Abstract

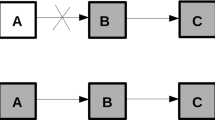

I argue that one central aspect of the epistemology of causation, the use of causes as evidence for their effects, is largely independent of the metaphysics of causation. In particular, I use the formalism of Bayesian causal graphs to factor the incremental evidential impact of a cause for its effect into a direct cause-to-effect component and a backtracking component. While the “backtracking” evidence that causes provide about earlier events often obscures things, once we our restrict attention to the cause-to-effect component it is true to say promoting (inhibiting) causes raise (lower) the probabilities of their effects. This factoring assumes the same form whether causation is given an interventionist, counterfactual or probabilistic interpretation. Whether we think about causation in terms of interventions and causal graphs, counterfactuals and imaging functions, or probability raising against the background of causally homogenous partitions, if we describe the essential features of a situation correctly then the incremental evidence that a cause provides for its effect in virtue of being its cause will be the same.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

There are Bayesian accounts of evidence that do not have this incrementalist character. See Joyce (2004) for relevant discussion.

Depending on the values of the variables, these chains can describe either promoting or inhibiting causes. For example, if C = {c, ¬c} and E = {e, ¬e} then a chain of arrows from C to E is consistent with c promoting e and inhibiting ¬e and with ¬c promoting ¬e and inhibiting e or with any other set of such causal relations.

A third condition of “Faithfulness” is often imposed, but this will not play any role in what follows.

Here and hereafter a lower case letter appearing in some probabilistic relationship will indicate a value of the variable. An upper case letter means that the relation holds for all the variable’s values.

Woodward (2005) is especially good on this point.

Lewis seeks to characterize these facts in non-causal terms. For purposes evaluating causal counterfactuals, worlds are similar when they agree about all particular facts until just before the cause occurs, and then agree afterword with respect to laws of nature. The occurrence of the cause is thus a “small miracle”. See Lewis (1979) for details.

If this seems counterintuitive, it helps to remind oneself that the only way that people who are not good looking can get into the department is by having a good sense of humor. Likewise, the only way people without a sense of humor can get in is by being good-looking. This explains the anti-correlation.

We can extend the approach described here to cases in which we know of a common cause Y of two correlated variables C and B, but not one that is detailed enough to fully screen-off the correlation. Here, we can block the backtracking inference by using Bayesian imaging on the partition of all conjunctions s & b, for s a value of S and b a value of B. This maneuver preserves the probabilities of all the S values and the probabilities of all the B values conditional on the S values, thereby preserving the probabilities of all the B values. Once again, the backtracking inference is blocked by the imaging method.

I do not mean to suggest that the equivalence of these three approaches has gone unnoticed. In fact, I think most experts in the field hold this view. The goal, rather, is to emphasize that all three approaches to causal reasoning produce exactly the same F and B functions, and thus the same basic epistemology of cause-to-effect inference.

References

Berkson, J. (1946). Limitations of the application of fourfold tables to hospital data. Biometrics Bulletin (now Biometrics), 2(3), 47–53.

Eells, E. (1991). Probabilistic causality. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Gärdenfors, P. (1982). Imaging and conditionalization. Journal of Philosophy, 79, 747–760.

Good, I. J. (1961). A causal calculus I. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 11, 305–318.

Good, I. J. (1962). A causal calculus II. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 12, 43–51.

Joyce, J. (1999). The foundations of causal decision theory. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Joyce, J. (2004). Bayesianism. In A. Mele & P. Rawling (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of rationality (pp. 132–155). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, D. (1973). Causation. Journal of Philosophy, 70, 556–567.

Lewis, D. (1979). Counterfactuals dependence and time’s arrow”. Nous, 13, 455–476.

Lewis, D. (2000). Causation as influence. Journal of Philosophy, 97, 182–197.

Pearl, J. (2000). Causality. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Reichenbach, H. (1956). The direction of time. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Skyrms, B. (1980). Causal necessity. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Skyrms, B. (1984). Pragmatics and empiricism. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Spirtes, P., Glymour, C., & Scheines, R. (1993). Causation. New York: Springer-Verlag, prediction and search.

Suppes, P. (1970). A probabilistic theory of causality. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company.

Woodward, J. (2005). Making things happen: A theory of causal explanation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Joyce, J.M. Causal reasoning and backtracking. Philos Stud 147, 139–154 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-009-9454-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-009-9454-y