Abstract

Background Optimum antihypertensive drug effect in chronic kidney disease is important to mitigate disease progression. As frequent adjustments to antihypertensive drugs might lead to problems that may affect their effectiveness, the modifiable factors leading to frequent adjustments of antihypertensive drugs should be identified and addressed. Objective This study aims to identify the factors associated with frequent adjustments to antihypertensive drugs among chronic kidney disease patients receiving routine nephrology care. Setting Nephrology clinics at two Malaysian tertiary hospitals. Method This multi-centre, retrospective cohort study included adult patients under chronic kidney disease clinic follow-up. Demographic data, clinical information, laboratory data and medication characteristics from 2018 to 2020 were collected. Multiple logistic regression was used to identify the factors associated with frequent adjustments to antihypertensive drugs (≥ 1 per year). Main outcome measure Frequent adjustments to antihypertensive drugs. Results From 671 patients included in the study, 219 (32.6%) had frequent adjustments to antihypertensive drugs. Frequent adjustment to antihypertensive drugs was more likely to occur with follow-ups in multiple institutions (adjusted Odds Ratio [aOR] 1.244, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.012, 1.530), use of traditional/complementary medicine (aOR 2.058, 95% CI 1.058, 4.001), poor medication adherence (aOR 1.563, 95% CI 1.037, 2.357), change in estimated glomerular filtration rate (aOR 0.970, 95% CI 0.951, 0.990), and albuminuria categories A2 (aOR 2.173, 95% CI 1.311, 3.603) and A3 (aOR 2.117, 95% CI 1.349, 3.322), after controlling for confounding factors. Conclusion This work highlights the importance of close monitoring of patients requiring initial adjustments to antihypertensive drugs. Antihypertensive drug adjustments may indicate events that could contribute to poorer outcomes in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Impacts on practice

-

Frequent adjustment of antihypertensive drugs was associated with follow-ups in multiple institutions

-

Use of traditional/complementary medicine

-

Poor adherence

-

eGFR changes

-

As well as albuminuria.

-

The factors associated with frequent antihypertensive drug adjustments could contribute to poorer outcomes of chronic kidney disease over time.

-

Close monitoring by pharmacists is recommended for patients requiring adjustments to antihypertensive drugs

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a global concern with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 9.1% [1]. Currently, there are no medications to treat the disease itself [2]. As such, CKD patients require multiple drugs to manage the various co-morbidities, to slow disease progression, and to mitigate complications [2, 3]. This gives rise to a substantially high medication burden, especially among advanced CKD patients, with some requiring more than 10 types of medication daily [2,3,4,5]. However, the use of more medications does not ensure a more positive clinical outcome. Therefore, optimisation of pharmacotherapy is vital for CKD patients, to ensure long-term effectiveness [6].

Adjustments to medications are an inevitable part of pharmacotherapy optimisation, to control risk factors of CKD progression, achieve therapeutic targets and accommodate changes in renal function [7]. Frequent adjustments to medications might indicate an underlying suboptimal disease control, poor control of CKD co-morbidities, or poor tolerance of current medication regimen, which are risk factors that predispose patients to CKD progression. However, some adjustments are preceded by preventable events, such as poor disease control due to medication non-adherence [7, 8]. There has been little research examining medication changes made during the treatment of long-term illnesses, due to difficulty retrieving complete data [3, 9]. Furthermore, patients may visit multiple institutions for follow-up on other conditions without complete reporting in medical records [3, 9].

Frequent adjustments to medications for patients with multiple medications can lead to various problems, including poor adherence, adverse effects and concerns about the new treatment [10]. These problems might be augmented in CKD patients with increased complexity to their medication regimens requiring patients to adapt to new routines, leading to other practical difficulties associated with medication changes [11]. Furthermore, the addition of medications increases the likelihood of receiving inappropriate medication, given the higher chance of drug-drug interactions among CKD patients who have an existing complex medication profile and altered pharmacokinetic profile [5, 12]. Frequent medication adjustments might also lead to harm if changes are not adhered to, such as unanticipated adverse events or drug interactions resulting from persistent use of medications that have been discontinued by the prescriber, or failure to achieve efficacy when the medicines were not adjusted as instructed [11].

Antihypertensive drug therapy is ubiquitous among CKD patients, due to hypertension being a common cause and consequence of CKD, and could improve outcomes and slow CKD progression [3, 13]. Optimised effect of antihypertensive drugs in CKD patients is important, as many antihypertensive drugs have multiple functions beyond blood pressure regulation, by mitigating hypertension-induced renal damage, reducing proteinuria and providing renoprotection [14]. Very often, antihypertensive drugs are changed due to uncontrolled blood pressure [14]. However, frequent changes may have a negative impact on the effectiveness of therapy. Therefore, other modifiable factors leading to frequent adjustments of antihypertensive drugs should be identified and prevented.

Aim of the study

The aim of this study was to identify factors associated with frequent adjustments to antihypertensive drugs among CKD patients receiving routine nephrology care.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the appropriate institutional and national research ethics committees, the Ministry of Health Medical Research and Ethics Committee (KKM.NIHSEC.P19-2320(11)) and the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Research Ethic Committee (JEP-2020-048). The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards specified in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Consent waiver was granted, due to the retrospective and non-interventional nature of the study.

Method

Study design

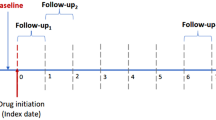

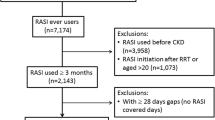

This multi-centre, retrospective cohort study was conducted in two tertiary hospitals with nephrology clinics. Included in the study were adult CKD patients (≥ 18 years) scheduled for a nephrology clinic follow-up during March and April 2020, with a history of at least 2 years of nephrology CKD clinic follow-up and prescribed at least one medication. Patients were excluded if they attended less than two nephrology CKD clinic visits between 2018 and 2020, and if their medication regimen was not recorded. Patients were identified and screened for eligibility based on data from electronic medical records and eligible patients were assigned using the IBM SPSS random number generator [15].

Sample size

A minimum sample size of 600 subjects was required, based on the estimation of n = 100 + 50(i), where ‘i’ refers to the number of independent variables in the final model, with an estimation of ten variables [16]. A total of 660 subjects were targeted to allow for possible exclusion of patients.

Data collection

Demographic data, clinical information, laboratory data and medication characteristics for each patient were collected from the electronic medical record systems. Demographic data that were collected included age, gender and ethnicity.

The clinical information included the primary cause of CKD, co-morbidities, including obesity (defined as body mass index (BMI) of ≥ 30 kg/m2) and smoking status. Co-morbidities were coded based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) [17]. The laboratory data collected were serum creatinine and albuminuria/proteinuria status during the study period. Patients’ renal function were quantified via estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), calculated using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation, and proteinuria status, categorised as per the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines [18]. Blood pressure was monitored by clinicians using an oscillometric device.

Details of the medication regimen were recorded for each patient visit during the study period, from the chartings of clinic visits and prescription records. The data collected were the number of adjustments to medications (including changes of drug, dose and frequency) and traditional/complementary medication (TCM) use. Medications used were recorded and coded in accordance with the World Health Organization Anatomical Therapeutic Classification (ATC) system [19]. Adherence to medication regimen was assessed using prescribers’ charting and prescriptions issued in the medical records.

Study definition

CKD classification and albuminuria categorisation were based on the eGFR level, as per the KDIGO CKD guidelines [18]. The definitions for each category are detailed in Table 1. Rapid progression of CKD was defined as a sustained decline in eGFR of more than 5 ml/min/1.73 m2/year [18].

Changes to antihypertensive drugs were categorised as minimal (less than once yearly) and frequent (at least once yearly) based on the median value [20], and included changes in dosage, frequency or cessation, or commencement of new antihypertensive drugs.

Adherence was considered to be poor if there was a discrepancy between the prescribers’ order and actual medication taken at any of the three phases of the medication adherence process [21]. The 2-year follow-up timeframe is consistent with a similar study on medication adherence [22].

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS [15]. The results were presented as frequencies and percentages for categorical data. Descriptive statistics for numerical data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data, or as median (range) for non-normally distributed data, based on the inspection of histograms. The correlation between antihypertensive drug adjustments and subsequent changes following initial adjustments (not normally distributed) was estimated via Spearman correlation coefficient. To identify the factors associated with frequent changes, multiple logistic regression was used. A univariate logistic regression was first performed to determine factors associated with frequent antihypertensive drug adjustments at a level of significance of p ≤ 0.05, followed by an examination of multicollinearity and correlation between the factors. A multiple stepwise logistic regression was then performed with factors with p ≤ 0.25. Variables with p ≤ 0.05 were considered factors associated with frequent adjustments to antihypertensive drugs [23]. The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, classification tables and area under the receiving operator characteristic (ROC) curve were examined to investigate any misrepresentation of data [24].

Results

Demographic data

A total of 671 patients were included in the study. There was a slight predominance of males (n = 379, 56.5%). The mean age was 61.4 ± 16.8 years (range 19–94 years). The ethnic distribution of the study sample was consistent with the demographic distribution of the population of Malaysia [25], with the highest cases recorded among Malays (n = 422, 62.9%), followed by Chinese (n = 183, 27.3%), Indians (n = 53, 7.9%), and others (n = 13, 1.9%). During the study period, 158 (23.5%) patients had uncontrolled blood pressure of > 130/80 mmHg [26].

Clinical information

Diabetes was the most common cause of CKD (n = 268, 39.9%), with similar proportions of patients with hypertension (n = 107; 15.9%) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE; n = 90; 13.4%) as the cause. Most patients had hypertension (n = 516, 76.9%), while almost half (n = 329, 49.0%) had diabetes. About one-quarter of patients (n = 163, 24.3%) had ischaemic heart disease or cerebrovascular diseases. Table 2 provides a summary of demographic and clinical information.

Renal function and level of albuminuria

At baseline, nearly half of the patients had an albuminuria category of A1 (n = 321, 47.8%), 139 (20.7%) in the A2 category, and the remainder in the A3 category (n = 211, 31.4%). Most patients were in Stage 3b (n = 182, 27.1%) or Stage 4 (n = 175, 26.1%) CKD (Table 2).

The mean eGFR declined by 3.1 ± 10.7 ml/min/1.73 m2 by the end of the study period. The eGFR improved in 125 (18.6%) patients, while 200 (29.8%) patients had a decline of not more than 5 ml/min/1.73 m2. There were 306 (45.6%) patients who had rapid CKD progression. Most of the 37 patients with renal replacement therapies (RRT) had existing RRT, while 11 (1.6%) developed end-stage renal disease (ESRD). The decline in the mean eGFR by the end of the study period was significantly greater among those with frequent changes to antihypertensive drugs (-6.1 ± 11.6 ml/min/1.73 m2) than those who had minimal changes to antihypertensive drugs (-2.9 ± 8.8 ml/min/1.73 m2) (p < 0.001).

Medication characteristics

Fifty-three (7.9%) patients reported taking TCM, while 41 (6.1%) patients used non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID)s. About one-third of patients had poor adherence to medications. The types of antihypertensive drugs at the baseline are illustrated in Fig. 1. Out of the 671 patients, 36.8% had an increase in their medications by the end of the study period. The frequency of adjustments to medications ranged from 0 to 51, with a median value of 3. Adjustment of antihypertensive drugs was the most common change (n = 948, 25.8%), followed by insulins (n = 388, 10.6%). The number of antihypertensive drug adjustments per patient ranged from 0 to 17, with a median value of 1. From the categorisation based on the median split, 219 (32.6%) patients had frequent adjustments to antihypertensive drugs, while the remaining 452 (67.4%) were classified as having minimal adjustments. A summary of the medication changes is provided in Table 3.

Types of antihypertensive agents used at baseline. a. Number of antihypertensive agents used at baseline. b Types of antihypertensive agents used by patients with a single antihypertensive. c Types of antihypertensive agents used by patients with two antihypertensive drugs. d Types of antihypertensive agents used by patients with three antihypertensive drugs. e Types of antihypertensive agents used by patients with four antihypertensive drugs. f Types of antihypertensive agents used by patients with five antihypertensive drugs. ACEI, Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, Angiotensin II Receptor blockers; BB, beta-blockers; CCB, Calcium channel blockers

The most common class of antihypertensive drug adjusted was calcium channel blockers (n = 288, 30.4%), followed by ACE inhibitors (n = 166, 17.5%), beta-blockers (n = 148, 15.6%) and ARBs (n = 143, 15.1%), as displayed in Table 4. Out of 671 patients, 310 (46.2%) had at least one adjustment made to their antihypertensive drugs and 158 (51.0%) of these patients had uncontrolled blood pressure of > 130/80 mmHg [26] when adjustment(s) were made. Thirty-three (10.6%) patients with antihypertensive drug adjustments had hyperkalaemia with serum potassium level of > 5 mmol/L.

Factors associated with frequent adjustments to antihypertensive drugs

A simple logistic regression analysis demonstrated that male gender, increasing number of follow-ups from various institutions, diabetic kidney disease, SLE, TCM use, poor adherence to medications, lower baseline eGFR, decline of eGFR during the study period and albuminuria categories of A2 and above, were factors associated with frequent antihypertensive drug adjustments with p < 0.05 (Table 5). When all variables with p-value of < 0.25 were included in the multiple logistic regression analysis, follow-ups from multiple institutions (adjusted Odds Ratio [aOR] 1.244, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.012, 1.530), TCM use (aOR 2.058, 95% CI 1.058, 4.001), poor adherence to medications (aOR 1.563, 95% CI 1.037, 2.357), change in eGFR during study period (aOR 0.970, 95% CI 0.951, 0.990), and albuminuria categories of A2 (aOR 2.173, 95% CI 1.311, 3.603) or A3 (aOR 2.117, 95% CI 1.349, 3.322) were found to be factors associated with frequent adjustments to antihypertensive drugs, after controlling for other confounding factors (Table 5).

Medication changes after adjustments to antihypertensive drugs

Fifty-six (18.1%) of the 310 patients reported subsequent antihypertensive medication changes following their initial adjustments, with most reasons being adverse effects of the antihypertensive drugs (n = 42, 75.0%). Uncontrolled hypertension was another reason for subsequent adjustments of medications (n = 11, 19.6%). In addition, a significant correlation was observed between adjustments to antihypertensive drugs and adjustments to other medications, such as antidiabetics (r = 0.207, p < 0.001), antiplatelets (r = 0.182, p < 0.001), lipid-modifying agents (r = 0.118, p < 0.001), gastrointestinal drugs (r = 0.143, p < 0.001), antianaemic drugs (r = 0.164, p < 0.001), immunosuppressants (r = 0.119, p = 0.002) and drugs for mineral-bone disease (r = 0.143, p < 0.001). The full list is available in supplementary material.

Discussion

Medication changes have rarely been studied, as medication use is commonly reported at one point in time [3, 9], and most studies have limited applicability to CKD patients because they were not CKD-specific [9, 27]. There is a vital need to track changes to medications, as they are associated with increased hospitalisation risk [27] and frequent adjustments may lead to confusion and errors in medication-taking, especially among CKD patients with complex medication regimens. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that has evaluated factors associated with frequent antihypertensive drug adjustments among CKD patients. The findings indicated that follow-up in multiple institutions, TCM use, poor adherence, declining eGFR and albuminuria are factors associated with frequent adjustments to antihypertensive drugs among CKD patients, which warrant additional attention to patients with such risk factors. These factors may also facilitate triaging of patients for ambulatory-care visits, especially in areas with limited resources and a high-volume of patients, or during the challenging times of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The association between frequent changes of antihypertensive drugs and multi-disciplinary follow-up warrants increased pharmacist care for such patients. Follow-ups with multiple disciplines might predispose patients to suboptimal adjustments to their medication regimen, based on inaccurate medication history and care transition errors, given that medication information is generally not shared between institutions [11]. Pharmacists could prevent such errors by performing medication reconciliation for patients who have multiple follow-ups and ensuring that accurate information on medications is well communicated to all prescribers [11].

The use of TCM might be driven by dissatisfaction with conventional treatments, as well as the belief that TCM have less adverse effects than conventional medicines [28]. TCM use among CKD patients is potentially hazardous, as the impairment of renal excretory functions predisposes patients to the risk of toxicity [29]. Drug responses might be altered with concurrent TCM ingestion, as evidenced by herb-drug interactions that attenuate antihypertensive drugs’ effects [29]. Furthermore, the pharmacokinetic properties of drugs with concurrent TCM use might be unpredictable, due to the presence of multiple bioactive constituents in various TCM used by CKD patients [29, 30]. There might be a greater need for drug adjustments in CKD patients following TCM use, due to drug-TCM interactions or acceleration of renal damage [29].

Poor adherence increases the risk of adverse events or medication efficacy loss, which then require frequent adjustments to, or intensification of medication regimen [8, 11]. Poor adherence is multifactorial [2, 4, 31, 32], with high medication burden and complex administration regimen often associated with poor adherence [32]. In addition, poor adherence is associated with poorer blood pressure control [4] and increased risk of CKD progression [4, 31], which ultimately lead to changes in medications.

It is not surprising that advanced baseline albuminuria and declining eGFR were found to be factors of frequent antihypertensive drug adjustments among CKD patients. Albuminuria is often a marker of cardiovascular disease risk and kidney damage, and a factor for rapid CKD progression [13, 18]. The involvement of various antihypertensive drugs in albuminuria management among CKD patients explains the more frequent adjustments of antihypertensive drugs for patients with greater albuminuria severity [13, 18]. In addition, the antihypertensive drugs were adjusted when eGFR declined, to slow renal disease progression [1, 13]. Moreover, frequent adjustments to antihypertensive drugs might be due to suboptimal medication effect, resulting from changes in pharmacokinetic parameters driven by a decline in the eGFR [7].

When adjusting antihypertensive drugs, it is important to balance the risks of adverse effects, without compromising the opportunity of enhanced therapeutic benefits in delaying the progression of CKD. However, about one-fifth of our patients had subsequent medication changes, suboptimal conditions and significant correlation with adjustments in other drugs following the change to antihypertensive drugs. Our findings warrant in-depth, long-term studies to draw conclusions on the overall health outcomes following frequent changes to antihypertensive drugs.

To that end, it is vital that CKD patients requiring their first change of antihypertensive drug be monitored closely for adherence, albuminuria and TCM use. The current work clearly demonstrates that those who require antihypertensive drug adjustment may be at risk of poor CKD control over time. Interestingly, this work demonstrates the need for pharmacists to strengthen CKD patient care, among those with antihypertensive drug adjustments, via monitoring their medication adherence, TCM use, albuminuria status, as well as education on correct medication knowledge, belief and management skills [31, 33]. Knowledge of CKD and treatment delays CKD progression and minimises CKD complications [2]. The potential benefits of pharmacist involvement are beyond the improvement of medication adherence, ranging from reduced hospitalisation rates to increased savings to healthcare systems [34].

This study is limited by its retrospective nature, such that causal inferences could not be drawn. As such, the outcomes of frequent adjustments to antihypertensive drugs are limited, due to the complexity of the various interactions between social, clinical and behavioural aspects. Irrespective of the causal mechanisms, we found a strong association between poor medication adherence, TCM use and frequent adjustments to antihypertensive drugs. In addition, poor adherence might have been underestimated by physicians, due to the lack of a structured work-up, as it is subject to recall and interviewer bias. The use of TCM and NSAID might have been underestimated, due to the retrospective nature of the study. Furthermore, host genetics in the dose–response relationship of antihypertensive drugs is a possible factor that was not examined and warrants verification in future research.

Conclusion

Medication management can be complex in patients with CKD. Given that the pharmacologic treatment of hypertension is an important consideration for CKD management, this work suggests enhanced monitoring of patients who require initial adjustments of antihypertensive drugs. The need to adjust antihypertensive drugs may be indicated by patients receiving follow-ups in multiple institutions, use of TCM, poor adherence, declining eGFR and albuminuria, all of which could eventually progress to poorer CKD outcomes.

References

Li PK, Garcia-Garcia G, Lui SF, Andreoli S, Fung WW, Hradsky A, et al. Kidney Health for Everyone, Everywhere-from prevention to detection and equitable access to care. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35:367–74.

Kadir TNITA, Islahudin F, Abdullah MZ, Ibrahim N, Bing PK. Assessing individual medication adherence among chronic kidney disease patients: a multi-centered study. J Pharm Res Int. 2019;31(4):1–11.

Schmidt IM, Hübner S, Nadal J, Titze S, Schmid M, Bärthlein B, et al. Patterns of medication use and the burden of polypharmacy in patients with chronic kidney disease: the German Chronic Kidney Disease study. Clin Kidney J. 2019;12:663–72.

Tangkiatkumjai M, Walker DM, Praditpornsilpa K, Boardman H. Association between medication adherence and clinical outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease: a prospective cohort study. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2017;21:504–12.

Laville SM, Metzger M, Stengel B, Jacquelinet C, Combe C, Fouque D, et al. Evaluation of the adequacy of drug prescriptions in patients with chronic kidney disease: results from the CKD-REIN cohort. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84:2811–23.

Ismail H, Abdul Manaf MR, Abdul Gafor AH, Mohamad Zaher ZM, Ibrahim AIN. Economic Burden of ESRD to the Malaysian Health Care System. Kidney Int Rep. 2019;4(9):1261–70.

Whittaker CF, Miklich MA, Patel RS, Fink JC. Medication safety principles and practice in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13:1738–46.

Kolandaivelu K, Leiden BB, O’Gara PT, Bhatt DL. Non-adherence to cardiovascular medications. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:3267–76.

Paterson C, Britten N. A narrative review shows the unvalidated use of self-report questionnaires for individual medication as outcome measures. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(10):967–73.

Barber N. Patients’ problems with new medication for chronic conditions. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(3):172–5.

Ibrahim J, Hazzan AD, Mathew AT, Sakhiya V, Zhang M, Halinski C, et al. Medication discrepancies in late-stage chronic kidney disease. Clin Kidney J. 2017;11:507–12.

Alhawassi TM, Krass I, Pont LG. Antihypertensive-related adverse drug reactions among older hospitalized adults. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40:428–35.

Sarafidis PA, Khosla N, Bakris GL. Antihypertensive therapy in the presence of proteinuria. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:12–26.

Griffin KA. Hypertensive kidney injury and the progression of chronic kidney disease. Hypertension. 2017;70:687–94.

Corp IBM. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. 23rd ed. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2015.

Bujang MA, Sa’at N, Sidik T, Joo LC. Sample size guidelines for logistic regression from observational studies with large population: emphasis on the accuracy between statistics and parameters based on real life clinical data. Malays J Med Sci. 2018;25(4):122–30.

World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases and Related Problems. (ICD-10 Version:2019) [Internet]. Geneva (CH): World Health Organization. 2019. [cited 2020 Dec 15]. https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en#/.

KDIGO WGC. KDIGO. Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2012(3):1–150.

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment 2020. Oslo: WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology; 2019. ISBN:978-82-8406-046-0

Iacobucci D, Posavac SS, Kardes FR, Schneider MJ, Popovich DL. Toward a more nuanced understanding of the statistical properties of a median split. J Consum Psychol. 2015;25:652–65.

Vrijens B, De Geest S, Hughes DA, Przemyslaw K, Demonceau J, Ruppar T, et al. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73:691–705.

Schmitt KE, Edie CF, Laflam P, Simbartl LA, Thakar CV. Adherence to antihypertensive agents and blood pressure control in chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2010;32:541–8.

Harrell Jr FE. Multivariable Modeling Strategies. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2015. ISBN:978-3-319-19425-7.

Hosmer DW J, Lemeshow S. Assessing the fit of the model. In: Hosmer DW J, Lemeshow S, editors. Applied Logistic Regression. Danvers: Wiley; 2000. p. 156–64. ISBN:0-471-35632-8.

Department Of Statistics Malaysia. Current Population Estimates, Malaysia, 2018–2019 [Internet]. Kuala Lumpur (MY): Department Of Statistics Malaysia. 2019. [cited 2020 Dec 15]. https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/pdfPrev&id=aWJZRkJ4UEdKcUZpT2tVT090Snpydz09.

Chang AR, Lóser M, Malhotra R, Appel LJ. Blood pressure goals in patients with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14:161–9.

Sino CGM, Stuffken R, Heerdink ER, Schuurmans MJ, Souverein PC, Egberts TACG. The association between prescription change frequency, chronic disease score and hospital admissions: a case control study. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;14(39).

Islahudin F, Shahdan IA, Mohamad-Samuri S. Association between belief and attitude toward preference of complementary alternative medicine use. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:913–8.

Dahl NV. Alternative Medicine and Nephrology Series Editor: Naomi V. Dahl: herbs and supplements in dialysis patients: panacea or poison? Semin Dial. 2001;14(3):186–92.

Muhammad Yusuf A, Abdul Gafor AH, Shamsul AS. The use of complementary and alternative medicine among Malaysian Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. Med Health. 2019;14(2):219–34.

Cedillo-Couvert EA, Ricardo AC, Chen J, Cohan J, Fischer MJ, Krousel-Wood M, et al. Self-reported medication adherence and CKD progression. Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3(3):645–51.

Seng JJB, Tan JY, Yeam CT, Htay H, Foo WYM. Factors affecting medication adherence among pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of literature. Int Urol Nephrol. 2020;52:903–16.

Ng YK, Shah NM, Loong LS, Pee LT, Hidzir SAM, Chong WW. Attitudes toward concordance and self-efficacy in decision making: a cross-sectional study on pharmacist-patient consultations. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:615–24.

Pai AB, Boyd A, Depczynski J, Chavez IM, Khan N, Manley H. Reduced drug use and hospitalization rates in patients undergoing hemodialysis who received pharmaceutical care: a 2-year, randomized, controlled study. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29:1433–40.

Siti ZM, Tahir A, Farah AI, Fazlin SM, Sondi S, Azman AH, et al. Use of traditional and complementary medicine in Malaysia: a baseline study. Complement Ther Med. 2009;17(5–6):292–9.

Midi H, Sarkar SK, Rana S. Collinearity diagnostics of binary logistic regression model. J Interdiscip Math. 2010;13:253–67.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for his permission to publish this article.

Funding

This study was funded by the Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia, under the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS/1/2019/SKK09/UKM/02/2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, F.Y., Islahudin, F., Makmor-Bakry, M. et al. Factors associated with the frequency of antihypertensive drug adjustments in chronic kidney disease patients: a multicentre, 2-year retrospective study. Int J Clin Pharm 43, 1311–1321 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-021-01252-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-021-01252-z