Abstract

In “Epistemic Modals,” Seth Yalcin argues that what explains the deficiency of sentences containing epistemic modals of the form ‘p and it might be that not-p’ is that sentences of this sort are strictly contradictory, and thus are not instances of a Moore-paradox as has been previous suggested. Benjamin Schnieder, however, argues in his Yalcin’s explanation of these sentences’ deficiency turns out to be insufficiently general, as it cannot account for less complex but still defective sentences, such as ‘Suppose it might be raining.’ Consequently, Schnieder proposes his own, expressivist treatment of epistemic modals which he thinks can explain the deficiency of both the original sentence type as well as more complex cases of embedded sentences containing epistemic modals. In this study, I argue that although Schnieder is right to draw our attention to the explanatory failure of Yalcin’s account, we aren’t forced to adopt Schnieder’s expressivist account of epistemic modals. I defend instead a contextualist-friendly alternative which explains the deficiencies of all the relevant sentence types, while avoiding both the defects of Yalcin’s account and the intuitive costs of expressivism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

If something in the neighborhood of knowledge, or at least belief, is a plausible candidate for the norm of assertion, that would explain why the joint assertion of both the conjuncts in (1) would be unwarranted. As Yalcin notes, the typical response to the Moore-paradox is to appeal to some pragmatic tension of this sort (Yalcin 2007, p. 984). Classical statements of this approach can be found in Hintikka (1962) and Unger (1975), although it has been discussed more recently in Stalnaker (2000) and Williamson (2000, Chap. 11).

In this study I concentrate on epistemic modals embedded ‘Suppose…' sentences, although there is surely a parallel story to tell for embeddings in the antecedents of conditional sentences. One reason we might expect similar results, which would also explain why (1a) and (1b) sound similarly unacceptable, would involve appeal to a suppositional theory of conditionals. For a nice treatment of this view, see Barnett (2006). The idea has also been suggested in different forms in Quine (1952), Mackie (1973), Dummett (1978) and Edgington (1995). I don't defend such a view in this article.

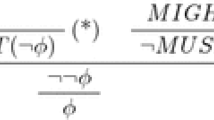

Yalcin goes on to work out a semantics for epistemic modals which yields this result. For the purposes of this study, it is not necessary to go into the details of his account.

Schnieder sometimes uses ‘perhaps' instead of ‘might'—e.g., ‘it is perhaps raining’—but ‘migh’ sounds more common to me, and I don't want our intuitions of deficiency to hinge on an atypical use of the modal.

Insofar as linguistic intuitions differ, such that one finds a sentence such as (4)—‘Suppose it might be raining’—to be acceptable, this may be due to one's hearing the sentence as having been spoken in a context or background in which a certain perspective, or body of information, is salient and to which the modal is implicitly relativized (e.g., the perspective of the audience). I say more about this in Sect. 3. We should also be careful not to hear (4) as either ‘Suppose it is raining’ or its older equivalent ‘Suppose it be raining’.

In addition, we shouldn't let conditional embeddings of epistemic modals sway our intuitions about the reliability of Schneider's data either, as in sentences like ‘If it might rain, we should take an umbrella’, or ‘If he might be the murder, then we should keep him in custody’. In both cases, the immediate use of ‘we’ is strong evidence that the modal is intended to be relativized to the shared evidence of whatever group of persons ‘we’ refers to in this context—which is in fact the reading we get.

Schnieder is not alone in proposing an expressivist treatment of epistemic modality. To mention only a few others who have advocated or explored the idea: Schroeder (2008); Swanson (forthcoming); and Yalcin (forthcoming).

This apparent egocentric reporting on our own epistemic states needn't, however, be explicit—which is a worry that Schnieder raises to motivate his expressivist theory (Schnieder 2010, p. 606), but which seems misplaced given that the typically tacit nature of this reporting ensures that the focus is on the content of our epistemic states. This is made clearer in Sect. 3 below, as are the ways in which epistemic possibilities can be relativized to other perspectives besides that of the speaker.

For those familiar with the study of Angelika Kratzer, the explanation might proceed along the following lines: the best interpretation of the modal in (1) is that it is raining is possible relative to (i.e., is not inconsistent with) a conversational background or modal base that contains the set of propositions consisting of what the speaker knows (or, perhaps, what the speaker believes). For a full statement of Kratzer's approach to modality, see Kratzer (1981), as well as Kratzer (1991).

For instance, I suspect that Schneider's view may run into potentially insoluble problems involving compositionality, though it is not my aim to definitively settle these long-running disputes here.

I want to remain neutral, however, as to whether such perspectives have to form part of the semantic content of ‘might’-sentences, as a standard contextualist view might have it, or whether pragmatic factors can play a significant role in the way a complete proposition gets communicated.

I want to distinguish this claim from a different one made by Schnieder, who argues that it is only assertable contents that are supposable (which I later argue is false), and thus, because only propositions are assertable, it follows that only propositions are supposable.

For a pair of plausible examples involving a conditional use of ‘might’, where ‘we' is used by the speaker to render salient the evidence of a particular group (see footnote 5).

Bach's view is importantly different from mainstream contextualist views of epistemic modality. One crucial issue is the way in which the truth of an assertion can “depend on” the context in which it is uttered. For Bach, the concrete context of an utterance is evidential, rather than determinative, of the way the proposition gets completed. Thus, Bach is not claiming that that ‘might' or ‘might'-sentences are context-sensitive, much less that ‘might'-sentences contain an implicit argument place that gets filled in by context. If, however, one wishes to reject Bach's view (for this or other reasons), a variety of contextualist views (e.g., Kratzer's view in footnote 8) have the resources to make the same argument, mutatis mutandis, against Yalcin and Schnieder.

Once again, as discussed in footnote 5 above, we should avoid letting our intuitions be swayed or driven by conditional embeddings, such as ‘If rotting carcases are tasty, we should see if they have any at the store.' As with similar sentences involving epistemic modals, the immediate occurrence of ‘we' in this sentence serves as evidence identifying the relevant standard of taste as that of the group ‘we' refers to, completing the proposition in a way that makes sense—unlike the supposition cases in (13a) and (14a).

Parallel behavior of various sorts between epistemic modals and predicates of personal taste has been noted elsewhere, including parallel difficulties in identifying the relevant perspective to which a might-claim or tasty-claim is relative. See, e.g., Stephenson (2007). Relativists about epistemic modals have likewise noted connections between the two (see Egan et al. 2005), and Schaffer (forthcoming) discusses related issues. No one, however, as far as I'm aware, has noted the similarity I point out here.

References

Bach, K. (forthcoming). Perspectives on possibilities: contextualism, relativism, or what? In A. Egan & B. Weatherson (Eds.), Epistemic modality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Barnett, D. (2006). Zif is If. Mind, 115, 519–565.

Dummett, M. (1978). Truth and other enigmas. London: Duckworth.

Edgington, D. (1995). On conditionals. Mind, 104, 235–330.

Egan, A., Hawthorne, J., & Weatherson, B. (2005). Epistemic modals in context. In G. Preyer & G. Peter (Eds.), Contextualism in philosophy: Knowledge, meaning, and truth (pp. 131–170). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hintikka, J. (1962). Knowledge and belief. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Kratzer, A. (1981). The notional category of modality. In H.-J. Eikmeyer & H. Rieser (Eds.), Words, worlds, and contexts. New approaches in word semantics (pp. 38–74). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Kratzer, A. (1991). Modality. In A. von Stechow & D. Wunderlich (Eds.), Semantik: Ein internationales handbuch zeitgenoessischer forschung (pp. 639–650). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Mackie, J. L. (1973). Truth, probability and paradox. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Quine, W. V. O. (1952). Methods of logic. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Schaffer, J. (forthcoming). Perspective in taste predicates and epistemic modals. In A. Egan & B. Weatherson (Eds.), Epistemic modality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schnieder, B. (2010). Expressivism concerning epistemic modals. The Philosophical Quarterly, 60, 601–615.

Schroeder, M. (2008). Being for: Evaluating the semantic program of expressivism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stalnaker, R. (2000). On ‘Moore’s paradox’. In P. Engel (Ed.), Believing and accepting. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Stephenson, T. (2007). Judge dependence, epistemic modals, and predicates of personal taste. Linguistic Philosophy, 30, 487–525.

Swanson, E. (forthcoming). How not to theorize about the language of subjective uncertainty. In A. Egan & B. Weatherson (Eds.), Epistemic modality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Unger, P. (1975). Ignorance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williamson, T. (2000). Knowledge and its limits. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Yalcin, S. (2007). Epistemic modals. Mind, 116, 983–1026.

Yalcin, S. (forthcoming). Nonfactualism about epistemic modality. In A. Egan & B. Weatherson (Eds.), Epistemic modality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Mark Schroeder, Steve Finlay, Alida Liberman, Ben Rohrs, Ben Lennertz, Tim Black and an anonymous reviewer for this Journal for many helpful and perceptive comments on earlier versions, as well as audiences at the Southern California Philosophy Conference and the Rocky Mountain Philosophy Conference for pressing me on several important points.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Crabill, J.D. Suppose Yalcin is wrong about epistemic modals. Philos Stud 162, 625–635 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-011-9785-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-011-9785-3