Abstract

Earthquakes cluster in space and time resulting in nonlinear damage effects. We compute earthquake interactions using the Coulomb stress transfer theory and dynamic vulnerability from the concept of ductility capacity reduction. We combine both processes in the generic multi-risk framework where risk scenarios are simulated using a variant of the Markov chain Monte Carlo method. We apply the proposed approach to the thrust fault system of northern Italy, considering earthquakes with characteristic magnitudes in the range ~[6, 6.5], different levels of tectonic loading \(\dot{\tau }\) = {10−4, 10−3, 10−2} bar/year and a generic stock of fictitious low-rise buildings with different ductility capacities μ Δ = {2, 4, 6}. We describe the process’ stochasticity by non-stationary Poisson earthquake probabilities and by binomial damage state probabilities. We find that earthquake clustering yields a tail fattening of the seismic risk curve, the effect of which is amplified by damage-dependent fragility due to clustering. The impact of clustering alone is in average more important than dynamic vulnerability, the spatial extent of the former phenomenon being greater than of the latter one.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Earthquakes are known to cluster in space and time due to stress redistributions in the Earth’s crust (e.g., King 2007). The impact of this clustering on building damage is nonlinear, as the capacity of a structure degrades with increased damage (e.g., Polese et al. 2013; Iervolino et al. 2014). Such physical interactions at both hazard and risk levels are expected to lead to risk amplification toward the tail of the risk curve (e.g., Mignan et al. 2014), which relates to the concepts of extreme event and tail fattening (e.g., Weitzman 2009; Sornette and Ouillon 2012; Foss et al. 2013).

Performance-based seismic assessment consists in quantifying the response of a structure to earthquake shaking using decision variables, such as damage or economic loss. Such procedure is described in the benchmark Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research (PEER) method, summarized by Cornell and Krawinkler (2000). Aftershock probabilistic seismic hazard analysis was added to the PEER method in recent years (Yeo and Cornell 2009), as well as damage-dependent vulnerability (Iervolino et al. 2014). However, these approaches express earthquake clustering analytically with the temporal component defined from the Omori law (see the limits of this law in Mignan (2015, 2016)) and with an ad hoc spatial component. In particular, they do not consider the coupling of large earthquakes on separate fault segments that is observed in Nature.

This coupling can be the association of a great mainshock and its largest aftershock where both events occur on distinct fault segments, such as the 2010 M w 7.1 Canterbury, New Zealand, mainshock and its 2011 M w 6.3 Christchurch aftershock (Zhan et al. 2011). There is also the case of successive large earthquakes occurring on neighboring fault segments and within days or tens of days of each other. Well-known examples include the 2004–2005 M w 9.0–8.7 Sunda megathrust doublet (Nalbant et al. 2005; Mignan et al. 2006), the 1999 M w 7.4–7.1 Izmit and Duzce North Anatolian doublet (Parsons et al. 2000) and the 1811–1812 M w 7.3–7.0–7.5 New Madrid Central United States triplet (Mueller et al. 2004). In contrast to aftershock statistics in which the largest aftershock is about one magnitude below the mainshock magnitude (Bath 1965), clusters of large earthquakes with similar magnitudes are relatively rare but have a high damage potential.

Here, we quantify the expected impact of the spatiotemporal clustering of large earthquakes on seismic risk, considering the additional role of vulnerability increase. By large, we refer to events that occur on distinguishable (and known) fault segments, so roughly with magnitudes greater than 6. Combining explicit interactions between hazardous events with dynamic vulnerability and exposure is the main feature of the generic multi-risk (GenMR) framework (Mignan et al. 2014; Matos et al. 2015). The present work takes advantage of the GenMR framework’s capability to cope with heterogeneous risk processes and describes its conceptual application. We consider as underlying physical processes (1) the Coulomb stress transfer theory (e.g., King et al. 1994; King 2007; Nalbant et al. 2005; Parsons et al. 2000; Mueller et al. 2004; Zhan et al. 2011; Toda et al. 1998; Parsons 2005) and (2) repeated building ductility capacity reduction (e.g., Iervolino et al. 2014) based on simple relationships between interstory drift and spectral acceleration (e.g., Baker and Cornell 2006). While Coulomb stress transfer is well established, other processes could be considered such as fluid migration (e.g., Miller et al. 2004). The choice of the underlying physical processes is independent of the GenMR modeling structure.

For illustration purposes, we consider the thrust fault system of northern Italy and a generic building stock composed of fictitious low-rise buildings of different performances. Note that other fault systems could have been laid below our generic building stock; we considered the one of northern Italy, as the dataset is readily available and detailed. Moreover, the analyzed region recently encountered a doublet of magnitude M ~ 6 earthquakes (the 2012 Emilia-Romagna seismic sequence; Anzidei et al. 2012) with the second event yielding significantly more damage, partly due to buildings rendered more vulnerable following the first shock (the number of homeless people raised from 5000 to 15,000 between the two events; Magliulo et al. 2014). Coulomb stress transfer has already been applied with success to describe the clustering of large earthquakes in Italy, including the 2012 cluster (e.g., Cocco et al. 2000; Ganas et al. 2012). The aim of this study is to provide an overview of the combined effects of earthquake clustering and damage-dependent fragility on seismic risk, in particular on the shape of the seismic risk curve. The method and the risk results apply in principle to any region subject to multiple active faults. The paper is methodological in nature and not a risk study of the Emilia catastrophe, which would require a more elaborate engineering approach to dynamic vulnerability.

2 Method

2.1 Large earthquakes clustering by Coulomb stress transfer

2.1.1 Coulomb stress transfer theory

The phenomenon of earthquake interaction is well established with the underlying process described by the theory of Coulomb stress transfer (e.g., King et al. 1994). In its simplest form, the Coulomb failure stress change is

where Δτ is the shear stress change, Δσ n the normal stress change and μ′ the effective coefficient of friction. Failure is promoted if Δσ f > 0 and inhibited if Δσ f < 0 (see King (2007) for a review). This is not to be confused with rupture propagation due to dynamic stress changes, which may lead to greater earthquakes (Mignan et al. 2015a)

Coulomb stress transfer is generally not considered in seismic hazard assessment except occasionally in time-dependent earthquake probability models where the “clock change” effect of a limited number of historical earthquakes is included (Toda et al. 1998; Field 2007; Field et al. 2009). The conditional probability of occurrence of an earthquake is then expressed through a non-stationary Poisson process as

where N is the number of events expected during Δt. Following Toda et al. (1998),

The first term represents the permanent stress change (so-called clock change) with

where λ 0 is the rate prior to the interaction, Δσ f the stress change and \(\dot{\tau }\) the stressing rate. The second term of Eq. 3 represents the transient stress amplification (Dieterich 1994)

This transient phenomenon is described by Δσ f, the constitutive parameter Aσ and the aftershock duration t a = Aσ/\(\dot{\tau }\) (Dieterich 1994) (see Parsons (2005) for a review).

2.1.2 Sensitivity analysis

The parameter set \(\theta = \{{\Delta {\sigma_{f}}}, \dot{\tau },A\sigma \}\) is defined over the intervals 10−3 ≤ Δσ f ≤ 1 bar, 10−4 ≤ \(\dot{\tau }\) ≤ 10−1 bar/year and 10−2 ≤ Aσ ≤ 10 bar for sensitivity analysis. These intervals are representative ranges of known parameter variations (e.g., King 2007; Catalli et al. 2008; Toda et al. 1998). Figure 1 shows the influence of each one of the parameters on the conditional probability Pr(Δt = 1 year, λ 0 = 10−3 year−1, θ) (Eq. 2) averaged over the ranges of the two remaining free parameters. Δσ f represents the relative local triggering (static stresses decreasing with the inverse of the cubic distance), while \(\dot{\tau }\) controls the absolute regional triggering (being related to the tectonic context).

Sensitivity of the mean conditional probability Pr (Eq. 2) to different values of the parameter set \(\theta = \{ \Delta \sigma_{f} ,\dot{\tau },A\sigma\) with Δt = 1 year and λ 0 = 10−3 year−1 fixed. For the present application (see Sect. 3), we fix Aσ = 0.1 bar and test \(\dot{\tau }\) = {10−4, 10−3, 10−2} bar/year to represent strong, medium and weak clustering

We find that the parameter Aσ has a relatively limited influence on probability changes compared to Δσ f and \(\dot{\tau }\), which show opposite effects compared to each other. A strong earthquake clustering requires a low stressing rate (region-dependent) and/or a high stress change (perturbing earthquake very close to the target fault) (e.g., Parsons 2005). These characteristics remain similar for different values of λ 0. The role of Coulomb stress transfer on seismic risk is investigated in the application to the thrust fault system of northern Italy (see Sect. 3).

2.1.3 GenMR implementation

GenMR simulates N sim multi-risk scenarios based on a variant of the Markov chain Monte Carlo method (Mignan et al. 2014). Each simulation generates a time series in the interval Δt = [t 0, t max] in which events are drawn from a non-stationary Poisson process. It requires as input (1) an n-event stochastic set with identifier Ev i and long-term recurrence rate λ 0(Ev i ) and (2) an n × n hazard correlation matrix (HCM) with fixed conditional probabilities Pr(Ev j | Ev i ) or time-variant conditional probabilities Pr(Ev j |Η(t) = {Ev(t 1), Ev(t 2), …, Ev(t)}), Η being the history of event occurrences up to time t (i.e., process memory). Hazard intensities and damages are introduced in Sect. 2.2.

Let us note λ(EQ j , t k ) the non-stationary rate of target event EQ j at the occurrence time t k of the kth event in the time series, λ 0(EQ j ) = λ(EQ j , t 0) the long-term rate of EQ j and Η(t 0) = {Ø}. Due to the accumulation of permanent stress changes after each earthquake occurrence, a summing iteration of Eq. 4 yields

with Δσ f(EQ i (t k ), EQ j ) the stress change on EQ j due to EQ i and \(\dot{\tau }\)(EQ j ) the stressing rate on the receiver fault of EQ j . Combining Eqs. 2 and 3, we obtain the time-variant HCM with conditional probability of occurrence

The HCM for EQ–EQ interactions (hereafter referred to as HCMEQ–EQ) thus depends solely on the matrix Δσ f(EQ i , EQ j ), the parameter set \(\theta = \{ \dot{\tau },A\sigma \}\) and the history of event occurrences Η defined by the summation term in Eq. 6. Since a ratio \(\Delta \sigma_{\text{f}} /\dot{\tau }\) ~ 50:1 is required to significantly skew occurrence probabilities with confidence great than 80–85 % (Parsons 2005), we only consider Δσ f(EQ i , EQ j ) values that fulfill this condition.

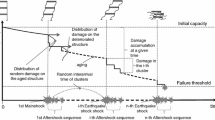

In any given simulated time series (Fig. 2), the occurrence time of independent events is drawn from the uniform distribution with t ∈ [t 0, t max]. If EQ j occurs due to EQ i following Eq. 7, its occurrence time is fixed to t j = t i + ε with ε ≪ Δt. If t j > t max, the event is excluded from the time series. A small ε represents temporal clustering within a time series. Its choice has no significance on the results in the present study since dynamic vulnerability depends on the number of earthquakes in a cluster and not on their time interval (see Sect. 2.2). Temporal processes, such as reparations, are not included (i.e., non-resilient system).

Examples of two simulation sets S 0 and S 1, representing no interaction (null hypothesis H 0) and interactions (H 1), respectively. Each simulation set is composed of N sim time series (or risk scenarios). The second time series is here empty to illustrate the fact that large earthquakes are rare and that many simulation-years “see” no earthquake (for northern Italy, the average return period of large earthquakes is c. 77 years). Modified from Mignan et al. (2014)

Let us now define the null hypothesis H 0 (simulation set S 0) as the case where there is no interaction and the hypothesis H 1 (simulation set S 1) as the case where earthquakes interact with each other (Fig. 2). If Δt ≪ 1/λ 0 in simulation set S 0, time series with more than one earthquake would be much rarer than time series with only one event (i.e., Poisson process). As a consequence, the potential for clock delays (or removal of events) would be much lower than for clock advances (or additions of events) in S 1. With S 1 likely to produce more earthquakes than S 0, the seismic moment rate would not be conserved. If the sum of moment rates \(\sum\nolimits_{i} {\dot{M}_{0i} } = \sum\nolimits_{i} {M_{0i} \lambda_{0i} }\) (Hanks and Kanamori 1979) in S 1 is not in the 3-sigma range of the natural fluctuations observed in S 0, we correct λ 0(Ev i ) of the stochastic event set, such that

with \(\hat{\lambda }\) the estimated rate in a given simulation set. Simulation sets S 0 and S 1 are then regenerated with the modified stochastic event set. This action is repeated until the 3-sigma rule—i.e., until the regional seismic moment rate conservation—is verified (see example in Sect. 3.2). \(\lambda_{0}^{\prime }\) here represents the rate of trigger earthquakes, which is lower than the rate of trigger and triggered earthquakes combined.

2.2 Damage-dependent seismic fragility

2.2.1 Generic building characteristics and damage assessment

We consider a fictitious low-rise building with height H b and fundamental period

with parameters c 1 = 0.075 and c 2 = 3/4 (for moment–resistant reinforcement concrete structures), H b in meters and T b in seconds (see review by Crowley and Pinho 2010). The low-rise building is subjected to the spectral acceleration S a(T b) due to earthquake occurrences. We define the maximum interstory drift ratio ΔEQ as

with a and b empirical parameters (e.g., Baker and Cornell 2006).

We describe the generic capacity curve of the fictitious low-rise building by its stiffness K, yield strength Q and ductility capacity μ Δ (Fig. 3a). Further, we define the mean damage δ as a function f of the drift ratio (or shear deformation) Δ

where n DS is the number of damage states, Δ y = Q/K the yield displacement capacity and Δmax = Δy μ Δ the maximum plastic displacement capacity. The relationship between δ and Δ is assumed linear within the plasticity (or ductility capacity) range. Within the elasticity range, we assume that δ decreases faster toward zero by following a power-law behavior. We fix the number of damage stages (DS), that is, n DS = 5 with DS1 to DS5 representing insignificant, slight, moderate, heavy and extreme damage, respectively (Fig. 3b). Equation 11 indicates that DS1 is most likely at Δ = Δ y and DS5 at Δ = Δmax (e.g., FEMA 1998). We here assume that extreme damage corresponds to building collapse and that the building has a perfectly elasto-plastic behavior.

We then generate fragility curves from the cumulative binomial distribution

for each damage state DS k with 0 ≤ k ≤ n DS (e.g., Lagomarsino and Giovinazzi 2006) (Fig. 3c). Equation 12 represents the uncertainty on the damage state for a given drift ratio, which relates to the concept of imprecise probability (e.g., Caselton and Luo 1992). Note that other formulations could have been used (e.g., for Italy, Faccioli et al. 1999; Dolce et al. 2003; Rasulo et al. 2015).

2.2.2 Concept of damage-dependent fragility

Numerous structural engineering studies deal with damage-dependent fragility (e.g., Polese et al. 2013; Iervolino et al. 2014—and references therein). Most of those studies include extensive nonlinear dynamic analyses and numerical simulations of idealized two- or three-dimensional buildings. The scope of GenMR, as its name indicates, is not to provide an engineering-based platform for actual site-specific multi-risk assessment but a generic framework for a general understanding of hazard interactions and of other dynamical processes of the risk assessment chain. Here, damage-dependent seismic fragility must be viewed from that overarching perspective where transparency is key and a given degree of abstraction is required (Mignan et al. 2014, 2016a, 2016b; Komendantova et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2015; Matos et al. 2015). Albeit simplified, the procedure of deriving damage-dependent seismic fragility is not incompatible with engineering approaches and when integrated with the GenMR approach can in fact provide a blueprint for future region- or site-specific applications.

Conceptually, the capacity of a structure degrades with increased damage. We here consider, as source of degradation, the decrease in the plasticity range (Δy, Δmax2 = Δmax1−Δ r ) due to the residual drift ratio

This process yields a shift of the fragility curves toward lower Δ values (i.e., increased vulnerability). This is illustrated in Fig. 4 where the evolution of fragility curves per damage state is shown for different pre-damage levels. The solid curves represent the latent vulnerability curves, which are only altered for a damage state equal or greater to DS2 (DS1 does not produce any residual drift in average). The role of changes in stiffness and building resonance period—not included in this study—is discussed in Sect. 3.3.

Damage-dependent fragility curves per damage state (different plots) for different pre-damage levels (different curves). The residual drift ratio (Eq. 13) is here directly defined from the pre-damage level, as shown by the evolution of the ductility capacity range in the top left plot

2.2.3 Sensitivity analysis

We investigate the role of repeated earthquake shaking on the damage time series of generic low-rise buildings of different structural performances. We define low, medium and high levels of seismic performance of low-rise buildings due to increased plastic displacement capacity by the ductility capacity values μ Δ = {2, 4, 6}, respectively. We analyze the N-time repeat of an earthquake producing a constant ΔEQ = 1.1Δ y , which represents insignificant damage (DS1) for the initial building (for any tested μ Δ value). We consider the stochastic damage process described by the random variables

and

where t i is the occurrence time of the earthquake with 1 ≤ i ≤ N, Δmax(t 0) the initial maximum plastic displacement capacity and δ = f(Δ) (Eq. 11). Results from 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations are shown in Fig. 5. Firstly, the median curves (solid black curves) indicate that the building of poor performance (μ Δ = 2) is the most prone to damage amplification, while no amplification is observed in average for the buildings of medium and high performances (μ Δ = {4, 6}) for N ≤ 10. Secondly, the first and third quartiles (dashed curves) indicate that the results are highly variable across simulations due to the stochasticity of the damage process, as described by the binomial distribution. Let us note that the repeat of a multitude of events producing insignificant damage (here ΔEQ = 1.1Δ y ) is expected in aftershock and induced seismicity sequences (e.g., Iervolino et al. 2014; Mignan et al. 2015b). In the case of large earthquake clustering, N is expected to remain small but with events more likely to directly produce moderate to high damage, thereby facilitating damage amplification (see Sect. 3).

Sensitivity of damage to different building performances (low, medium and high, i.e., ductility capacity values μ Δ = 2, 4 and 6, respectively) for the n EQ-time repeat of an earthquake producing a constant ΔEQ = 1.1Δ y , which represents insignificant damage (DS1) for the initial building (for any tested μ Δ value). Gray curves represent the different simulations where the damage state is drawn from the Binomial distribution (Eq. 14). Black solid and dashed curves represent the median and first and third quartiles, respectively

2.2.4 GenMR implementation

For each realization of a stochastic event EQ i in GenMR, a spatial footprint of the hazard intensity \(\tilde{I}\) is generated such that

with I the median of the expected hazard intensity and σ I its standard deviation in the log10 scale (see example of ground motion prediction equation in Sect. 3.1.3). The footprint is computed on the exposure grid (x, y), such that a hazard intensity value is attributed to each building location of the considered portfolio. The damage state \(\widetilde{\text{DS}}\left( {x,y} \right)\) is then computed from Eq. 14 with ΔEQ computed from Eq. 10. It means that three stochastic processes are considered in GenMR: the earthquake occurrence (non-stationary Poisson), the hazard intensity (lognormal) and the damage state (binomial).

Each location of coordinates (x,y) represents one building with the four attributes T b, Δ y , μ Δ and Δ r . The first three parameters remain constant over time, while the fourth is a function of ΔEQ(EQ i ) (Eq. 13). For each stochastic event EQ i (t k ), the loss is defined as the total number N DS4+ of buildings with damage state DS4 or DS5 in the exposure grid. Any given simulated time series is thus defined by a list of events with identifier EQ i , time of occurrence t ∈ [t 0, t max] and produced loss N DS4+ (the parent earthquake, if any, is provided as metadata).

3 GenMR application

We provide an application of the proposed procedure tailored for a region in northern Italy by considering available seismogenic faults and a generic building portfolio. It shall be noted that the application is an illustrative example without considering the true building stock of the region. Such inclusion requires information and accuracy of the built environment of the region beyond the scope of the present investigation. However, the use of low-rise buildings with various seismic performance levels (i.e., low, medium and high) provides a suitable starting point, as they represent the majority of residential building of the Italian residential buildings. Additional building typologies could be added for analysis that is more complex if exposure data are available. Thus, given inherent limitations (see Sect. 3.3), this application remains theoretical and a summary of its main procedural steps and elements is presented in the next sections.

3.1 Inputs

3.1.1 Stochastic event set

We define a set of n = 30 stochastic events representing characteristic earthquakes on idealized straight fault segments. These segments are simplified versions of the 20 shallow thrust composite faults defined in the 2013 European Seismic Hazard Model (hereafter ESHM13) for northern Italy. This model represents the latest seismic hazard model for the European–Mediterranean region (Woessner et al. 2015; Basili et al. 2013; Giardini et al. 2013). Table 1 lists the ESHM13 identifier, slip rate \(\dot{s}\), dip, rake and maximum magnitude M max of the 20 ESHM13 composite sources as well as the length L, width W, characteristic magnitude M char and long-term rate λ 0 = λ(t 0) of the 30 stochastic events. Figure 6 shows the map of northern Italy and the correspondence between the stochastic events EQ i and the ESHM13 sources. Only lateral triggering is considered on these simplified fault geometries (Sect. 3.1.2). Potential interactions in the deeper parts of the crust are not included.

Surface projection of the 20 ESHM13 shallow thrust composite faults in northern Italy (numbered ITCxxxx). The fault traces were simplified to series of straight lines for Coulomb stress transfer calculations. Stochastic earthquakes are defined as the characteristic earthquakes hosted by the 30 straight segments (numbered 1–30). The smaller ~10-km-wide patches represent the spatial resolution used for Coulomb stress transfer calculations before averaging. Colors represent the stress changes Δσ f(EQ1, EQ j ) due to event EQ1 (gray segment) on all other segments (i.e., hosts of EQ j )

M char is derived from the seismic moment M 0 [dyn.cm]

with c = 16.05, d = 1.5 (Hanks and Kanamori 1979) and

with A = LW [m2] (Yen and Ma 2011; see Stirling et al. (2013) for a review). It follows that M char ∈ [6.1, 6.6] in the present case.

The rate λ 0 is derived from the long-term slip rate \(\dot{s}\) and fault displacement u following Wesnousky (1986)

weighted by the number n of stochastic events EQ k possible on a same ESHM13 source (Table 1). It yields the total characteristic earthquake rate \(\sum {\lambda_{0} = 0.013}\) or in average one M char earthquake every ~77 years somewhere in northern Italy. The fault displacement u (also used in stress transfer calculations) is obtained from

with the shear modulus μ = 3.2 1011 dyn/cm2 (Aki 1966).

3.1.2 HCMEQ–EQ

The HCMEQ–EQ is built from the matrix of Coulomb stress changes Δσ f(EQ i , EQ j ), here computed using the Coulomb 3 software (Lin and Stein 2004; Toda et al. 2005, 2011). The inputs to the software are the effective coefficient of friction μ′ = 0.4, the fault segment characteristics (Fig. 6; Table 1) and the earthquake slip u [m] (Eq. 20). Δσ f [bars] is computed on ~10-km-wide dislocation patches and then averaged over the full fault segments. Figure 6 shows as example the spatial distribution of Δσ f(EQ1, EQ j ), which indicates that triggering occurs principally at the tips of the trigger segment on segments of similar strike and mechanism (all reverse).

The impact of Δσ f on clustering patterns and of \(\dot{\tau }\) on clustering levels is investigated in Sect. 3.2.1. It should be noted that the maximum stress changes, computed on segments closest to a rupture, rarely exceed 1 bar. The stresses released on ruptured segments are of the order of several bars. For central Italy, Catalli et al. (2008) obtained 7 × 10−5 ≤ \(\dot{\tau }\) ≤ 7 × 10−3 bar/year based on seismicity rates and Aσ = 0.4 bar. For the present application, we fix Aσ = 0.1 bar and test \(\dot{\tau }\) = {10−4, 10−3, 10−2} bar/year to represent strong, medium and weak clustering (Fig. 1). Loose constraints on the regional value of \(\dot{\tau }\) (e.g., Catalli et al. 2008) do not allow us to determine which clustering regime is the most likely in northern Italy.

3.1.3 Generic building characteristics and damage assessment

We consider a generic model of low-rise buildings with height H b ~ 3.8 m and fundamental period T b ~ 0.2 s (Eq. 9). A yield displacement capacity Δ y of 0.01 is adopted as a reference value for reinforced concrete buildings (e.g., Panagiotakos and Fardis 2001). We test three different seismic performances, i.e., low, medium and high of low-rise buildings, represented by different ductility capacity values μ Δ = {2, 4, 6} (e.g., FEMA 1998), which lead to plastic displacement capacities Δmax = {0.02, 0.04, 0.06}. Let us note that a low ductility capacity is expected in the existing historic building portfolio of northern Italy (and of Europe in general). Using different ductility capacities allows us to approximate variations observed in structures of different ages (residential houses from the 1960s to present) and different performance levels (e.g., industrial buildings).

The damage to the building is evaluated from the interstory drift ratio (Eq. 11 or 14) estimated itself from the spectral acceleration S a(T b) produced by the earthquake (Eq. 10). We fix the parameters of Eq. 10 to b = 1 (e.g., Baker and Cornell 2006) and a = log(Δ y ) + log(μ Δ) − log(Sacollapse(T b, μ Δ)) = −3.2, assuming that a spectral acceleration Sacollapse = 1 g leads to the collapse (DS5) of buildings of moderate performance (μ Δ = 4). This is a strong assumption, which controls the overall level of damage estimated in this study. However, it provides a reasonable and transparent calibration of damage for our structural model of the fictitious low-rise buildings. Let us note that a = −3.2 is close to existing values (e.g., Baker and Cornell 2006). For μ Δ = 2 or 6, our calibration leads to Sacollapse = 0.5 g and 1.5 g, respectively.

We compute S a(T b) for each stochastic event using the ground motion prediction equation (GMPE) of Akkar and Bommer (2010)

with S a in cm/s2, M = M char the earthquake magnitude (Table 1), R jb the distance to the fault surface trace in km, S S = 1 and S A = 0 (soft instead of stiff soil) and F N = 0 and F R = 1 (reverse instead of normal faulting). The fitting parameters b 1–10, which depend on period T, are given in Akkar and Bommer (2010). We computed S a(T b) on a regular grid of generic buildings spaced every 0.01° (~1 km) in longitude and latitude in northern Italy.

Figure 7 shows the hazard and damage footprints for EQ30 and for the three building performances. The left column presents the median estimates, while the right column presents stochastic realizations (or scenarios), which include the spatial correlation of the ground motion fields (Eq. 16) and uncertainties at the damage levels (Eq. 14). In Eq. 16, σ I is defined as the intra-event sigma, as provided in Akkar and Bommer (2010). The use of intra-event sigma prevents the inflation of the ground motion fields, which in turn might introduce bias to the risk estimates (Jayaram and Baker 2009). Only stochastic versions are considered in GenMR. The role of damage-dependent fragility on damage footprints is investigated in Sect. 3.2.2.

Hazard and damage spatial footprints of event EQ30. The stochastic version of hazard represents the spatial correlation of the ground motion fields defined by the intra-event sigma (Eq. 16). The stochastic version of damage represents imprecise probabilities described from a binomial distribution (Eq. 14) (on top of the random ground motion field). Low, medium and high building performances correspond to ductility capacity values μ Δ = 2, 4 and 6, respectively

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Hazard characteristics of earthquake clustering

Four simulation sets are produced, each composed of N sim = 106 simulations. The simulation set S 0 represents the null hypothesis H 0 that earthquakes are independent following a Poisson process. The simulation sets S 1, S 2 and S 3 represent the hypothesis H 1 that earthquakes interact with each others following the Coulomb stress transfer theory, respectively, with \(\dot{\tau }\) = {10−4, 10−3, 10−2} bar/year.

We verify that the total seismic moment rate \(\dot{M}_{0}\) is conserved in all simulation sets by first evaluating the natural variation of \(\dot{M}_{0} \left( {H_{0} } \right)\) in 1000 iterations of S 0. The resulting normalized distribution \(\dot{M}_{0} \left( {H_{0} } \right)/\sum\nolimits_{i} {M_{0i} \lambda_{0i} }\), with λ 0i the long-term expected rate of EQ i (Table 1), is shown in Fig. 8a. We then consider that the total seismic moment rate is conserved if the values \(\dot{M}_{0} \left( {S_{1} } \right)\), \(\dot{M}_{0} \left( {S_{2} } \right)\) and \(\dot{M}_{0} \left( {S_{3} } \right)\) normalized by \(\sum\nolimits_{i} {M_{0i} \lambda_{0i} }\) remain within ±3σ(H 0) = 0.025 (dotted lines on Fig. 10a). For S 1 and S 2 for which it is not the case, the long-term rate \(\lambda_{0}^{\prime }\) is corrected by removing the implicit role of interactions from λ 0 (Eq. 8) (dashed lines on Fig. 8a). It assumes that the λ 0 values derived from slip rates in ESHM13 represent the long-term behavior of earthquakes in northern Italy and include the phenomenon of clustering.

Earthquake clustering statistics: a distribution of the natural variation of the normalized total seismic moment rate \(\dot{M}_{0} \left( {H_{0} } \right)/\sum\nolimits_{i} {M_{0i} \lambda_{0i} }\) in 1000 iterations of simulation set S 0 where earthquakes are independent. The long-term rate is corrected to \(\lambda_{0}^{\prime }\) by removing the role of interactions from λ 0 (Eq. 8) for sets S 1 and S 2 in order for the normalized seismic moment rate to remain within ±3σ(H 0) = 0.025 (dotted lines) (i.e., seismic moment rate conservation); b distribution of the number of earthquakes per annual simulation, best fitted by a Poisson process for H 0 (no interactions) and by a negative binomial process for H 1 (earthquake clustering). Numbers correspond to the amount of cases in 106 simulations

Figure 8b shows the distribution of the number of earthquakes N per year for simulation sets S 0 and S 1. The distribution is best fitted by a Poisson process for H 0 and by a negative binomial process for H 1 with index of dispersion \(\phi = {\text{Var}}\left( {n_{\text{EQ}} } \right)/\overline{{n_{\text{EQ}} }} = \left\{ {1.38,1.07,1.01} \right\}\) for sets S 1, S 2 and S 3, respectively (combining maximum likelihood estimation and Akaike information criterion). The values taken by ϕ verify that the degree of clustering (or over-dispersion) increases with decreasing stressing rate. This represents an instance of hazard migration (or hazard clustering), as described at the abstract level by Mignan et al. (2014). In the case of strong clustering (S 1), earthquake doublets become relatively common in comparison with the null hypothesis of no earthquake interaction. In rare cases, earthquake triplets and even quadruplets are also observed. Only results from S1 (\(\dot{\tau }\) = 10−4 bar/year) are considered in the rest of this study to illustrate the potential impact of earthquake clustering on seismic risk.

Let us note that clusters correspond to combinations of individual ruptures on a same fault or on several neighbor faults (i.e., where stress increases are the strongest). Some of the longest observed chains of earthquakes exemplify this characteristic with EQ12 → EQ13 → EQ14 → EQ6, EQ25 → EQ26 → EQ5 or EQ4 → EQ3 → EQ29 (see Fig. 6).

3.2.2 Risk characteristics of earthquake clustering (including dynamic vulnerability)

We now analyze additional simulation sets, which include loss values defined by the metric N DS4+ for low, medium and high building performance, respectively, μ Δ = {2, 4, 6}. Hypothesis H1 represents the case of strong earthquake clustering with constant vulnerability. Hypothesis H2 also includes strong earthquake clustering but with dynamic vulnerability. All simulation sets are compared to their respective null hypotheses H0 where earthquake is independent and buildings have the same performance.

Figure 9 shows seismic risk curves with losses defined by the metric N DS4+. They are computed for the hypotheses H 0 (dotted curves), H 1 (dashed curves) and H 2 (solid curves) and for the three building performances (low, medium and high represented in brown, red and orange, respectively). Independently of the building performance, an increase is observed at the tail of the risk curve for both H1 and H2, compared to H 0. The increase is more notable for earthquake clustering than for dynamic vulnerability. However, the impact of damage-dependent fragility increases with increasing losses, in agreement with the concept of risk amplification (Mignan et al. 2014). This tail fattening is representative of extreme seismic catastrophes, which in the present case would be large earthquake clusters combined with nonlinear vulnerability increase.

Seismic risk curves defined as the annual probability of exceeding a given N DS4+ threshold, N DS4+ being the number of fictitious buildings experiencing damage state DS4 (heavy damage) or DS5 (extreme damage or collapse). Results are shown for the three building performances (low, medium and high) and for the three hypotheses H 0 (no interaction), H 1 (earthquake clustering) and H 2 (earthquake clustering and damage-dependent fragility). The tail of the risk curve fattens from H 0 to H 2 due to the addition of multi-risk processes

This tail fattening, although non-negligible, increases losses in the present example of only two third at most compared to the Poisson hypothesis for a fixed return period. It means that the absolute impact of earthquake clustering remains limited in our generic application, even when the clustering level is high and building performance poor. Let us note that the increase in risk is here compared to the Poisson case where clusters of events can occur randomly. This case is rarely considered in seismic risk analysis (e.g., Bazzuro and Luco 2005) although random clusters are known to be fat-tail phenomena (see Foss et al. (2013) for a review). Comparing to 1-event occurrences only, losses can almost triple when dynamic effects are considered, while they only double if earthquakes are independent and damage static. These values should, however, be taken with caution. Overall, a detailed hazard and risk assessment that would include earthquake clustering seems unwarranted for common buildings. Only for critical infrastructures do the dynamic effects start to have an impact on seismic risk (i.e., at the tail). The present results are generic in nature, and only site-specific analyses will allow investigating to what extent this tail fattening is significant for specific portfolios.

The relative impacts of earthquake clustering and dynamic vulnerability are illustrated in Fig. 10 where damage maps with and without damage-dependent fragility are compared in the case of the triplet EQ12 → EQ13 → EQ14. To improve visualization, we show the mean damage δ evolution of moderate performance buildings without spatial hazard correlation. We first see that earthquake clustering has the strongest impact since it multiplies roughly the amount of expected damage by the number of earthquakes in the cluster compared to the damage due to only one individual event in the null hypothesis. While the increase in damage due to damage-dependent vulnerability is clear from Figs. 9 and 10, it remains a limited phenomenon localized at fault segment intersections (where hazard footprints overlap).

It is the clustering process, as illustrated in Fig. 11, that explains the unusual step-like structure of the seismic risk curves of Fig. 9. The usual concave shape observed in log plots is characteristic of a homogeneous process where risk is due to an N-event cluster (or N-cluster) with N constant (note again that N = 1 in standard seismic risk analyses). This is best described in the Poisson case where we observe “standard” risk curves for the 1-event and 2-events systems, separated by a transitional risk curve. This transitional phase of the risk curve corresponds to the loss range where 1-event and 2-event clusters are mixed. This pattern is observed systematically, with the dynamic risk curve showing additional jumps for the transitions between 2- and 3-event clusters and between 3- and 4-event clusters.

3.3 Limitations

In the analysis of earthquake interactions, we assumed a simplified fault geometry (Fig. 6), a constant displacement slip model and an effective coefficient of friction μ′ = 0.4. Average fault characteristics (strike, rake, dip) were taken from the ESHM13 database. King (2007) showed that small errors in dip and strike, such as simplified fault geometry, do not significantly impact the stress values except in the near field. Zhan et al. (2011) observed that different slip models only result in significant differences in the near field. Near-field analysis is important for the study of the distribution of small aftershocks but not so for the study of fault segment coupling. Parsons (2005) investigated the role of numerous parameters, including the friction coefficient, rake, dip and slip model, on earthquake probability estimates. The author concluded that stress transfer modeling carries significant uncertainty. In agreement with Parsons (2005), we only considered the case \(\Delta \sigma_{\text{f}} /\dot{\tau }\) ≥ 50:1 to limit the analysis to significant stress changes.

For seismic hazard assessment, the attribution of magnitudes and rates was based on standard methods (Aki 1966; Hanks and Kanamori 1979) and the GMPE selection on recent and well-established results (Akkar and Bommer 2010). However, we solely considered characteristic earthquakes (M > 6.0) while classical probabilistic seismic hazard assessment (PSHA) often considers the Gutenberg–Richter law or a combination of both Gutenberg–Richter and characteristic models (e.g., Field et al. 2009; Basili et al. 2013). Moreover, the choice of a different GMPE will yield different outcomes, as well as a different sigma (i.e., total rather than intra-event) as ground motion uncertainties (both epistemic and aleatory) are leading factors in seismic hazard assessment (e.g., Mignan et al. 2015b; Marzocchi et al. 2015). Our choices were made for sake of simplicity and transparence. They limit the number of scenarios considered, provide a clear constraint on fault segment limits and avoid cumbersome computations involving floating ruptures (within and across fault segments) and logic trees. Note that while the Gutenberg–Richter power law naturally leads to a fat tail of the seismic risk curve, consideration of earthquake interactions and dynamic vulnerability would make this tail fatter.

Other simplifications are in the structural damage analysis, including damage calibration and damage-dependent fragility curve derivation. Damage calibration (parameters a and b in Eq. 10) is highly approximate but remains reasonable in the context of a fictitious low-rise building with generic characteristics. The impact of our choice is clearly illustrated on the damage maps of Fig. 7. The definition of fragility curves is based on the fundamental link between building capacity curve and expected damage, in agreement with existing recommendations (e.g., FEMA 1998; Lagomarsino and Giovinazzi 2006). Damage-dependent vulnerability is here controlled by the decrease in the ductility range, which is known to be the main process of structure deterioration (e.g., Iervolino et al. 2014). However, other parameters, such as the stiffness and the strength of the building, also evolve with increasing damage (FEMA 1998; Polese et al. 2013). One could, for instance, consider the decrease in stiffness K′ = λ K K with the generic reduction factor λ K = 1.2−0.2δ, which can be derived from the FEMA (1998) guidelines. This material property change (additional cracks) additionally influences the effective period of the building

(FEMA 1998). Due to the non-monotonic behavior of S a(T b), the influence of stiffness reduction on cumulated damage is non-trivial. We consider that using the reduction in the ductility capacity, as sole engineering demand parameter, is reasonable (e.g., Iervolino et al. 2014) in the scope of illustrating the concept of dynamic vulnerability. Building-specific applications would, however, require more advanced structural analyses (e.g., Polese et al. 2013).

4 Conclusions

We have described how to combine spatiotemporal clustering of large earthquakes and dynamic vulnerability in the generic multi-risk (GenMR) framework to quantify seismic risk. With an illustrative application to the thrust fault system of northern Italy, we have shown that consideration of these two physical processes yields a fattening of the tail of the seismic risk curve (Fig. 9). The relative impact of clustering alone is in average more important than dynamic vulnerability since earthquake clustering on neighboring fault segments significantly extends the spatial hazard footprint while dynamic vulnerability has localized effects at the intersections of fault segments. Our results are in agreement with the general aspects of multi-risk (e.g., Mignan et al. 2014). With the risk curve being populated with more extreme scenarios when interactions at the hazard and risk levels are considered, its tail becomes fatter.

While earthquake clustering is likely to impact spatially extended infrastructures or distributed portfolios, damage-dependent vulnerability is more likely to impact elements localized at fault intersections (Fig. 10). This shows the need for the definition of an exposure topology (e.g., local versus extended, system connectivity) to clarify what are the risks most relevant to each exposure class. Although obvious here, defining topologies of exposure—but also of multi-risk processes—shall help better understanding and better mitigating increasingly complex risks, which are defined from multiple hazard interactions and from other dynamical processes in the system at risk. The observation of transitional phases in the dynamic risk curves (Fig. 11) also highlights the increasing complexity of the processes in play and the non-trivial behavior of risk. Although well documented in the case of random processes (e.g., Foss et al. 2013), this concept should be generalized to the broader context of multi-risk processes.

References

Aki K (1966) 4. Generation and Propagation of G Waves from the Niigata Earthquake of June 16, 1964. Part 2. Estimation of earthquake moment, released energy, and stress-strain drop from the G wave spectrum. Bull Earthq Res Inst 44:73–88

Akkar S, Bommer JJ (2010) Empirical equations for the prediction of PGA, PGV, and spectral accelerations in Europe, the Mediterranean region, and the Middle East. Seismol Res Lett 81:195–206. doi:10.1785/gssrl.81.2.195

Anzidei M, Maramai A, Montone P (2012) Preface to: the Emilia (northern Italy) seismic sequence of May–June, 2012: preliminary data and results. Annals Geophys 55:515. doi:10.4401/ag-6232

Baker JW, Cornell CA (2006) Which spectral acceleration are you using? Earthq Spectr 22:293–312

Basili R, et al. (2013) The European Database of Seismogenic Faults (EDSF) compiled in the framework of the project SHARE, doi:10.6092/INGV.IT-SHARE-EDSF, available at: http://diss.rm.ingv.it/share-edsf/(last. Assessed Sep 2014)

Bath M (1965) Lateral inhomogeneities of the upper mantle. Tectonophysics 2:483–514

Bazzuro P, Luco N (2005) Accounting for uncertainty and correlation in earthquake loss estimation, ICOSSAR, Augusti G, Schuëller GI, Ciampoli, M (Eds), Millpress, Rotterdam, p 2687–2694

Caselton WF, Luo W (1992) Decision making with imprecise probabilities: dempster-shafer theory and application. Water Resour Res 28:3071–3083

Catalli F, Cocco M, Console R, Chiaraluce L (2008) Modeling seismicity rate changes during the 1997 Umbria-Marche sequence (central Italy) through a rate-and state-dependent model. J Geophys Res 113:B11301. doi:10.1029/2007JB005356

Cocco M, Nostro C, Ekström G (2000) Static stress changes and fault interaction during the 1997 Umbria-Marche earthquake sequence. J Seismol 4:501–516

Cornell CA, Krawinkler H (2000) Progress and challenges in seismic performance assessment. PEER Cent News 3(2):1–4

Crowley H, Pinho R (2010) Revisiting Eurocode 8 formulae for periods of vibration and their employment in linear seismic analysis. Earthq Eng Str Dyn 39:223–235. doi:10.1002/eqe.949

Dieterich J (1994) A constitutive law for rate of earthquake production and its application to earthquake clustering. J Geophys Res 99:2601–2618

Dolce M, Masi A, Marino M, Vona M (2003) Earthquake damage scenarios of the building stock of potenza (Southern Italy) including site effects. Bull Earthq Eng 1:115–140. doi:10.1023/A:1024809511362

Faccioli E, Pessina V, Calvi GM, Borzi B (1999) A study on damage scenarios for residential buildings in Catania city. J Seismol 3:327–343. doi:10.1023/A:1009856129016

FEMA (1998) FEMA 306: evaluation of earthquake damaged concrete and masonry wall buildings—basic procedures manual. Federal Emergency Management Agency, Washington DC 250 pp

Field EH (2007) A summary of previous working groups on california earthquake probabilities. Bull Seismol Soc Am 97:1033–1053. doi:10.1785/0120060048

Field EH et al (2009) Uniform california earthquake rupture forecast, version 2 (UCERF 2). Bull Seismol Soc Am 99:2053–2107. doi:10.1785/0120080049

Foss S, Korshunov D, Zachary S (2013) An introduction to heavy-tailed and subexponential distributions. Springer, 2nd edition, doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-7101-1, pp 157

Ganas A, Roumelioti Z, Chousianitis K (2012) Static stress transfer from the May 20, 2012, M 6.1 Emilia-Romagna (northern Italy) earthquake using a co-seismic slip distribution model. Ann Geophys 55:655–662

Giardini D et al (2013) Seismic Hazard harmonization in Europe (SHARE): online data. Resource. doi:10.12686/SED-00000001-SHARE

Hanks TC, Kanamori H (1979) A moment magnitude scale. J Geophys Res 84:2348–2350

Iervolino I, Giorgio M, Chioccarelli E (2014) Closed-form aftershock reliability of damage-cumulating elastic-perfectly-plastic systems. Earthq Eng Str Dyn 43:613–625. doi:10.1002/eqe/2363

Jayaram N, Baker JW (2009) Correlation model for spatially distributed ground-motion intensities. Earthq Eng Str Dyn 38:1687–1708

King GCP (2007) Fault interaction earthquake stress changes, and the evolution of seismicity. Treatise Geophys 4:225–255

King GCP, Stein RS, Lin J (1994) Static stress changes and the triggering of earthquakes. Bull Seismol Soc Am 84:935–953

Komendantova N, Mrzyglocki R, Mignan A, Khazai B, Wenzel F, Patt A, Fleming K (2014) Multi-hazard and multi-risk decision-support tools as a part of participatory risk governance: feedback from civil protection stakeholders. Int J. Disaster Risk Reduct 8:50–67. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2013.12.006

Lagomarsino S, Giovinazzi S (2006) Macroseismic and mechanical models for the vulnerability and damage assessment of current buildings. Bull. Earthq Eng 4:415–443. doi:10.1007/s10518-006-9024-z

Lin J, Stein RS (2004) Stress triggering in thrust and subduction earthquakes, and stress interaction between the southern San Andreas and nearby thrust and strike-slip faults. J Geophys Res 109:B02303. doi:10.1029/2003JB002607

Liu Z, Nadim F, Garcia-Aristizabal A, Mignan A, Fleming K, Luna BQ (2015) A three-level framework for multi-risk assessment. Georisk: Assess Manag Risk Eng Syst Geohazards 9:59–74. doi:10.1080/17499518.2015.1041989

Magliulo G, Ercolino M, Petrone C, Coppola O, Manfredi G (2014) The Emilia earthquake: seismic performance of precast reinforced concrete buildings. Earthq Spectr 30:891–912

Marzocchi W, Taroni M, Selva J (2015) Accounting for epistemic uncertainty in PSHA: logic tree and ensemble modeling. Bull Seismol Soc Am. doi:10.1785/0120140131

Matos JP, Mignan A, Schleiss AJ (2015), Vulnerability of large dams considering hazard interactions: conceptual application of the generic multi-risk framework, Proceedings of the 13th ICOLD Benchmark Workshop on the numerical analysis of dams, Lausanne, Switzerland, pp 285–292

Mignan A (2015) Modeling aftershocks as a stretched exponential relaxation. Geophys Res Lett. 42:9726–9732. doi:10.1002/2015GL066232

Mignan A (2016) Revisiting the 1894 omori aftershock dataset with the stretched exponential function. Seismol Res Lett. doi:10.1785/0220150230

Mignan A, King G, Bowman D, Lacassin R, Dmowska R (2006) Seismic activity in the Sumatra-Java region prior to the December 26, 2004 (M w = 9.0–9.3) and Mar 28, 2005 (M w = 8.7) earthquakes. Earth Planet Sci Lett 244:639–654. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2006.01.058

Mignan A, Wiemer S, Giardini D (2014) The quantification of low-probability–high-consequences events: part I. A generic multi-risk approach. Nat Hazards 73:1999–2022. doi:10.1007/s11069-014-1178-4

Mignan A, Danciu L, Giardini D (2015a) Reassessment of the maximum fault rupture length of strike-slip earthquakes and inference on Mmax in the Anatolian Peninsula, Turkey. Seismol Res Lett 86:890–900. doi:10.1785/0220140252

Mignan A, Landtwing D, Kästli P, Mena B, Wiemer S (2015b) Induced seismicity risk analysis of the 2006 Basel, Switzerland, enhanced geothermal system project: influence of uncertainties on risk mitigation. Geothermics 53:133–146. doi:10.1016/j.geothermics.2014.05.007

Mignan A, Komendantova N, Scolobig A, Fleming K (2016a), Multi-risk assessment and governance, chapter 16, handbook of disaster risk reduction and management, World Sci. Press & Imperial College Press, London (in press)

Mignan A, Scolobig A, Sauron A (2016b) Using reasoned imagination to learn about cascading hazards: a pilot study. Disaster Prev Manag 25:329–344. doi:10.1108/DPM-06-2015-0137

Miller SA, Collettini C, Chiaraluce L, Cocco M, Barchi M, Kaus BJP (2004) Aftershocks driven by a high-pressure CO2 source at depth. Nature 427:724–727

Mueller K, Hough SE, Bilham R (2004) Analysing the 1811–1812 New Madrid earthquakes with recent instrumental recorded aftershocks. Nature 429:284–288

Nalbant SS, Steacy S, Sieh K, Natawidjaja D, McCloskey J (2005) Earthquake risk on the Sunda trench. Nature 435:756–757

Panagiotakos TB, Fardis MN (2001) Deformations of reinforced concrete members at yielding and ultimate. ACI Struct J 98:135–148

Parsons T (2005) Significance of stress transfer in time-dependent earthquake probability calculation. J Geophys Res. doi:10.1029/2004JB003190

Parsons T, Toda S, Stein RS, Barka A, Dieterich JH (2000) Heightened odds of large earthquakes near istanbul: an interaction-based probability calculation. Science 288:661–665

Polese M, Di Ludovico M, Prota A, Manfredi G (2013) Damage-dependent vulnerability curves for existing buildings. Earthq Eng Str Dyn 42:853–870. doi:10.1002/eqe.2249

Rasulo A, Testa C, Borzi B (2015), Seismic risk analysis at Urban scale in Italy, computational science and its applications—ICCSA 2015, 9157, pp 403–414

Sornette D, Ouillon G (2012) Dragon-kings: mechanisms, statistical methods and empirical evidence. Eur Phys J Spec Top 205:1–26. doi:10.1140/epjst/e2012-01559-5

Stirling M, Goded T, Berryman K, Litchfield N (2013) Selection of earthquake scaling relationships for seismic-hazard analysis. Bull Seismol Soc Am 103:2993–3011. doi:10.1785/0120130052

Toda S, Stein RS, Reasenberg PA, Dieterich JH, Yoshida A (1998) Stress transferred by the 1995 M w = 6.9 Kobe, Japan, shock: effect on aftershocks and future earthquake probabilities. J Geophys Res 103:24543–24565

Toda S, Stein RS, Richards-Dinger K, Bozkurt S (2005) Forecasting the evolution of seismicity in southern California: Animations built on earthquake stress transfer. J Geophys Res. doi:10.1029/2004JB003415

Toda S, Stein RS, Sevilgen V, Lin J (2011) Coulomb 3.3 Graphic-rich deformation and stress-change software for earthquake, tectonic, and volcano research and teaching—user guide, U.S. geological survey open-file report 2011-1060, pp 63, available at http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2011/1060. Assessed Jan 2015

Weitzman ML (2009) On modelling and interpreting the economics of catastrophic climate change. Rev Econ Stat 91:1–19

Wesnousky SG (1986) Earthquakes, Quaternary faults, and seismic hazard in California. J Geophys Res 91:12587–12631

Woessner J, Danciu L, Giardini D et al (2015) The 2013 European seismic hazard model: key components and results. Bull Earthq Eng. doi:10.1007/s10518-015-9795-1

Yen Y-T, Ma K-F (2011) Source-scaling relationship for M 4.6–8.9 earthquakes, specifically for earthquakes in the collision zone of Taiwan. Bull Seismol Soc Am 101:464–481. doi:10.1785/0120100046

Yeo GL, Cornell CA (2009) A probabilistic framework for quantification of aftershock ground-motion hazard in California: methodology and parametric study. Earthq Eng Str Dyn 38:45–60. doi:10.1002/eqe.840

Zhan Z, Jin B, Wei S, Graves RW (2011) Coulomb stress change sensitivity due to variability in mainshock source models and receiving fault parameters: a case study of the 2010–2011 Christchurch, New Zealand, earthquakes. Seismol Res Lett 82:800–814. doi:10.1785/gssrl.82.6.800

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to three anonymous reviewers for their comments. The research leading to these results has been supported by the “Harmonized approach to stress tests for critical infrastructures against natural hazards” (STREST) project, funded by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme [FP7/2007–2013] under Grant Agreement Number 603389 and by the Swiss Competence Center for Energy Research–Supply of Electricity (SCCER-SoE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mignan, A., Danciu, L. & Giardini, D. Considering large earthquake clustering in seismic risk analysis. Nat Hazards 91 (Suppl 1), 149–172 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-016-2549-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-016-2549-9