Abstract

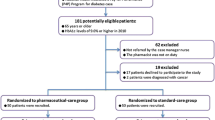

Background Physiological and psychological changes during puberty and a low adherence to complex treatment regimens often result in poor glycemic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). The benefit of pharmaceutical care in adults with diabetes mellitus type 2 has been explored; however, evidence in adolescents with T1DM is scarce. Objective To evaluate the impact of pharmaceutical care in adolescents with T1DM provided by pharmacists, in collaboration with physicians and diabetes educators on important clinical outcomes (e.g., HbA1c and severe hypoglycemia) Setting: At the outpatient Helios Paediatric Clinic and at the 12 regular community pharmacies of the study patients with 14 pharmacists in the Krefeld area, Germany, and at the University Pediatric Clinic with one clinical pharmacist on-site in Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina. Methods A randomized, controlled, prospective, multicenter study in 68 adolescents with T1DM. The intervention group received monthly structured pharmaceutical care visits delivered by pharmacists plus supplementary visits and phone calls on an as needed basis, for 6 months. The control group received usual diabetic care. Data were collected at baseline and after 3 and 6 months. Main outcome measures: The between-group difference in the change from baseline in glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and the number of severe hypoglycemic events in both groups. Results The improvement from baseline in HbA1c was significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group after 6 months (change from baseline −0.54 vs. +0.32 %, p = 0.0075), even after adjustment for country-specific variables (p = 0.0078). However, the effect was more pronounced after only 3 months (−1.09 vs. +0.23 %, p = 0.00002). There was no significant between-group difference in the number of severe hypoglycemia events. (p = 0.1276). Conclusion This study suggests that multidisciplinary PhC may add value in the management of T1DM in adolescents with inadequate glycemic control. However, the optimal methods on how to achieve sustained, long-term improvements in this challenging population require further study.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

The DIAMOD project group. Incidence and trends of childhood Type 1 diabetes worldwide 1990–1999. Diabet Med. 2006;23:857–66.

Patterson C, Dahlquist G, Gyürüs E, Green A, Soltész G. EURODIAB Study Group. Incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe during 1989–2003 and predicted new cases 2005–20: a multicentre prospective registration study. Lancet. 2009;373:2027–33.

Ehehalt S, Dietz K, Willasch AM, Neu A, Baden-Württemberg Diabetes Incidence Registry (DIARY) Group. Epidemiological perspectives on type 1 diabetes in childhood and adolescence in Germany. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:338–40.

Tahirovic H, Toromanovic A. Incidence of type 1 diabetes mellitus in children in Tuzla Canton between 1995 and 2004. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:491–2.

Daneman D, Hamilton J. Is poor metabolic control inevitable in adolescents with type 1 diabetes? An Pediatr. 2001;1:40–4.

Borus J, Laffel L. Adherence challenges in the management of type 1 diabetes in adolescents: prevention and intervention. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22:405–11.

Patino AM, Sanchez J, Eidson M, Delamater AM. Health beliefs and regimen adherence in minority adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30:503–12.

Schober E, Wagner G, Berger G, Gerber D, Mengl M, Sonnenstatter S, et al. Prevalence of intentional under-and overdosing of insulin in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2011;12:627.

Harjutsalo V, Forsblom C, Groop P. Time trends in mortality in patients with type 1 diabetes: nationwide population based cohort study. BMJ. 2011;343:5364.

Petersen M. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1033–46.

Daneman D. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 2006;367:847–58.

Wermeille J, Bennie M, Brown I, McKnight J. Pharmaceutical care model for patients with type 2 diabetes: integration of the community pharmacist into the diabetes team-a pilot study. Pharm World Sci. 2004;26:18–25.

Chisholm-Burns MA, Kim Lee J, Spivey CA, Slack M, Herrier RN, Hall-Lipsy E, et al. US pharmacists’ effect as team members on patient care: systematic review and meta-analyses. Med Care. 2010;48:923–33.

Machado M, Bajcar J, Guzzo GC, Einarson TR. Sensitivity of patient outcomes to pharmacist interventions. Part I: systematic review and meta-analysis in diabetes management. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1569–82.

Gay CL, Chapuis F, Bendelac N, Tixier F, Treppoz S, Nicolino M. Reinforced follow-up for children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes and inadequate glycaemic control: a randomized controlled trial intervention via the local pharmacist and telecare. Diabetes Metab. 2006;32:159–65.

Sims LM, Haines SL. Challenges of a pharmacist-directed peer support program among adolescents with diabetes. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2011;51:766–76.

Cipolle RJ, Strand LM, Morley PC. Pharmaceutical care practice: The clinician’s guide. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004.

van Mil JW, Schulz M, Tromp TF. Pharmaceutical care, European developments in concepts, implementation, teaching, and research: a review. Pharm World Sci. 2004;26(6):303–11.

Bosnia-Herzegovina Agency for Drugs and Medical Devices. Clinical trials [Agencija za lijekove i medicinska sredstva Bosne i Hercegovine]. http://www.almbih.gov.ba/klinicka-ispitivanja. Accessed 19 Sep 2014.

Bosnia-Herzegovina Agency for Drugsand Medical Devices. Clinical trial and medical devices directive of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Official Gazette of Bosnia and Herzegovina No. 4/10 [Sluzbeni Glasnik Bosne i Hercegovine Nr. 4/10 http://www.almbih.gov.ba/_doc/regulative/pravilnik_klinicka_bos.pdf. Accessed 19 Sep 2014.

Ineternational Society of Pediatric Diabetes. Clinical practice consensus guidelines 2009. http://www.ispad.org/content/ispad-clinical-practice-consensus-guidelines-2009. Accessed 19 Sep 2014.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–91.

Blume J, Peipert JF. Randomization in controlled clinical trials: why the flip of a coin is so important. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2004;11:320–5.

Berger W. A review of methods for ensuring the comparability of comparison groups in randomized clinical trials. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2006;1:81–6.

Clark M, Westerberg B. How random is the toss of a coin? CMAJ. 2009;181:306–8.

Viera A, Bangdiwala I. Eliminating bias in randomized controlled trials: Importance of allocation concealment and masking. Fam Med. 2007;39:132–7.

German National Treatment Guideline Program. Diabetes structured education program Version 3 Jun 2013 [Program fuer nationale Versorgungslinie, Diabetes strukturierteSchulungsprogramme].http://www.versorgungsleitlinien.de/themen/diabetes2/dm2_schulung/pdf/nvl-t2d-schulung-lang-3.pdf. Accessed 19 Sep 2014.

Workgroup on Hypoglycemia, American Diabetes Association. Defining and reporting hypoglycemia in diabetes: a report from the American Diabetes Association Workgroup on Hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(5):1245–9.

De Wit M, Pouwer F, Gemke RJ, Delemarre-van de Waal HA, Snoek FJ. Validation of the WHO-5 Well-Being Index in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2003–6.

WHO (Five) Well-Being Index (1998 version). Hillerod: Psychiatric Research Unit, WHO Collaborating Center for Mental Health, Frederiksborg General Hospital. 1998. http://www.psykiatri-regionh.dk/NR/rdonlyres/ACF049D6-C94D-49B2-B34C-96A7C5DA463B/0/WHO5_English.pdf. Accessed 19 Sep 2014.

R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2014. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Core Team Vienna, Austria: http://www.r-project.org. Accessed 19 Sep 2014.

American Diabetes Association. Management of dyslipidemia in children and adolescents with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2194–7.

Krass I, Armour CL, Mitchell B, Hughes J, Peterson G, Song YJ, et al. The Pharmacy Diabetes Care Program: assessment of a community pharmacy diabetes service model in Australia. Diabetic Med. 2007;24:677–83.

Mehuys E, Van Bortel L, De Bolle L, Van Tongelen I, Annemans L, Remon JP. Effectiveness of a community pharmacist intervention in diabetes care: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011;36:602–13.

Petkova V, Ivanova A, Petrova G. Education of patients with diabetes in the community pharmacies (pilot project in Bulgaria). Ankara Ecz Fak Derg. 2006;35:111–24.

Fresenius K. Impact of pharmaceutical care on clinical and therapy outcomes in patients with diabetic foot syndrom (DFS) [Dissertation]. Institute for Chemistry, Pharmacy and Geo-Science, University of Mainz, Germany: Fresenius K, 2007.

Pocock SJ. Clinical trials: a practical approach. Chichester: Wiley; 1995.

Gail M, Williams R, Byar DP, Brown C. How many controls? J Chronic Dis. 1976;29:723–31.

Dumville JC, Hahn S, Miles JN, Torgerson DJ. The use of unequal randomisation ratios in clinical trials: a review. Contemp Clin Trials. 2006;27:1–12.

Frank M. Psychological issues in the care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Paediatr Child Health. 2005;10:18–20.

Phan TL, Hossain J, Lawless S, Werk NL. Quarterly visits with glycated hemoglobin monitoring: The sweet spot for glycemic control in youth with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:341–5.

Kaufman FR, Halvorson M, Carpenter S. Association between diabetes control and visits to a multidisciplinary pediatric diabetes clinic. Pediatrics. 1999;103:948–51.

Svoren BM, Butler D, Levine BS, Anderson BJ, Laffel LM. Reducing acute adverse outcomes in youths with type 1 diabetes: A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2003;112:914–22.

The Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) study. Sustained effect of intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes mellitus on development and progression of diabetic nephropathy. JAMA 2003; 2159–2167.

van Mil JW, de Boer W, Tromp TH. European barriers to the implementation of pharmaceutical care. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 2001;9:163–8.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients. They also thank the participating pharmacists (in alphabetical order): Henrich Dieter Backes, Zora Bahser, Hans-Dieter Brink, Dieter Conze, Kathrin Furth, Klaus Dieter von Laguna, Anja Müller, Norbert Müller, Anne Rhein, Mara Scholz, Friederike Sieben, Ralf Weckop, Katja Weissenborn, and the pediatric clinic directors: Prof. Dr. med. Tim Niehues and Prof. Dr. med. Senka Mesihovic-Dinarevic. We are indebted to K. A. Lyseng-Williamson and L.Yang for editorial assistance.

Funding

Emina Obarcanin was financially supported by the Deutsche Akademische Auslandsdienst (DAAD), the Lesmüller Stiftung, and the Heinrich-Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany. The study was partially supported by the Lesmüller Stiftung.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Obarcanin, E., Krüger, M., Müller, P. et al. Pharmaceutical care of adolescents with diabetes mellitus type 1: the DIADEMA study, a randomized controlled trial. Int J Clin Pharm 37, 790–798 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-015-0122-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-015-0122-3