Abstract

This paper is a study of 55 ditransitive idioms in Hebrew, to the best of our knowledge, the first of its kind. The examination of these idiomatic constructions reveals asymmetries in their composition, thereby providing us with new insights into their internal structure and the principles governing their formation. In particular, we show that idioms reflect properties of their literal counterparts, explain word order patterns ditransitive idioms exhibit, argue that idioms do not have to be continuous constituents, and investigate the distribution of their free position. In addition, the paper provides support for Rappaport Hovav and Levin’s (2008) “verb sensitive” approach to the dative alternation and Landau’s (1994) seminal observation that Hebrew manifests the alternation, though it fails to mark it morphologically.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The context of relative clauses is often used in order to examine whether a verb governs le- or el. The reason for this is that in main clauses both pronominal le- and el cannot refer to inanimates (Francez 2006).

Francez (2006) refers to verbs encoding a Caused Motion meaning as verbs encoding a Caused Change of Location meaning. Both terms are used in the literature.

15 native Hebrew speakers were consulted when in doubt (as will be detailed in fns. 8–10). In addition, speakers were informally consulted regarding the admissibility of argument order alternation for all idioms.

These are cases subject to a manipulation of information structure that gives rise to a literal interpretation. Thus, the Goal-Theme order in (10b), for instance, involves focus on the Goal and loses the idiomatic meaning.

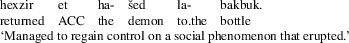

An anonymous reviewer mentions Google examples such as (i) and (ii) as counterexamples to (10b) and (12b) respectively. All online examples accessed 14 October 2016.

-

(i)

-

(ii)

To check the status of such examples we composed a questionnaire comprising (ia), (ib), (ii) and 17 fillers, asking speakers to rate the sentences as good/natural, not good/unnatural, or ‘in between’. The questionnaire was filled in by 15 speakers. Examples (ia) and (ii) were judged by 14 speakers as not good/unnatural; one speaker rated (1a) as ‘in between’, and one speaker judged (ii) as good/natural. Example (ib) was judged by 12 speakers as not good/unnatural, by two speakers as good, and by one speaker as ‘in between’. We believe that (ib) includes a Theme heavier than normally in the idiom, which allows it to undergo Heavy NP-shift; (ia) involves focus on ‘add to the fire’ marked by rak (‘only’), and in (iii) argument order was manipulated to allow the ‘medicine’ to be adjacent to its apposition ‘to initiate artificial selling’. For most speakers such manipulations sound unnatural.

-

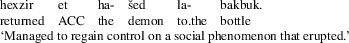

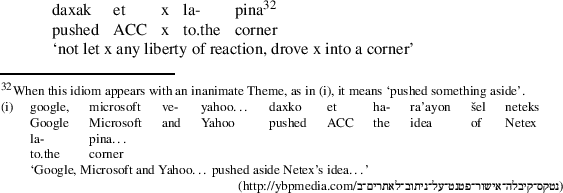

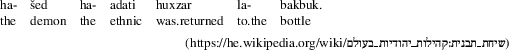

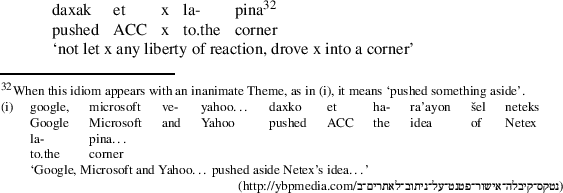

(i)

Sentence (13b) is marked by */?? because 4 native speakers out of 15 reported that they could get the idiomatic meaning even in this Goal-Theme order, but would not use it in this specific word order. Google searches did not find instances of (13b) in Goal-Theme order, except for instances manipulated by Heavy NP-Shift, as in (i) and (ii) (also mentioned by an anonymous reviewer). The heavy Theme appears in brackets. (The meaning of the idiom changes depending on whether or not the Theme is animate ((i) vs. (ii)), as mentioned in fn. 32.)

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(i)

Occasionally, idiom dictionaries do not specify the free Goal.

Reviewers raised two potential types of counterexamples to the restriction in (22). One type involves examples with verbs such as cause and permit, as illustrated in (i, ii).

-

(i)

I caused the cat to get out of the bag.

-

(ii)

…but as a rule custom was too strong to permit the ice to be broken. (Colquhoun 1902:29)

These verbs, however, do occur in ECM constructions, as illustrated in (iii, iv) (thanks to Louise McNally for providing (iv)).

-

(iii)

I caused there to be total silence. (McCawley 1988, p. 70 (12a))

-

(iv)

The trademark law permits there to be both an American insurance Company and an American Airlines as well as… (Hall 2002:663)

The second type of counterexample involves relative clauses whose head is part of the fixed material of an idiom occurring within the relative clause, as in (v).

-

(v)

He knew of the boy from the tabs they kept on the Slayer and her group. (http://www.tthfanfic.org/Story-28812/cloudleonsgurl+Don+t+You+Hurt+My+Girl.htm)

The availability of idiomatic interpretation in cases such as (v) has been discussed in the literature together with other phenomena requiring the interpretation of the head of the relative within the relative clause (low interpretation), e.g., anaphor binding, the availability of de dicto reading etc. These phenomena are known as reconstruction effects. The raising analysis of relative clauses straightforwardly explains the effects. Under the raising analysis, the relative clause is the CP-complement of D, and the head of the relative clause originates within the relative and raises to its SpecCP, as schematized in (vi) (see Bianchi 1999; Bhatt 2002; Sichel 2014, and references therein for more discussion). Under the raising analysis, kept tabs in (v) is expected to have its idiomatic interpretation because tabs receives its semantic role idiom internally, as shown in (vi).

-

(vi)

…[DP the [CP tabsi [ they kept t i on…]]].

-

(i)

Given Nunberg et al. (1994) claim that non-decomposable idioms allow neither raising nor passivization, one could suggest that the irrelevance of decomposability for argument word order in ditransitive idioms constitutes evidence that the dative alternation does not result from movement, as movement would be blocked in non-decomposable idioms. We will not pursue the matter any further here. We note nonetheless that among our non-decomposable idioms, there are idioms that do allow passive movement (e.g., (i, ii)). See also Punske and Stone (2014) for discussion of the passivizability of idioms.

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(i)

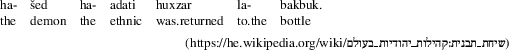

Three apparent counterexamples to generalization (25b) are discussed at the end of this subsection.

The sentence is grammatical only if the Goal argument (London) is interpreted metonymically as an institution, such as the London office, which can allow a Recipient/Possessor interpretation.

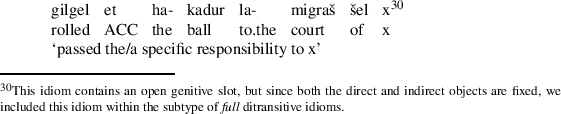

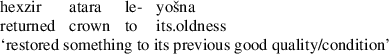

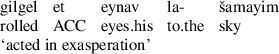

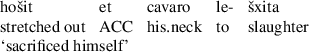

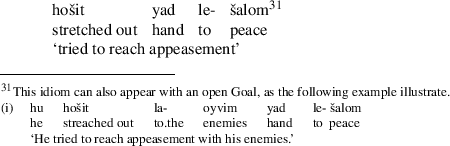

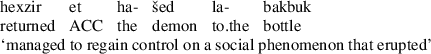

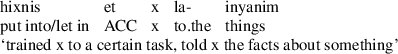

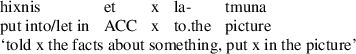

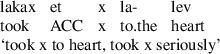

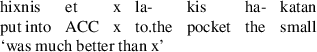

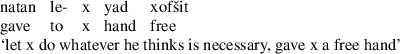

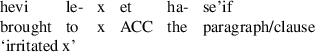

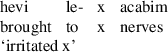

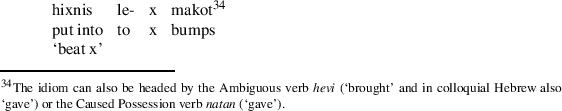

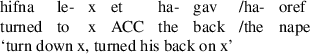

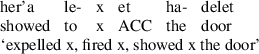

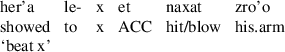

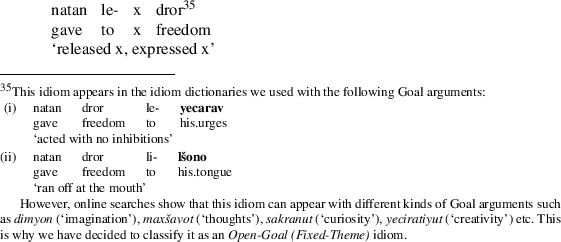

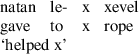

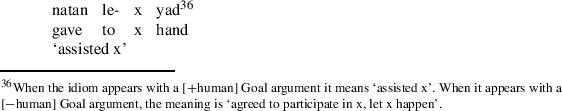

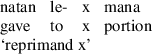

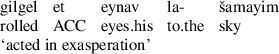

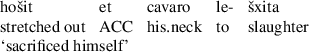

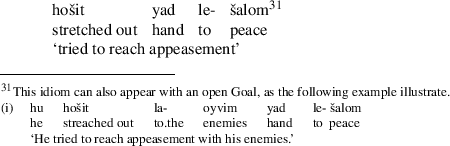

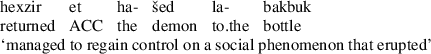

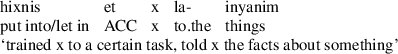

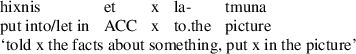

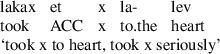

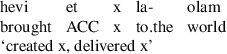

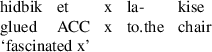

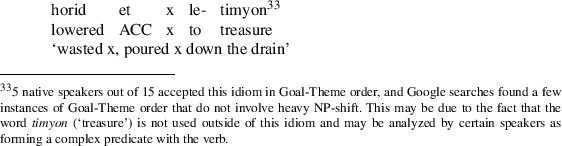

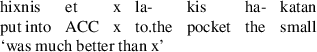

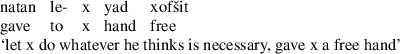

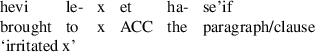

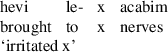

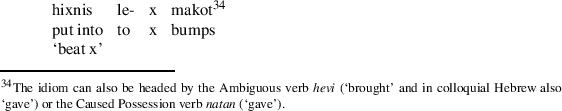

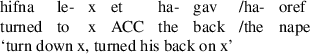

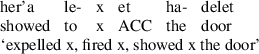

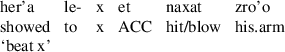

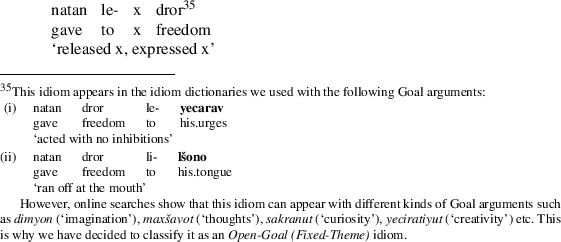

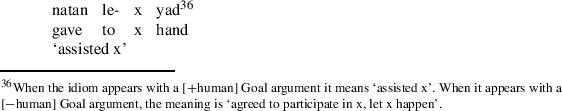

There are two apparent counterexamples to generalization (35b). The idioms in (i) and (ii), which are Open-Goal (Fixed-Theme) idioms, are headed by the Caused Motion verbs hixnis (‘put into/let in’) and hifna (‘turn to’), respectively. On a second glance, however, it becomes clear that hixnis (‘put into’) and hifna (‘turned to’) in (i) and (ii) respectively denote a Caused Possession meaning. That is, the verbs have undergone semantic drift under the metaphoric transfer. This claim is supported by the fact that they use the pronominal le (iii, iv), which Caused Motion verbs disallow. Further, hixnis (‘put into’) in (i) can be replaced by the Caused Possession verb natan (‘gave’) and the Ambiguous verb hevi (‘brought’ and in colloquial Hebrew also ‘gave’).

-

(i)

hixnis/

natan/

hevi

le-

x

makot

put into

gave/

brought

to

x

blows

‘beat x’

-

(ii)

hifna

le-x

et

ha-

gav/

oref

turned

to x

ACC

the

back/

nape

‘turned his back on x’

-

(iii)

ha-iš

še-

ha-

ganav

hixnis

lo

makot…

the man

that

the

thief

put into

to.him

blows

‘the man that the thief hit…’

-

(iv)

ha-

iš

še-

kulam

hifnu

lo

et

ha- gav…

the

man

that

everybody

turned

to.him

ACC

the back

‘the man who everybody turned their back on…’

The idiom in (ii) has an additional instantiation, in which the verb does have a Caused Motion meaning, as will be illustrated in (42), (43) and discussed thereafter.

-

(i)

There are also isolated instances of Open-Goal (Fixed-Theme) idioms headed by a Caused Possession verb involving a [−human] Goal capable of possession, e.g., idioms (48) and (50) in the Appendix. This is also expected if (37) is a tendency, not an absolute principle.

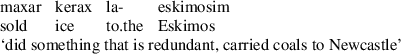

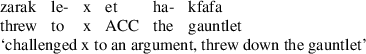

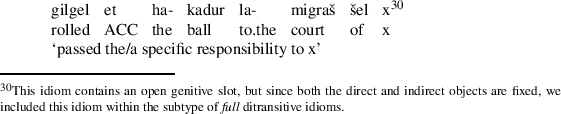

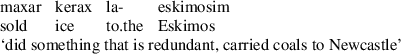

Bruening (2010:536, fn. 14) mentions only two examples of full ditransitive idioms in English: give the devil/him his due (‘acknowledge the positive qualities of a person who is unpleasant’) and send/carry coals to Newcastle (‘do something redundant’), suspecting they may be partial idioms owing to the substitutability of one of their constituents.

As discussed in Sect. 2.2, an idiom is considered decomposable if it is isomorphic with its meaning, in the sense that each of its constituents corresponds to an element of its meaning. A non-decomposable idiom is not isomorphic with its meaning; that is, its idiomatic interpretation cannot be mapped onto the different constituents of the idiom. Idioms that exhibit only partial mapping between constituents and meaning are not considered decomposable here. As far as the internal arguments are concerned, we require matching in neither categorial status nor internal structure, between idiom and meaning. Despite these guidelines, classifying idioms into decomposable and non-decomposable is not always straightforward. Nonetheless, we believe the picture emerging here motivates the conclusion that the decomposability property is irrelevant to the choice of linear order of internal arguments in Goal-ditransitive idioms. Finally, often, in addition to the translation of the Hebrew idiom, we also mention the parallel English idiom. The property of decomposability should of course not be checked against the English idiom.

References

Barss, Andrew, and Howard Lasnik. 1986. A note on anaphora and double objects. Linguistic Inquiry 17: 347–354.

Berman, Ruth. 1982. On the nature of ‘oblique’ objects in bitransitive constructions. Lingua 56: 101–125.

Bhatt, Rajesh. 2002. The raising analysis of relative clauses: Evidence from adjectival modification. Natural Language Semantics 10: 43–90.

Bianchi, Valentina. 1999. Consequences of antisymmetry: Headed relative clauses. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Botwinik-Rotem, Irena. 2003. The thematic and syntactic status of Ps: The dative, directional, locative distinction. In Research in Afroasiatic grammar II, ed. Jacqueline Lecarme, 79–105. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Botwinik-Rotem, Irena. 2004. The category P: Features, projections, interpretation. PhD dissertation. Tel Aviv University.

Bresnan, Joan. 1982. Control and complementation. Linguistic Inquiry 13: 343–434.

Bresnan, Joan, Anna Cueni, Tatiana Nikitina, and R. Harald Baayen. 2007. Predicting the dative alternation. In Cognitive foundations of interpretation, eds. Gerlof Boume, Irene Kraemer, and Joost Zwarts, 69–94. Amsterdam: Royal Netherlands Academy of Science.

Bruening, Benjamin. 2010. Ditransitive asymmetries and a theory of idiom formation. Linguistic Inquiry 41(4): 519–562.

Cecchetto, Carlo, and Caterina Donati. 2015. ‘Quattro passi’ in the NP structure. Talk given at the 8th Brussels conference on generative linguistics: The grammar of idioms. CRISSP, Brussels.

Chomsky, Noam. 1980. Rules and representations. New York: Columbia University Press.

Cohen, Tuvya. 1999. nivon ivri xadaš [New anthology of sayings in Hebrew]. Tel Aviv: Yavneh Publishing House.

Colquhoun, Ethel. 1902. Two on their travels. London: Heineman. Available at https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=2ssvAAAAYAAJ. Accessed 24 October 2016.

Emonds, Joseph. 1972. Evidence that indirect object movement is a structure-preserving rule. Foundations of Language 8: 546–561.

Francez, Itamar. 2006. Possessors, goals and the classification of ditransitive predicates: Evidence from Hebrew. In Empirical issues in syntax and semantics 6: papers from CSSP 2005, eds. Olivier Bonami and Patricia Cabredo Hofherr, 137–154. Paris: Colloque de Syntaxe et Sémantique à Paris.

Fruchman, Maya, Orna Ben-Nathan, and Niva Shani. 2001. nivon ariel [Ariel dictionary of idioms]. Kiryat Gat: Korim Publishing House.

Green, Georgia M. 1974. Semantics and syntactic regularity. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Hall, Kermit. 2002. The Oxford companion to American law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harley, Heidi. 2002. Possession and the double object construction. Linguistic Variation Yearbook 2: 29–68.

Horvath, Julia, and Tal Siloni. 2014. Idioms: The type sensitive storage model. Talk given at the TAU-GU workshop on relative clauses. Goethe Universität, Frankfurt.

Horvath, Julia, and Tal Siloni. 2016. The thematic phase and the architecture of grammar. In Concepts, syntax and their interface, eds. Martin Everaert, Marijana Marelj, and Eric Reuland, 129–174. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kim, Lan. 2012. An asymmetric theory of Korean ditransitives: Evidence from idioms. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 18(1): Article 16.

Kiparsky, Paul. 1987. Morphology and grammatical relations. Ms., Stanford University.

Landau, Idan. 1994. Dative shift and extended VP-shell. MA thesis, Tel Aviv University.

Larson, Richard. 1988. On the double object construction. Linguistic Inquiry 19: 335–391.

Larson, Richard. 1990. Double objects revised: A reply to Jackendoff. Linguistic Inquiry 21: 589–632.

Levanon, Moshe. 1989–1990. lexicon ivri le-nivim ve-le-matbe’ot lašon [Hebrew lexicon of sayings and idiomatic phrases]. Jerusalem: Zach and Co. Publishing House.

Marantz, Alec. 1984. On the nature of grammatical relations. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Marantz, Alec. 1993. Implications of asymmetries in double object constructions. In Theoretical aspects of Bantu grammar, ed. Sam A. Mchombo, 113–150. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Markovich, Nimrod. 2012. The nature of the open slot in Hebrew phrasal idioms. Seminar paper, Tel Aviv University.

McCawley, James D. 1988. The syntactic phenomena of English, Vol. 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Napoli, Diana. 1992. The double object construction, domain asymmetries and linear precedence. Linguistics 30: 837–871.

Nunberg, Geoffrey, Ivan A. Sag, and Thomas Wasow. 1994. Idioms. Language 70(3): 491–538.

Oehrle, Richard. 1976. The grammatical status of the English dative alternation. PhD dissertation, MIT.

O’Grady, William. 1998. The syntax of idioms. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 16(2): 279–312.

Pinker, Steven. 1989. Learnability and cognition: The acquisition of argument structure. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Punske, Jeffrey, and Megan Stone. 2014. Idiomatic expressions, passivization, and gerundization. Paper presented at the 2014 Linguistic Society of America (LSA) annual meeting.

Rappaport Hovav, Malka, and Beth Levin. 2008. The English dative alternation: The case for verb sensitivity. Journal of Linguistics 44: 129–167.

Richards, Norvin. 2001. An idiomatic argument for lexical decomposition. Linguistic Inquiry 32(1): 183–192.

Rosenthal, Rubik. 2005. milon ha-cerufim [Dictionary of Hebrew idioms and phrases]. Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House.

Sichel, Ivy. 2014. Resumptive pronouns and competition. Linguistic Inquiry 45(4): 655–693.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Grant No 2009269 from the United States-Israel Binational Science Foundation (BSF). For helpful comments and discussions, we are grateful to Julia Horvath, Irena Botwinik, Shir Givoni, Dganit Jenia Kim, and Dana Idan. We also thank five anonymous NLLT reviewers and Louise McNally for their useful remarks. Finally, thanks to the audiences at the Tel Aviv University Interdisciplinary Colloquium (February 2012, Israel), and at the Workshop on Relative Clauses and Idioms (November 2014, Goethe University, Frankfurt, Germany), where parts of this work have been presented.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

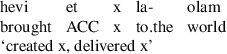

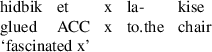

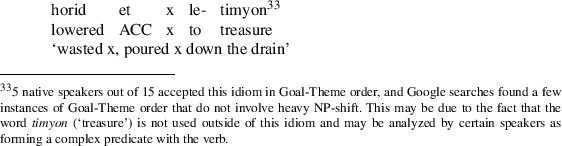

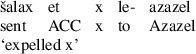

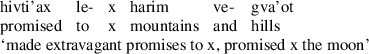

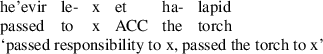

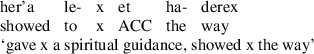

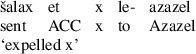

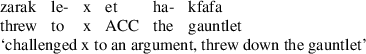

Appendix: Ditransitive idioms in Hebrew

Appendix: Ditransitive idioms in Hebrew

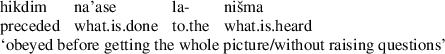

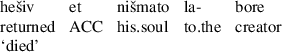

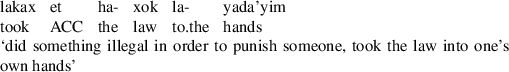

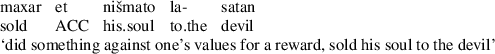

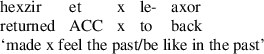

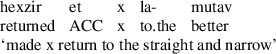

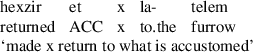

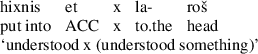

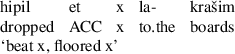

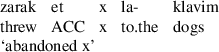

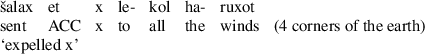

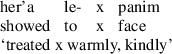

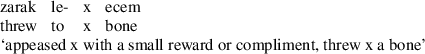

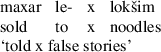

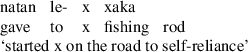

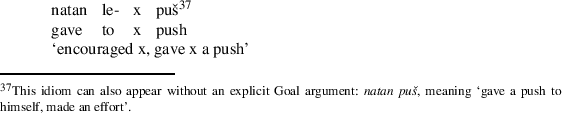

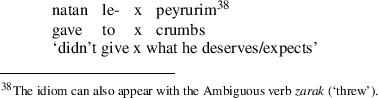

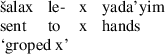

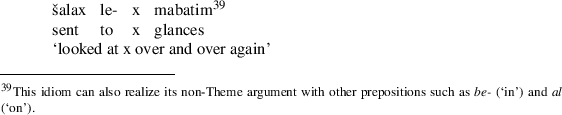

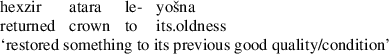

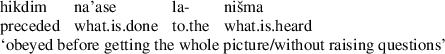

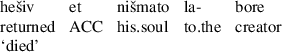

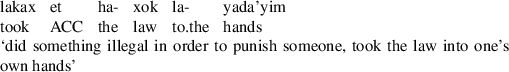

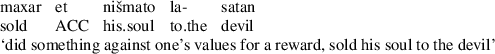

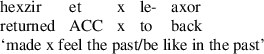

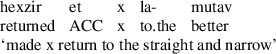

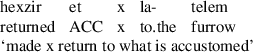

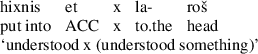

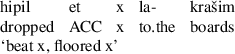

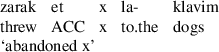

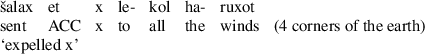

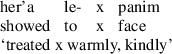

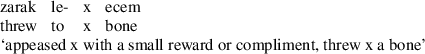

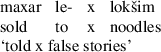

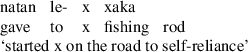

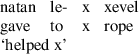

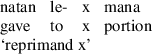

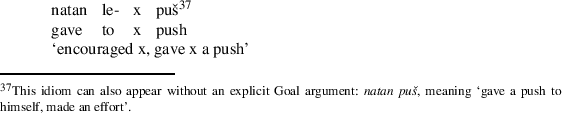

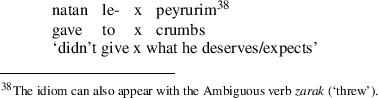

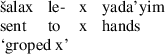

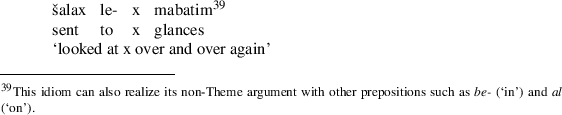

All idioms collected for this study are listed below in Hebrew alphabetical order. The argument order in which they appear here is the same as listed in idiom dictionaries. The idioms of each type are also divided into decomposable and non-decomposable idioms.Footnote 18

- 1. :

-

Full ditransitive idioms

-

1.1

Decomposable idioms

-

1.1

-

(1)

-

(2)

-

(3)

-

(4)

-

(5)

-

(6)

-

(7)

-

1.2

Non-decomposable idioms

-

(8)

-

(9)

-

(10)

-

(11)

-

(12)

-

(13)

-

(14)

-

(15)

-

(16)

- 2. :

-

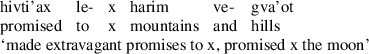

Fixed - Goal ( Open - Theme ) ditransitive idioms

-

2.1

Decomposable idioms

-

2.1

-

(17)

-

(18)

-

(19)

-

(20)

-

(21)

-

(22)

-

2.2

Non-decomposable idioms

-

(23)

-

(24)

-

(25)

-

(26)

-

(27)

-

(28)

-

(29)

-

(30)

-

(31)

-

(32)

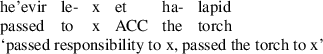

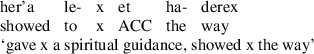

- 3. :

-

Open Goal (Fixed - Theme) ditransitive idioms

-

3.1

Decomposable idioms

-

3.1

-

(33)

-

(34)

-

(35)

-

(36)

-

(37)

-

(38)

-

(39)

-

(40)

-

3.2

Non-decomposable idioms

-

(41)

-

(42)

-

(43)

-

(44)

-

(45)

-

(46)

-

(47)

-

(48)

-

(49)

-

(50)

-

(51)

-

(52)

-

(53)

-

(54)

-

(55)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mishani-Uval, Y., Siloni, T. Ditransitive idioms in Hebrew. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 35, 715–749 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-016-9354-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-016-9354-8