Abstract

The notion of comparison class has figured prominently in recent analyses of the gradability properties of adjectives. We assume that the comparison class is introduced by the degree morphology of the adjective and present a new proposal where comparison classes are crucial to explain the distribution of adjectives in Spanish copular sentences headed by the verbs ser ‘beSER’ and estar ‘beESTAR’. The copula estar ‘be estar ’ appears whenever a gradable adjective merges with a within-individual comparison class, a modifier expressing a property of stages. The copular verb ser ‘be ser ’ appears when a gradable adjective merges with a between-individuals comparison class, a modifier expressing a property of individuals. The distinction between relative and absolute adjectives can be reduced to the semantic properties of the modifier expressing the comparison class that is merged in the functional structure of the adjective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In Kubota (2015) comparison class is the crucial notion to account for the ‘manner reading’ vs. the ‘surface-subject oriented reading’ of adverbs like stupidly, cleverly.

Though the ser/estar alternation also exists in other Romance languages, we will restrict ourselves to Spanish data in this paper. Moreover, there is dialectal variation in Spanish regarding the combination of adjectives with the copulas ser/estar, which will likewise not be dealt with in this paper. The data described correspond to the dialect of Castilian Spanish spoken in Madrid, Spain.

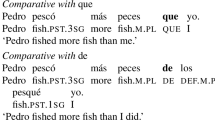

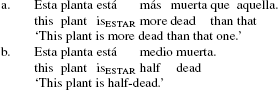

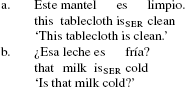

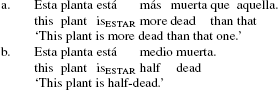

Notice that some of these adjectives (e.g. muerto ‘dead’) have been argued to be non-gradable (Syrett 2007). Since adjectives like these appear in comparative constructions and can be modified by proportional modifiers like medio ‘half’, we consider them gradable, in the line of Kennedy and McNally (2005):

-

(i)

-

(i)

In Fults (2006:157) a neo-Davidsonian approach to gradability is proposed in which the measuring function is removed from the adjective meaning and assigned to the degree morpheme.

See Anderson and Morzycki (2015) for a different semantics of degrees.

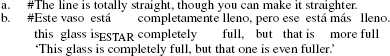

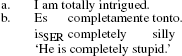

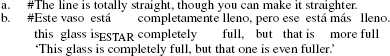

Combination with degree modifiers must be handled with care as a diagnostic of scalar structure. As Kennedy and McNally (2005) show, maximizers have an additional use in which they are roughly synonymous with very, (i). The true maximality use is distinguished because it entails that the end of a scale has been reached. Therefore, the examples in (ii) express contradictions, but the examples in (iii) are not contradictory (English examples from Kennedy and McNally 2005).

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(iii)

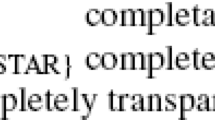

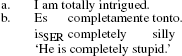

Similarly, a degree modifier like completamente is compatible with adjectives lacking a maximal degree when it quantifies over entities other than degrees. As Toledo and Sassoon (2011:145, footnote 6) note, degree modifiers can quantify over different sort of entities: “For example, completely different can be interpreted as conveying ‘different in every respect’; hence, in this example, completely operates over a domain of ‘respects’, rather than over degrees”.

See Sánchez Masiá (2013) for an analysis of scalar sensitivity of degree modifiers in Spanish. In this paper we do not use combination with muy ‘very’ as a diagnostic of an open scale structure since, in Spanish, muy is perfectly compatible with both closed scale and open scale adjectives: El vaso está muy lleno, Juan es muy alto. A different approach to the semantic role of degree modifiers is developed in Toledo and Sassoon (2011), Solt (2012) and others.

-

(i)

McNally (2011) provides examples of adjectives interpreted with absolute standards that are not scalar endpoints and also examples of adjectives which can be interpreted with non-endpoint standards despite having closed scales. Accordingly, she redefines the relative/absolute dichotomy without resorting to scalar structure and scalar boundaries: what differentiates relative and absolute standards is not the nature of the degree that marks the standard, but rather the applicability criteria for the property in question. Absolute adjectives contribute properties that are ascribed to the individual via rule. The property contributed by a relative adjective is ascribed to the individual via similarity. Absolute adjectives involve comparing a representation associated with a specific individual (for example one concerning the degree of fullness of a specific class) against a more abstract representation (for example, a degree of fullness for glasses in general). Relative adjectives require comparing a representation of a specific individual or property of that individual against another representation of an equally specific individual or one (or more) of its properties. Thus only relative adjectives are context dependent in the strict sense, but absolute degrees need not be minimal or maximal degrees in absolute scalar terms.

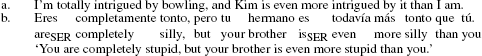

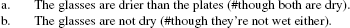

Note that the comparative form of absolute adjectives has two readings, as noted by Toledo and Sassoon (2011). In one reading, a direct comparison of the degrees of x and y with respect to the property in question is established. In the other, an indirect comparison of the degrees of x and y relative to the degrees of their respective counterparts is established. This reading arises in examples like (i):

-

(i)

In the direct comparison of degrees reading, the amount of water in the glass is smaller than the amount of water in the bottle (the outcome of the measure functions seems to be at stake here, since degrees are directly compared). In the indirect comparison reading, each individual is compared to its counterparts: in this case, the glass is fuller than the bottle, although the amount of liquid it holds is smaller. The oddity of the example comes from the interaction of these two readings.

-

(i)

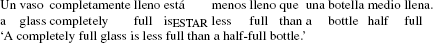

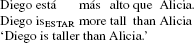

With respect to the possible readings of the comparative in these cases, consider (i):

-

(i)

In the direct comparison of degrees reading Alicia is taller than Diego (the degree of height assigned to Alicia is higher than the degree of height assigned to Diego). In the second reading, the height of Alicia relative to the counterpart determining the standard value (which is specifically a contextually salient counterpart) is smaller than the height of Diego relative to his contextually salient counterpart. Therefore, when each individual is compared to his/her counterparts, Diego is (“está”) taller than Alicia, although Alicia may be, in a direct comparison of degrees reading, taller than him.

-

(i)

These data constitute evidence that contradicts Gumiel-Molina and Pérez-Jiménez (2012). Moreover, the tight relation between scalar structure and the property of being a relative/absolute adjective assumed by these authors forces them to claim that in La niña está alta ‘The girl isESTAR tall’ the adjective is interpreted as a lower-bounded adjective with a non-context-dependent standard value, which is a minimal value on the degree scale. However, the example intuitively does not mean that the girl exceeds an absolute minimum of height in a lower-bound scale.

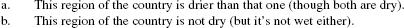

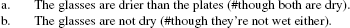

Kennedy and McNally (2005) already noted that dry behaves as a relative (in (i)) or absolute adjective (in (ii)) depending on the kind of entity it is predicated of.

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

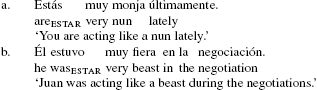

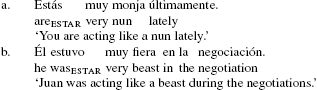

(i)

We assume that the DegreePhrase is a functional extension of the projection of the lexical category AP (which encodes the dimension expressed by the adjective). The head of the DegP expresses grammatical meaning related, in traditional terms, to the positive/comparative/superlative degree of the adjective. From the point of view of lexical insertion, the abstract functional morpheme expressing positive degree has no phonological expression in Spanish. We remain neutral with respect to the consideration of scalar structure as consubstantial to the dimension expressed by the adjective, hence part of its lexical content, or as grammatical information severed from the adjective and introduced also syntactically by a functional node.

The precision made in the text allows us to account for cases like El calor es intenso para ser invierno (lit. The heat is intense to be winter; ‘For winter, the heat is intense.’). The fact that in many cases the individual argument of the gradable adjective x is also P must be derived as an implicature (Fults 2006:176 and ff.).

Thanks to Katerine Santo for providing these examples.

Fábregas (2012) shows that some perfective adjectives like atónito ‘astonished’, perplejo ‘perplexed’ do not have equivalent verbs in contemporary Spanish, although they come from the participles of Latin verbs. This author concludes that the properties that determine the combination of perfective adjectives with estar cannot be attributed to a systematic relation with verbs.

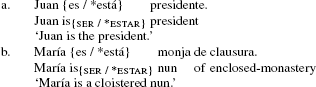

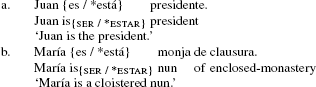

According to Roy (2013), as mentioned above, ser co-occurs with +N categories and estar co-occurs with −N categories. Therefore, the facts described in the text are related to the generalization that nouns always co-occur with ser in copular sentences:

-

(i)

Nouns can appear with estar if they are coerced into gradable entities. This is also the case with relational adjectives, as seen in the text.

-

(ii)

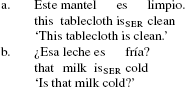

We would like also to suggest that the so-called classificative use of ser is the result of having a noun as the complement of PredP (see Roy 2013 for a parallel proposal). Therefore, in examples like (iii) (cf. (19)), the forms limpio and frío must be considered nouns, which is compatible with the kind of kind of syntactic approach taken in this paper.

-

(iii)

-

(i)

We thank Manuel Leonetti for suggesting this line of reasoning.

Note also that perfective adjectives are possible as depictive secondary predicates with stative verbs: María sabe francés borracha ‘María knows French drunk’. It seems that these adjectives, whose only possible grammatical interpretation is as absolute adjectives, force the reinterpretation of the context, giving rise to a coerced reading of the main predicate: “María only shows ‘knowing French behavior’ while drunk”.

We leave as a matter for further research the connection between comparison classes and the notion of topic, a connection already established by Klein (1980:12): “It is, I think, fairly uncontroversial that something like a comparison class does figure in the background assumptions against which sentences containing vague predicates are evaluated. Presumably, it is related to the rather amorphous idea of a ‘topic of conversation’; in many cases, the comparison class is just the set of things that the participants in a conversation happen to be talking about at a given time.”

References

Abney, Steven Paul. 1987. The English Noun Phrase in its sentential aspect. PhD diss., MIT, Cambridge, MA.

Adger, David, and Gillian Ramchand. 2003. Predication and equation. Linguistic Inquiry 34: 325–359.

Alexiadou, Artemis, Liliane Haegeman, and Melita Stavrou. 2007. Noun phrase in the generative perspective. Berlin/New York: de Gruyter.

Anderson, Curt, and Marcin Morzycki. 2015. Degrees as kinds. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory.

Arche, María Jesús. 2006. Individuals in time: tense, aspect and the individual/stage distinction. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Arche, María Jesús. 2011. Las oraciones copulativas agentivas. In 60 problemas de gramática, eds. Victoria Escandell, Manuel Leonetti, and Cristina Sánchez, 99–105. Barcelona: Akal.

Arsenijević, Boban, Gemma Boleda, Berit Gehrke, and Louise McNally. In press. Ethnic adjectives are proper adjectives. In Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS) 46.

Asher, Nicholas, and Michael Morreau. 1995. What generic sentences mean. In The generic book, eds. Gregory Carlson and Francis Jeffry Pelletier, 300–338. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Baker, Mark C. 2003. Lexical categories. Verbs, nouns and adjectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bale, Alan. 2011. Scales and comparison classes. Natural Language Semantics 19: 169–190.

Beltrama, Andrea, and Ryan Bochnak. 2015. Intensification without degrees cross-linguistically. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory.

Bhatt, Rajesh, and Roumyana Izvorsky. 1998. Genericity, implicit arguments and control. In Student Conference in Linguistics (SCIL) 7.

Bierwisch, Manfred. 1989. The semantics of gradation. In Dimensional adjectives: grammatical structure and conceptual interpretation, eds. Manfred Bierwisch and Ewald Lang, 71–237. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer.

Boleda, Gemma, Stefan Evert, Berit Gehrke, and Louise McNally. 2012. Adjectives as saturators vs. modifiers: statistical evidence. In Logic, language and meaning, eds. Maria Aloni, Vadim Kimmelman, Floris Roelofsen, Galit Sassoon, Katrin Schulz, and Matthijs Westera, 18th Amsterdam Colloquium, The Netherlands, December 19–21, 2011, 112–121. Dordrecht: Springer. Revised selected papers.

Bolinger, Dwight. 1947. Still more on ser and estar. Hispania 30: 361–366.

Borer, Hagit. 2005. Structuring sense. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bosque, Ignacio. 1990. Sobre el aspecto en los participios y los adjetivos. In Tiempo y aspecto en Español, ed. Ignacio Bosque, 177–210. Madrid: Cátedra.

Bowers, John. 1993. The syntax of predication. Linguistic Inquiry 24: 591–656.

Brownlow, Oliver. 2011. Towards a unified analysis of the syntax and semantics of get constructions. PhD diss., University of London, Queen Mary.

Brucart, Josep Maria. 2009. La alternancia ser/estar y las construcciones atributivas de localización. In Actas del V Encuentro de Gramática Generativa, ed. Alicia Avellana. 115–152. Neuquén: EDUCO.

Camacho, José. 2012. Ser and estar: the individual / stage level distinction and aspectual predication. In The handbook of Spanish linguistics, eds. José Ignacio Hualde, Antxon Olarrea, and Erin O’Rourke, 453–476. Oxford: Blackwell.

Carlson, Gregory. 1977. Reference to kinds in English. PhD diss., UMass, Amherst.

Carlson, Gregory. 2010. Generics and concepts. In Kinds, things, and stuff. Mass terms and generics, ed. Francis Jeffry Pelletier, 16–35. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1994. On evidence for partial N-movement in the Romance DP. In Paths towards universal grammar. Studies in honor of Richard S. Kayne, eds. Guiglielmo Cinque, Jan Koster, Jean-Yves Pollock, Luigi Rizzi, and Raffaella Zanuttini, 85–110. Georgetown: Georgetown University Press.

Cinque, Guiglielmo. 2010. The syntax of adjectives: a comprehensive study. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Clements, J. Clancy. 1988. The semantics and pragmatics of Spanish 〈COPULA〉+ADJECTIVE construction. Linguistics 26: 779–822.

Contreras, Heles. 1993. On null operator structures. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 11: 1–30.

Corver, Norbert. 1991. Evidence for DegP. In North East Linguistics Society (NELS) 21, 33–47. Amherst: University of Massachusetts.

Crespo, Luis. 1946. Los verbos ser y estar explicados por un nativo. Hispania 29: 45–55.

Cuervo, María Cristina. 2008. Some datives are born, some are made. In Hispanic Linguistics Symposium 12, eds. Claudia Borgonovo, Manuel Español-Echevarría, and Philippe Prévost, 26–37. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Cuervo, María Cristina. 2010. Against ditransitivity. Probus 22: 151–180.

Demonte, Violeta. 1999. A minimal account of Spanish adjective position and interpretation. In Grammatical analyses in Basque and Romance linguistics, eds. Jon Franco, Alazne Landa, and Juan Martín, 45–75. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Demonte, Violeta. 2008. Meaning-form correlations and the order of adjectives in Spanish. In Adjectives and adverbs: syntax, semantics and discourse, eds. Louise McNally and Christopher Kennedy, 71–100. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Demonte, Violeta. 2011. Adjectives. In Semantics: an international handbook of natural language meaning, eds. Claudia Maienborn, Klaus von Heusinger, and Paul Portner, 1314–1340. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Diesing, Molly. 1992. Indefinites. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Dixon, Robert M. W. 1982. Where have all the adjectives gone? Studies in Languages 1: 19–80.

Epstein, Samuel. 1984. Quantifier-pro and the LF representation of PROarb. Linguistic Inquiry 15: 499–505.

Escandell, Victoria, and Manuel Leonetti. 2002. Coercion and the stage/individual distinction. In Semantics and pragmatics of Spanish, ed. Javier Gutiérrez-Rexach, 159–180. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Fábregas, Antonio. 2007. The internal syntactic structure of relational adjectives. Probus 19: 1–36.

Fábregas, Antonio. 2012. A guide to IL and SL in Spanish: properties, problems and proposals. Borealis. An International Journal of Hispanic Linguistics 1–2: 1–71. doi:10.7557/1.1.2.2296.

Falk, Johan. 1979. Visión de norma general vs. norma individual. Ensayo de explicación de la oposición ser/estar en unión con adjetivos que denotan belleza y corpulencia. Studia Neophilologica 51: 275–293.

Fernández Leborans, María Jesús. 1999. La predicación: las oraciones copulativas. In Gramática descriptiva de la lengua Española, eds. Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte, 2357–2460. Madrid: RAE-Espasa Calpe.

Franco, Fabiola, and Donald Steinmetz. 1983. Ser y estar + adjetivo calificativo en Español. Hispania 66: 176–184.

Franco, Fabiola, and Donald Steinmetz. 1986. Taming ser and estar with predicate adjectives. Hispania 69: 379–386.

Fults, Scott. 2006. The structure of comparison: an investigation of gradable adjectives. PhD diss., University of Maryland, College Park.

Gallego, Ángel, and Juan Uriagereka. 2009. Estar = Ser + P. Paper presented at the XIX Colloquium on Generative Grammar, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Universidad del País Vasco.

Gehrke, Berit. 2015. Different ways to be passive. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory.

Gil, Irene, and Edita Gutiérrez. 2012. Características morfosintácticas de los adjetivos descriptivos. In Lingüística XL. El lingüista del siglo XXI, eds. Adrián Cabedo Nebot and Patricia Infante Ríos, 323–330. Madrid: SEL Ediciones.

Gili Gaya, Samuel. 1961. Curso superior de sintaxis española. Barcelona: Spes.

Gumiel-Molina, Silvia, and Isabel Pérez-Jiménez. 2012. Aspectual composition in “ser/estar + adjective” structures: adjectival scalarity and verbal aspect in copular constructions. Borealis. An International Journal of Hispanic Linguistics 1: 33–62. http://septentrio.uit.no/index.php/borealis/article/view/2321.

Gumiel-Molina, Silvia, Norberto Moreno-Quibén, and Isabel Pérez-Jiménez. 2013. On the aspectual properties of adjectives. Talk presented at the Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages (LSLR) 43. New York: CUNY, April 2013.

Gutiérrez-Rexach, Javier, and Enrique Mallén. 2001. NP movement and adjective position in the DP phases. In Features and interfaces in Romance, eds. Julia Herschensohn, Enrique Mallén, and Karen Zagona, 107–132. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Gutiérrez-Rexach, Javier, and Enrique Mallén. 2002. Toward a unified minimalist analysis of prenominal adjectives. In Structure, meaning and acquisition in Spanish. Papers from the 4th Hispanic Linguistic Symposium, ed. Clancy Clements, 178–192. Somerville: Cascadilla Press.

Hanssen, Federico. 1913. Gramática histórica de la lengua castellana, Paris, 1966.

Husband, Matthew. 2010. On the compositional nature of stativity. PhD diss., Michigan State University, Michigan.

Husband, Matthew. 2012. On the compositional nature of states. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Jiménez-Fernández, Ángel. 2012. What information structure tells us about individual/stage-level predicates. Borealis. An International Journal of Hispanic Linguistics 1: 1–32. http://septentrio.uit.no/index.php/borealis/article/view/2293.

Kennedy, Cristopher, and Louise McNally. 1999. From event structure to scale structure: degree modification in deverbal adjectives. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 9, eds. Tanya Matthews and Devon Strolovitch, 163–180. Ithaca: CLS Publications.

Kennedy, Cristopher, and Louise McNally. 2005. Scale structure, degree modification, and the semantics of gradable predicates. Language 81: 345–381.

Kennedy, Cristopher. 1999. Projecting the adjective: the syntax and semantics of gradability and comparison Outstanding dissertations in linguistics. New York: Garland.

Kennedy, Cristopher. 2007. Vagueness and grammar: the semantics of relative and absolute gradable adjectives. Linguistics and Philosophy 30: 1–45.

Klein, Wolfgang. 1980. Some remarks on Sanders’ typology of elliptical coordinations. Linguistics 18: 871–876.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1988/1995. Stage-level/individual-level predicates. In The generic book, eds. Gregory Carlson and Francis Jeffry Pelletier, 125–175. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Krifka, Manfred, Francis Jeffy Pelletier, Gregory N. Carlson, Alice ter Meulen, Gennaro Chierchia, and Godehard Link. 1995. Genericity: an introduction. In The generic book, eds. Gregory Carlson and Francis Jeffry Pelletier, 1–124. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Krifka, Manfred. 1989/1992. Thematic relations as links between nominal Reference and temporal constitution. In Lexical matters, eds. Ivan Sag and Ana Szabolcsi, 29–53. Chicago: CSLI Publications, Chicago University Press.

Kubota, Ai. 2015. Transforming manner adverbs into surface-subject oriented adverbs: evidence from Japanese. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory.

Landman, Meredith, and Marcin Morzycki. 2003. Event-kinds and the representation of manner. In Western Conference in Linguistics (WECOL) 11. http://www.er.uqam.ca/merlin/dg791357/material/papers/event_kinds.

Larson, Richard K., and Nagaya Takahashi. 2007. In Altaic formal linguistics II, eds. Meltem Kelepir and Balkız Öztürk. Vol. 54 of MIT working papers in linguistics, 101–120. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Lasersohn, Peter. 2005. Context dependence, disagreement and predicates of personal taste. Linguistics and Philosophy 28: 643–686.

Lewis, David K. 1983. Philosophical papers. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ludlow, Peter. 1989. Implicit comparison classes. Linguistics and Philosophy 12: 519–533.

Luján, Marta. 1981. Spanish copulas as aspect indicators. Lingua 54: 165–210.

Magri, Giorgio. 2009. A theory of individual-level predicates based on blind mandatory scalar implicatures. Natural Language Semantics 17: 245–297.

Maienborn, Claudia. 2003. Against a Davidsonian analysis of copula sentences. In North East Linguistics Society (NELS) 33, 167–186. Amherst: GLSA.

Maienborn, Claudia. 2005. A discourse-based account of Spanish ser/estar. Linguistics 43: 155–180.

Mallén, Enrique. 2001. Issues in the syntax of DP in Romance and Germanic. In Current issues in Spanish syntax and semantics, eds. Javier Gutiérrez-Rexach and Luis Silva Villar, 39–64. Berlin/New York: de Gruyter.

Marín, Rafael. 2010. Spanish adjectives within bounds. In Adjectives: formal analyses in syntax and semantics, eds. Patricia Cabredo-Hofherr and Ora Mathushansky, 307–332. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

McNally, Louise. 1994. Adjunct predicates and the individual/stage distinction. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 12, 561–576.

McNally, Louise. 1998. Stativity and theticity. In Events and grammar, ed. Susan Rothstein, 293–308. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

McNally, Louise. 2011. The relative role of property type and scale structure in explaining the behavior of gradable adjectives. In Vagueness in Communication (ViC) 2009, eds. Rick Nouwen, Robert van Rooij, Uli Sauerland, and Hans-Christian Schmitz, 151–168. Berlin: Springer.

McNally, Louise. 2012. Relative and absolute standards and degree achievements. Ms., Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

Mikkelsen, Line. 2005. Copular clauses: specification, predication and equation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pancheva, Roumyana. 2006. Phrasal and clausal comparatives in Slavic. In Annual Workshop On Formal Approaches To Slavic Linguistics. The Princeton meeting, eds. James E. Lavine, Steven Franks, Hana Filip, and Mila Tasseva-Kurktchieva, 236–257. Ann Arbor: Michigan Slavic Publications.

Park, So-Young. 2008. Functional categories: the syntax of DP and DegP. PhD diss., University of Southern California.

Percus, Orin J. 1997. Aspects of A. PhD diss., MIT, Cambridge, MA.

Pujalte, Mercedes. 2009. Condiciones sobre la introducción de argumentos: el caso de la alternancia dativa en Español. Master Thesis, Universidad Nacional del Comahue.

Pylkkänen, Liina. 2002. Introducing arguments. PhD diss., MIT, Cambridge, MA.

Pylkkänen, Liina. 2008. Introducing arguments. Cambridge: MIT press.

Roby, David. B. 2009. Aspect and the categorization of states. The case of ser and estar Spanish. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Roldán, Mercedes. 1974. Toward a semantic characterization of ser and estar. Hispania 57: 68–75.

Romero, Juan. 2009. El sujeto en las construcciones copulativas. Verba 36: 195–214.

Rothstein, Susan. 2001. Predicates and their subjects. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Rotstein, Carmen, and Yoad Winter. 2004. Total adjectives vs. partial adjectives: scale structure and higher-order modifiers. Natural Language Semantics 12: 259–288.

Roy, Isabelle. 2013. Non-verbal predication. Copular sentences at the syntax-semantics interface. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sánchez Masiá, Melania. 2013. Sobre los tipos de escala en la estructura interna de nombres y adjetivos. Talk presented at the XLII Symposium of the Sociedad Española de Lingüística, Madrid, January 2013.

Sánchez, Liliana. 1996. Word order, predication and agreement in DPs in Spanish, Southern Quechua and Southern Andean Bilingual Spanish. In Grammatical theory and Romance languages, ed. Karen Zagona, 209–218. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Sassoon, Galit, and Assaf Toledo. 2011. Absolute and relative adjectives and their comparison classes. Ms., Institute for Logic, Language and Computation, University of Amsterdam and Utrecht University.

Schmitt, Cristina, and Karen Miller. 2007. Making discourse-dependent decisions: the case of the copulas ser and estar in Spanish. Lingua 117: 1907–1929.

Schmitt, Cristina. 2005. Semi-copulas: event and aspectual composition. In Aspectual inquiries, eds. Paula Kempchinsky and Roumyana Slabakova, 121–145. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Solt, Stephanie. 2011. Notes on the comparison class. In Vagueness in Communication (ViC) 2009, revised selected papers, eds. Rick Nowen, Robert van Rooij, Uli Sauerland, and Hans-Christian Schmitz. Vol. 6571 of LNA, 189–206. Berlin: Springer.

Solt, Stephanie. 2012. Comparison to arbitrary standards. In Sinn und Bedeutung 16, eds. Ana Aguilar Guevara, Anna Chernilovskaya, and Rick Nouwen, Vol. 2, 557–570. Cambridge: MIT Working Papers in Linguistics.

Stanley, Jason. 2000. Context and logical form. Linguistics and Philosophy 23(4): 391–434.

Stowell, Tim. 1991. The alignment of arguments in adjective phrases. In Perspectives on phrase structure: heads and licensing, ed. Susan Rothstein. Vol. 25 of Syntax and semantics, 105–135. New York: Academic Press.

Syrett, Kristen. 2007. Learning about the structure of scales: adverbial modification and the acquisition of the semantics of gradable adjectives. PhD diss., Northwestern University, Evanston, IL.

Thomas, Guillaume. 2012. Temporal implicatures. PhD diss., MIT, Cambridge, MA.

Toledo, Assaf, and Galit Sassoon. 2011. Absolute vs. relative adjectives—variance within vs. between individuals. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 21, 135–154.

Wilkinson, Karina. 1991. Studies in the semantics of generic Noun Phrases. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Zagona, Karen. 2010. Ser and estar: phrase structure and aspect. In Chronos 8 Cahiers Chronos, eds. Chiyo Nishida and Cinzia Russi, 1–24. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Violeta Demonte, Olga Fernández Soriano, Manuel Leonetti, Louise McNally, Jesús Romero-Trillo and the audiences at the SEL 2012 meeting, the XX Incontro di Grammatica Generativa, the XX Colloquium on Generative Grammar, the WAASAP, the International workshop “ser and estar at the interfaces” and the members of the LyCC group, for their comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this paper. Thanks also to two anonymous reviewers and the editors of this special issue of NLLT, Elena Castroviejo and Berit Gehrke, whose comments have undoubtedly improved this article. The research underlying this work has been partly supported by a grant to the projects SPYCE II-(FFI2009-07456) and EventSynt-(FFI2009-07114) from the Spanish MICINN, and also by a grant to the project “La adquisición de los verbos copulativos ser y estar en niños de 3–6 años” (Ayudas concedidas a la Escuela de Magisterio en el marco del Convenio de Colaboración entre la Universidad de Alcalá e Ibercaja Obra Social y Cultural, 2011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gumiel-Molina, S., Moreno-Quibén, N. & Pérez-Jiménez, I. Comparison classes and the relative/absolute distinction: a degree-based compositional account of the ser/estar alternation in Spanish. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 33, 955–1001 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9284-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9284-x