Abstract

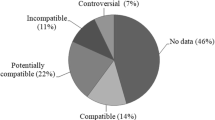

Objective Intravenous drug administration in neonatal (NICU) and paediatric intensive care units (PICU) is critical because of poor venous access, polymedication, fluid restriction and low infusion rate. Risk is further increased by inadequate information on the physicochemical compatibility of drugs. Eight decision-supporting tools were hence evaluated to improve the detection of drug incompatibilities in paediatric wards. Setting NICU and PICU, University hospital. Method Eight tools (Thériaque 2007, Stabilis 3, Perfysi 2 databases; KIK 3.0 software; Neofax 2007 handbook; King 2008Guide, CHUV 9.0, pH 2007 cross-tables) were assessed by two pharmacists using 40 drug pairs (20 incompatible; 20 compatible) frequently prescribed in PICUs and NICUs. Trissel’s 14th Ed. handbook served as the gold standard. Four criteria were evaluated (each with a maximum of 250 points): accuracy (sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values), completeness (number of drug pairs documented), comprehensiveness (presence of 16 different items), and applicability (by combining the time needed by 7 pharmacists to classify 5 drug pairs, plus an evaluation of their design, usefulness, reliability and ergonomics, using visual analogy scales). The percentage of non-compliant answers (NCA) was calculated for both the performing pharmacists and the tools. Main Outcome Measure Global score of drug incompatibilities (accuracy + completeness + comprehensiveness + applicability). ResultsThériaque obtained the best global score (840/1000 points), followed by pH (807), CHUV (803), Perfysi (776), Neofax (678), King Guide (642), Stabilis (584) and KIK (523), respectively. The highest scores were reached by Thériaque for accuracy (234/250); Thériaque and pH for completeness (200/250); Thériaque and Perfysi for comprehensiveness (218/250); and pH for applicability (298/250). The range of pharmacists’ NCAs was between 9% (4/45 NCAs) and 33% (15/45), whereas that for drug pairs was between 10% (6/63) and 30% (19/63). The range of NCAs for tools was between 6% (2/35, pH) and 49% (18/35, Perfysi). ConclusionsThériaque proved outstanding as a drug-incompatibility tool. However, all resources showed some shortcomings. The large ranges of pharmacists’ NCAs shows that such an assessment is subject to different interpretations. Standard operating procedures for drug-incompatibility assessment should be implemented in drug-information centres. Tools with low NCA percentage, such as the pH or CHUV tables, may be useful for nurses in ICUs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Appendix for calculation details.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

In order to scale the score of accuracy, completeness, comprehensiveness and applicability to 250 for the gold standard, correcting factors have been used.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

References

Kaushal R, Bates DW, Landrigan C, McKenna KJ, Clapp MD, Federico F, Goldmann DA. Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. JAMA. 2001;285(16):2114–20.

Simpson JH, Lynch R, Grant J, Alroomi L. Reducing medication errors in the neonatal intensive care unit. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89:F480–2.

Schneider MP, Cotting J, Pannatier A. Evaluation of nurses’ errors associated in the preparation and administration of medication in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pharm World Sci. 1998;20(4):178–82.

Monte SV, Prescott WA, Johnson KK, Huhman L, Paladino JA. Safety of ceftriaxone sodium at extremes of age. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2008;7(5):515–23.

Knowles JB, Cusson G, Smith M, Sitrin MD. Pulmonary deposition of calcium-phosphate crystals as a complication of home parenteral nutrition. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 1989;13:209–13.

Reedy JS, Kuhlman JE, Voytovich M. Microvascular pulmonary emboli secondary to precipitated crystals in a patient receiving total parenteral nutrition. Chest. 1999;115:892–5.

McNearney T, Bajaj C, Boyars M, Cottingham J, Haque A. Total parenteral nutrition associated crystalline precipitates resulting in pulmonary artery occlusions and alveolar granulomas. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48(7):1352–4.

Cuzzolin L, Atzei A, Fanos V. Off-label and unlicensed prescribing for newborns and children in different settings: a review of the literature and a consideration about drug safety. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2006;5(5):703–18.

De Giorgi I, Fonzo-Christe C, Bonnabry P. University of Geneva. January 2005. Sécurité de préparation et d’administration des médicaments en pédiatrie. [Security of preparation and administration of drugs in Paediatrics]. http://pharmacie.hug-ge.ch/ens/mas/diplome_idg.pdf (8 January 2009).

Zenk KE. Intravenous drug delivery in infants with limited IV access and fluid restriction. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1987;44:2542–5.

Leff R, Roberts RJ. Problems in drug therapy for pediatric patients. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1987;44:865–70.

Santeiro ML, Stromquist C, Coppola L. Guidelines for continuous infusion medications in the neonatal intensive care unit. Ann Pharmacother. 1992;26:671–4.

Fahimi F, Ariapanah P, Faizi M, Shafaghi B, Namdar R, Ardakani MT. Errors in preparation and administration of intravenous medications in the intensive care unit of a teaching hospital: an observational study. Aust Crit Care. 2008;21(2):110–6.

Wirtz V, Taxis K, Barber ND. An observational study of intravenous medication errors in the United Kingdom and in Germany. Pharm World Sci. 2003;25(3):104–11.

Taxis K, Barber N. Incidence and severity of intravenous drug errors in a German hospital. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;59:815–7.

Gikic M, Di Paolo ER, Pannatier A, Cotting J. Evaluation of physicochemical incompatibilities during parenteral drug administration in a paediatric intensive care unit. Pharm World Sci. 2000;22(3):88–91.

Trissel LA. Handbook on injectable drugs. 14th ed. Bethesda: American Society of Health System Pharmacy; 2007.

Di Paolo E, et al. Pharmacy of Lausanne’s University Hospital. Soins intensifs et continus de pédiatrie—Compatibilités des médicaments injectables administrés en Y. [Paediatric intensive and continuous care—Injectable drug compatibilities Y-admix] May 2006. http://files.chuv.ch/internet-docs/pha/medicaments/pha_compatibsipi_v9.pdf (8 January 2009).

Vogel Kahmann I, Bürki R, Denzler U, Höfler A, Schmid B, Splisgardt H. Inkompatibilitätsreaktionen auf der intensivstation [Incompatibility reactions in the intensive care unit. Five years after the implementation of a simple colour code system]. Anaesthesist. 2003;52:409–12.

Bensimon E. Perfysi v.2, ICHV, 12. 2007.

B∣Braun Medical AG. Kompatibilität Im Katheter 3.0 software Switzerland, 09.2002.

Infostab. http://www.stabilis.org/ Vigneron J, et al. Stabilis 3. CHU-Nancy, 11.2005.

Theriaque, http://www.theriaque.org/compatibilites/incompatibilites/home.cfm (Accessed February 1, 2010).

Young TE, Mangum B. Neofax. 20th ed. ISBN: 978-1-56363-672-1. Montvale: Thomson Healthcare, 2007.

Catania PN (Eds). KING Guide to parenteral admixtures. Wall chart. 2008.

Barrons R. Evaluation of personal digital assistant software for drug interactions. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2004;61:380–5.

Weingart SN, Toth M, Sands DZ, Aronson MD, Davis RB, Phillips RS. Physicians’ decisions to override computerized drug alerts in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(21):2625–31.

Vonbach P, Dubied A, Krähenbühl S, Beer JH. Evaluation of frequently used drug interaction screening programs. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30:367–74.

Bertsche T, Mayer Y, Stahl R, Hoppe-Tichy T, Encke J, Haefeli WE. Prevention of intravenous drug incompatibilities in an intensive care unit. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(19):1834–40.

International Journal of Pharmaceutical Compounding. The KING® Guide to Parenteral Admixtures®. CD-ROM 2008.

Huddleston J, Hay L, Everett JA. Patient-specific compatibility tables for the pediatric intensive care unit. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2000;57(24):2284–5.

Camut A, Noirez V, Gustin B, Khalife A. Amélioration des pratiques d’administration des antibiotiques injectables: proposition et évaluation d’un guide de compatibilité physico-chimique. [Improvement of antibiotics infusion practices: proposition and evaluation of a good practices’ guide]. J Pharm Clin. 2007;26(3):143–50.

Smith WD, Karpinski JP, Timpe EM, Hattoon RC. Evaluation of seven i.v. drug compatibility references by using requests from a drug information center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66:1369–75.

Trissel LA. Trissel’s 2 clinical pharmaceutics database [electronic database]. Cashiers, NC: Tripharma Communications. Updated regularly.

Müllerová H, Vlcek J. European drug information centres—survey of activities. Pharm World Sci. 1998;20:131–5.

Scala D, Bracco A, Cozzolino S, Cristinziano A, De Marino C, Di Martino A, et al. Italian drug information centres: benchmark report. Pharm World Sci. 2001;23:217–23.

UK Medicines Information. NHS; 11 January 2009. Medicines Information. Enquiry answering guidelines. UKMi. www.ukmi.nhs.uk/filestore/ukmiacg/Enquiryanseringguidelines2009.doc#_Toc224986466 (21 March 2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge all the pharmacists who took part in this study and the pharmacy of the CHUV, of the Central Institute of Valaisan Hospitals and of Schaffhausen’s Hospital for providing the tools they have developed. The authors thank Bernard Testa, Emeritus Professor, for his help in revising the article.

Funding

No financial support was received.

Conflicts of interest

None to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Sensitivity: The ability to correctly detect incompatibilities for drug pairs from I1 and I2 = Number of true positives/(number of true positives + number of false negatives) = Sen = TP/(TP + FN)

Specificity: The ability to ignore incompatibilities for drug pairs from C1 and C2 = Number of true negatives/(number of true negatives + number of false positives) = Spe = TN/(TN + FP)

Positive Predictive Value (PPV): The probability that, when the tool identified an incompatibility, it was an incompatibility defined as I1 or I2. = Number of true positives/(number of true positives + number of false positives) = PPV = TP/(TP + FP)

Negative Predictive Value (NPV): The probability that, when the tool ignored an incompatibility, it was a compatibility defined as C1 or C2. = Number of true negatives/(number of true negatives + number of false negatives) = NPV = TN/(TN + FN)

Accuracy score = (Sen + Spe + PPV + NPV) × 62.5Footnote 7

Completeness score = Number of drug pairs × 6.25Footnote 8

Comprehensiveness score = [Number of items/2.08] × [40/number of drug pairs]Footnote 9

Applicability score (adapted from Barrons [26]) = [1/(mean time needed to classify 5 drug pairs) × 1000/3.33] + [EVA(design) × 7.04] + [EVA(usefulness) × 5.44] + [EVA(reliability) × 5.32] + [EVA(ergonomics) × 6.49]Footnote 10

Global score = Accuracy score + Completeness score + Comprehensiveness score + Applicability score

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

De Giorgi, I., Guignard, B., Fonzo-Christe, C. et al. Evaluation of tools to prevent drug incompatibilities in paediatric and neonatal intensive care units. Pharm World Sci 32, 520–529 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-010-9403-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-010-9403-z