Abstract

Global mobility and economic and political crises in some parts of the world have fuelled migration and brought new constellations of ‘cultural diversity’ to European classrooms (OECD 2019). This produces new challenges for teaching, but also for assessment in which cultural biases may have far-reaching consequences for the students’ further careers in education, occupation and life. After considering the concept of and current research on ‘culturally responsive assessment’, we use qualitative interview data from 115 teachers and school leaders in 20 lower secondary schools in Austria, Ireland, Norway and Turkey to explore the thinking about diversity and assessment practices of teachers in the light of increasing cultural diversity. Findings suggest that ‘proficiency in the language of instruction’ is the main dimension by which diversity in classrooms is perceived. While there is much less reference to ‘cultural differences’ in our case studies, we found many teachers in case schools trying to adapt their assessment procedures and grading in order to help students from diverse backgrounds to show their competencies and to experience success. However, these responses were, in many cases, individualistic rather than organised by the school or regional education authorities and were also strongly influenced and at times, limited by government-mandated assessment regimes that exist in each country. The paper closes with a series of recommendations to support the further development of a practicable and just practice of culturally responsive assessment in schools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction and background

Consistent with changing patterns of migration and the belief that school systems have a significant role to play in responding to ‘increasing social heterogeneity’ (OECD 2009, p. 3), many education systems have developed policy solutions and initiatives for the creation of culturally responsive classrooms (Ford and Kea 2009). As stated by the United Nations (UN), education systems around the world should be united in the commitment to ‘ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all’ (UN 2016). Providing cause for optimism, the 2018 TALIS report indicates that strategies on how to deal with ethnic and cultural discrimination are taught in 80% of the participating schools. On the other hand, giving cause for concern, more than 50% of teachers in the participating countries did not feel well-prepared for the challenges of a multicultural learning environment and were not confident in adapting their teaching to the cultural diversity of students (OECD 2019, pp. 98).

However, it is not only teaching that offers potential pitfalls for migrant students aiming to achieve to their full potential. There are other connected practices such as assessment that, according to Arbuthnot (2017) among others, need to be considered in all learning environments, as assessment has the potential to act as a powerful catalyst to improve teaching and learning (Hattie 2009) and in most countries also opens up entry to further education and employment (Black and Wiliam 2012; Shepard 2006; Popham 2009). In addition, for migrant students, there is also a historical and cultural dilemma that needs to be overcome, as the dominant modes of assessment, together with the assessment competencies of teachers, are also, by tradition, linked with the cultural, historical and political agendas that exist in migrant-receiving countries and can have a positive or negative effect on student learning (Crichton 1998; Isaacs 2010; LeMétais 2003). Analysis of PISA test scores in mathematics, for example, reveals that students with the same migration background perform differently in some OECD countries compared to others, even when indicators that affect student performance such as socioeconomic status are considered (OECD 2016). In other words, the assessment regimes that exist in different countries can, in some way, have a corollary effect on student achievement, indicating a need to re-examine the effects of assessment regimes on classroom practice (Brown 2007).

The initial conceptualisation for this research—which was part of a three-year European Union-funded project entitled Aiding Culturally Responsive Assessment in Schools (ACRAS) [1] [1] ERASMUS+-Project 'Aiding Cultural Responsive Assessment in Schools' (ACRAS; 2016-1-IE01-KA201-016889)—came from studying how teachers cope with and adapt to the assessment needs of culturally diverse classrooms. A review of the research on teaching, learning, assessment and diversity revealed that there is a body of literature concerning the educational needs of students not belonging to the respective mainstream culture and about responsive pedagogies aiming to enhance their learning. Such issues have until now been more widely studied in North America and other English-speaking countries than in other European countries (Nortvedt et al. 2020). Most of the previous research and conceptual work seems to focus on the implications of cultural and linguistic diversity for teaching and learning, rather than on assessment. So, we find empirical studies of teaching and learning in different subjects and of different minority groups (e.g. Gutiérrez 2002; Schleppegrell 2007; Lesaux et al. 2014), proposals for culturally responsive teaching (e.g. Aceves and Orosco 2014; Gay 2010; Ladson-Billings 1995a, b; 2014) and the role of school culture in providing a climate for students where they can experience educational equality and cultural empowerment (Banks and Banks 2004). Moreover, there are studies indicating approaches for student-centred pedagogy more generally and responsiveness towards children’s contribution in joint activities (Brook Chapman de Sousa 2017) and emphasising preparation for culturally responsive and inclusive practices as part of teacher education (Warren 2017; Young 2010). In this paper, we cannot do justice to the entire literature on culturally and linguistically responsive teaching but will focus (in the next section) on the much smaller body of research on assessment under conditions of cultural diversity.

In Europe, with some exceptions (e.g. Mitakidou et al. 2015), there is only a limited number of studies that have specifically explored the challenges relating to the assessment of migrant students as perceived by teachers. To fill the lacuna of research, the current study sought to explore: aspects of diversity that teachers in European classrooms attend to in assessment situations, the strategies that teachers use in assessment to take account of diversity, and the supportive and inhibiting conditions encountered by teachers when adapting to diversity in their approaches to assessment. While there are huge differences between European countries with respect to the amount and history of their diversity and with respect to the characteristics of their education systems, Europe may offer the opportunity to study a type of cultural and linguistic diversity in education which is different from the one found in North America, i.e. with respect to the number and diversity of newly immigrated, displaced refugees.

The countries participating in this study differ widely with regard to the proportion of migrants in their schools. Austria has the highest average share of students (25.3%) with first languages other than the language of instruction (Statistik Austria 2017). In Ireland and Norway, the percentage is between 8 and 15% (Eurostat 2017). Whilst no official figures are available for the total proportion of migrant students in Turkey, as a result of the political crisis in Syria, of the 4 million Syrian refugees that currently reside in Turkey, approximately 1.7 million are children of which 645,000 are enrolled in schools (UNICEF 2018). Additionally, different types of governance in education are in place in the four countries: While Austria, Ireland and Turkey represent a model of ‘State-Based Governance’ with high levels of bureaucracy and little school autonomy (Windzio et al. 2005, p. 11–16), Norway has a school system which is characterised by a relatively high degree of local autonomy (Telhaug et al. 2006; or in Windzio et al.’s terms: a ‘Scandinavian Governance’).

The first section of this paper describes the different uses and potential implications of assessment, which is followed by an analysis of proposed solutions for the assessment of migration background students. Then, the methodology used in the study is described. The penultimate section provides an analysis of the research findings derived from a series of case studies on assessment practices in 20 lower secondary schools in the four countries. The paper concludes with a discussion of the research findings and implications for further action in the field of assessment and cultural diversity.

2 Assessment and cultural diversity in education

Assessment is one of the basic building blocks of institutionalised schooling. At the classroom level, it can be used formatively to enhance learning (Hattie 2009) and to improve teaching (Black and Wiliam 2012; Shepard 2006). However, assessment can also be used to make distinctions in a field of diverse performances and, either through teachers or through externally devised assessments or a combination of both, can be used to sort students for future education or working life (Eder et al. 2009).

The modern ‘meritocratic’ type of schooling is built on the idea that learning opportunities, results and certificates must not be distributed according to social class, economic power, religious denomination, and gender, but solely through a fair appreciation of actual performance (Fend 2009). Nevertheless, research shows that this idea of equity is not fulfilled in many cases and that in reality, the grades of students are correlated to categories of social background (Alcott 2017). This is also true for language and culture aspects: assessment performance and grades are impaired when the assessment language is not the first language of the student (Nusche et al. 2009; Padilla 2001). In many cases, assessment practices seem to be in place which deny students the opportunity to achieve their true potential (Brown-Jeffy and Cooper 2011). This is because teachers may not have acquired the professional capacity to adapt assessments to the needs of migration background students (Nayir et al. 2019) or because there is a limited range of appropriate assessment tasks and support structures available (Castagno and Brayboy 2008; Espinosa 2005).

In order to ensure equity of assessment for students coming from non-mainstream cultures or migrant families, assessment should be ‘culturally responsive’ (Hood 1998a, b; Hood et al. 2015; Arbuthnot 2017; Brown et al. 2019). A range of assessment methods that provide additional opportunities for students to demonstrate their learning have been proposed. These include creativity assessment (Kim and Zabelina 2015), dynamic assessment (Lidz and Gindis 2003), performance-based assessment (Baker et al. 1993), peer assessment (Topping 2009) and self-assessment (Taras 2010, p. 606). Culturally responsive assessment practices are also characterised by being student-centred and focusing on ways in which students can contribute using their previous knowledge and experiences in the assessment situation. In doing so, they are narrowing the gap between instruction and assessment situations, as e.g. in assessment for learning (Black and Wiliam 2012), which is frequently recommended as an element of a culturally responsive assessment strategy.

The issue of enhancing culturally responsive practices does not relate solely to the provision of extra resources and training. According to Thompson-Robinson et al. (2004), at a conceptual level, the challenges ‘remain complex, multi-faceted, and context-rich’ (p. 3). Indeed, the literature suggests that for teachers to be serious about being culturally responsive assessors, they also need to be researchers of their own culture and professionalism. This perspective resonates with the American Evaluation Association’s (2011) statement on cultural competence: ‘Cultural competence is not a state at which one arrives; rather, it is a process of learning, unlearning, and relearning’ (p. 13). This is a daunting task, requiring the professional teacher to reflect on practice in an in-depth manner. As a consequence, the role of a ‘culturally responsive assessor’ seems to converge with that of a ‘reflective practitioner’ (Schön 1983) ‘becoming aware of the limits of our knowledge, of how our own behaviour plays into organisational practices and why such practices might marginalise groups or exclude individuals’ (Bolton 2010, p. 14). Culturally responsive teachers are challenged to be aware of cultural and social diversities, to embed culturally sensitive approaches in their practices (Ford and Kea 2009), and to monitor and develop their practices in this respect (Feldman et al. 2018).

Nonetheless, teachers can find it difficult to respond positively to the demands of culturally diverse educational contexts (Torrance 2017). Culturally responsive assessment strategies can act as a powerful catalyst for effective classroom practice. However, while schools and teachers have a responsibility for the implementation of these practices, they are also dependent on and limited by the assessment policies and regulations that allow for the flourishing of such innovations (Burns et al. 2017). To concur with Schapiro (2009), it is necessary to question whether education policies do in fact ‘improve the student’s access to quality education, stimulate equitable participation in schooling, and lead to learning outcomes at par with native peers’ (p. 33), or conversely restrict and inhibit the ability of schools and teachers to respond imaginatively and generously to new realities.

While many European classrooms, particularly in bigger cities, have been culturally diverse for decades (Crul et al. 2012), others have become vastly and quite suddenly more diverse in recent years. Yet, there is little research so far on the actual practices and conditions of assessment in these contexts. Thus, our study was conceived to explore how teachers in European countries cope with and adapt to the challenges created by the assessment of culturally diverse students. The aims of this paper are threefold: Firstly, it aims to uncover the categories teachers use to make sense of potential diversity in their classroom practice. Their perceptions and interpretations of diversity are seen as a precursor for the actions they take when confronted with student diversity in their assessment. Secondly, it analyses the assessment strategies teachers report using as they endeavour to respond to student diversity. Thirdly, we identify inhibiting and facilitating factors that contribute to teachers’ willingness and ability to innovate in assessment methods in the context of student diversity.

3 Methodology

This paper draws on 20 school case studies in which teachers and school leaders explain their assessment challenges and practices at the lower secondary level. The schools are drawn from four different European countries, Austria, Ireland, Norway and Turkey, which represent a wide variety of both teaching and assessment practices and migration experiences (ACRAS 2019). However, this paper does not aspire to make comparative claims about typical practices in these countries (for which the database would be too small). Instead, it uses four different school systems as a source for sampling greatly dissimilar contexts and experiences, and illuminating the wide variety of potential teacher responses to the conduct of assessment in diverse classrooms. Secondary schools were chosen as the focus for the study because we expected the grading and certification aspect to be relevant which would not have been the case in primary education in all participating countries.

The sampling of schools within the countries followed the logic of theoretical sampling and aimed to achieve a diversity of cases in order to mirror the heterogeneity of the research field (cf. Kelle and Kluge 2010). The schools were characterised by major variations in the percentage of migrant students. These came from different linguistic, cultural and geographical backgrounds but were integrated into the schools attending the same classes as their peers. In the Austrian and Irish case schools, the percentage of migrant students varied between 10 and 60%, in Norway between 5 and 65%, and in Turkey between 5 and 15%. In total, interview data from 115 staff from five secondary schools per country were included in the analysis (including, in each school, the head teacher, a teacher with a particular function for teaching or assessment, a teacher with a particular function for diversity or equality, a language teacher, a STEM teacher, a teacher of a migrant mother tongue and a class teacher).

Interviews were based on a semi-structured interview guide shared between the countries (see Appendix). The guide consisted of questions derived from a conceptual framework on culturally responsive assessment practices that was developed as part of the project (Brown et al. 2019). The inclusion of open-ended questions allowed practices and concepts of culturally responsive assessment not foreseen in the conceptual framework to emerge. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Interview data were coded according to the country, case study school, and the position of the interviewee (school leader or teacher). For example, when referring to the code AT_CS4_T1, the first two letters identify the country, the next two letters and numbers identify the case study school, and the final letter and number (which may be omitted when reference is to a case study in general) identifies the position and identity of the interviewee (Table 1).

The analysis followed two steps. First, data were analysed according to a case study approach (Yin 2009) concentrating on exploring patterns in each country with respect to how interviewees described aspects of diversity that the teachers attend to in assessment situations, and strategies that they apply to respond to diversity. Second, a cross-case analysis was conducted, in order to compare and contrast the emerging data from 20 schools in the four countries. For this paper, the main findings relating to the three research questions outlined above have been condensed into the central ideas and themes reported in the next section. These are illustrated by a series of statements and quotations which focus on important aspects of teachers’ reasoning and actions when they are attempting to engage with cultural diversity in assessment situations.

4 Presentation of findings

The theme of assessment in situations of diversity touches upon the fundamental ‘dilemmas of schooling’ (Berlak and Berlak 2014/1981). Are all learners to be treated equally, or is it justifiable to give different tasks and use different criteria for evaluating the performance of certain students? Is the focus in classrooms on ‘supporting or is it on monitoring and assessing the student’ (Newman 1997, p. 263)? Depending on the answers to these questions, the selection of knowledge, organisation of learning and assessment of resulting competencies will be conducted in different ways. The actions of teachers can be viewed as practical responses to such questions in the face of ‘competing and conflicting ideas in the teacher’s mind’ [and in the teachers’ environment; the authors], about the nature of childhood, learning and social justice’ (Berlak and Berlak 2014, p. 1). In our analysis, we aim to uncover categories and attitudes which teachers employ to make sense of diversity in their classrooms and consequently in their practice. Their perceptions and interpretations of diversity can be interpreted as a precursor which informs the actions they take when engaging with student diversity and in handling possible dilemmas in assessment situations.

4.1 Aspects of diversity

There are a range of dimensions of diversity which impinge on educators as they seek to appropriately respond to the needs of migrant students both in terms of pedagogy and assessment. Those that came to the fore in this research are considered below.

4.1.1 Proficiency in the language of instruction is the main dimension by which diversity in classrooms is perceived, explicitly discussed and processed

Teachers may observe and talk about all kind of differences between their students; however, with respect to their classroom practices, the student’s grasp of the language of instruction was, by far, the leading factor mentioned in our interview data. This is true in all country cases if less pronounced in Ireland, where English is the language of instruction, and it is more likely that many migrant students will have some knowledge of English, before they move to Ireland in comparison to the Norwegian, Turkish and German language in the other cases. If there are special organisational or didactical arrangements for migrant students, they will be organised, in most cases, according to student abilities in the language of instruction (see examples in Table 2).

While the focus on competences in the language of instruction is, perhaps, understandable (since this language is the prime instrument of teaching in most subjects), it may also implicitly (and maybe unconsciously) promote both a deficit perspective (‘students lack essential means of learning’) and teacher feelings of having to cope with immense challenges.

The big problem for teachers is that [the students’] language might not be up to the standard that is needed to fully participate in class. (IR_CS5_L1).

The students have problems in Turkish and mathematics classes, and this is due to their lack of language skills. (TR_CS2_T2).

Similar attitudes became apparent, in a different way in the interviews when Austrian and Norwegian teachers—with positive surprise—referred to ‘students’ good aptitude for learning the language of instruction’ (AT_CS4_T3) or described migrant students who mastered the Norwegian language well enough to follow the lessons and take part in ‘ordinary assessment’ as ‘normal students’ (NO_CS2_T2).

4.1.2 In some countries, the aspect of diversity as it relates to the language of instruction was reinforced by analogous administrative distinctions

In Austria and Norway, and to a limited extent in Ireland, language proficiency or lack of it is reinforced by administrative distinctions and labelling. In the case of Austria, when students cannot follow instruction because of a lack of competence in German (i.e. the language of instruction), they are given ‘extraordinary status’. This status allows them to participate in the classroom like regular students from day one onwards. However, they are not obliged to participate in tests, and the teacher is not obliged to grade. Students may be transferred to ordinary status after a year, but the extraordinary status may be (and very often is) extended up to 2 years because of language reasons.

Although the status ‘extraordinary’ is clearly defined by law, teachers have different interpretations, and different routines for translating legal requirements into practice have been established. The legal regulations provide for grading extraordinary students in some subjects they are good at, such as English or Maths (e.g. AT_CS4_T3), while they still may not be graded in other subjects for which the language of instruction may be more important. However, there were teachers and school leaders in the Austrian sample who (wrongly) held the view that the grading of extraordinary pupils was at all forbidden (AT_CS1_L).

This administrative distinction suggests clear categories for teachers: ‘The only distinction for me is: is the child to be tested or not?’ (AT_CS1_T7). The boundary between ‘extraordinary’ and ‘ordinary’ may induce some schools to provide a completely different type of education for extraordinary students by concentrating on language acquisition and neglecting other subjects (AT_CS5_T8).

In the case of Norway, minority language-speaking students who enter lower secondary schools in the last half of a school year are also exempted from grading if the parents agree (Education Act 1998, §3-21). Moreover, students in lower and upper secondary schools, who, according to the Education Act (1998, §2-8 or 3-12), are entitled to special education in the Norwegian language and offered an introductory course, can be exempted from grading during the period of the course. These students will only receive formative assessments, and the school owner has the responsibility to outline the consequences for the students with respect to receiving grades and being exempted from grading.

Finally, while English is the language of instruction in Ireland, Irish is also a compulsory subject. However, an exemption is granted if a student’s education up to 11 years of age was outside the country or if a newly arrived student has no understanding of English or Irish. One benefit of being exempted from Irish lessons is that those students are given additional tutoring in English during five class periods a week.

4.1.3 Although the acquisition of the language of instruction is a matter of prime interest in all countries, there are different strategies to enable this between and within countries

Arrangements for learning the language of instruction differ across countries with respect to inclusive vs exclusive arrangements (i.e. whether or not immigrant students are learning the language in special classes separate from other students) and duration (i.e. for how long special arrangements for language acquisition are applied). As Table 2 shows, the examples range from no special arrangements (Turkey) to a short language training period (Ireland) to special language instruction for a period of up to 2 years (Austria and Norway). These examples, however, are not in all cases indicative of the whole country, since there may be vast differences between arrangements in different schools within a country. Variations between countries and schools may be connected to the fact that decisions concerning the education of culturally diverse populations are often not taken based on evidence, but that schooling traditions and political considerations play an important role.

4.1.4 Few teachers have acquired competences in teaching the language of instruction as a second language

The ‘language of instruction’ is one of the main instruments of teaching. If teachers cannot use this instrument in the way they are used to, they will experience it as a challenge and—if they do not have strategies to cope with it—it can be viewed as an additional burden on their professional work. Even though proficiency in the language of instruction is perceived as the key aspect of responding to diversity, only a few teachers in the Austrian (and none in the Turkish) case studies seem to have acquired competences in teaching the ‘language of instruction as a second language’ (AT_CS4_T2).

Furthermore, teachers in Norway and Ireland did not generally talk about Norwegian or English as a second language—except for L2 teachers, of which schools reported wanting more in both countries. However, in the majority of case studies, teachers recount some strategies that they use to cope with linguistic diversity. In the case of Ireland, two of the case study schools reported that ‘students are encouraged to use their first language in the classroom’ (IR_CS2_T1), with the belief that ‘students should continue to develop their first language, as it helps them to develop concepts in English and to acquire the English language’ (IR_CS5_L3). Norwegian teachers also pointed to a lack of conceptual understanding as equally challenging.

Lacking language competency is a challenge. The students have much more knowledge than they can express with words (NO_CS4_T5)

There is a challenge with subject-related concepts which has consequences for students’ motivation. If you do not know the concepts, the learning is characterised by being very basic. It is difficult language-wise to reflect, to understand, to compare, to draw parallels. This does not only concern minority language students, but all students who struggle because they lack words and concepts (NO_CS3_T2)

4.1.5 ‘Cultural diversity’ is not often explicitly mentioned in the teachers’ and schools’ efforts to respond to diversity. This seems to relate to the perceived sensitivity and vagueness of the concept

Although classroom diversity is often associated with ‘cultural diversity’ in the public debate, there were very few examples in our data, except for some rare exceptions, in which interviewees explicitly referred to cultural differences when speaking about assessment, teaching and school.

It is interesting, for example, that some pupils, I think it was a Hungarian, do have a different way to do specific calculations, e.g., multiplication is different there, ah, I use that in teaching and tell the other children, make them aware that there are other ways, too. (AT_CS5_T1)

In science, for instance, we have Greek numbers and some words with a Greek origin. So, students coming from Greece recognise some of this. However, as I said, we don’t use it to a large extent. (NO_CS1_T2)

These statements are an indication of intercultural awareness. The first teacher did not refer to an alternative practice of multiplying as a ‘wrong way’, but as a different, even interesting mode, i.e. in a non-judgemental way. Additionally, he used this instance of diversity in his teaching, to raise students’ awareness of the fact that there are different, but equally valid, ways of multiplying (Kaiser et al. 2006; Blömeke 2006, p. 394). This approach of acknowledging differences and doing this in front of the class appeared to strengthen the position of the children with migration backgrounds among their peers. Although this specific instance did not refer to assessment practices, one can imagine that this teacher would not insist on the ‘normal’ way of multiplying when assessing the student; i.e. he possibly would not measure students against culture-specific images of the subject to be learned and of ‘studentness’ (how students behave) in grading situations. In another example, a social science teacher expressed awareness of students whose cultural experiences were out of harmony with curricular content, and empathy that this may make it very challenging for these students to understand some concepts.

So, you have an idea, about democracy and participation for instance, where one of my students, coming from […], had very different ideas about IS and torture for instance, and, sort of, his concepts compared to other students, were very different. And you notice in assessment situations too, that you do not, that you do not manage to see what underlies student responses. You simply think that [the student’s] opinions are rigid, without seeking insights in the cultural background and why the student reacts as he does. (NO_CS3_T3)

All in all, there were comparatively few references to ‘cultural’ differences (other than language differences) in our case studies. What are the possible explanations for this finding? Firstly, cultural differences are sensitive. ‘Language’ offers a more clear-cut distinction, although it often functions as a signifier for a broader ‘otherness’ which may be associated with ‘culture’ and ‘ethnicity’.

Secondly, there is also diversity within the group of migrant students that is challenging to grasp and describe. For example in Ireland ‘newcomers’ are generally very diverse, drawn from heterogeneous ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds, including some migrants who ‘are already proficient in English and whose parents have high educational aspirations’ (IR_CS2_L1). The label ‘not speaking the language of instruction’ is easier to handle and less prone to misconception. As stated by a Norwegian interviewee,

No, my impression is that they did an exceptionally good job in a primary school in integrating those [students] who have arrived during primary school. So, my impression is that the students are similar in the way they think and behave. (NO_CS4_T2)

Thirdly, many teachers do not have enough intercultural competence to feel well-equipped to address ‘cultural differences’ in interviews (and maybe also in classroom work). As such, the development of intercultural competence in the teaching force seems to be an issue in all countries.

4.2 Assessment strategies for responding to diversity

Concerning the second research aim, we were interested in the ways in which teachers relate to situations of diversity and react to the differences they perceive. While we saw few examples of well-developed and coherent practices of culturally responsive assessment at school level, many teachers across the country cases do take account of those diversities they perceive and use a whole range of strategies by which they aim to help students to demonstrate their competencies.

4.2.1 In order to relate to student diversity in conducting classroom-based assessment, many teachers adapt their assessment procedures and/or their grading

In our case studies, we witnessed a variety of methods that teachers and schools use to cope with student diversity. However, there was no single dominant strategy. Often, these practices were based on either the teachers’ perceptions of the students’ individual needs and/or drawn from the teacher’s classroom experience. These strategies were either ad hoc solutions to the problem of limited proficiency in the language of instruction, or they were long-term strategies of individualisation and differentiation which aimed to increase student responsiveness in general and were not limited to the cultural origin or assumed otherness.

Many of these strategies in each country can be subsumed as versions of formative assessment, such as ‘self-assessment’ or ‘group performance’, together with other types of performance, from pictorial to oral and written, hearing, reading and other formats. Generally, teachers who were competently working informed by a formative assessment philosophy seemed better equipped for culturally responsive assessment (Nortvedt et al. 2020). In teaching second language learners, the concept of ‘scaffolding‘ (Ovando et al. 2003, p. 345) has spread to a number of classrooms. This offers contextual supports for understanding through the use of simplified language, teacher modelling, visuals and graphics, cooperative learning and hands-on learning; similar strategies in assessment may be interpreted as a natural corollary. As such, the strategies reflect teachers’ inventiveness and sensibility; however, they were often intensely individualised and not shared. Additionally, the described instances of flexibility, creativity and reflexivity of some teachers and their students can be seen as components and expressions of intercultural competence even when ‘culture’ was not the issue that was explicitly mentioned.

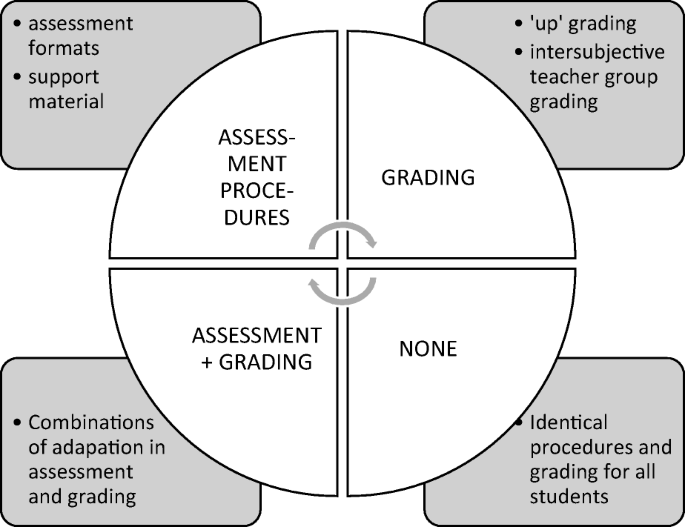

Looking more closely at the teachers’ strategies, it is possible to distinguish two elements within assessment (Eder et al. 2009): ‘procedures of assessment’ which refer to the processes of devising performance situations (such as assignments or tests), assigning them to students and monitoring students’ performance in these situations, and ‘grading’ which refers to the process of attaching evaluative judgements (such as marks, grades or other evaluative descriptions of the performance shown) to the students’ performance. In our data, there were (a) teachers who adapted their procedures of assessment to the needs of the students, (b) others adapted their grading, (c) some adapted both and (d) another group adapted neither assessment procedures nor grading (see Fig. 1).

Adapting procedures of assessment

When attempting to meet the needs of migrant students, many teachers in our case schools adapted their assessments by modifying the procedures of assessment in the following ways:

-

Extra time

One of the most frequent strategies is time adaptation. Students whose first language is not the language of instruction may use more time for the same questions (e.g. AT_CS1). This is in line with legal regulations in Austria and Norway.

-

Changing assessment formats

Especially when students were literate in another script and still had difficulties in writing in Latin script, or just had difficulties writing in the language of instruction, teachers changed from a written to an oral format. Teachers in many instances also offered students the possibility of replacing a written or oral assessment by a presentation which they could prepare at home (e.g. AT_CS2_T3).

-

Changing the test language

When some teachers realised that certain students were more proficient in another language than the language of instruction, students were allowed to complete the test in the other language—provided teachers were themselves proficient in this language or a person was able to translate the test.

We also have students who then change the language to do their Physics test in English, and that is perfectly ok. This is offered by the English teacher, she says, ok, he can speak English much better than German, but with English, he would do it, then we’ll do it in English. (AT_CS1_T3)

-

Offering additional support

For example, teachers offer a list of keywords in the language of instruction with mother tongue explanations and/or ask other students for mother tongue support (AT_CS1).

I make it possible for them to teach to their friends the meaning of the words they learn in their own language. (TR_CS4_T2)

Many of these activities were ‘not only useful for migrant but for all students’ (IR_CS4_T4), e.g. discussion of ‘keywords before reading the main text’ (IR_CS4_T4) which, in some instances, included different contexts of the word together with an image of the word.

As is the case with state examinations in Ireland, students of a certain language proficiency level were able to use dictionaries during the test ‘to understand what they are being tested on if they don’t understand the meaning of a word. (IR_CS5_L1)

In an iPad-enabled classroom a teacher used electronic translation devices (Google translator) to communicate with a newcomer initially. Norwegian examples show how new teaching material can be used for supporting migrant students.

He often comes to me with something written in Italian, which he has translated for me using Google. I often think; Yes, funny. Yes, but that’s how we communicate, and he feels I understand him, I know if he has a problem …. (AT_CS4_T3)

So, there are some subjects (…) like grade 8th science that has ‘Eureka’ - a smart-book that can read aloud. They can listen while they read. I think that this is a good resource for minority students and students with language disabilities. (NO_CS1_T1)

-

Peer assessment

Peer assessment occurred primarily during presentations and group work when students were asked to give feedback. In some instances, students even defined the criteria used for evaluation. In other situations, teachers organised panels with observer roles including brief written reflections:

We often use peer-assessment in groups or with an assessment partner where the students compare their responses and provide feedback to each other on written tasks. We do not use so much self-assessment yet, this we will do later on. Until now, we have focused on developing a “tool box” where they get to see examples of different tests, written assignments, feedback and so on, but we have not let them participate actively yet. (NO_CS1_T1)

So, we have now ... we started with discussion rounds on various topics, and there we always have observer roles to watch the whole thing and then give feedback afterwards. (AT_CS2_T7)

Adapting grading

Another strategy is to adapt the grading to the student’s competence level.

-

‘Language up-grading’

Some teachers retain the regular procedures of assessment (such as tests, homework and other activities) without any particular adaptation to the special needs of migrant students or any differentiation in general. However, they take the students’ language proficiency into account when they decide on the grade, which is recorded in the report card (e.g. AT_CS4_T1). This is in line with the legal situation in some countries (e.g. in Austria: teachers may take the linguistic situation of the students into account when deciding on the grade), while it is not allowed in other countries, e.g. in Norway where teachers are instead obliged to adapt the assessment.

Teachers who use ‘language up-grading’ explain it as accounting for the fact that written tasks require much more effort from students raised in another language and, even more so, in a different writing system (AT_CS3_T4) similar to Deseniss (2015).

In more professional terms, ‘language up-grading’ requires teachers to deviate from the social reference norm (considered ‘just’ in traditional schools) and use individual reference norms, i.e. to grade according to individual progress instead of social comparability. ‘Language up-grading’ also requires to distinguish between content and language performance in assessing competencies.

… the [recently immigrated] girl has collected many points because she understood the logic of the assignment, she has numeracy skills, it is only the language competence which is missing: I can be responsive to that, see, she is not able to cope with assignments with a longer written text in the beginning. However, all the other capabilities may be appreciated. (AT_CS1_T3)

No adaption of assessment

In some classrooms, we found no adaptation to the diversity of students at all. Due to the legal requirement in Norway regarding educational adaption to individual needs (Education Act 1998, § 1-3), teachers are obliged to adapt both their teaching and assessment to individual students. However, there are still individualised practises, and the degree of adaption might, therefore, differ between teachers. In the Turkish cases, teachers in their classroom-based assessment usually ‘use the same tests for all students’ (TR_C4). When we encountered non-adaption in other countries (Austria, Ireland and Turkey), there were different explanations: Some teachers expressed compassion for the situation of newcomer students. They felt that non-adaptation of assessment is unfair to these students and, at the same time, thought that they were forced into non-adaptation by their national assessment system.

The assessment system [used in the school] is not fair in this respect, if they have such a deficit and therefore cannot show the performance expected. However, we cannot help it now, can we? (AT_CS4_T6)

Written papers in state examinations should be screened for appropriate language, as they do not reflect the diversity of language we now have in our secondary schools. … Setters of examination papers should be trained in language matters. (IR_CS3_T2)

Other teachers identified strongly with (what they perceived as) the legal rules or concepts of formal equality and did not consider any alternative:

We cannot do otherwise. It will be difficult ... to judge everyone equally … without going down with the standards. (AT_CS2_T3)

It is very difficult, you know, and would be difficult to have some rules [for] some and some rules for others. (IR_CS5_T3)

A small group in some countries did not seem to care about the problem.

I think nothing should be ‘adjusted’, so just because they are different cultures. Everyone has to be judged the same. (AT_CS1_T1)

It depends on the student. There is not a problem if the student is willing. (TR_CS2_T2)

The wide variation in strategies and in personal interpretations of the legal situation seems to indicate that there is ample leeway for professional development programmes offering teachers support and guidance in a work situation they were not trained for.

4.3 Supportive conditions for responding to diversity

The third aim of this paper is to investigate where teachers can turn to if they need support in responding to student diversity in their assessment work. From the perspective of the teachers, there seems to be little support available. However, the existing assessment practices or regimes represent a resource for teachers.

4.3.1 Different countries are characterised by different assessment regimes: they are a resource for teachers’ responding to diversity in assessment; they open up potential strategies of adaptation.

Countries differ in their legal requirements for assessment, which are transmitted through teacher education and enacted through individual and collegial practices of assessment and grading in schools. These ‘assessment regimes’ form a resource for schools’ and teachers’ individual and collective action, and thereby shape strategies of adaptation.

Assessment in Austrian (‘segregated’Footnote 1) lower secondary schools is purely teacher-based; certificates originating from it are important for access to a differentiated ‘segregated’ upper secondary education system. This special assessment regime seems to limit the options teachers have in coping with diversity. In such a selective system, there is much attention paid to the comparative fairness of assessment, which makes it more difficult to be responsive to the special needs of students than it might be in more inclusive systems (cf. Popham 2009). This may have also made it more difficult for formative assessment or assessment for learning to flourish. Even a strategy like ‘language up-grading’ may be understood as a way of achieving ‘comparative fairness’, which would not be possible (or indeed necessary) in a system like Norway’s, which has its traditional focus on supporting individual progress in lower secondary level.

In Ireland, in contrast, assessment at the end of ‘non-segregated’ secondary junior education (referred to as the ‘Junior Cycle’) is based on teacher assessments and externally devised examinations which open up access to a ‘non-segregated’ upper cycle. The upper cycle ends with external state examinations, which are relevant for tertiary access. The external tests tend to focus the attention of teachers and students; however, the teacher’s role is conceived as supporting students’ learning for assessment (instead of ultimately judging students’ results which does not apply in Ireland). In the junior years, there is more freedom to adapt to students’ needs, but the upper secondary leaving certificate is such an important milestone in educational careers that there is a ‘washback effect’; the closer the final examination, the less freedom is experienced by teachers concerning assessment, and the more teachers tend to focus entirely on results. As all students are preparing for the ‘Leaving Certificate’, this has an impact right through secondary schooling (Burns et al. 2017). As stated by one interviewee:

I think that the introduction of CBAS (Course Based Assessments) is a very good move for the introduction of Assessment for Learning and for migrant students. But to be honest, the main focus is still the Leaving Cert so a lot of what we hear about is nice and what might be worthwhile assessment strategies goes out of the window when students do the Leaving Cert. The real is what they get in the Leaving Cert. How this fears out for students who have just entered the country, not so well I imagine. (IR_CS2_T3)

In Norway, as with Ireland, assessment at the end of ‘non-segregated’ lower secondary education is also based on teacher assessments and externally devised examinations. Although all students have a guaranteed place in upper secondary education, their results in the lower secondary level will enable them to opt for an academic or a vocational stream of the ‘segregated’ upper secondary cycle. The policy of guaranteed places in upper secondary education, the legal right of students to adapted education according to their individual needs as well as a legal policy for formative assessment in the form of assessment for learning seems to leave more freedom for teachers to apply culturally responsive practices in their assessment.

In Turkey, there is a central state examination at the end of 8th grade. All children, including foreign nationals, have the right to access ‘basic education’ services delivered by public schools. If international students are enrolled in a public school, the Local Education Authorities (LEAs) are responsible for assessing the student’s educational background and determining which education level the child will be enrolled in (Access to Education in Turkey 2019). In addition, in-service training for inclusive education is provided for teachers who have Syrian students in their classrooms (Promoting Integration of Syrian Children into the Turkish Education System 2019). All these initiatives may be considered as the beginning of culturally responsive practices in the assessment of immigrant students.

4.3.2 Established practices of formative assessment in a country can help individual teachers in adapting to diversity in their assessment

Whether or not practices of formative assessment are stipulated by educational legislation and supported by professional development, teaching material and other support offers may be a particularly relevant aspect of an assessment regime. Norway is a good example of established practices of formative assessment, due to a long-standing policy for adaption to individual student needs since 1975. There are certainly differences between individual teachers, schools and local communities; however, according to national policies, requirements that all schools should implement Assessment for Learning and formative assessment have an even longer tradition. In Ireland, formative assessment was not used as frequently in the past; ‘ten years ago, assessment for learning was never really mentioned at all’ (IR_CS5_L1). It is only in the last few years that formative assessment has attracted more attention with its introduction to the discourse of assessment at primary level (NCCA 2008), with its promotion as part of Junior Cycle reform and through influential stakeholder groups in the system, such as the inspectorate. In these cases, it is easier for individual teachers to practice formative assessment than in Austrian and Turkish schools, where formative assessment has a weak tradition connected with the prevalence of teacher-based assessment for certification.

4.3.3 An established discourse in the profession on both diversity and assessment helps individual teachers adapt to diversity in their assessment

Teachers’ work is not well understood if one looks only at the individual level. It takes place in a ‘community of practice’ (Lave and Wenger 1991), which may be more or less well developed. These communities of practice offer a ‘background web’ of understandings, interpretations, strategies and instruments which individual teachers can draw on in their daily work and in their attempts to cope with new situations. If there is an established professional discourse on diversity and/or on assessment, then it is supportive of teachers finding solutions for creating diversity in assessment. Although the awareness of diversity in classrooms is rising in Austria and Turkey, there is not really a discourse on this issue that involves much of the profession. In Ireland, the professional discourse on evaluation has increased as a result of new inspection practices and may stimulate awareness concerning diversity and assessment (IR_CS5).

4.3.4 A school policy on diversity and/or on assessment and formal and informal practices of teacher collaboration can help individual teachers adapt to diversity in their assessment

In some of the Norwegian schools, there are school policies in place which staff have agreed upon. School leaders give teachers resources accordingly; in these schools, it is easier to use formative practices. In case school 5, for example, a specific school policy of adaptive assessment has been implemented, which has teachers assessing tests together with the students (NO_CS5). This practice is supported by the Education Act (1998), which gives students a general right to participate in their own assessments.

Three of the Irish case schools have policies on multiculturalism and respect for everyone, and these policies seem to shape the learning environment in these schools (e.g. IR_CS5). Turkish case schools may or may not have some collaboration concerning assessment; however, they do not have any consistent school policy concerning assessment or migrant students or diverse classrooms (TR_CS4).

During the last decade, Austrian education policy has promoted increased attention to the individual needs of students, and differentiation and individualisation of teaching (Altrichter et al. 2009). Nevertheless, there is a wide variation of practices of assessment and grading. Only a few schools have consistent assessment policies, and in those that do exist, the aspect of linguistically or culturally responsive assessment is not covered (e.g. AT_CS1_T2). The obligatory development plans (which schools have to negotiate with their regional administrators as a part of ‘contract management’; see Altrichter 2017) may include elements which are helpful for culturally responsive assessment. Thus, in case school 5, an active and quite interventive system of diagnosis and support has been established, which is useful for responding to student diversity (AT_CS5).

5 Discussion and conclusion

This paper provided an exploratory analysis of the perceptions and strategies that teachers use to assess students in diverse classrooms. Interview and documentary data from 20 schools, and 115 teachers and school leaders in four European countries—Austria, Ireland, Norway and Turkey (five schools per country)—were used to study some features of the challenges teachers face when assessing students from diverse cultural backgrounds. While the situation in these countries, and even between schools in these countries, varied in many respects, it seems possible to come up with some insights to the problem of culturally responsive assessment that may be relevant—if to varying degrees—for many European countries and classrooms.

A key finding is that ‘proficiency in the language of instruction’ is the main dimension by which diversity in classrooms is perceived, explicitly discussed and processed by teachers. Contrary to the public debates in many countries, there is much less reference to ‘cultural differences’ in our case studies, probably because ‘culture’ is a much more difficult concept to handle in classroom work. However, the massive emphasis placed on ‘proficiency in the language of instruction’ is worth interrogating further.

Historically, schools have been a major instrument of supporting the idea that nations are monolingual by promoting a ‘standard language ideology, which elevates a particular variety of a named language spoken by the dominant social group to a (H)igh status while diminishing other varieties to a (L)ow status.’ (Ricento 2013, p. 531). While the acceptance of language variety in European schools seemed to have increased in the wake of sociolinguistic research and globalisation, the contemporary waves of migration seem to be countered by a re-emergence of the ideology of monolingualism which ‘sees language diversity as largely a consequence of immigration. In other words, language diversity is viewed as imported.’ (Wiley and Lukes 1996, p. 519).

The insistence on proficiency in the language of instruction is a variety of the concept “language-as-resource” (Ruiz 1984) which many teachers often implicitly and benevolently seem to subscribe to, because they want to open up participation opportunities for their students. On the other hand, there is more in languages than ‘their utilitarian benefit’ (Ricento 2013, p. 533). Those whose language is tacitly considered secondary or openly devalued, will experience their identity, status and place in life challenged (Baker 2006; Blommaert 2006). ‘Language first’ policiesFootnote 2 insisting that migrant students have to learn the language of instruction before they can participate in mainstream classes with all other students seem to reinforce monolingual attitudes in the teaching force.

‘Language proficiency’ also seems to shift the responsibility for demonstrating learning to the student and, thus, implicitly alleviates challenges for teachers which many of them experience as difficult and demanding. Additionally, it seemed that only a few teachers in our cases had been explicitly trained for teaching the language of instruction as a second language or for coping with cultural diversity in teaching, and even more so in assessment.

Secondly, while some teachers did not feel that assessment should take account of student diversity, most teachers tried to adapt their assessment procedures and grading to help students from diverse backgrounds to show their competencies and to experience success. Rarely were these responses organised and supported by school policies, institutionalised in-school teacher collaboration or regional/national policies focusing on culturally responsive assessment. More often, teachers used their educational repertoire or developed ad hoc solutions to do justice to individual students’ needs and potential.

Yet, national policies for individualisation and differentiation and in a small number of cases in-school policies on assessment and/or cultural diversity did give some limited support to individual teachers in their attempts to cope with a situation experienced as challenging by many. Overall, in most interviews, teachers did not feel well-prepared for a diverse education system either from their pre-service teacher education or from the policies and supports provided by schools or education authorities.

What are the potential consequences and recommendations to enhance culturally responsive assessment that can be drawn from this situation?

5.1 Clarifying the concept of ‘responsiveness to cultural diversity’ in the professional discourse in education

The case studies indicated that the term ‘cultural diversity’ is often avoided in explicit in-school discourse and only used implicitly to point to ‘increased difficulties’ for the teaching profession. Responding to cultural diversity is indeed a difficult concept, and it is undoubtedly in need of further clarification, in particular as it applies to classroom practice. In our view, the OECD’s (2016; Burns et al. 2017) work on global competence provides a formulation of culture which neither reifies ‘cultures’ as a given, nor loses itself in an incomprehensible array of customs, attitudes, artefacts, and so on. What is described is a concept of culture which does not limit students to narrow, pre-conceived perceptions but allows for the development of both the students and the culture. However, it is important to communicate such an understanding to the teaching force and the public, and to equip teachers and schools with feasible strategies for translating such an understanding into practice.

5.2 Teaching material and teaching resources are helpful for teachers, as they show teachers appropriate ways of positively engaging with cultural diversity

In many case schools, teachers reported a lack of adequate support material. On the other hand, we found other teachers pointing to appropriate and relevant resources which were publicly available but were rarely used. There is some indication that this discrepancy between support material available and used may be connected with a lack of sensitivity to the problem in general and lack of expertise with respect to intercultural and multilingual education and culturally responsive assessment. At times, this lack of expertise may also be connected with a lack of leadership, ignorance or xenophobic attitudes. Teachers with knowledge in this field seem to find adequate resources in most countries and schools and to support their colleagues in this respect. Accessible resource persons with specialised knowledge could ultimately help to enhance the schools’ expertise in this regard.

Internet- and ICT-based media may be more readily accessible to teachers who know about their existence and know how to use it. Another advantage is their potential flexibility which allows different types of use even in initially unforeseen situations (e.g. the Norwegian language support app CD-ORD is used as a translation device; NO_CS4_T2).

5.3 Professional development for intercultural competence and culturally responsive assessment is an issue in all countries

The case studies indicated that many teachers and schools have difficulties in constructively engaging with the challenges of the cultural diversity of students, and also the results of international tests strongly point in that direction (Herzog-Punzenberger, 2019). Nevertheless, it is not only teachers who require professional knowledge of culturally responsive education. According to an EC-commissioned study on diversity in initial teacher education, there are few initiatives in Europe to train teacher educators in linguistic and cultural diversity including responsive assessment strategies (Dumcius et al. 2017, pp. 6870). As long as teacher educators are not well-equipped for preparing teachers to do this work, it is doubtful that adapted curricula and resource material will directly impact classroom practice. Therefore, the leadership of teacher training institutions concerning linguistic and cultural diversity is one of the most important steps towards improving culturally responsive assessment.

While there are several options for professional development concerning multicultural education and second language learning available in Austria, Ireland and Norway, their impact on the work in schools and classrooms was not entirely convincing in these case studies. New in-service formats (e.g. coaching and long-term development processes of both school policy and classroom practice; Timperley et al. 2007; Lipowsky and Rzejak 2014) are needed. Indeed, some schools were not aware of both the availability of professional development on culturally responsive practices and the need for such competences (e.g. AT_CS4_T2).

It may well be that both are necessary: relevant and accessible teaching material and professional development made readily accessible on the one hand, and a system-wide strategy which makes school leaders and teachers aware that these resources are available and that building up such competencies is part of each school’s professional responsibility, on the other.

5.4 As responsive forms of assessment are new in many cases and may vary between classrooms, students’ and parents’ understanding is essential

Significant classroom diversity usually entails that the school’s parents vary widely with respect to their expectations, aspirations, competencies and prior school experiences. While immigrant parents were in some cases characterised by low education levels and low income with vague educational aspirations (TR_CS5), there were other cases in which immigrant parents and students held high expectations and actively pursued them (AT_CS5).

For example, teachers in one school observed that some of the well-motivated parents with a migrant background were very focused on their children performing well in the state examinations and were not interested in any assessment other than tasks that prepared them for the state exams. As stated by one teacher, ‘these students just say …, just give me the notes so I can learn them off for the exam’ (IR_CS2_T2).

In any case, diversity of parent expectations may increase in a way that is not always clearly visible. As ‘justice in assessment’ and the success of students (giving the right of entry to further education and employment) are prime criteria by which parents evaluate a school’s work, it will be necessary that schools proactively work with parents if they want to introduce new forms of assessment. In Norway, primary and lower secondary education teachers are legally required to hold ‘learning development dialogues’ (similarly ‘parent-student-teacher conversations’ in Austria) with students about performance, progress and potential improvement actions at least twice a year, for which they prepare a written report on the students’ learning progress. As migrant parents may have problems in understanding the report or the overall procedure, some schools provide courses for parents on how to participate in these meetings.

In conclusion, it is acknowledged that the findings and recommendations of this study are limited by the number of cases and its exploratory nature. Sampling of countries and schools was mainly based on opportunity and did not aspire to give a full picture of the culturally responsive assessment practices in these countries. Nevertheless, we claim that we have collected insights into the thinking and practices of schools and teachers trying to engage with cultural diversity in their classrooms and how this diversity shapes, to varying and often limited extents, the teaching and assessment methodologies employed. The response in many schools and classrooms to increased diversity is still short of anything that approaches culturally responsive pedagogy and assessment, a finding which supports the outcomes of larger quantitative studies on cultural and linguistic diversity in the teaching profession and in schools (OECD 2019). Nonetheless, this study also, and most importantly, indicates that many schools and teachers are well disposed, on the whole, to embracing diversity and adapting assessment to being more culturally responsive. It is not a lack of goodwill but more the limitations and constraints of existing assessment policies, together with inadequate training and limited supports which are inhibiting a great leap forward in this most urgent area.

Change history

19 August 2020

The original version of this article unfortunately contained a mistake.

Notes

The term ‘segregated’ points to a system in which parallel educational options for the same age group are in a hierarchy with respect to further educational options (e.g. access to tertiary education).

For example, in 2018/19, the Austrian government introduced separate classes for immigrant students in which they have to learn the language of instruction for one to four semesters. Students can only be mainstreamed if they pass a special language test which is administered at the end of every semester (BMBWF 2020).

References

Access to Education in Turkey (2019). Accessed 1 Dec 2019, from https://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/turkey/access-education-1

Aceves, T. C., & Orosco, M. J. (2014). Culturally responsive teaching (Document No. IC-2). Accessed 20 Oct 2019 from http://ceedar.education.ufl.edu/tools/innovation-configurations/

ACRAS. (2019). Characteristics of school systems and student assessment in Austria, Ireland, Norway, and Turkey. Retrieved November, 19th, 2019, from https://www.acras.eu

Alcott, B. (2017). Might progress assessments hinder equitable progress? Evidence from England. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 29(3), 269–296.

Altrichter, H., Trautmann, M., Wischer, B., Sommerauer, S., & Doppler, B. (2009). Unterrichten in heterogenen Gruppen: Das Qualitätspotenzial von Individualisierung, Differenzierung und Klassenschülerzahl. In W. Specht (Ed.), Nationaler Bildungsbericht. Österreich 2009: Band 2 (pp. 341–360). Leykam: Graz.

Altrichter, H. (2017). The Short Flourishing of an Inspection System. In J. Baxter (Ed.), School Inspectors: Policy Implementers, Policy Shapers in National Policy Contexts (pp. 206–230). Cham: Springer.

American Evaluation Association (AEA) (2011). Statement on cultural competence on evaluation. Accessed 19 March 2019, from http://www.eval.org/p/cm/ld/fid=92

Arbuthnot, K. (2017). Global perspectives on educational testing: examining fairness, high-stakes and policy reform. Bingley: Emerald.

Baker, C. (2006). Psycho-sociological analysis in language policy. In T. Ricento (Ed.), An introduction to language policy. Theory and method (pp. 210–228). London: Blackwell.

Baker, E. L., O’Neil Jr., H. F., & Linn, R. L. (1993). Policy and validity prospects for performance-based assessment. American Psychologist, 48(12), 1210–1218.

Banks, J. B., & Banks, C. A. M. (Eds.). (2004). Handbook of research on multicultural education (2nd ed.). NewYork: Macmillan.

Berlak, A. & Berlak, H. (2014; originally 1981). Dilemmas of schooling: teaching and social change. London & New York: Routledge.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2012). Assessment for learning in the classroom. In J. Gardner (Ed.), Assessment and learning (2nd ed., pp. 11–32). London: Sage.

Blömeke, S. (2006). Struktur der Lehrerausbildung im internationalen Vergleich. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 52(3), 393–416.

Blommaert, J. (2006). Language policy and national identity. In T. Ricento (Ed.), An introduction to language policy: theory and method (pp. 238–254). Malden: Blackwell.

BMB [Bundesministerium für Bildung]. (2016). Lehrplanbestimmungen für Deutsch als Zweitsprache (DaZ): Fachlehrpläne für den muttersprachlichen Unterricht. Unterrichtsprinzip “Interkulturelles Lernen”. Vienna: BMB.

BMBWF [Bundesministerium für Bildung, Wissenschaft und Forschung] (2020). Deutschförderklassen und Deutschförderkurse. Accessed 17 May 2020, from https://www.bmbwf.gv.at/Themen/schule/schulpraxis/ba/sprabi/dfk.html

Bolton, G. (2010). Reflective practice: writing and professional development. London: Sage.

Brook Chapman de Sousa, E. (2017). Promoting the contributions of multilingual preschoolers. Linguistics and Education, 39, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2017.04.001.

Brown, M. (2007). Educating all students: Creating culturally responsive teachers, classrooms, and schools. Intervention in school and clinic, 43(1), 57–62.

Brown-Jeffy, S., & Cooper, J. E. (2011). Toward a conceptual framework of culturally relevant pedagogy: an overview of the conceptual and theoretical literature. Teacher Education Quarterly, 38(1), 65–84.

Brown, M., Altrichter, H., Nayir, F., Nortvedt, G., Burns, D., Fellner, M., Gloppen, S. K., Helm, C., McNamara, G., O'Hara, J., Herzog-Punzenberger, B., Skedsmo, G., & Wiese, E. F. (2019). Classroom Assessment that Recognises Cultural Difference - A European Perspective. Dublin: EQI. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.14346.52164/2.

Burns, D., Brown, M., Altrichter, H., Nortvedt, G., McNamara, G., O’Hara, J., & Nayir, F. (2017). Aiding Culturally Responsive Assessment in Schools (ACRAS) - Summary: Conceptual Framework. Retrieved October, 20, 2019, from http://www.acras.eu/3-framework

Castagno, A. E., & Brayboy, B. M. J. (2008). Culturally responsive schooling for indigenous youth: a review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 78(4), 941–993.

Crichton, J. (1998). Book review: engines of educational change: examination systems in small states. In M. Bray & L. Steward (Eds.). Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 6(2), 305–307.

Crul, M., Schneider, J., & Lelie, F. (2012) (eds.). The European second generation compared. Does the integration context matter? Accessed 9 Feb 2020 from http://www.tiesproject.eu/component/option,com_docman/task,cat_view/gid,44/Itemid,142/.

Deseniss, A. (2015). Schulmathematik im Kontext von Migration: Mathematikbezogene Vorstellungen und Umgangsweisen mit Aufgaben unter sprachlich-kultureller Perspektive. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Dumcius, R., van Driel, B., Herzog-Punzenberger, B., Kerzil, J., Wood, E., Siarova, H. Sternadel, D., Tsutskiridze, L., & Buinauskas, D. (2017). Preparing teachers for diversity. The role of initial teacher education. Accessed 9 Feb 2020, from http://www.readyproject.eu/uploads/files/1502579119PreparingTeachersforDiversity.pdf

Eder, F., Neuweg, G. H., & Thonhauser, J. (2009). Leistungsfeststellung und Leistungsbeurteilung. In W. Specht (Ed.), Nationaler Bildungsbericht. Österreich 2009. Band 2 (pp. 247–267). Leykam: Graz.

Education Act. (1998). Education Act, 20. Oslo: Government of Norway.

Espinosa, L. M. (2005). Curriculum and assessment considerations for young children from culturally, linguistically, and economically diverse backgrounds. Psychology in the Schools, 42(8), 837–853.

Eurostat (2017). Migration and migrant population statistics. Accessed 20 Oct 2019, from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=File:Non-national_population_by_group_of_citizenship,_1_January_2017_.png

Feldman, A., Altrichter, H., Posch, P., & Somekh, B. (2018). Teachers investigate their work (3rd ed.). London & New York: Routledge.

Fend, H. (2009). Neue Theorie der Schule. VS: Wiesbaden.

Ford, D. Y., & Kea, C. D. (2009). Creating culturally responsive instruction: for students’ sake and teachers’ sake. Focus on Exceptional Children, 41, 1–18.

Gay, G. (2010). Culturally responsive teaching: theory, research, and practice (2nd ed.). New York: Teachers College Press.

Gutiérrez, R. (2002). Beyond essentialism: the complexity of language in teaching mathematics to Latina/o students. American Educational Research Journal, 39(4), 1047–1088.

Hattie, J. A. C. (2009). Visible learning: a synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. New York: Routledge.

Herzog-Punzenberger, B. (2019). Mehrsprachige Schüler_innen im deutschsprachigen Raum – Kontextbedingungen und Lernerfolge. In A. Ender, U. Greiner, & M. Strasser (Eds.), Deutsch im mehrsprachigen Umfeld (pp. 58–83). Hannover: Klett Kallmeyer.

Hood, S. (1998a). Introduction and overview: assessment in the context of culture and pedagogy: a collaborative effort, a meaningful goal. The Journal of Negro Education, 67(3), 184–186.

Hood, S. (1998b). Culturally-responsive performance-based assessment: conceptual and psychometric considerations. The Journal of Negro Education, 67(3), 187–196.

Hood, S., Hopson, R. & Frierson, H. (2015). Introduction: this is where we continue to stand. In S. Hood, R. Hopson & H. Frierson (Eds.), Continuing the Journey to Reposition Culture and Cultural Context in Evaluation Theory and Practice. (pp. ix-xviii). Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

Isaacs, T. (2010). Educational assessment in England. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 17(3), 315–334.

Kaiser, G., Hino, K., & Knipping, C. (2006). Proposal for a framework to analyse mathematics education in Eastern and Western traditions. In F. Leung, K. Graf, & F. Lopez-Real (Eds.), Mathematics education in different cultural traditions (pp. 319–351). New York: Springer.

Kelle, U., & Kluge, S. (2010). Vom Einzelfall zum Typus. Opladen: Lesek+ Budrich.

Kim, K. H., & Zabelina, D. (2015). Cultural bias in assessment: can creativity assessment help? International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 6(2), 129–147.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995a). But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory Into Practice, 34(3), 159–165.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995b). Toward a theory of culturally relevant teaching. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

LeMétais, J. (2003). International developments in upper secondary education: context, provision and issues. In National Foundation for Educational Research. Dublin: National Council for Curriculum and Assessment.

Lesaux, N. K., Kieffer, M. J., Kelley, J. G., & Harris, J. R. (2014). Effects of academic vocabulary instruction for linguistically diverse adolescents: evidence from a randomised field trial. American Educational Research Journal, 51(6), 1159–1194.

Lidz, C., & Gindis, B. (2003). Dynamic assessment of the evolving cognitive functions in children. In A. Kozulin, B. Gindis, V. Ageyev, & S. Miller (Eds.), Vygotsky’s educational theory in cultural context (pp. 293–357). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lipowsky, F., & Rzejak, D. (2014). Lehrerfortbildungen lernwirksam gestalten. Lernende Schule, 17(68), 9–12.

Mitakidou, S., Tressou, E., & Karagianni, P. (2015). Implementing culturally sensitive assessment tools for the inclusion of Roma children in mainstream schools. In S. Hood, R. Hopson, H. Frierson, & K. Obeidat (Eds.), Continuing the journey to reposition culture and cultural context in evaluation theory and practice (pp. 233–250). Charlotte: Information Age.

Nayir, F., Brown, M., Burns, D., Joe, O. H., McNamara, G., Nortvedt, G., & Wiese, E. F. (2019). Assessment with and for Migration Background Students-Cases from Europe. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 19(79), 39–68.

NCCA (National Council for Curriculum and Assessment). (2008). Assessment in the primary school: guidelines for teachers. Dublin: NCCA.

Newman, E. (1997). Primary teachers’ dilemmas in initial teacher training. Teacher Development, 1(2), 253–268.

Nortvedt, G.A., Wiese, E., Skedsmo, G., Brown, M., Burns, D., McNamara, G., O’Hara, J., Altrichter, H., Fellner, M., Herzog-Punzenberger, B., Nayir, F., & Taneri, P.O. (2020). Aiding culturally responsive assessment in schools in a globalising world. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, (online first), Retrieved February, 3rd, 2020, from https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-020-09316-w

Nusche, D., Shewbridge, C. & Lamhauge Rasmussen, C. (2009). OECD reviews on migrant education: Austria. Accessed 3 Feb 2017, from http://www.oecd.org/austria/44192225.pdf

OECD (2009). OECD toolkit on teaching for diversity. for teaching on diversity. Accessed 5 Sept 2019 from http://www.oecd.org/general/searchresults/?q=Toolkit%20for%20teachers%20of%20diversity

OECD. (2016). Global competency for an inclusive world. Paris: OECD.

OECD. (2019). TALIS 2018 results (Vol. I): teachers and school leaders as lifelong learners. Paris: OECD.

Ovando, C., Collier, V., & Combs, M. (2003). Bilingual and ESL classrooms: teaching multicultural contexts. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Padilla, A. M. (2001). Issues in culturally appropriate assessment. In L. A. Suzuki, J. G. Ponterotto, & P. J. Meller (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural assessment (pp. 5–27). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.