Abstract

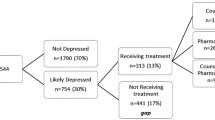

Background Diabetes distress (DD) has broad-ranging effects on type 2 diabetes (T2DM) management and outcomes. DD research is scarce among ethnic minority groups, particularly Arabic-speaking immigrant communities. To improve outcomes for these vulnerable groups, healthcare providers, including pharmacists, need to understand modifiable predictors of DD. Aim To assess and compare DD and its association with medication-taking behaviours, glycaemic control, self-management, and psychosocial factors among first-generation Arabic-speaking immigrants and English-speaking patients of Anglo-Celtic background with diabetes, and determine DD predictors. Setting Various healthcare settings in Australia. Method A multicentre cross-sectional study was conducted. Adults with T2DM completed a survey comprised of validated tools. Glycated haemoglobin, blood pressure, and lipid profile were gathered from medical records. Multiple linear regression models were computed to assess the DD predictors. Main outcome measure Diabetes distress level. Results Data was analysed for 696 participants: 56.3% Arabic-speaking immigrants and 43.7% English-speaking patients. Compared with English-speaking patients, Arabic-speaking immigrants had higher DD, lower medication adherence, worse self-management and glycaemic control, and poorer health and clinical profile. The regression analysis demonstrated that higher DD in Arabic-speaking immigrants was associated with cost-related medication underuse and lower adherence to exercise, younger age, lower education level, unemployment, lower self-efficacy, and inadequate glycaemic control. Whereas among English-speaking patients, higher DD was associated with both cost- and non-cost-related underuse of medication and lower dietary adherence. Conclusion Results provided new insights to guide healthcare providers on reducing the apparent excess burden of DD among Arabic-speaking immigrants and potentially improve medication adherence, glycaemic control, and self-management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data is available from the author by request.

References

Ogurtsova K, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Huang Y, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates for the prevalence of diabetes for 2015 and 2040. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;128:40–50.

Bommer C, Heesemann E, Sagalova V, et al. The global economic burden of diabetes in adults aged 20–79 years: a cost-of-illness study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(6):423–30.

Stark SC, Fradkin JE, Saydah SH, et al. The prevalence of meeting A1C, blood pressure, and LDL goals among people with diabetes, 1988–2010. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(8):2271–9.

Young-Hyman D, de Groot M, Hill-Briggs F, et al. Psychosocial care for people with diabetes: a position statement of the american diabetes association. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(12):2126–40.

Guo H, Wang X, Mao T, et al. How psychosocial outcomes impact on the self-reported health status in type 2 diabetes patients: findings from the diabetes attitudes, wishes and needs (DAWN) study in eastern China. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0190484.

Fisher L, Skaff MM, Mullan JT, et al. Clinical depression versus distress among patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(3):542–8.

Das-Munshi J, Stewart R, Ismail K, et al. Diabetes, common mental disorders, and disability: findings from the UK National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(6):543–50.

Fisher L, Hessler D, Glasgow RE, et al. REDEEM: a pragmatic trial to reduce diabetes distress. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(9):2551–8.

Fisher L, Hessler DM, Polonsky WH, et al. When is diabetes distress clinically meaningful?: establishing cut points for the diabetes distress scale. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(2):259–64.

Fisher L, Mullan JT, Arean P, et al. Diabetes distress but not clinical depression or depressive symptoms is associated with glycemic control in both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(1):23–8.

Chew B-H, Mohd-Sidik S, Shariff-Ghazali S. Negative effects of diabetes–related distress on health-related quality of life: an evaluation among the adult patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in three primary healthcare clinics in Malaysia. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:187.

van Dooren FEP, Nefs G, Schram MT, et al. Depression and risk of mortality in people with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos One. 2013;8(3):e57058.

Fisher L, Mullan JT, Skaff MM, et al. Predicting diabetes distress in patients with Type 2 diabetes: a longitudinal study. Diabet Med. 2009;26(6):622–7.

Polonsky WH, Anderson B, Lohrer P, et al. Assessment of diabetes-related distress. Diabetes Care. 1995;18(6):754–60.

Jannoo Z, Wah YB, Lazim AM, et al. Examining diabetes distress, medication adherence, diabetes self-care activities, diabetes-specific quality of life and health-related quality of life among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. J Cli Transl Endocrinol. 2017;9:48–54.

Maljanian R, Grey N, Staff I, et al. Improved diabetes control through a provider-based disease management program. Dis Manag Health Out. 2002;10:1–8.

Miller-Rosales C, Rodriguez HP. Interdisciplinary primary care team expertise and diabetes care management. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(1):151–61.

Campbell RK. Role of the pharmacist in diabetes management. Am J Health-system Pharmacy. 2002;59(Suppl 9):S18-21.

Rashid JR, Leath BA, Truman BI, et al. Translating comparative effectiveness research into practice: effects of interventions on lifestyle, medication adherence, and self-care for type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and obesity among black, hispanic, and asian residents of Chicago and Houston, 2010 to 2013. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2017;23(5):468–76.

Dieter T, Lauerer J. Depression or diabetes distress? Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2018;54(1):84–7.

Sturt J, Dennick K, Hessler D, et al. Effective interventions for reducing diabetes distress: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Diabet Nurs. 2015;12:40–55.

Schmidt CB, Potter van Loon BJ, Torensma B, et al. Ethnic minorities with diabetes differ in depressive and anxiety symptoms and diabetes-distress. J Diabet Res. 2017;2017:1204237.

Attridge M, Creamer J, Ramsden M, et al. Culturally appropriate health education for people in ethnic minority groups with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(9):CD006424.

Tenkorang EY. Early onset of type 2 diabetes among visible minority and immigrant populations in Canada. Ethn Health. 2017;22(3):266–84.

Alzubaidi H, Mc Narmara K, Kilmartin G, et al. The relationships between illness and treatment perceptions with adherence to diabetes self-care: a comparison between Arabic-speaking migrants and Caucasian English-speaking patients. Diabet Res Clin Pract. 2015;110(2):208–17.

Alzubaidi H, Mc Namara K, Browning C, et al. Barriers and enablers to healthcare access and use among Arabic-speaking and Caucasian English-speaking patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a qualitative comparative study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(11):e008687.

Alzubaidi H, Mc Mamara K, Chapman C, et al. Medicine-taking experiences and associated factors: comparison between Arabic-speaking and Caucasian English-speaking patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2015;32(12):1625–33.

Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24(1):67–74.

Aikens JE, Piette JD. Diabetic patients’ medication underuse, illness outcomes, and beliefs about antihyperglycemic and antihypertensive treatments. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(1):19–24.

Toobert D, Hampson S, Glasgow R. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:943–50.

Peterson PN, Shetterly SM, Clarke CL, et al. Health literacy and outcomes among patients with heart failure. JAMA. 2011;305(16):1695–701.

Chao J, Nau DP, Aikens JE, et al. The mediating role of health beliefs in the relationship between depressive symptoms and medication adherence in persons with diabetes. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2005;1(4):508–25.

Cherrington A, Wallston K, Rothman R. Exploring the relationship between diabetes self-efficacy, depressive symptoms, and glycemic control among men and women with type 2 diabetes. J Behav Med. 2010;33(1):81–9.

Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Earles J, et al. Assessing psychosocial distress in diabetes. Diabet Care. 2005;28(3):626–31.

Özcan B, Rutters F, Snoek FJ, et al. High diabetes distress among ethnic minorities is not explained by metabolic, cardiovascular, or lifestyle factors: findings from the dutch diabetes pearl cohort. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(9):1854–61.

Pousinho S, Morgado M, Falcão A, et al. Pharmacist interventions in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(5):493–515.

Armor BL, Britton ML, Dennis VC, et al. A review of pharmacist contributions to diabetes care in the United States. J Pharm Pract. 2010;23(3):250–64.

Pousinho S, Morgado M, Plácido AI, et al. Clinical pharmacists´ interventions in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Pharm Pract. 2020;18(3):2000.

Alsuwayni B, Alhossan A. Impact of clinical pharmacist-led diabetes management clinic on health outcomes at an academic hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: a prospective cohort study. Saudi Pharm J. 2020;28(12):1756–9.

Dennick K, Sturt J, Speight J. What is diabetes distress and how can we measure it? A narrative review and conceptual model. J Diabet Complicat. 2017;31(5):898–911.

Abuelezam NN, Abdulrahman ME-S, Galea S. The health of Arab Americans in the United States: an updated comprehensive literature review. Front Public Health. 2018;6:262.

Nguyen V, Tran T, Dang T, et al. Diabetes-related distress and its associated factors among patients with diabetes in Vietnam. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2020;13:1181–9.

Helgeson VS, Van Vleet M, Zajdel M. Diabetes stress and health: is aging a strength or a vulnerability? J Behav Med. 2020;43:426–36.

Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health. Sweden Institute for Futures Studies: Stockholm; 1991.

Mathiesen AS, Egerod I, Jensen T, et al. Psychosocial interventions for reducing diabetes distress in vulnerable people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Metab Syndr Obes. 2018;12:19–33.

Hoogendoorn CJ, Schechter CB, Llabre MM, et al. Distress and type 2 diabetes self-care: putting the pieces together. Ann Behav Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kaaa070.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank study participants for sharing their real views and experiences, and staff who supported recruitment at the participating study sites. Special thanks to Mr. Ward Saidawi for his outstanding efforts in data management.

Funding

This research was supported by an operational Grant from the University of Sharjah and an internal grant from the Centre for Medicine Use and Safety, Monash University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

Approval was obtained from the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (CF09/0956: 2009000462) and ethics committees at participating hospitals.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alzubaidi, H., Sulieman, H., Mc Namara, K. et al. The relationship between diabetes distress, medication taking, glycaemic control and self-management. Int J Clin Pharm 44, 127–137 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-021-01322-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-021-01322-2