Abstract

Projective content is heterogeneous, with classes of projective content differing in several properties (e.g., Potts 2005; Tonhauser et al. 2013). Recently, Tonhauser et al. (2018) found that projective content in English varies in its projectivity both between and within classes, and also that there is by-participant and by-lexical content projection variability. This paper shows that projection variability is not unique to English but also attested in Paraguayan Guaraní, a Tupí-Guaraní language that is genetically unrelated to and typologically different from English. This finding suggests that projection variability may be a cross-linguistically universal property of projective content. The comparison of English and Paraguayan Guaraní also reveals parallels in how projective the content associated with a translation pair is. This finding strengthens the empirical support for the position that some projective content is nondetachable (e.g., Levinson and Annamalai 1992; Simons 2001; Abrusán 2011, 2016; Tonhauser et al. 2013). The paper discusses implications for analyses of projective content, which differ in whether they lead us to expect projection variability and cross-linguistic similarities in projection variability. The paper also addresses methodological considerations in exploring projection variability in fieldwork-based research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Paraguayan Guaraní, which is spoken by about five million people in Paraguay, is a mildly polysynthetic, agglutinative and head-marking language with a split-S argument marking system. Word order is relatively free and influenced by information structure. For overviews of the grammar see, e.g., Gregores and Suárez (1967), Velázquez-Castillo (2004a) and Estigarribia (2017).

The colors were chosen to maximize accessibility for readers with color vision deficiencies. The full-color paper is available online.

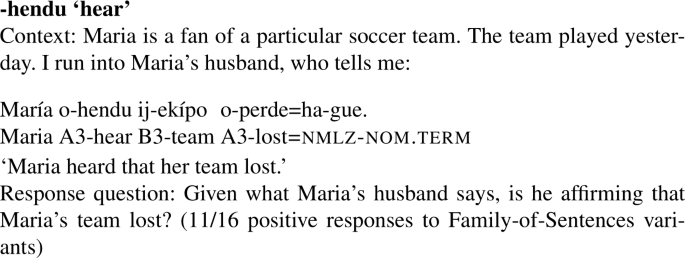

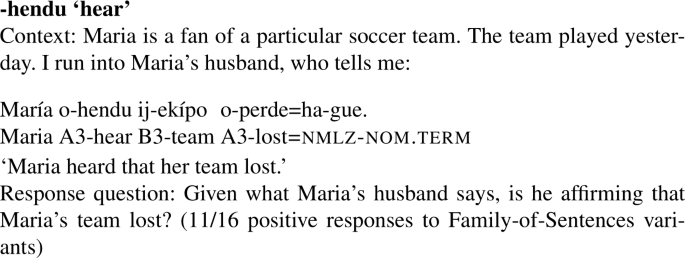

English see and hear are taken to be factive when the complement describes an event that can be seen or heard, respectively, and non-factive/evidential otherwise. The CCs of -hecha ‘see’ and -hendu ‘hear’ are assigned to different classes here because -hecha ‘see’ was combined with complements that described an event that can be seen whereas -hendu ‘hear’ was combined with complements that described an event that cannot be heard.

Paraguayan Guaraní examples are given in the standardized orthography of the language used in Paraguay (Velázquez-Castillo 2004b), except that all postpositions are suffixed to their host. Following this orthography, stressed oral syllables are marked with an acute accent and stressed nasal syllables are marked with a tilde; acute accents are not written for normally accented words, which have stress on the final syllable. I use glosses specified in the Leipzig Glossing Rules and the following additional glosses: A/B = set A/B cross-reference marker, ag = agentive, je = reflexive/passive marker, nom.term = nominal terminative aspect, nonag = non-agentive, pe = (in)direct object and locative marker, pron = pronoun, prosp = prospective aspect.

This quote has been altered slightly to match the spelling conventions and the terminology used in the current paper.

Some of the verbs that can take a clausal complement with =ha ‘nmlz’ can also take a clausal complement without. What governs the distribution of =ha ‘nmlz’ is a question for future research.

The native speakers of Paraguayan Guaraní that participated in the work reported in this paper were fluent in Paraguayan Guaraní and Spanish (on bilingualism in Paraguay see, e.g., von Gleich 1993; Fasoli-Wörmann 2002; Stewart 2017). The contexts and response questions were presented in Spanish. For discussions of considerations that go into which language to use in research on languages one does not speak natively see Matthewson 2004 and AnderBois and Henderson 2015.

I presented the native speaker with utterances of sentences describing 34 lexical contents and asked them to identify any that seem much more likely or unlikely than others. A couple of lexical contents were replaced based on this speaker’s feedback.

These recordings as well as the data and the R code for generating the figures and analyses presented in this paper are available at https://github.com/judith-tonhauser/guarani-variability.

A model with random slopes for expression by participant did not converge. A model that included the interaction of expression and block order was not significantly better than reported model, suggesting that the order in which participants completed the task did not influence their responses.

Projection variability can also be compared by investigating which expression/content pairs are statistically significantly different from one another across two languages. This avenue is not pursued here because the data collected in the pilot study in Sect. 2.2 were not subjected to statistical analysis and because of the difference in power between the experiment in Sect. 2.3 and the experiments in Tonhauser et al. 2018. Preliminary evidence for similarities in projection variability comes, however, from the observation that the contents associated with NRRCs and possessive noun phrases in both languages were more projective than the contents associated with the change-of-state expression/stop, =nte ‘only’/only and -juhu ‘discover’ / discover (though the latter was marginal in Paraguayan Guaraní for NRRCs).

Future research needs to determine what such differences are due to. One possibility is that such differences are due to the lexical contents of the items used in the experiment and in Tonhauser et al. (2018). Another possibility is that the truth conditional content and/or discourse use of -mombe’u ‘confess, tell’ and confess are different.

The correlation also holds for the 11 expression/content pairs coded as presuppositions, again regardless of whether the projection means come from the pilot (\(r_{\mathrm{s}}= .633\), n = 11, p = .036) or the experiment (\(r_{\mathrm{s}}= .624\), n = 11, p = .04).

References

Abrusán, Márta. 2011. Predicting the presuppositions of soft triggers. Linguistics and Philosophy 34: 491–535.

Abrusán, Márta. 2016. Presupposition cancellation: Explaining the ‘soft-hard’ trigger distinction. Natural Language Semantics 24: 165–202.

Abusch, Dorit. 2002. Lexical alternatives as a source of pragmatic presupposition. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 12, 1–19. Ithaca: CLC Publications.

Abusch, Dorit. 2010. Presupposition triggering from alternatives. Journal of Semantics 27: 37–80.

Anand, Pranav, and Valentine Hacquard. 2014. Factivity, belief and discourse. In The art and craft of semantics: A festschrift for Irene Heim, 69–90. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics.

AnderBois, Scott, and Robert Henderson. 2015. Linguistically established discourse context: Two case studies from Mayan languages. In Methodologies in semantic fieldwork, eds. Ryan Bochnak and Lisa Matthewson, 207–232. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

AnderBois, Scott, Adrian Brasoveanu, and Robert Henderson. 2015. At-issue proposals and appositive impositions in discourse. Journal of Semantics 32: 93–138.

Beaver, David, and Brady Clark. 2008. Sense and sensitivity: How focus determines meaning. Oxford: Wiley–Blackwell.

Beaver, David, and Emiel Krahmer. 2001. A partial account of presupposition projection. Journal of Logic, Language and Information 10: 147–182.

Bochnak, M. Ryan, and Lisa Matthewson, eds. 2015. Methodologies in semantic fieldwork. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. 2016. Praat: Doing phonetics by computer [computer program]. Version 6.0.19, retrieved 13 June 2016 from http://www.praat.org/.

Chemla, Emmanuel. 2009. An experimental approach to adverbial modification. In Semantics and pragmatics: From experiment to theory, eds. Uli Sauerland and Kasuko Yatsushiro. New York: Palgrave Macmillian.

Chierchia, Gennaro, and Sally McConnell-Ginet. 1990. Meaning and grammar. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Christensen, Rune Haubo Bojesen. 2013. “ordinal”: Regression models for ordinal data: R package. Version ordinal_2015.6-28.

Cohen, Jacob. 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. New Jersey: Erlbaum.

Estigarribia, Bruno. 2017. A grammar sketch of Paraguayan Guaraní. In Guaraní linguistics in the 21st century, eds. Bruno Estigarribia and Justin Pinta, 7–85. Leiden: Brill.

Fasoli-Wörmann, Daniela. 2002. Sprachkontakt und Sprachkonflikt in Paraguay. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Gregores, Emma, and Jorge A. Suárez. 1967. A Description of Colloquial Guaraní. The Hague: Mouton de Gruyter.

Grice, Paul. 1975. Logic and conversation. In Syntax and semantics 3: Speech acts, eds. Peter Cole and Jerry Morgan, 64–75. New York: Academic Press.

Gutzmann, Daniel. 2015. Use-conditional meaning: Studies in multidimensional semantics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heim, Irene. 1983. On the projection problem for presuppositions. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 2, eds. Michael Barlow, Dan Flickinger, and Michael Westcoat, 114–125.

Horn, Laurence R. 2002. Assertoric inertia and NPI licencing. In 38th annual meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS): Parasession on negation and polarity, Vol. 38, 55–82.

Horn, Lawrence R. 1996. Exclusive company: Only and the dynamics of vertical inference. Journal of Semantics 13: 1–40.

Hothorn, Torsten, Frank Bretz, and Peter Westfall. 2008. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biometrical Journal 50 (3): 346–363.

Kadmon, Nirit. 2001. Formal pragmatics. Oxford: Blackwell.

Karttunen, Lauri. 1971. Some observations on factivity. Papers in Linguistics 4: 55–69.

Levinson, Stephen C., and E. Annamalai. 1992. Why presuppositions aren’t conventional. In Language and text: Studies in honour of Ashok R. Kelkar, ed. Ravindranatha Srivastava, 227–242. Delhi: Kalinga Publications.

Matthewson, Lisa. 2004. On the methodology of semantic fieldwork. International Journal of American Linguistics 70: 369–415.

Murray, Sarah. 2014. Varieties of update. Semantics & Pragmatics 7 (2): 1–53.

Potts, Chris. 2007. The expressive dimension. Theoretical Linguistics 33: 165–197.

Potts, Christopher. 2005. The logic of conventional implicatures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

R Core Team. 2016. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: Austria R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

Roberts, Craige. 2011. Only: A case study in projective meaning. In Formal semantics and pragmatics: Discourse, context, and models, the Baltic international yearbook of cognition, logic and communication, eds. Barbara Partee, Michael Glanzberg, and Jurgis Skilters, Vol. 6. Kansas: New Prarie Press.

Romoli, Jacopo. 2015. The presuppositions of soft triggers are obligatory scalar implicatures. Journal of Semantics 32: 173–291.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2010. Local contexts and local meanings. Philosophical Studies 151: 115–142.

Simons, Mandy. 2001. On the conversational basis of some presuppositions. In Semantics and Linguistics Theory (SALT) 11, 431–448. Ithaca: CLC Publications.

Simons, Mandy, David Beaver, Craige Roberts, and Judith Tonhauser. 2017. The best question: Explaining the projection behavior of factive verbs. Discourse Processes 3: 187–206.

Smith, E. Allyn, and Kathleen Currie Hall. 2011. Projection diversity: Experimental evidence. In 2011 ESSLLI Workshop on Projective Content, 156–170.

Spector, Benjamin, and Paul Egré. 2015. A uniform semantics for embedding interrogatives: An answer, not necessarily the answer. Synthese 192: 1729–1784.

Stewart, Andrew. 2017. Jopara and the Spanish-Guarani language continuum in Paraguay: Considerations in linguistics, education, and literature. In Guaraní linguistics in the 21st century, eds. Bruno Estigarribia and Justin Pinta, 379–416. Leiden: Brill.

Tonhauser, Judith, David Beaver, and Judith Degen. 2018. How projective is projective content? Gradience in projectivity and at-issueness. Journal of Semantics 35: 495–542.

Tonhauser, Judith, David Beaver, Craige Roberts, and Mandy Simons. 2013. Toward a taxonomy of projective content. Language 89: 66–109.

Tonhauser, Judith, Marie-Catherine de Marneffe, Shari R. Speer, and Jon Stevens. 2019. On the information structure sensitivity of projective content. In Sinn und Bedeutung 23, eds. M. Terea Espinal et al., Vol. 2, 365–391. Bellaterra: Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona.

van der Sandt, Rob. 1992. Presupposition projection as anaphora resolution. Journal of Semantics 9: 333–377.

Velázquez-Castillo, Maura. 2004a. Guaraní (Tupí-Guaraní). In Morphology: An international handbook on inflection and word-formation, eds. Geert E. Booij, Christian Lehmann, Joachim Mugdan, and Stavros Skopeteas, Vol. 2, 1421–1432. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Velázquez-Castillo, Maura. 2004b. Serial verb constructions in Paraguayan Guaraní. International Journal of American Linguistics 70 (2): 187–213.

von Gleich, Utta. 1993. Paraguay – Musterland der Zweisprachigkeit? Quo vadis Romania 1: 19–30.

Xue, Jingyang, and Edgar Onea. 2011. Correlation between projective meaning and at-issueness: An empirical study. In 2011 ESSLLI workshop on projective content, 171–184.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the native speakers of Paraguayan Guaraní who worked with me on this project, including Ansia Sabina Maciel de Cantero, Evelin Leonor Jara Cespedes, Jeremias Ezequiel Sanabria O., Marité Maldonado, Perla Valdéz de Ferreira, Ricardo Aranda Locio, Robert Ariel Barreto Villalba and Vicky Barreto. For helpful comments on the work reported on here, I thank Judith Degen, Amy Rose Deal, the anonymous reviewers for Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, as well as audiences at the University of California in Los Angeles and in San Diego, and at the 2019 Experimental Pragmatics conference in Edinburgh. Finally, I gratefully acknowledge research support from the National Science Foundation grants BCS-0952571 and BCS-1452674.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

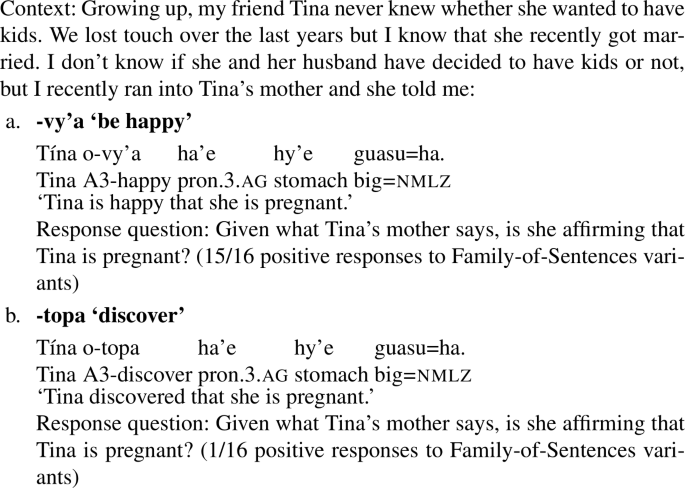

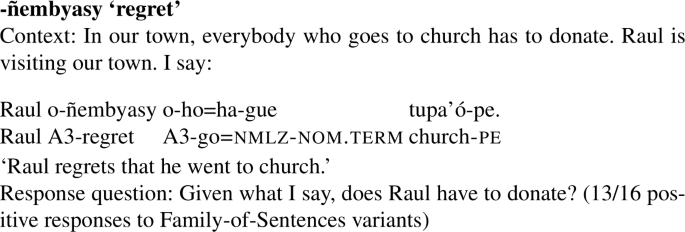

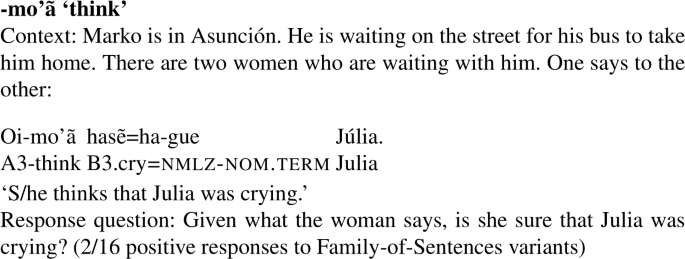

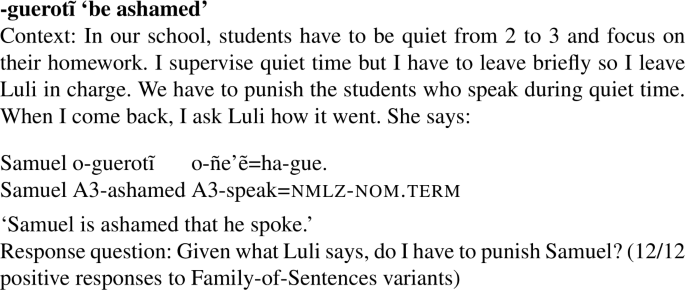

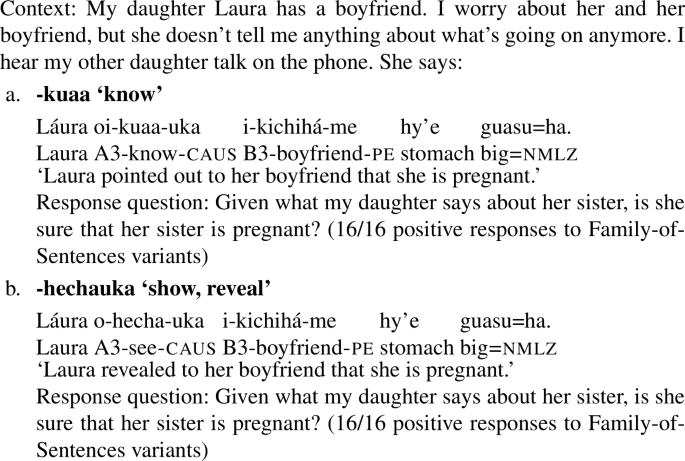

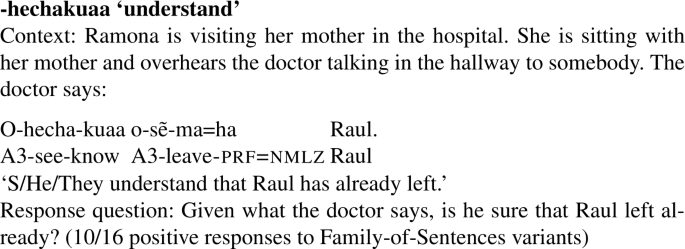

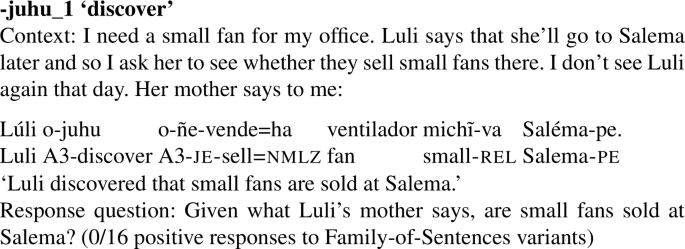

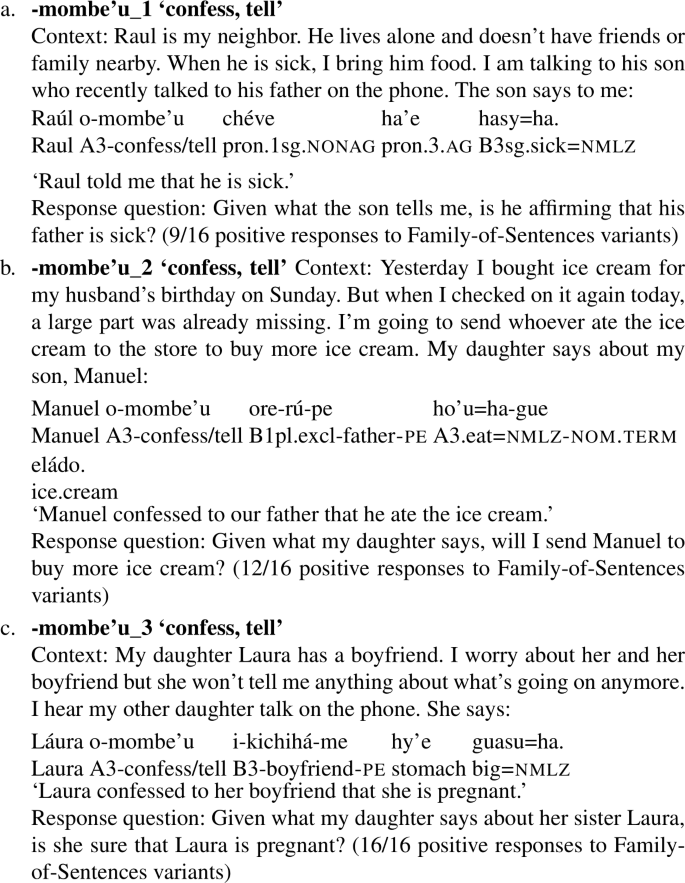

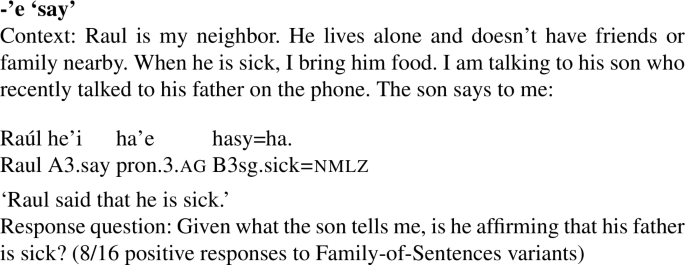

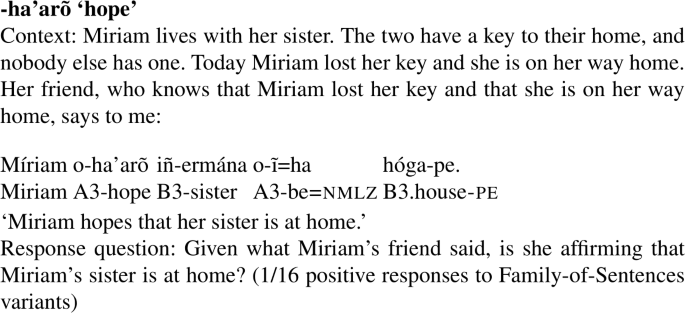

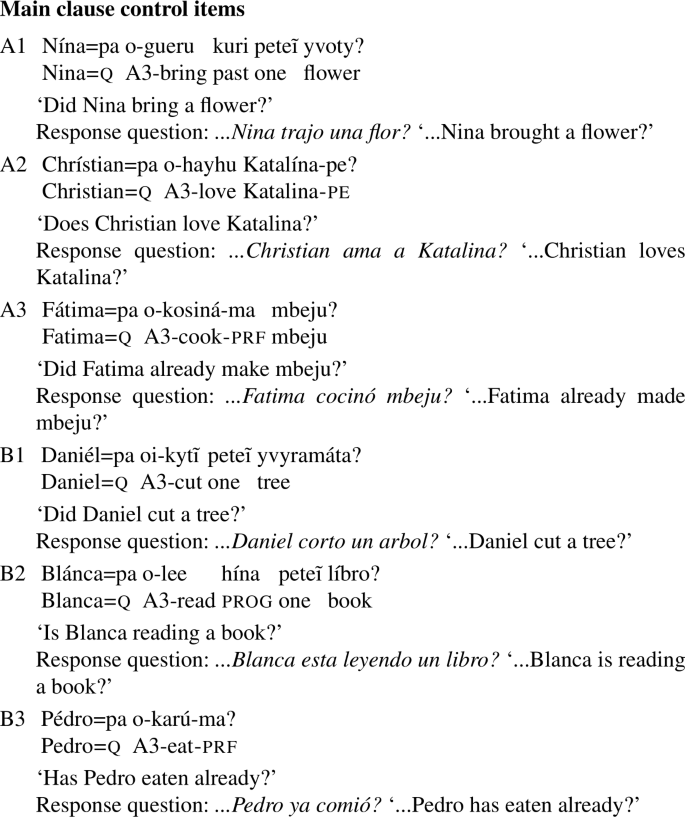

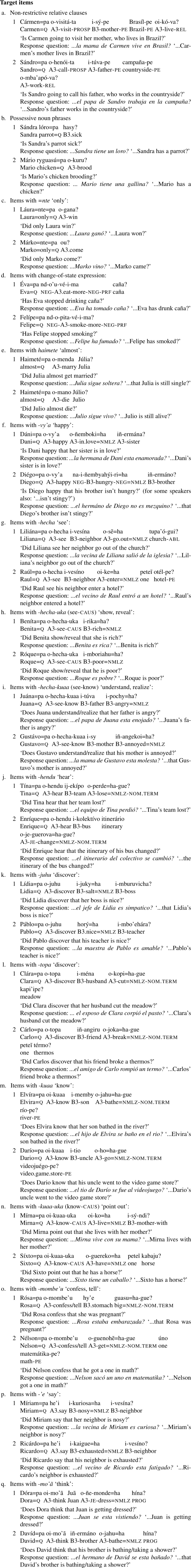

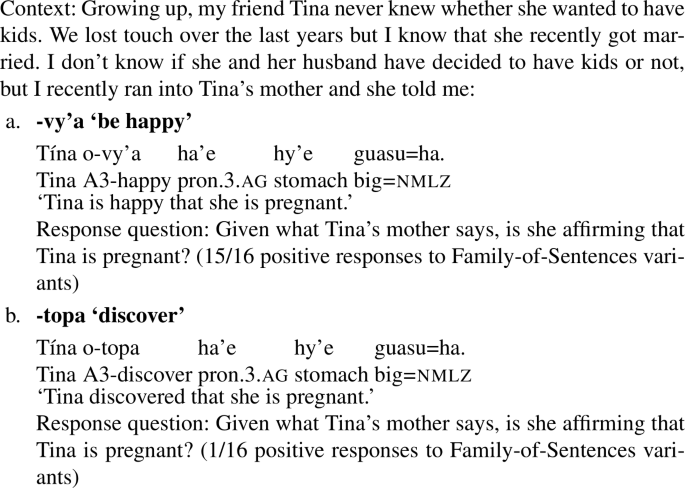

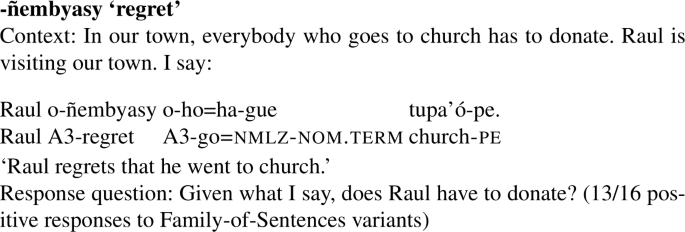

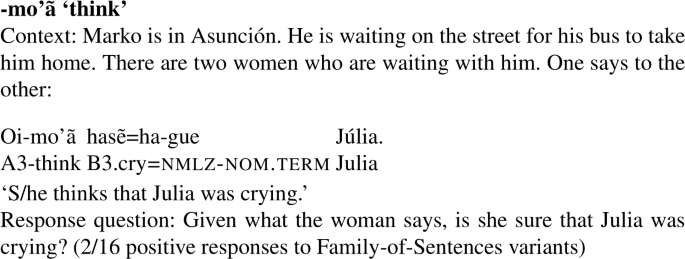

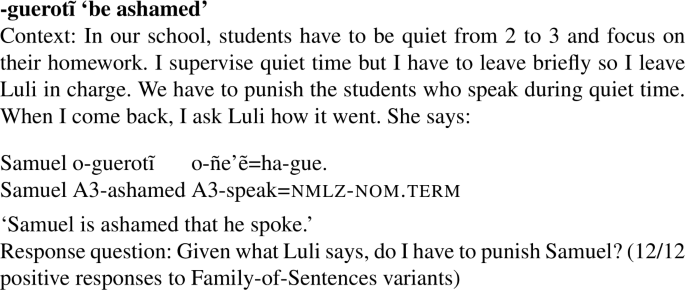

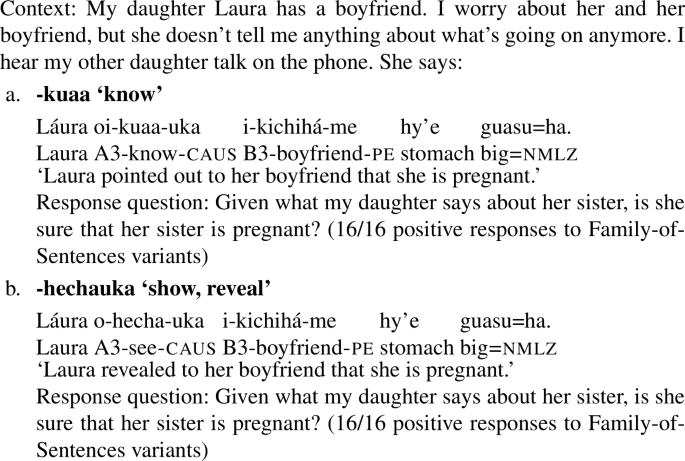

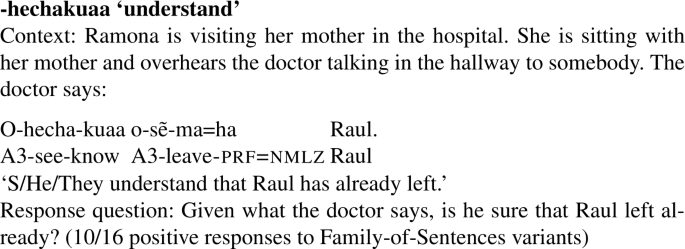

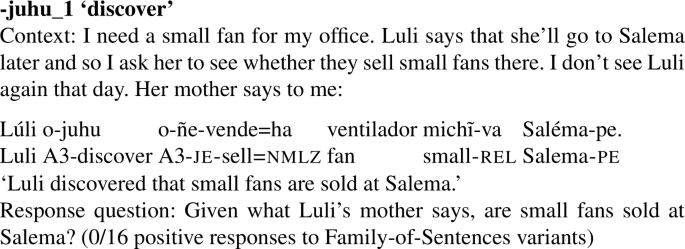

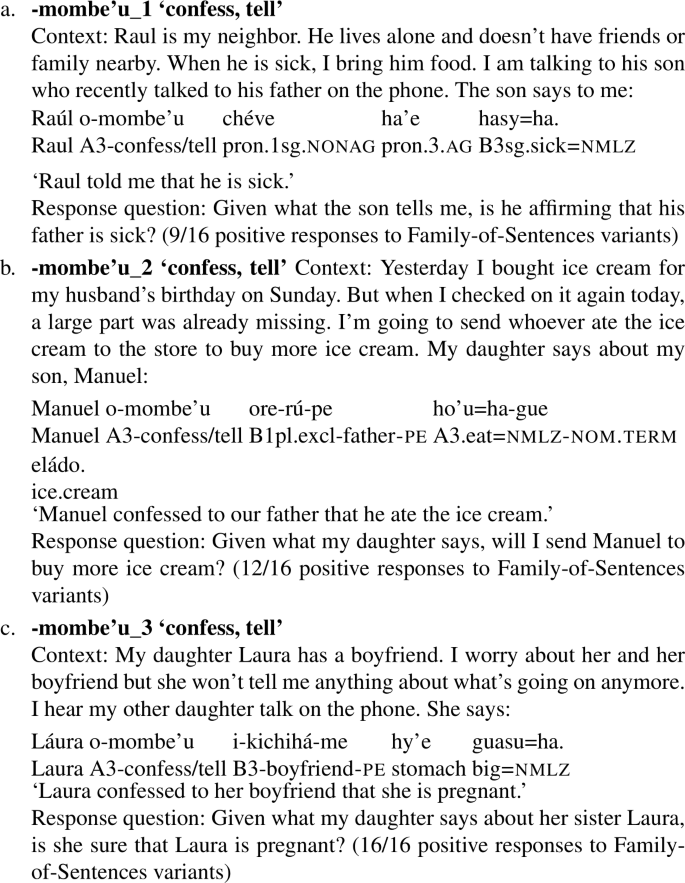

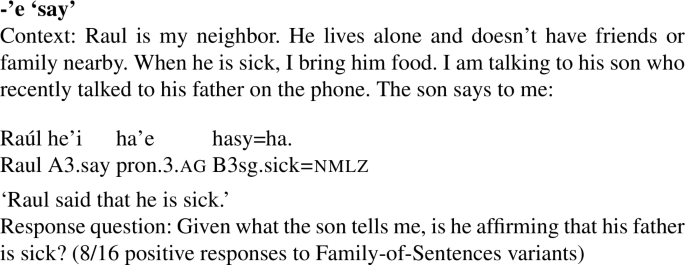

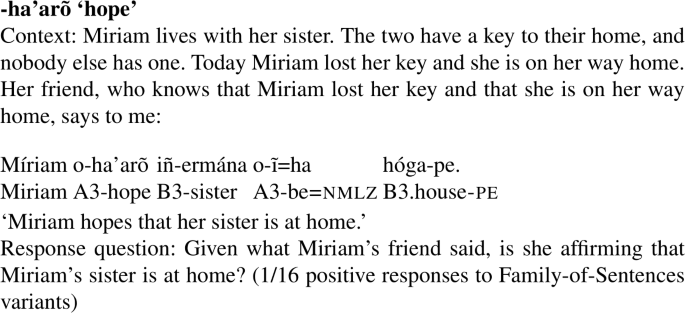

Appendix A: Examples used in one-on-one elicitation

This appendix provides the unembedded sentences from which the Family-of-Sentences variants were formed for the investigation described in Sect. 2.1 as well as the English translations of the response questions in the direct and indirect implication response tasks that the participants were asked. Only the examples not yet discussed in Sect. 2.1 are given.

-

(15)

-

(16)

-

(17)

-

(18)

-

(19)

-

(20)

-

(21)

-

(22)

-

(23)

-

(24)

-

(25)

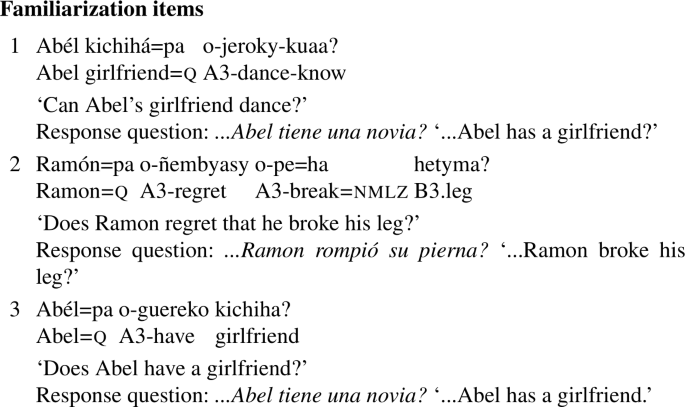

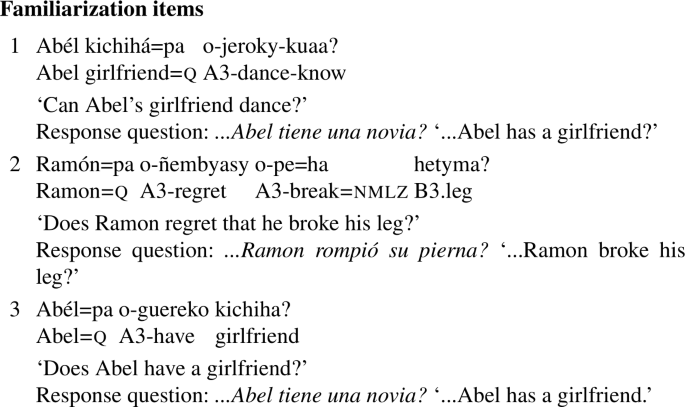

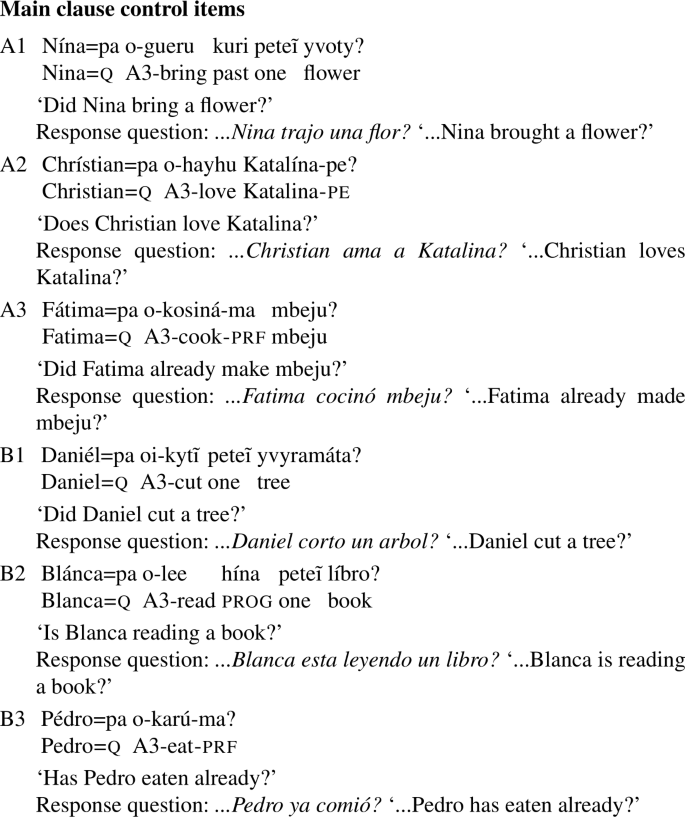

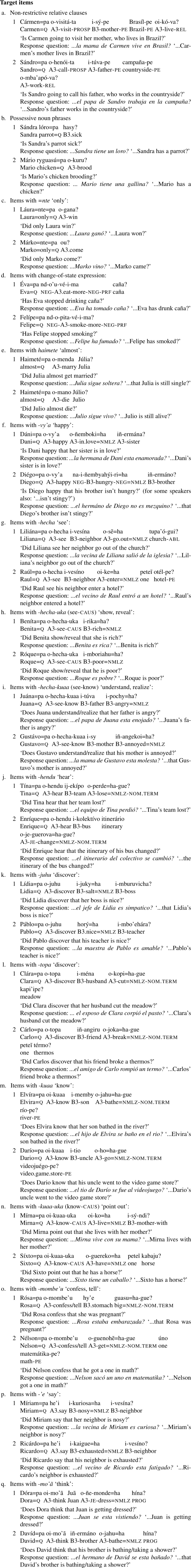

Appendix B: Experiment stimuli

The experiment stimuli were recordings of the sentences in (26) to (28). The recordings can be found in the GitHub repository mentioned in fn. 9. Each example also identifies the content whose projectivity was explored by providing the clausal complement of the response question Según lo que preguntó Magda, que certeza tiene de que...? ‘According to what Magda asked, is she certain that...?’.

-

(26)

-

(27)

-

(28)

Appendix C: Experiment blocks A and B

Table A.1 shows the order of the items in blocks A and B in the experiment reported on in Sect. 2.3. The items are identified by the labels in (26) to (28) above.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tonhauser, J. Projection variability in Paraguayan Guaraní. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 38, 1263–1302 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-019-09462-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-019-09462-x