Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of the study was to construct a population pharmacokinetic model for pegylated liposomal doxorubicin and use the final model to investigate the discrimination performance of pharmacokinetic metrics (e.g., Cmax, AUC and partial AUC) of various analytes (e.g., liposome encapsulated doxorubicin, free doxorubicin and total doxorubicin) for the identification of formulation differences by means of Monte Carlo simulations.

Methods

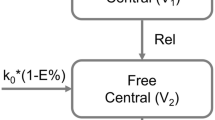

A model was simultaneously built to characterize the concentration time profiles of liposome-encapsulated doxorubicin and free doxorubicin using NONMEM. The different scenarios associated with changes in release rate (Rel) were simulated based on the final parameters. 500 simulated virtual bioequivalence (BE) studies were performed for each scenario, and power curves for the probability of declaring BE were also computed.

Results

The concentration time profiles of liposome-encapsulated doxorubicin and free doxorubicin were well described by a one- and two-compartment model, respectively. pAUC0-24 h and pAUC0-48 h of free doxorubicin was most responsive to changes in the Rel when the Rel (test)/Rel (reference) ratios decreased. In contrast, when the Rel (test) increased, AUC0-t of liposome-encapsulated doxorubicin was the most responsive metric.

Conclusions

In addition to the traditional metrics, partial AUC should be included for the BE assessment of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- AUC0-t :

-

Area under the curve up to last measurable time point

- BE:

-

Bioequivalence

- CLfree :

-

Clearance of the free doxorubicin

- CLres :

-

Uptake clearance of liposome-encapsulated doxorubicin by the reticuloendothelial system

- Cmax :

-

Maximum concentration

- CWRES:

-

Conditional weighted residuals

- E%:

-

Encapsulation percentage

- EMA:

-

European medicines agency

- FOCE:

-

First-order conditional estimation

- ICTRP:

-

International clinical trials registry platform

- IIV:

-

Inter-individual variability

- IV:

-

Intravenous

- IWRES:

-

Individual weighted residuals

- k0 :

-

Infusion rate

- l/h:

-

Liter per hour

- m2 :

-

Square meter

- mg/m2 :

-

Milligram per square meter

- ng/ml:

-

Nanogram per milliliter

- NONMEM:

-

Nonlinear mixed effects modeling

- pAUC:

-

Partial area under the curve

- Q:

-

Inter-compartmental clearance of the free doxorubicin

- Rel:

-

Release rate of the free doxorubicin from the liposome carrier

- RES:

-

Reticuloendothelial system

- RMSE:

-

Root mean square error

- TFDA:

-

Taiwan food and drug administration

- Tmax :

-

Time to maximum concentration

- USFDA:

-

United states food and drug administration

- V1:

-

Volume of distribution of the liposome-encapsulated doxorubicin

- V2:

-

Central volume of distribution of the free doxorubicin

- V3:

-

Peripheral volume of distribution of the free doxorubicin

- WfN:

-

Wings for nonlinear mixed effects modeling

References

Gabizon A, Shmeeda H, Barenholz Y. Pharmacokinetics of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin: review of animal and human studies. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42(5):419–36. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-200342050-00002.

Barenholz Y. Doxil®--the first FDA-approved nano-drug: lessons learned. J Control Release. 2012;160(2):117–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.03.020.

Drugs@FDA Website Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm Accessed 2 September 2017.

Taiwan Food and Drug Administration Website Available at: http://www.fda.gov.tw/MLMS/H0001.aspx Accessed 2 September 2017.

Kapoor M, Lee SL, Tyner KM. Liposomal drug product development and quality: current US experience and perspective. AAPS J. 2017;19(3):632–41. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-017-0049-9.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Draft Guidance for Industry: Doxorubicin HCl. Revised April 2017. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/.../Guidances/UCM199635.pdf Accessed 2 September 2017.

European Medicines Agency. Reflection paper on the data requirements for intravenous liposomal products developed with reference to an innovator liposomal product. Final February 2013. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2013/03/WC500140351.pdf. Accessed 2 September 2017.

Hsu LF, Huang JD. A statistical analysis to assess the most critical bioequivalence parameters for generic liposomal products. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;52(12):1071–82. https://doi.org/10.5414/cp202129.

Dosne AG, Bergstrand M, Karlsson MO. A strategy for residual error modeling incorporating scedasticity of variance and distribution shape. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2016;43(2):137–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10928-015-9460-y.

Drummond DC, Noble CO, Hayes ME, Park JW, Kirpotin DB. Pharmacokinetics and in vivo drug release rates in liposomal nanocarrier development. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97(11):4696–740. https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.21358.

Macheras P, Iliadis A. Modeling in biopharmaceutics, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: homogeneous and heterogeneous approaches. In: Karalis V, editor. Modeling and simulation in bioequivalence. 2rd ed. Switzerland: Springer; 2016. p. 227–54.

Sm A, S S. Bioequivalence Study of Pegylated Doxorubicin Hydrochloride Liposome (PEGADRIA) and DOXIL® in Ovarian Cancer Patients: Physicochemical Characterization and Pre-clinical Studies. J Nanosci Nanotechnol 2016;07(02). https://doi.org/10.4172/2157-7439.1000361.

Zhang X, Lionberger RA. Modeling and simulation of biopharmaceutical performance. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;95(5):480–2. https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.2014.40.

Zhang X, Duan J, Kesisoglou F, Novakovic J, Amidon GL, Jamei M, et al. Mechanistic oral absorption modeling and simulation for formulation development and bioequivalence evaluation: report of an FDA public workshop. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2017;6(8):492–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp4.12204.

Hussaarts L, Muhlebach S, Shah VP, McNeil S, Borchard G, Fluhmann B, et al. Equivalence of complex drug products: advances in and challenges for current regulatory frameworks. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2017;1407:39–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13347.

Fourie Zirkelbach J, Jackson AJ, Wang Y, Schuirmann DJ. Use of partial AUC (PAUC) to evaluate bioequivalence--a case study with complex absorption: methylphenidate. Pharm Res. 2013;30(1):191–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-012-0862-x.

Jackson A. Impact of release mechanism on the pharmacokinetic performance of PAUC metrics for three methylphenidate products with complex absorption. Pharm Res. 2014;31(1):173–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-013-1150-0.

Amantea MA, Forrest A, Northfelt DW, Mamelok R. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pegylated-liposomal doxorubicin in patients with AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1997;61(3):301–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0009-9236(97)90162-4.

Wu H, Ramanathan RK, Zamboni BA, Strychor S, Ramalingam S, Edwards RP, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of pegylated liposomal CKD-602 (S-CKD602) in patients with advanced malignancies. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52(2):180–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091270010394851.

Wu H, Infante JR, Keedy VL, Jones SF, Chan E, Bendell JC, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of PEGylated liposomal CPT-11 (IHL-305) in patients with advanced solid tumors. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(12):2073–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-013-1580-y.

Allen TM, Hansen C. Pharmacokinetics of stealth versus conventional liposomes: effect of dose. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1068(2):133–41.

Zamboni WC. Liposomal, nanoparticle, and conjugated formulations of anticancer agents. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(23):8230–4. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-05-1895.

Kontny NE, Wurthwein G, Joachim B, Boddy AV, Krischke M, Fuhr U, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of doxorubicin: establishment of a NONMEM model for adults and children older than 3 years. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71(3):749–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-013-2069-1.

Yu Y, Desjardins C, Saxton P, Lai G, Schuck E, Wong YN. Characterization of the pharmacokinetics of a liposomal formulation of eribulin mesylate (E7389) in mice. Int J Pharm. 2013;443(1–2):9–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.01.010.

Nageeb El-Helaly S, Abd Elbary A, Kassem MA, El-Nabarawi MA. Electrosteric stealth Rivastigmine loaded liposomes for brain targeting: preparation, characterization, ex vivo, bio-distribution and in vivo pharmacokinetic studies. Drug Deliv. 2017;24(1):692–700. https://doi.org/10.1080/10717544.2017.1309476.

Hu D, Onel E, Singla N, Kramer WG, Hadzic A. Pharmacokinetic profile of liposome bupivacaine injection following a single administration at the surgical site. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33(2):109–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-012-0043-z.

Lee LH, Choi C, Gershkovich P, Barr AM, Honer WG, Procyshyn RM. Proposing the use of partial AUC as an adjunctive measure in establishing bioequivalence between deltoid and gluteal Administration of Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2016;41(6):659–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13318-016-0348-z.

Lyass O, Uziely B, Ben-Yosef R, Tzemach D, Heshing NI, Lotem M, et al. Correlation of toxicity with pharmacokinetics of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil) in metastatic breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;89(5):1037–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(20000901)89:5<1037::AID-CNCR13>3.0.CO;2-Z.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s personal opinions and do not necessarily reflect the recommendations of the Taiwan CDE.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hsu, Lf. Investigation of the Discriminatory Ability of Pharmacokinetic Metrics for the Bioequivalence Assessment of PEGylated Liposomal Doxorubicin. Pharm Res 35, 106 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-018-2387-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-018-2387-4