all soil-grown plants contain silicon (Epstein 1994). Its uptake depends on soluble Si in the soil, which originates from lithogenic and pedogenic silicates and, in the course of the weathering process, originates from amorphous phytogenic silicates released from organic material through decomposition processes (Cornelis and Delvaux 2016). Although Si can be very abundant in the soil (up to 470 g kg-1 soil, Cornelis and Delvaux 2016; McKeague and Cline 1963), crystalline Si minerals (e.g. quartz or olivine) weather very slowly and are more or less unavailable for plants (Fraysse et al. 2006). Si is taken up both actively and passively from the soil in the form of silicic acid, and precipitated as amorphous silica (Cooke and Leishman 2011a; Coskun et al. 2019; Exley 2015; Ma and Takahashi 2002; Ma and Yamaji 2015), which is also its predominant form in roots and shoots. Like carbon, Si can form bonds with four other atoms at once and form long chains (polymers). Unlike C, chains formed with Si are not as stable as hydrocarbon chains and although Si can bind to oxygen, it remains in its solid form and is not transformed into gaseous carbon dioxide, which can diffuse out of the cells (Sterner and Elser 2002). Amorphous silica compounds, called phytoliths (Cooke and Leishman 2011a) can be deposited anywhere in the plant, within or between cells or as part of the cell wall, but cannot be relocated after deposition (Piperno 2006; Raven 1983).

The effects of silicon on plant performance are numerous: it can alleviate physical stress, such as drought, high and low temperatures and UV radiation (Hattori et al. 2005; Schaller et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2005) and chemical stress like salt stress and metal toxicity (Coskun et al. 2016; Epstein 2009; Katz 2019; Ma et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2004). Further, it enhances the resistance of plants to diseases caused by fungi and bacteria and suppresses pests such as phytophagous insects, leaf spiders and mites (Cai et al. 2008; Van Bockhaven et al. 2013).

It has been suggested that silicon can substitute for carbon and cellulose (Schaller et al. 2012a, b; Schoelynck et al. 2010) in some functions, such as structural support (McNaughton et al. 1985). Further, uptake of silicon is energetically less expensive than uptake of carbon, whereas at the same time it is more disposable than carbon (O'Reagain and Mentis 1989). The calculated energy costs of silicon versus carbon are 1:10 to 1:20 by weight (Raven 1983). For example, silicon was shown to be negatively related to the energetically more expensive lignin in Oryza sativa (Klotzbücher et al. 2018). It has been suggested that the silicon-accumulating species of the Poales family evolved under low CO2 levels, and a higher Si uptake rate of silicon gave those species a competitive advantage over species which lacked this competence (Craine 2009).

Cooke and Leishman (2011a) suggested that in environments in which carbon acquisition is limited (i.e. under low CO2-availability, low light conditions or in aquatic environments), the use of silica is favoured over carbon. Another possible environment in which a higher uptake rate of Si might be advantageous for plant performance is nutrient limited conditions. Studies have shown that Si alleviated stresses caused by nutrient deficiency, such as potassium (K, Chen et al. 2016), iron (Fe, Pavlovic et al. 2016) or phosphorus (P, Kostic et al. 2017) deficiency. Here we ask how plants respond to both nitrogen and phosphorus limitation in respect to silicon uptake compared to balanced nutrient supply (i.e. no limitation by either N or P). Plants respond differently to either N or P limitation: under N limitation chlorophyll content is reduced, plants reduce leaf area, root deeper, accelerate total root length and increase transpiration to accelerate delivery of ions to the root surface by mass flow (Dunbabin et al. 2003; Garnett et al. 2009; Marschner 2012; Olde Venterink and Güsewell 2010). Phosphorus limitation generally hampers photosynthesis, stimulates biomass turnover, plants exhibit greater root branching, greater root length/mass quotient (i.e. specific root length, SRL) and higher investment into phosphatases to degrade organic P-compounds (Holdaway et al. 2011; Olde Venterink and Güsewell 2010; White et al. 2013). Whereas it has been shown that plant performance is lower under low Si availability compared to elevated Si availability (Neu et al. 2017), it is unclear how plants respond in respect to Si uptake under limitation of other nutrients, such as N or P.

Silicon plays an important role in plant functioning under stressful conditions, yet under benign conditions its role is often minimal or non-existent (see studies presented in Table 1 of Coskun et al. 2019; Epstein 2009; Ma and Takahashi 2002). Here, we ask if this also applies to the uptake rate of Si in plants under different nutrient conditions. We expect that plants take up more silicon under nutrient limited conditions than under balanced nutrient conditions, as other studies showed that beneficial effects of Si were highest under stressful abiotic conditions (e.g. under salt stress, Flam-Shepherd et al. 2018). We further question if plant-silicon-responses differ between N and P limitation, as it was shown for other plant traits (e.g. reduced chlorophyll content under N limitation or increased phosphatase activity under P limitation, Marschner 2012; Minden and Olde Venterink 2019; Olde Venterink and Güsewell 2010). For this we conducted a greenhouse experiment with Holcus lanatus L., which belongs to the Poaceae, a family known for its high Si-accumulation (Hodson et al. 2005). Plants were exposed to N limited conditions, balanced nutrient concentrations and P limited conditions. Variation of nutrients followed a well-tested design (see e.g. Olde Venterink and Güsewell 2010), originally introduced by Güsewell (2005a). We measured concentrations of N, P, C and Si in every plant organ, as well as plant traits known to respond to variation in nutrient availability, such as biomass production, root mass ratio, chlorophyll content, phosphatase activity and specific root length (Craine et al. 2005; Minden and Olde Venterink 2019; Olde Venterink and Güsewell 2010).

Materials and methods

Study species

Holcus lanatus L., commonly known as Yorkshire fog, belongs to the family of Poaceae. Its original range is Europe, though it is widely distributed throughout temperate regions of the world and can be a weedy invader of pastures and grasslands (Thompson and Turkington 1988). It is perennial and produces 20–100 cm high culms, 4–20 cm long greyish-green leaves and is of low palatability to livestock (Jaques 1974). Silicon concentration has been reported as 2.7% for this species (dry mass, Massey et al. 2007).

Experimental design

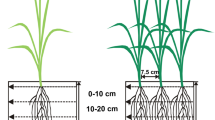

Seeds of H. lanatus were ordered from Cruydt Hoeck, Nijeberkoop, The Netherlands, germinated, and seedlings were transplanted approximately 3 weeks after germination in May 2017. About 20 seedlings were immediately harvested to determine initial biomass for the calculation of relative growth rate (RGR). Initial biomass was on average 3.38 mg. Each planting pot (10 cm high, 8 cm wide) was filled with 400 ml fine quartz sand and contained one plant individual. The sand was ordered from Sibelco Benelux (Antwerp, Belgium), type M31, containing 99.5% SiO2 (0.04% FeO3, 0.2 Al2O3, 0.03 TiO2, 0.03 K2O, 0.01 CaO) and pH of 7. The sand was analysed for N and P contents, and the two nutrients were below detection limits (for methods, see Cebrián-Piqueras et al. 2017). The experiment was conducted with three N:P supply ratios (1.7, 15 and 135 mass based), which corresponded to N limited conditions (N:P = 1.7), balanced conditions (N:P = 15) and P limited conditions (N:P = 135). The design followed the approaches of Güsewell (2005a, b). Absolute supplies of N and P varied threefold between each treatment. For example, the lowest N supply was applied to the N limited treatment (total supply of 20 mg N per pot) and the highest to the P limited treatment (total supply of 180 mg N per pot), whereas the lowest supply of P was applied to the P limited treatment (total supply of 1.33 mg P per pot) and the highest to the N limited treatment (total supply of 12 mg P per pot). The balanced nutrient treatment took an intermediate position, with a total supply of 60 mg N and 4 mg P per pot. This resulted in N:P ratios of 1.7 (N limited treatment), 15 (balanced supply) and 135 (P limited treatment).

Each pot was planted with one plant individual, and each treatment was represented by 15 replicates, resulting in a total of 45 pots. Throughout the entire course of the experiment, a total of 40 ml nutrient solution was given to each individual, 2.5 ml of nutrient solution in the first 2 weeks, 5 ml in weeks 3 to 6 and 7.5 ml in the last 2 weeks. Nutrient solutions were pipetted on the sand around the stems once per week. N was applied as NaNO3 and P as NaH2PO4. The same amounts of macro- and micronutrients were applied weekly in nutrient solutions to all plant individuals (total per pot: 444 mg K (as KCl), 110 mg Ca (as CaCl2.2H2O), 41 mg S (as MgSO4.7H2O), 31 mg Mg (MgSO4.7H2O), 10 mg Fe (FeSO4.7H2O), 0.8 mg B (H3BO3), 0.06 mg Cu (CuSO4.5H2O), 0.5 mg Mn (as MnCl2.4H2O), 0.2 mg Zn (ZnSO4.7H2O), 0.1 mg Mo (as Na2MoO4.2H2O), again calculated after Güsewell (2005a)). Additionally to the nutrients applied once per week, plants were watered with de-ionized water upon demand (i.e. when the upper layer of sand was dry and the saucer did not contain any more water, approximately 1–2 times per week) into the saucers to avoid leaching of the nutrients from the sand, and to avoid edge and/or shading effects, pots were regularly rearranged.

Harvest and measurements of plant traits

The main harvest took place 8 weeks after the first nutrient application, from 08 to 13 July 2017. Sand was washed off the roots and individuals were separated into leaves, stems and roots. Leaves consisted of the leaf blades, whereas we assigned the petioles to the stems, because other than in herbs, leaf petioles in grasses contribute significantly to its upright stability and as such function as part of the stem. Biomass samples were oven dried at 70 °C for 72 h and weighed.

To determine element concentrations, plant material of each organ of each individual was ground in a mixer mill (Retsch MM 400, Haan, Germany). Analysis of Si concentration in plant material was done by extraction in a 0.1 M Na2CO3 solution at 85 °C for 5 h according to DeMaster (1981). Silicon was measured by ICP-OES, after sample filtration (0.2 μm cellulose acetate). For C and N analyses, 2–3 mg of material was placed into tin tubes (0.1 mg precision balance CP 225 D; Sartorius, Goettingen, Germany) and analysed using a CHNS Analyser Flash EA (Thermo Electron Corp., Waltham, MA, USA) following Allen (1989). Total P concentrations were measured with a continuous segmented flow analyser (QuAAtro, SEAL Analytical, Norderstedt, Germany), after combustion and hot HCl extraction of 5 mg of material per sample (Andersen 1976; according to Johengen 1997). Element concentrations of N, P, C and Si refer to mg g−1.

Relative growth rate (RGR) was calculated as RGR = (logW2 – logW1) / (t2 – t1), with W2 and W1 representing the biomass at the sequential times t2 (time of harvest) and t1 (start of experiment), respectively (in days, Hunt 1990). Root phosphomonoesterase activity (PME activity) was measured by processing fresh root tissue (100 mg) with para-nitrophenyl phosphate and tris(hydroxymethyl-)aminomethane/maleate (Hogan et al. 2010; Olde Venterink and Güsewell 2010). Absorbance was measured using a photospectrometer at 410 nm (Genesys™ 10 Series Spectrophotometer, Thermo Spectronic, Darmstadt, Germany). PME activity refers to μmol pNPP cleaved per g fresh root per hour, for further method description see Olde Venterink (2011).

To determine specific root length (m mg−1), a representative subsample of fine roots of each root sample was cut off, stored in 70% ethanol and scanned (LA2400 scanner for WinRhizo®, Regent Instruments Inc. 2013, Quebec, Canada) with simultaneous use of WinRhizo® software (Regent Instruments Inc. 2013). Subsequently, samples were dried (70 °C, 72 h), and weights were added to the remaining root weights. Results from WinRhizo® were converted to refer to total root mass where applicable.

Specific leaf area (SLA, mm2 mg−1) was determined by clipping off two leaves per individual and by measuring their dry weight and area (flatbed scanner and computer software ImageJ, Rasband 2014). SLA is the mean area of the two leaves divided by their mean dry weight (Pérez-Harguindeguy et al. 2013). Chlorophyll content was determined with a Chlorophyll Meter 502-SPAD Plus (Konica Minolta, Munich, Germany). From each of the two leaves clipped off for SLA determination, five SPAD measurements were taken, SPAD values were calibrated to chlorophyll contents (for methods see Minden et al. 2017) and refer to leaf dry weight (Total Chl, μg mg−1). SPAD units were converted into chlorophyll content via ordinary least square regression (R2 0.71, p > 0.001). Root Mass Ratio (RMR, mg mg−1) is the ratio of biomass allocation to roots and shoots.

Statistical analyses

Trait-differences between treatments (i.e. N limitation, balanced nutrient conditions, P limitation) were tested with analysis of variance, with aov(x ~ Treatment) (Chambers et al. 1992). Prior to analyses, residuals were tested for normal distribution and variances for homogeneity. Data were transformed (log, square root or boxcox) if necessary. Post hoc tests were performed with Tukey Honest Significant Differences-Test (Yandell 1997).

Standardised major axis (SMA) slope-fitting techniques were used to analyse bivariate relationships between plant minerals across all treatments (Warton et al. 2006). We first tested for normal distribution of the data and transformed where appropriate. We then tested for significant correlations between pairs of plant elements at p < 0.05 (Pearson’s r, e.g. between Si leaf vs C leaf), and, for pairs which were significantly correlated, calculated the intercepts of the regression line with the y-axis (elevation) and the slope of the regression line. Lastly, we tested if the regression line is significantly different from one, which indicates an unequal increase of both variables. To test for significant differences of Si content in plant organs between different treatments within a range of C contents in each plant organ, we conducted linear models with an interaction of treatment and C content (i.e. lm(Si ~ trt*C)). As all interactions between treatment and C content yielded insignificant results, we conducted multiple comparisons to test for group differences (i.e. differences in treatments). Analyses were performed using the computer software RStudio (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2019) and the R packages ‘car’ (Fox and Weisberg 2019), ‘geoR’ (Box and Cox 1964) and ‘sma’ (Warton et al. 2012) and ‘multcomp’ (Hothorn et al. 2008).

Results

Across plant organs and treatments, silicon content varied from a minimum average of 15.8 mg g−1 (under balanced nutrient conditions) to a maximum of 45.4 mg g−1 (under P limitation) (Fig. 1a–c). Variation was highest in roots. For all three plant organs, Si content was significantly lowest under balanced nutrient supply. In leaves and stems, it was highest under P limitation and second highest under N limitation, whereas in roots it was highest under N limitation and second highest under P limitation (at p < 0.05). Si stock (Si content multiplied by biomass) was significantly different between treatments, with lowest values in the P limited treatments (across all plant organs) and highest in roots and stems (P limited and balanced nutrient supply, respectively, Supplementary Fig. 1, A-C).

Silicon and carbon contents (mg g−1) and Si:C ratios (mg mg−1) in Holcus lanatus plant tissue grown under N:P ratios of 1.7 (N limitation), 15 (balanced supply) and 135 (P limitation). a–c: silicon content of leaves, stems and root, d–f: carbon content of leaves stems and roots and g–i: Si:C ratio of leaves, stems and roots. Bars show mean values with standard deviation (n = 15 for each group). Use of different letters indicates significant differences between groups at p < 0.05. For N and P content in leaves, stems and roots see Supporting Information Fig. 2, for Si:N, Si:P, N:C and P:C ratios of total biomass see Supporting Information Fig. 3

Carbon content showed the reverse patterns to silicon content: it was significantly higher under balanced nutrient conditions than under both N (p < 0.005) and P limited conditions (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1d–f). Carbon content did not differ significantly between N and P limitation for leaves and roots (p: 0.58 and 0.85), but was significantly lowest under P limitation in stems (p < 0.001). It varied from a minimum average of 325 mg g−1 in stems (under P limitation) to a maximum of 392 mg g−1 in roots (under balanced conditions), with greatest variance in leaves (under P limitation).

N and P content in leaves, stems and roots also differed significantly between the nutrient treatments: N content was lowest under N limited conditions (15.3 mg g−1 in leaves, 8.8 mg g−1 in stems and 7.8 mg g−1 in roots) and highest under P limited conditions (mean of 27.4, 17.4 and 12.9 mg g−1 in leaves, stems and roots), whereas values under balanced nutrient supply were intermediate (24.4, 12.2 and 10.9 mg g−1 in leaves, stems and roots, Supplementary Fig. 2, A-F). The reverse (highest under N limitation, lowest under P limitation) was apparent for P content in leaves, stems and roots.

As with contents of silicon and carbon, ratios of silicon versus carbon (Si:C ratios) also differed between N limitation, balanced conditions and P limitation (Fig. 1g-i): for all plant organs Si:C ratios were lowest under balanced conditions, and highest under nutrient limited conditions. For leaves and stems Si:C ratios were highest under N limitation, whereas they were highest under P limitation in roots (for biomass ratios of Si:N, Si:P, N:C and P:C see Supplementary Fig. 3 A-D).

Correlation coefficients for Si and C contents across treatments between all organs were significant (all but C content in leaf vs root, Table 1). All combinations between organs (stem vs leaf, stem vs root and leaf vs root) for silicon scaled isometric, meaning the allocation of Si in one organ was accompanied by a similar allocation in the other organ (see slopes of regression and non-significant p value for test of slope-deviation from 1 in Table 1). For C, slope was only significant (and isometric) for stem vs leaf, the other combinations were non-significant.

When Si was scaled against C across all treatments, slopes of regression were negative for all plant organs (Table 1, lower part and Fig. 2a–c). Slope values between −3.89 and − 5.10 indicated a stronger decrease in Si accompanied by a less strong increase in C. In other words, across the treatments from nutrient balanced conditions to nutrient limited conditions (both N and P), the amount of Si in the plant tissue increased stronger than C content decreased (Fig. 2a–c). Si content was significantly higher in the P limited treatments than in the N limited treatments under a similar C content for all plant organs (p < 0.01). Similarly, Si content was significantly higher under N limitation compared to balanced nutrient supply (p < 0.05), and significantly higher under P limitation compared to balanced nutrient supply in leaves and stems (p < 0.001), but not in roots (p = 0.41).

Standardized major axis (SMA) regression relationships of Si versus C in leaves (a), stems (b) and roots (c). Shown are values for N limited treatment (grey triangles), balanced nutrient supply (white circles) and P limited treatment (dark grey boxes). All relationships are significant at p < 0.05. Light grey lines indicate 95% lower confidence intervals

Relative growth rate (RGRTotal) was highest under balanced nutrient conditions, second highest under N limited conditions and lowest under P limited conditions (all significantly different at p < 0.001), as were biomass allocation to leaves, stems and roots (Figs. 3a and 4a–c). Biomass N:P ratio showed a similar pattern as root phosphatase (PME) activity and specific root length: values were highest under P limitation and lowest under N limitation (Fig. 3b-d). Chlorophyll content was significantly lower under N limitation than both under balanced nutrient conditions and P limitation (Fig. 3e), whereas root mass ratio and specific leaf area were significantly higher under N limitation compared to the remaining treatments (Figs. 3f and 4d).

Relative growth rate of total biomass (a), N:P ratio of total biomass (b), Chlorophyll content (c), root phosphatase (PME) activity (d), Root Mass Ratio (e) and Specific Root Length (f) of Holcus lanatus grown under N:P ratios of 1.7 (N limitation), 15 (balanced supply) and 135 (P limitation). Bars show mean values with standard deviation (n = 15 for each group). Use of different letters indicates significant differences between groups at p < 0.05

Biomass allocation to leaves (a), stems (b) and roots (c), and Specific Leaf Area (d) of Holcus lanatus grown under N:P ratios of 1.7 (N limitation), 15 (balanced supply) and 135 (P limitation). Bars show mean values with standard deviation (n = 15 for each group). Use of different letters indicates significant differences between groups at p < 0.05

Discussion

The grass species Holcus lanatus contained more silicon and less carbon under nutrient limitation (N and P limitation) than under balanced nutrient conditions, which was reflected in higher tissue Si:C ratios under nutrient limitation. These effects were stronger under P limitation in leaves and stems, whereas they were stronger under N limitation in roots (Fig. 1). Furthermore, scaling relationships showed that the slope of regression (SMA) was lowest in stems (−5.10, Table 1), indicating a stronger absence of carbon compared to silicon in this plant organ compared to leaves and roots.

Especially under resource limited conditions, increased uptake of silicon is seen as advantageous for plant performance, as the use of Si requires less energy during formation of cell compounds (Raven 1983). For example, the study of Schoelynck et al. (2010) showed that silicon and cellulose were positively correlated in wetland species and negatively correlated in aquatic species. They attributed these opposing patterns to differences in growth-strategies between the two groups of species: a higher rigidity in wetland species promoting upright stature (for which silicon is an energetically cheap stiffening material) and a higher flexibility in aquatic species to endure hydrodynamic forces. A study with emergent and submerged plants in a natural wetland vegetation revealed a negative relationship between Si and C, and this relationship was stronger in submerged species than in emergent species (Schaller et al. 2016). The authors concluded that the favour for Si over C may stem from lower C and light availabilities in the submerged environment. Our experimental study showed the same patterns, higher uptake of Si and a lower assimilation of C, yet under nutrient limitation and not under light limitation. However, both nutrient limitation and light limitation are known to affect the photosynthesis of plants, the first by for example diminishing chlorophyll synthesis (Marschner 2012).

Whereas the abovementioned studies attributed the observed patterns to light limitation, our study provides evidence for a Si-effect under nutrient limitation. Both N and P limitation led to increased Si uptake and decreased C assimilation compared to balanced nutrient conditions and this effect was stronger under P limitation than under N limitation. This is consistent with an observed stronger reduction of the growth of the Holcus plants under P limitation in our experiment, as well as a stronger reduction of growth and photosynthesis rates of Carex species under P limitation than under N limitation compared to balanced N:P supply, determined under the same experimental conditions as in our experiment (including N:P supply ratios of 1.7, 15 and 135; Güsewell 2005b).

Our study further showed differences in Si accumulation between plant organs. On average and across treatments, roots showed the highest Si concentrations (mean of 31.8 mg g−1 compared to 25.9 mg g−1 in leaves and 27.9 mg g−1 in stems). Under N limitation and balanced conditions roots also showed the highest Si concentration (mean of 43.3 mg g−1 and 21.2 mg g−1, Fig. 1c), whereas stems accumulated most Si under P deficiency (mean of 45.4 mg g−1, Fig. 1b) and showed lowest C content under P limitation (slope of −5.10, Table 1). The same patterns were found for Si:C ratios. Further, total Si:C ratios (i.e. not separated into different plant organs) significantly differed between treatments, with Si:C ratio being lowest under balanced nutrient conditions (0.044), second lowest under N limitation (0.087) and highest under P limitation (0.109). These differences in Si content between plant organs are in line with other studies. For example, Si content was higher in Urtica dioica leaves than in stems, whereas it was the reverse in Phragmites australis (Struyf et al. 2005). Carey and Fulweiler (2013) found differences in Si contents in roots in the marsh species Spartina patens and Spartina alterniflora. Both species showed higher root Si content under high N availability (‘high-N marsh’) and lower root Si content under lower N availability (‘low-N marsh’). This seems to contradict with the findings of our study, yet we do not know whether ‘low N’ in the study by Carey and Fulweiler (2013) also corresponds to low N:P ratio. These studies and the results of our study indicate both species-specific and environment-specific differences of Si allocation across different plant organs. Clearly more research is needed to identify general Si allocation patterns under different environments. For example in our experiment, P limitation created the most stressful environment with the strongest effects on, for example, growth rates and biomass production. Additionally, under P limitation, silicification of plant tissue was more pronounced in leaves and stems, which reflected in higher Si:C ratios compared to the other treatments.

To evaluate further plant responses to nutrient availability, we measured total growth rate, biomass N:P ratio, root phosphatase (PME) activity, specific root length, chlorophyll content and root mass ratio (Fig. 3). Our results for these traits are in line with other studies about plant traits in relation to N and P limitation and support that the Holcus-plants in our experiment indeed faced N limitation, P limitation and balanced N:P supply. These studies, as well as our study describe a higher PME activity (Olde Venterink and Güsewell 2010) and greater root length/mass quotient (i.e. specific root length, White et al. 2013) under P limitation, as well as lower chlorophyll content under N limitation (Minden and Olde Venterink 2019). Also, total growth rate was stronger affected by P limitation than by N limitation (Fig. 3a). The growth rate hypothesis of Sterner and Elser (2002) states that higher growth rate is associated with higher P concentration and lower C∶P and N∶P ratios (Ågren 2008). As such, P deficiency has stronger effects on the growth rate of a species, and our results suggest that plants take up ‘low cost Si’ and assimilate less of ‘high cost C’ under these conditions. Related to growth, across plant functional types and phylogenetic groups, Cooke and Leishman (2011b) found leaf silicon content negatively correlated to leaf longevity, with shorter-lived leaves showing higher Si contents. They suggested that, considering Si to be metabolically cheaper than carbon, assimilated carbon could be invested in new leaf production, with positive effects on growth rates and they indeed observed positive correlations (albeit weak) among leaf Si with Nmass and SLA. These results, however, contradict our measured plant responses of higher Si allocation under stressful (nutrient) conditions, and a non-significant correlation between leaf Si and SLA (data not shown). Hence, comparing the results of Cooke and Leishman (2011b) to our results illustrates that the patterns between growth rate of plants and Si:C ratios appear to be different for comparisons within and among species.

There are studies in which observed correlations between plant contents of Si, C and nutrients were ascribed to limitations to C assimilation. For example, Schaller et al. (2012b) report significantly lower C and N concentrations, and higher P concentrations in leaf blades and culms of Phragmites australis under higher Si availabilities. Elevated silicon supply lead to silica deposition in the epidermis, which promoted altered N:P ratios. Neu et al. (2017) found a negative correlation of Si and C content, and a positive correlation of Si and P content in tissue of Triticum aestivum. This increase of the plant P status by Si was explained by a mobilization of P from strong binding to soil minerals by silicic acid increasing P availability for plants (Reithmaier et al. 2017; Schaller et al. 2019). A study of Reithmaier et al. (2017) further showed that silicic acid can also mobilize N from soils. The authors suggest that this may be a result from either Si competing for binding sites or from stronger reducing conditions. However, Neu et al. (2017) and Reithmaier et al. (2017) used pure peat to conduct their study, whereas we used pure quartz sand as other soil types would have confounded our nutrient treatments. As such, it is difficult to directly compare the results of our experiment to the abovementioned studies. The possibility of silicic acid mobilizing P in sandy substrate should be further investigated, although it was not very likely to be important for our sand that we specifically selected because it did not contain measurable amounts of P or N.

To conclude, our study is the first to quantify Si content in plants under N and P limitation, and we could show that Si uptake is higher and C assimilation is lower under nutrient limitation. As argued by Cooke and DeGabriel (2016), the role of Si in stress alleviation is not yet sufficiently appreciated by plant science. Our study delivers additional reasoning for a change in perception towards the functional role of this element (see also review by Katz 2019). More studies are needed in which variation in C-assimilation and photosynthesis rates in response to light and nutrient conditions are investigated in relation to Si uptake. Such studies might further elucidate the role of silicon in different concepts of trait-environment relationships (e.g. the leaf and the whole-plant economic spectrums, Freschet et al. 2010; Wright et al. 2004). Also, light should be shed on the aforementioned species-specific differences of Si accumulation, as the potential to accumulate Si is differently distributed across the plant kingdom (Mitani and Ma 2005), and this might be an additional source of variation in Si accumulation in response to environmental conditions. Finally, to explore silicification under nutrient deficiency it is necessary to determine which organic or C-containing compounds are affected by Si-containing compounds. Si correlates for example with cellulose, lignin and phenol content, depending on tissue function (Klotzbücher et al. 2018; Schaller et al. 2012a). It can further form a double layer between the cuticula and epidermis in leaves which augments the UV screening effects of phenolics built in the epidermis or epidermis near areas (Schaller et al. 2013) or, build into epidermal cells as biosilicified structures, reduce the heat load of leaves (Wang et al. 2005). Which precise effects silicon has on plants under nutrient limitation cannot be derived from our study as data describing the underlying mechanisms were not measured, yet, our results demonstrate clearly that, under nutrient stress, plant take up more of the non-essential element silicon and this is accompanied by a decrease of the essential element carbon.

Data availability

Data will be publicly available through the TRY repository (TRY.org) upon article publication.

Abbreviations

- Si:

-

Silicon

- C:

-

Carbon

- N:

-

Nitrogen

- P:

-

Phosphorus

- RGRTotal :

-

Relative Growth Rate of Total Biomass

- PME activity:

-

Root phosphomonoesterase activity

- SRL:

-

Specific Root Length

- RMR:

-

Root Mass Ratio

- SLA:

-

Specific Leaf Area

References

Ågren G (2008) Stoichiometry and nutrition of plant growth in natural communities. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 39:153–170. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173515

Allen SE (1989) Chemical analysis of ecological materials. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford

Andersen JM (1976) An ignition method for determination of total phosphorus in lake sediments. Water Res 10:329–331

Box GEP, Cox DR (1964) An analysis of transformations. J R Stat Soc 26:211–246

Cai KZ, Gao D, Luo SM, Zeng RS, Yang JY, Zhu XY (2008) Physiological and cytological mechanisms of silicon-induced resistance in rice against blast disease. Physiol Plant 134:324–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.2008.01140.x

Carey JC, Fulweiler RW (2013) Nitrogen enrichment increases net silica accumulation in a temperate salt marsh. Limnol Oceanogr 58:99–111. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2013.58.1.0099

Cebrián-Piqueras MA, Trinogga J, Grande C, Minden V, Maier M, Kleyer M (2017) Interactions between ecosystem properties and land use clarify spatial strategies to optimize trade-offs between agriculture and species conservation. International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services and Management 13:53–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/21513732.2017.1289245

Chambers JM, Freeny A, Heidberger RM (1992) Analysis of variance: designed experiments. In: Chambers JM, Hastie TJ (eds) Statistical models. Wadsworth & Brooks/Cole, Pacific Grove

Chen D, Cao B, Lingyun Q, Yin L, Shiwen W, Xiping D (2016) Silicon-moderated K-deficiency-induced leaf chlorosis by decreasing putrescine accumulation in sorghum. Ann Bot 118:305–315. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcw111

Cooke J, DeGabriel J (2016) Editorial: plant silicon interactions between organisms and the implications for ecosystems. Front Plant Sci 7:3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01001

Cooke J, Leishman MR (2011a) Is plant ecology more siliceous than we realise? Trends Plant Sci 16:61–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2010.10.003

Cooke J, Leishman MR (2011b) Silicon concentration and leaf longevity: is silicon a player in the leaf dry mass spectrum? Funct Ecol 25:1181–1188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2011.01880.x

Cornelis JT, Delvaux B (2016) Soil processes drive the biological silicon feedback loop. Funct Ecol 30:1298–1310. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12704

Coskun D, Britto DT, Huynh WQ, Kronzucker HJ (2016) The role of silicon in higher plants under salinity and drought stress. Front Plant Sci 7:1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01072

Coskun D, Deshmukh R, Sonah H, Menzies JG, Reynolds O, Feng Ma J, Kronzucker HJ, Bélanger RR (2019) The controversies of silicon’s role in plant biology. New Phytol 221:67–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15343

Craine JM (2009) Resource strategies of wild plants. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Craine JM, Fargione J, Sugita S (2005) Supply pre-emption, not concentration reduction, is the mechanism of competition for nutrients. New Phytol 166:933–940. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01386.x

DeMaster DJ (1981) The supply and accumulation of silica in the marine environment. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 45:1715–1732. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(81)90006-5

Dunbabin V, Diggle A, Rengel Z (2003) Is there an optimal root architecture for nitrate capture in leaching environments? Plant Cell Environ 26:835–844. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3040.2003.01015.x

Epstein E (1994) The anomaly of silicon in plant biology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91:11–17. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.91.1.11

Epstein E (2009) Silicon: its manifold roles in plants. Ann Appl Biol 155:155–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7348.2009.00343.x

Exley C (2015) A possible mechanism of biological silicification in plants. Front Plant Sci 6:7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.00853

Flam-Shepherd R, Huynh WQ, Coskun D, Hamam AM, Britto DT, Kronzucker HJ (2018) Membrane fluxes, bypass flows, and sodium stress in rice: the influence of silicon. J Exp Bot 69:1679–1692. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erx460

Fox J, Weisberg S (2019) An R companion to applied regression, third edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Fraysse F, Pokrovsky OS, Schott J, Meunier JD (2006) Surface properties, solubility and dissolution kinetics of bamboo phytoliths. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 70:1939–1951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2005.12.025

Freschet GT, Cornelissen JHC, van Logtestijn RSP, Aerts R (2010) Evidence of the 'plant economics spectrum' in a subarctic flora. J Ecol 98:362–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01615.x

Garnett T, Conn V, Kaiser BN (2009) Root based approaches to improving nitrogen use efficiency in plants. Plant Cell Environ 32:1272–1283. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02011.x

Güsewell S (2005a) High nitrogen: phosphorus ratios reduce nutrient retention and second-year growth of wetland sedges. New Phytol 166:537–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01320.x

Güsewell S (2005b) Responses of wetland graminoids to the relative supply of nitrogen and phosphorus. Plant Ecol 176:35–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-004-0010-8

Hattori T, Inanaga S, Araki H, An P, Morita S, Luxova M, Lux A (2005) Application of silicon enhanced drought tolerance in Sorghum bicolor. Physiol Plant 123:459–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.2005.00481.x

Hodson MJ, White PJ, Mead A, Broadley MR (2005) Phylogenetic variation in the silicon composition of plants. Ann Bot 96:1027–1046. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mci255

Hogan EJ, Minnullina G, Smith RI, Crittenden PD (2010) Effects of nitrogen enrichment on phosphatase activity and nitrogen: phosphorus relationships in Cladonia portentosa. New Phytol 186:911–925. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03222.x

Holdaway RJ, Richardson SJ, Dickie IA, Peltzer DA, Coomes DA (2011) Species- and community-level patterns in fine root traits along a 120 000-year soil chronosequence in temperate rain forest. J Ecol 99:954–963. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2011.01821.x

Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P (2008) Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom J 50:346–363

Hunt R (1990) Basic growth analysis. Unwin Hyman, London

Jaques WA (1974) Yorkshire fog (Holcus lanatus). Its potential as a pasture species. Proceedings of the New Zealand Grassland Association 36:249–257

Johengen T (1997) Standard operating procedures for determining total phosphorus, available phosphorus, and biogenic silica concentrations of Lake Michigan sediments and sediment trap material. In: Blume L (ed) Lake Michigan mass balance study (LMMB) methods compendium; volume 3 metals, conventionals, radiochemistry and biomonitoring sample analysis techniques. United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA 905R97012c)

Katz O (2019) Silicon content is a plant functional trait: implications in a changing world. Flora 254:88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flora.2018.08.007

Klotzbücher T, Klotzbücher A, Kaiser K, Vetterlein D, Jahn R, Mikutta R (2018) Variable silicon accumulation in plants affects terrestrial carbon cycling by controlling lignin synthesis. Glob Chang Biol 24:E183–E189. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13845

Kostic L, Nikolic N, Bosnic D, Samardzic J, Nikolic M (2017) Silicon increases phosphorus (P) uptake by wheat under low P acid soil conditions. Plant Soil 419:447–455

Ma JF, Takahashi E (2002) Soil, fertilizer, and plant silicon research in Japan. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Ma JF, Yamaji N (2015) A cooperated system of silicon transport in plants. Trends Plant Sci 20:435–442

Ma J, Cai HM, He CW, Zhang WJ, Wang LJ (2015) A hemicellulose-bound form of silicon inhibits cadmium ion uptake in rice (Oryza sativa) cells. New Phytol 206:1063–1074. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13276

Marschner H (2012) Mineral nutrition of higher plants. Academic, London

Mason B (1966) Composition of earth. Nature 211:616–618

Massey FP, Ennos AR, Hartley SE (2007) Grasses and the resource availability hypothesis: the importance of silica-based defences. J Ecol 95:414–424

McKeague JA, Cline MG (1963) Silica in soils. Adv Agron 15:339–396

McNaughton SJ, Tarrants JL, McNaughton MM, Davis RH (1985) Silica as a defence against herbivory and a growth promoter in African grasses. Ecology 66:528–535. https://doi.org/10.2307/1940401

Minden V, Olde Venterink H (2019) Plant traits and species interactions along gradients of N, P and K availabilities. Funct Ecol 33:1611–1626. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.13387

Minden V, Deloy A, Volkert AM, Leonhardt SD, Pufal G (2017) Antibiotics impact plant traits, even at small concentrations. Annals of Botany Plants 9:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/aobpla/plx010

Mitani N, Ma JF (2005) Uptake system of silicon in different plant species. J Exp Bot 56:1255–1261. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/eri121

Neu S, Schaller J, Dudel EG (2017) Silicon availability modifies nutrient use efficiency and content, C:N:P stoichiometry, and productivity of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Scientific Reports 7:8. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep40829

Olde Venterink H (2011) Does phosphorus limitation promote species-rich plant communities? Plant Soil 345:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-011-0796-9

Olde Venterink H, Güsewell S (2010) Competitive interactions between two meadow grasses under nitrogen and phosphorus limitation. Funct Ecol 24:877–886. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01692.x

O'Reagain PJ, Mentis MT (1989) Leaf silicification in grasses - a review. Journal of the Grassland Society of Southern Africa 6:37–43

Pavlovic J, Samardzic J, Kostic L, Laursen KH, Natic M, Timotijevic G, Schjoerring JK, Nikolic M (2016) Silicon enhances leaf remobilization of iron in cucumber under limited iron conditions. Ann Bot 118:271–280. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcw105

Pérez-Harguindeguy N, Díaz S, Garnier E, Lavorel S, Poorter H, Jaureguiberry P, Bret-Harte MS, Cornwell WK, Craine JM, Gurvich DE, Urcelay C, Veneklaas EJ, Reich PB, Poorter L, Wright IJ, Ray P, Enrico L, Pausas JG, de Vos AC, Buchmann N, Funes G, Quétier F, Hodgson JG, Thompson K, Morgan HD, ter Steege H, van der Heijden MGA, Sack L, Blonder B, Poschlod P, Vaieretti MV, Conti G, Staver AC, Aquino S, Cornelissen JHC (2013) New handbook for standardised measurement of plant functional traits worldwide. Aust J Bot 61:167–234. https://doi.org/10.1071/BT12225

Pilon-Smits EAH, Quinn CF, Tapken W, Malagoli M, Schiavon M (2009) Physiological functions of beneficial elements. Curr Opin Plant Biol 12:267–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2009.04.009

Piperno DR (2006) Phytoliths: a comprehensive guide for archaeologists and paleoecologists. Rowman and Littlefield, Oxford

Rasband W (2014) ImageJ, 1.46r. National Institutes of Health, USA

Raven JA (1983) The transport and function of silicon in plants. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 58:179–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.1983.tb00385.x

Reithmaier GMS, Knorr KH, Arnhold S, Planer-Friedrich B, Schaller J (2017) Enhanced silicon availability leads to increased methane production, nutrient and toxicant mobility in peatlands. Sci Rep 7:8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09130-3

Schaller J, Brackhage C, Dudel EG (2012a) Silicon availability changes structural carbon ratio and phenol content of grasses. Environ Exp Bot 77:283–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2011.12.009

Schaller J, Brackhage C, Gessner MO, Bauker E, Dudel EG (2012b) Silicon supply modifies C:N:P stoichiometry and growth of Phragmites australis. Plant Biol 14:392–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1438-8677.2011.00537.x

Schaller J, Brackhage C, Baucker E, Dudel EG (2013) UV-screening of grasses by plant silica layer? J Biosci (Bangalore) 38:413–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12038-013-9303-1

Schaller J, Schoelynck J, Struyf E, Meire P (2016) Silicon affects nutrient content and ratios of wetland plants. Silicon 8:479–485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-015-9302-y

Schaller J, Faucherre S, Joss H, Obst M, Goeckede M, Planer-Friedrich B, Peiffer S, Gilfedder B, Elberling B (2019) Silicon increases the phosphorus availability of Arctic soils. Sci Rep 9:11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-37104-6

Schoelynck J, Bal K, Backx H, Okruszko T, Meire P, Struyf E (2010) Silica uptake in aquatic and wetland macrophytes: a strategic choice between silica, lignin and cellulose? New Phytol 186:385–391. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03176.x

Sterner RW, Elser JJ (2002) Ecological stoichiometry: the biology of elements from molecules to the biosphere. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Struyf E, Van Damme S, Gribsholt B, Middelburg JJ, Meire P (2005) Biogenic silica in tidal freshwater marsh sediments and vegetation (Schelde estuary, Belgium). Mar Ecol Prog Ser 303:51–60. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps303051

The R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2019) RStudio, version 1.1.456. RStudio, Inc.

Thompson JD, Turkington R (1988) The biology of Canadian weeds. 82. Holcus lanatus L. Can J Plant Sci 68:131–147. https://doi.org/10.4141/cjps88-014

Van Bockhaven J, De Vleesschauwer D, Hofte M (2013) Towards establishing broad-spectrum disease resistance in plants: silicon leads the way. J Exp Bot 64:1281–1293. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ers329

Wang YX, Stass A, Horst WJ (2004) Apoplastic binding of aluminum is involved in silicon-induced amelioration of aluminum toxicity in maize. Plant Physiol 136:3762–3770. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.104.045005

Wang LJ, Nie Q, Li M, Zhang FS, Zhuang JQ, Yang WS, Li TJ, Wang YH (2005) Biosilicified structures for cooling plant leaves: a mechanism of highly efficient midinfrared thermal emission. Appl Phys Lett 87:194105. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2126115

Warton D, Wright EJ, Falster DS, Westoby M (2006) Bivariate line-fitting methods for allometry. Biol Rev 81:259–291. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1464793106007007

Warton D, Duursma RA, Daniel S, Taskinen S (2012) Smatr 3 - an R package for estimation and inference about allometric lines. Methods Ecol Evol 3:257–259

White PJ, George TS, Dupuy LX, Karley AJ, Valentine T (2013) Root traits for infertile soils. Front Plant Sci 4:1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2013.00193

Williams RJP, Fraústo da Silva JJR (1996) The natural selection of the chemical elements: the environment and Life's chemistry. Clarendon, Oxford

Wright IJ, Reich PB, Westoby M, Ackerly DD, Baruch Z, Bongers F, Cavenders-Bares J, Chapin T, Cornelissen JHC, Diemer M, Flexas J, Garnier E, Groom PK, Gulias J, Hikosaka K, Lamont BB, Lee T, Lee W, Lusk C, Midgley JJ, Navas M-L, Niinements Ü, Oleksyn J, Osada N, Poorter H, Poot P, Prior L, Pyankow VI, Roumet C, Thomas SC, Tjoelker MG, Veneklaas EJ, Villar R (2004) The worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Nature 428:821–827

Yandell BS (1997) Practical data analysis for designed experiments. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Martine Claeys for greenhouse support.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VM and HOV formulated the initial questions and designed the study. VM performed the greenhouse experiment and measured the plant traits. JS performed the analyses of silicon content in plant tissue. VM performed the statistical analyses. Writing was shared by all authors.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Hans Lambers.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 256 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Minden, V., Schaller, J. & Olde Venterink, H. Plants increase silicon content as a response to nitrogen or phosphorus limitation: a case study with Holcus lanatus. Plant Soil 462, 95–108 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-020-04667-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-020-04667-1