Abstract

This paper investigates in detail the properties of a particular morphological reflexivization strategy in Greek, named afto-prefixation. The basic building blocks of afto-prefixation are the prefix afto-, shown to be an anti-assistive intensifier, and Middle Voice, a non-active syntactic Voice that gives rise to an existential interpretation of the implicit external argument, like the canonical Passive, but exhibits no Disjoint Reference Effects, unlike the Passive. The reflexive interpretation of afto-prefixation is the result of semantically composing these two elements. We argue that neither the prefix nor non-active morphology is a reflexivizer, i.e. neither imposes identity between two arguments of the predicate. The results of our analysis are rather surprising to the extent that they show that there exist reflexivization strategies that involve no reflexivization at all. We show that Voice and the class of intensifiers are integral elements of certain reflexivization strategies and demonstrate how and why they interact compositionally in deriving reflexive interpretations. This interaction points towards an account of both anaphoric and morphological reflexivization strategies that depends crucially on properties of predicates (rather than anaphors), and is crucially based on a dissociation of intensification from reflexivization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

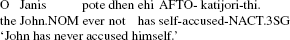

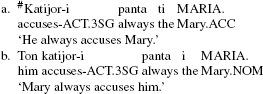

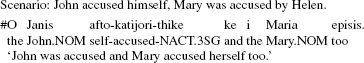

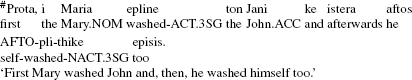

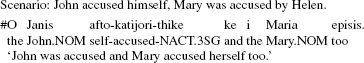

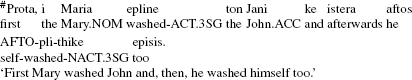

The definition is ‘broad’ since it identifies as ‘reflexive’ the meaning of sentences with non-lexical predicates, as in (i). We focus on cases of lexical predicates. We wish to thank an anonymous reviewer for discussion on an earlier definition. As the reviewer points out, if we want to identify the meaning of examples like (ii) as ‘reflexive’, theta-roles of distinct predicates with the same content (e.g. agent/cause in (ii)) should count as distinct.

-

(i)

Zelda1 said that Oscar accused her1.

-

(ii)

Zelda made herself sing.

-

(i)

For an exception see the analysis of the verbal ‘reflexivization’ marker of Kannada in Lidz (2001).

König and Siemund (2000) use the terms ‘other-directed’ vs. ‘self-directed’ verbs, for NDVs and NRVs respectively. Finally, there are ‘inherently reflexive’ verbs like English behave (oneself), which never take a referential DP as their internal argument.

See Howell (2012) for important qualifications on the claim that the identity intensifier is always focused.

Focus is syntactically expressed by F-marking, i.e. we assume that the identity intensifier is F-marked. The phonological correlate of F-marking in English is prosodic prominence. Prosodic prominence in English correlates perceptually with pitch accent, which is acoustically realized by a local maximum or minimum of the fundamental frequency. When needed, we will indicate prosodic prominence by use of capital letters.

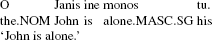

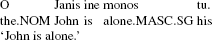

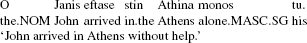

Monos tu also has a locational interpretation, as in (i). The two interpretations are clearly distinct; (22) can be true in a context in which John was never physically alone, as long as none of the people that were around assisted him in building the house. A reviewer points out that English alone in (ii) is true in the same scenario. We cannot investigate further here the possibility that alone has an anti-assistive reading.

-

(i)

-

(ii)

John built the house alone.

-

(i)

Adverbial intensifiers are ambiguous between identity and anti-assistive readings. In (25) we force the anti-assistive reading by the use of a quantificational associate. Identity intensifiers can only modify associates of type e (individual) (Ahn 2010).

See Hole (2002) for similar conclusions for German anti-assistive selbst ‘self’.

There are several issues with Tavano’s attempt to unify anti-assistive and reflexivizer herself, which fall beyond the scope of this paper. We do not attempt any such unification here.

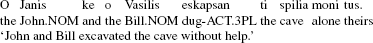

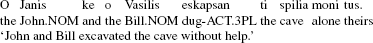

An anonymous reviewer raises the following concern for cases of anti-assistive intensifiers with plural associates, as in (ia) with the meaning in (ib). The reviewer points out that (i) can be true under a collective interpretation even if there exist sub-events of which only a part of the plurality is agent.

-

(i)

-

a.

John and Bill excavated the cave themselves.

-

b.

λe. excavated(e) & theme(the cave)(e) & agent(j+b)(e) & ∀e′∀x. (e′≤e & agent(x)(e′)) → x=j+b

-

a.

It is important to notice, however, that this is only true of contexts that assign true ‘team action’ to the plurality (Lasersohn 1995; Kratzer 2003, a.o.). True ‘team action’ is required by collectivizing adverbs like together; (iia) is felicitous in context (iib), which assigns ‘team action’, but infelicitous in the mere ‘cumulative’ context in (iic). Importantly, ‘team action’ does not require that the atoms of the relevant plurality are literal agents in every relevant sub-event; only that they are assigned joined responsibility for every sub-event (see Kratzer 2003 and the references there for extensive discussion).

-

(ii)

-

a.

John and Bill excavated the cave together.

-

b.

Context 1: John and Bill decided to excavate a cave. In several meetings, they carefully planned the excavation. John arrived at the cave, excavated its west side, and left the scene. Some time later, Bill arrived and excavated the east part.

-

c.

Context 2: John excavated the west side of the cave. Many years later and independently of John, Bill arrived at the scene and excavated the east part.

-

a.

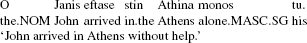

As predicted by the meaning of anti-assistive intensifiers in (34), they also require ‘team action’, like together. For example, Greek monos tu, in (iii), is felicitous in the context of (iib), but not in the context of (iic).

-

(iii)

As in much recent literature, we assume that distributive readings of examples like (iv) are derived by the use of syntactic distributivity operators (Beck and Sauerland 2000; Landman 2000, a.o.).

-

(iv)

John and Bill excavated two caves themselves.

‘John excavated two caves without help and Bill excavated two caves without help.’

-

(i)

We follow recent literature that dissociates the head Voice that introduces the external argument from the verbalizing head v (Alexiadou et al. 2006, 2014b, to appear; Harley 2013 and references therein).

As a reviewer points out, sometimes afto-prefixation is compatible with modification by monos tu. We believe that this restricted use results from using one intensifier to re-enforce the contribution of the other.

Similar considerations arise in the case of monos tu; e.g., some speakers find (i) acceptable. We also take such cases to be progressive achievements. When those speakers are asked to describe a situation that makes (i) true, they typically start describing a process: ‘John bought a ticket without anyone helping him, he got onto the train without anyone helping him, …’. We wish to thank two anonymous reviewers for asking us to clarify the status of achievement predicates modified by anti-assistive intensifiers.

-

(i)

-

(i)

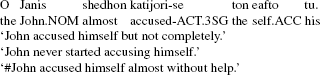

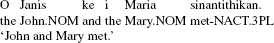

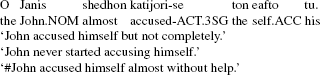

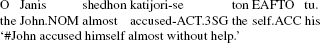

When the degree modifier modifies the verb phrase, as in (i) and (ii) with almost, the examples become grammatical and are ambiguous between two distinct readings. Crucially, however, in neither of the two readings does the degree modifier measure the level of involvement of the external argument. Notice, finally, that, unlike in the case of (49), focus on the reflexive anaphor in (iii) does not help generate the relevant reading.

-

(i)

-

(ii)

John almost accused himSELF.

‘#John accused himself almost without help.’

-

(iii)

-

(i)

We follow here roughly the discussion in van Leusen (2004). We refer to this and the works indicated in the main text for comprehensive analyses of corrective contexts and a full explication of the principles that regulate them.

This allows us to simplify the corrective contexts we are using by leaving out the Antecedent. The claim is always retrievable by the Denial; it corresponds to the content of the prejacent. We will make this simplification in the rest of this section. Other forms of corrective contexts are possible. E.g., (i) misses an explicit Denial; it is the negative particle No that flags Speaker B’s utterance as a CC. Focus works the same, with the exception that we are dealing with a case of free focus; the content of the Antecedent needs to be a member of the alternative set of the CC. Contexts like (i) give the same results for all the data discussed in this section (and also in Sects. 4.3 and 5.4, where corrective contexts are also used).

-

(i)

A: John praised Mary.

B1: No, he praised HELEN.

-

(i)

Both CCs respect the Incompatibility Condition. This is so for all the examples discussed in this section.

Albeit for different reasons than German sich. See Spathas (2010) for discussion.

Not all speakers allow the narrow focusing of prefixes like afto-, as in (62a). Notice also that since we will provide a compositional analysis of afto-prefixation, there is no problem in applying the tools of Alternative Semantics below the sentence level. See Artstein (2004) for a more general discussion of focus below the word level and the conclusion that focus below and above the word level should be treated uniformly.

The term ‘Middle’ as used here should be dissociated from its use in ‘dispositional/generic middle’ where it is used to indicate a particular construal associated with generic interpretations, as in (i). See also footnote 24.

-

(i)

This book reads easily.

-

(i)

For more discussion on the typology of Voice systems and additional differences between the Greek Middle and Passive Voice in other languages, e.g. in the distribution of by-phrases, verbal restrictions in the formation of passives etc. see Manney (2000), Kaufmann (2001), Zombolou (2004), Alexiadou and Doron (2012), Alexiadou et al. (2014b, to appear).

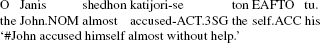

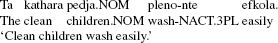

We do not discuss other cases in which NACT morphology appears, namely in the context of anticausatives, dispositional middles and deponent verbs. While Alexiadou and Doron (2012) subsume anticausatives marked with NACT under their treatment of Middle Voice, Alexiadou et al. (2014b, to appear) and Schäfer (2008) argue that they involve a semantically inert Expletive Voice, which is morphologically syncretic with Middle Voice since both of them lack a specifier (Embick 2004). Arguably deponent verbs could be analyzed as involing Expletive Voice. For a further discussion of deponent verbs in Greek, see also Zombolou (2004), Zombolou and Alexiadou (2013), Alexiadou (2013). Dispositional middles, which have been argued to exhibit Passive Voice (Tsimpli 1989; Lekakou 2005), should be re-analyzed in terms of Middle Voice. As far as we can see, this should be possible. The generic quantification over events involved in dispositional middles does not exclude reflexive events; according to (i), clean children wash easily in both reflexive and non-reflexive events.

-

(i)

-

(i)

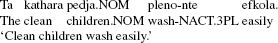

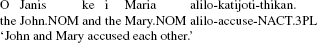

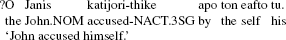

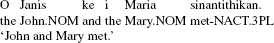

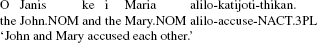

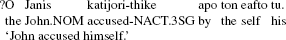

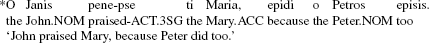

Reciprocal interpretations can be derived by use of two strategies. A morphological strategy that uses NACT, as in (i), is used with symmetric predicates like meet, kiss, etc. Non-symmetric predicates require the presence of the prefix alilo-, as in (ii). This pattern is reminiscent of the difference between NRVs and NDVs discussed in detail in Sect. 6. We have to leave for future research the extent to which alilo-prefixation can be subsumed under the present analysis, see Alexiadou (2014) for some further discussion.

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(i)

We wish to thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing out the necessity of treating the restriction as a presupposition.

Our treatment of Middle Voice predicts that intransitive NRVs with NACT are unaccusatives. The status of such predicates with regard to unaccusativity is contended in the literature. Whereas Embick (1998, 2004) treats them as unaccusatives, Papangeli (2004), Tsimpli (1989, 2006) treat them as unergatives. The number of available unaccusativity diagnostics in Greek is limited (cf. Markantonatou 1992; Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou 1999) and most of the diagnostics that have been proposed have been criticized. Alexiadou (2014) and Alexiadou and Schäfer (2014) argue that, although most tests do not provide direct evidence for an unaccusative treatment of intransitive NRVs they are compatible with such an analysis; what most diagnostics seem to show is that intransitive NRVs are, in fact, not unergatives. In particular, the observation that intransitive NRVs in Greek can express a reflexive change of state suggests that an internal argument must be projected in the syntax.

Notice that no phrase in (74) denotes a relation from individuals to properties of events (with the possible exception of the root, see fn. 48), so that no attachment site for anti-assistive intensifiers appears to be available. We will solve this type-mismatch in Sect. 5, where we argue that movement of the theme DP to a projection of Voice creates a derived predicate that anti-assistive intensifiers attach to.

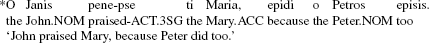

The presence of the by-phrase in (76a) and plural third person agreement on the embedded verb in (76b), force the NRV to be understood disjointly in those cases. This is not the case in (76c), where, as usual, the encyclopedic information associated with the verbal event favors (but does not force) (76c) to be understood as a description of a reflexive event. We come to this in detail right below.

A possible way to treat examples like (90) in a lexical approach is to generalize the presupposition of Pass, as in (i), where Θ is the set of thematic relations. The presupposition in (i) requires that all theta roles of the relevant event are fulfilled by distinct individuals. As a reviewer points out, both the entries in (72) and (i) use the theme role as a semantic primitive, contra Kratzer (2003), who argues on the basis of cumulativity that only the agent theta role is a semantic primitive. See Williams (2009) for arguments against distinguishing the agent and theme roles in this manner.

-

(i)

Presupposition of Pass: ∀fes,t,f′es,t ∈ Θ. ∀x, y. f(x)(e) & f′(y)(e) → x≠y

-

(i)

German and Icelandic do allow passives of naturally reflexive verbs. See Schäfer (2012) for discussion and an account.

As a reviewer points out, similar problems arise with examples like (i), which can be used to describe reflexive events.

-

(i)

John wasn’t killed by anyone but himself.

-

(i)

An account in terms of a null indefinite would also have to stipulate that the indefinite cannot undergo Quantifier Raising.

In Greek the status of reflexive anaphors in by-phrases, as in (i), is not clear; some speakers find (i) acceptable, while others do not. As in English, focus seems to improve (i). The Greek facts are, at this point, not very informative, however, as Greek by-phrases are in general more restricted than their English counterparts, a fact that has been attributed to Middle Voice (see e.g. Manney 2000).

-

(i)

-

(i)

If the proper account of DRE turns out to be binding theoretical the difference between Passive and Middle could be described in terms of syntactically projecting an implicit argument (Passive) or not syntactically projecting an implicit argument (Middle). An analysis of non-active Voices along these lines is developed—for different reasons—in Doron (2003) and Alexiadou and Doron (2012).

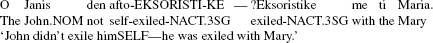

The data presented in this section argue against any designated operations of passivization and reflexivization in Greek, regardless of whether they are syntactic, as suggested in the main text, or lexical (e.g., in the form of lexical rules that alter the argument structure of predicates).

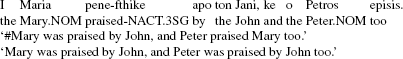

Merchant (2013) argues that the licensing of Active-Passive Mismatches in ellipsis is sensitive to the size of the elided material. In his own words, “Eliding a node that contains Voice […] will rule out voice mismatches, while eliding a node to which Voice is external […] will allow voice mismatches” (Merchant 2013:89). He shows that VP-ellipsis in English licenses voice mismatches and that sluicing, gapping, stripping/bare argument ellipsis, and fragment answers, which target constituents that include Voice, do not. The ungrammaticality of (100)/(101), then, can be taken to show that reflexivization by herself in English is not a Voice alternation (contra Ahn 2012). The ellipsis in the Greek examples in (98) and (99) is not a case of VP-ellipsis, as manifested, e.g., by the fact that, unlike VP-ellipsis, it is not licensed in subordinate clauses, as in (i), but rather a case of stripping/bare argument ellipsis. As expected, ellipsis in Greek does not license voice mismatches of the active-passive type, as shown in (ii).

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(i)

Zwicky and Sadock (1975) also use the contradiction test. Ambiguous terms do not give rise to semantic incompatibilities that formally look like contradictions. So, (ii) is not a contradiction, because of the two different meanings of bank. All attempts to apply the test for the data investigated here have yielded some version or other of the correction test.

-

(i)

That bank isn’t a bank.

-

(i)

(108) is judged slightly better than (107). This is so because correction can sometimes target the enriched meanings of the claims (see Asher 1995; van Leusen 2004; Asher and Lascarides 2003 for the role of implicatures in licensing corrective contexts). In the case of (108), the ‘enriched’ meaning would be the implication that the claim is used to describe a reflexive situation.

The argument goes through in exactly the same way if we assume that pitch accent on the verb plithike indicates focus on the putative Reflexive Voice head. In this case the alternative set contains propositions after replacing Reflexive Voice with other Voice heads, i.e. Middle. The content of CC in, e.g., (108), is a member of this set since the proposition that Mary washed John entails that someone washed John (the result of replacing Reflexive with Middle/Passive in generating the alternative set).

We assume here that pitch accent on being indicates that the Passive head is focused. As before, nothing hinges on focus here.

The example is infelicitous irrespective of focus placement. We indicate VP-level focus here.

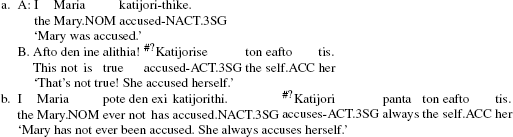

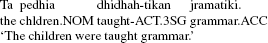

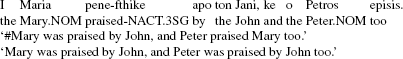

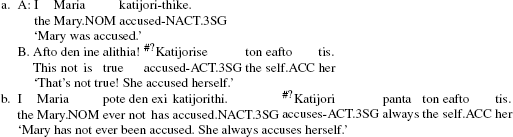

A reviewer raises the concern that some of the Corrective Contexts above involve meta-linguistic negation. Meta-linguistic negation in similar contexts has been evoked in the literature on anti-causatives. It has been argued there that meta-linguistic negation can license a corrective context that is infelicitous if logical negation is involved (Horvath and Siloni 2011, 2013; Schäfer and Vivanco 2013; pace Koontz-Garboden 2009; Beavers and Koontz Garboden 2013a, 2013b). Meta-linguistic negation does not affect the examples reported here. The judgments remain identical if (a) we use a Corrective Context that directly targets the truth-conditional content of the rejected Claim, or (b) as the reviewer suggests, we use a Negative Polarity Item that excludes an interpretation of negation as meta-linguistic (pote ‘ever’ in (iib)). We exemplify here with examples (113) (in (i)) and (114) (in (ii)). The same holds for all the Corrective Contexts used in this paper. See also footnote 55.

-

(i)

-

a.

A: Mary was being accused.

B: That’s not true! She was accusing herSELF.

-

b.

Mary has not ever been accused. She always accuses herSELF.

-

a.

-

(ii)

-

(i)

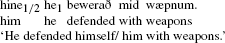

Hole (2002) argues that the English adverbial intensifier and German adverbial selbst attach to Voice. His argument is based on the behaviour of gerunds. Only those gerunds that license direct accusative-marked objects (and, thus, have been argued to include Voice, as in Kratzer 1996) can license modification by the anti-assistive intensifier (cf. (ia–c)).

-

(i)

-

a.

I remember his rebuilding of the barn (*himself).

-

b.

I remember his rebuilding the barn (himself).

-

c.

I remember him rebuilding the barn (himself).

-

a.

-

(i)

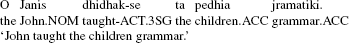

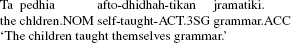

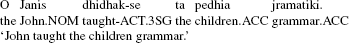

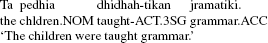

As an anonymous reviewer correctly points out, goal arguments in the double accusative construction (Anagnostopoulou 2003a, 2003b), as in (i), can be passivized, as in (ii). As predicted by our account, (ii) is only true of non-reflexive events, and licenses afto-prefixation, as in (iii).

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(iii)

-

(i)

The only possible candidate is the root √katijor. The issue whether roots partake in compositional interpretation is currently intensely debated (Arad 2005; Marantz 2007; Embick 2010; Borer 2013; Anagnostopoulou and Samioti 2014). The data from association with focus indicate that the combination of afto- and the predicate is fully compositional. Moreover, most decompositional approaches do not assume that roots introduce event arguments, as would be required for afto-prefixation to take place (but see Levinson 2014; Rossdeutscher 2014 for exceptions). In any case, the arguments in Sects. 3.2 and 5.1 in favor of classifying afto- as a Voice Adjunct prohibit an analysis in terms of affixation to the root.

Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou (1998) have argued that in Greek type languages DPs never move to Spec,TP; they either remain within the Voice/vP domain, or they are base generated as topics in a clitic-left dislocated position. In English, however, in the absence of an expletive, DPs necessarily vacate the Voice/vP domain.

As a reviewer correctly points out, the same mechanism (covert A-movement that creates a derived predicate) is used in Pylkkänen (2008) to derive the fact that derived subjects are available for depictive modification.

The situation in this case is exactly as in the analysis of Parasitic Gaps in Nissenbaum (2000), where Parasitic Gaps can only be attached counter-cyclically after movement has created a derived predicate.

In an appropriate context (129) is felicitous under an additive reading of herself.

As with previous cases, the judgments here cannot be attributed to meta-linguistic negation. This can be manifested, for example, by use of Negative Polarity Items, as in (i).

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(i)

Our analysis of (151)/(152) predicts that (152b) will be improved as a CC in the same context in the case of VP-level focus. This seems to be the case, as shown in (i), even if the contrast is admittedly subtle.

-

(i)

-

(i)

Unless in contexts that require narrow focusing of the reflexive anaphor. See the discussion around example (161)/(162).

In English, only NRVs allow intransitive construals with reflexive interpretations. Bergeton (2004), Bergeton and Pancheva (2012) argue that an example like John washed is reflexivized by a null anaphor, equivalent to SE-anaphors in other Germanic languages. See Alexiadou et al. (2014a) for arguments against this analysis and an alternative. We put aside English in this section.

According to Reinhart and Reuland (1993), a predicate is reflexive iff two of its co-arguments are co-indexed.

In different lexicalist implementations, as in, e.g., the Theta System of Reinhart and Siloni (2005), the predicate is reflexive-marked after application of a lexical Reflexivization Operation that turns the transitive entry into an intransitive one.

Bergeton (2004), Bergeton and Pancheva (2012) argue that all complex anaphors in Germanic languages should be decomposed this way. We do not agree that this is necessarily the case; whatever the origin of the SELF-element, it is possible that complex anaphors have been re-analyzed. In Sect. 3.2.4 we adopted an analysis of English anaphoric herself as an arity reducer. See Spathas (2012, 2013) for more discussion on how to tease apart reflexivizers and intensifiers.

Several issues arise in this approach that we cannot address here. For one thing, SELF-anaphors do not give rise to centrality effects (see Geurts 2004 and Sæbø 2009 for attempts of an explanation) which are usually connected to identity intensifiers (Eckardt 2001). Also, SELF-anaphors do not have to be prosodically prominent. Most importantly, it is not clear that the alternatives introduced by the SELF-anaphors have the same status as the alternatives introduced by regular F-marking. For example, a focus-associating operator never associates with a SELF-anaphor, unless the anaphor is prosodically prominent (i.e. regularly F-marked). These issues do not arise in the case of afto- discussed in the next section and we leave them aside. Howell (2012) shows that even regular identity intensifiers are not always prosodically prominent. He develops an account that retains Eckardt’s identity semantics, but treats identity intensifiers themselves as focus associating operators. We leave it for future research to investigate whether the idea presented in the main text can be reformulated using Howell’s (2012) analysis in a way that deals with the problems mentioned here.

There are technical issues, as well. For example, Reinhart and Reuland’s (1993) definition of reflexive predicates as predicates with co-indexed arguments cannot be used straightforwardly for the relevant Greek examples. The definition is problematic more generally if co-indexation is abandoned as a syntactic relation. See Reuland (2001, 2011) for extensive discussion of these issues within Reflexivity Theory.

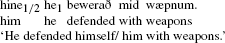

Bergeton (2004) and Bergeton and Pancheva (2012) use the same reasoning to explain the emergence of specialized reflexive anaphors in English. Old English (OE) used personal pronouns for reflexive readings, as in (i) (Siemund 2000:2.44). The OE intensifier sylf ‘self’, then, was first used with NDVs in order to mark the failure of the expectations generated by the lexical content of those predicates. Notice that the pattern in OE is closer to Greek than in, e.g., Dutch, since OE (i) does not receive an unambiguously reflexive interpretation. This raises the possibility, that sylf was not an adnominal identity intensifier, as suggested by Bergeton (2004) and Bergeton and Pancheva (2012), but rather an anti-assistive intensifier, since only the addition of an anti-assistive intensifier could disambiguate examples like (i) in favor of a reflexive interpretation. We cannot investigate this issue any further here.

-

(i)

-

(i)

Adding afto-, as in (i), does not improve the example, however. In this case, parallelism forces the presence of afto- in the elided material too, rendering the second clause false in the given context.

-

(i)

-

(i)

Unlike the Norwegian SELF-anaphor in (161) above, afto-prefixation is out with NRVs even in the presence of a contextually prominent alternative, as in (ii). The free adverbial intensifier monos tu, as in (156), is felicitous in this context. This is the only case we have identified in which the parallelism between afto- and free anti-assistive intensifiers breaks down. It involves a single class of cases, NRVs. Recall from Sects. 3.2.4 and 5.4 that afto- is licensed in similar contexts in the case of NDVs, indicating that contrastive contexts are not a problem for treating afto- as an anti-assistive intensifier. We have to leave an account of (i) for future research.

-

(i)

-

(i)

References

Adger, David, and George Tsoulas. 2000. Aspect and lower VP adverbials. In Adverbs and adjunction, eds. Artemis Alexiadou and Peter Svenonius, 1–19. Potsdam: Linguistics in Potsdam.

Ahn, Byron. 2010. More than just emphatic reflexives themselves: Their syntax, semantics and prosody. Master’s Thesis. UCLA.

Ahn, Byron. 2012. External argument focus and reflexive syntax. Coyote Papers 20.

Alexiadou, Artemis. 1997. Adverb placement: A case study in antisymmetric syntax. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Alexiadou, Artemis. 2013. Where is non-active morphology? In Proceedings of the 20th conference on Head-driven phrase structure grammar. CSLI publications, 244–262.

Alexiadou, Artemis. 2014. Roots in transitivity alternations: afto/auto reflexives. In The syntax of roots and the roots of syntax, eds. Artemis Alexiadou, Hagit Borer, and Florian Schäfer. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Alexiadou, Artemis, and Elena Anagnostopoulou. 1998. Parametrizing Agr: Word order, verb-movement and EPP-checking. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 16(3): 491–539.

Alexiadou, Artemis, and Elena Anagnostopoulou. 1999. Tests for unaccusativity in a language without tests for unaccusativity. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Greek Linguistics, 23–31.

Alexiadou, Artemis, and Edit Doron. 2012. The syntactic construction of two non-active Voices: Passive and middle. Journal of Linguistics 48: 1–34.

Alexiadou, Artemis, and Florian Schäfer. 2014. Towards a non-uniform analysis of naturally reflexive verbs. In Proceedings of WCCFL 31, ed. R. E. Santana-LaBarge, 1–10.

Alexiadou, Artemis, Elena Anagnostopoulou, and Florian Schäfer. 2006. The properties of anticausatives crosslinguistically. In Phases of interpretation, ed. Mara Frascarelli, 187–211. Berlin: Mouton.

Alexiadou, Artemis, Florian Schäfer, and Giorgos Spathas. 2014a. Delimiting Voice in Germanic: On object-drop and naturally reflexive verbs. In Proceedings of NELS 44, eds. Leland Kusmer and Jyoti Iyer.

Alexiadou, Artemis, Elena Anagnostopoulou, and Florian Schäfer. 2014b, to appear. External arguments in transitivity alternations: A layering approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2003a. The syntax of ditransitives: Evidence from clitics. Berlin, New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2003b. Participles and Voice. In Perfect explorations, eds. Artemis Alexiadou, Monika Rathert, and Arnim von Stechow, 1–36. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena, and Martin Everaert. 1999. Towards a more complete typology of anaphoric expressions. Linguistic Inquiry 30(1): 97–118.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena, and Panagiota Samioti. 2014. Domains within words and their meanings: A case study. In The syntax of roots and the roots of syntax, eds. Artemis Alexiadou, Hagit Borer, and Florian Schäfer. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Arad, Maya. 2005. Roots and patterns: Hebrew morpho-syntax. Dordrecht: Springer.

Arquiola, Elena Felíu. 2003. Morphology, argument structure and lexical semantics: The case of Spanish auto- and co- prefixation to verbal bases. Linguistics 41(3): 495–513.

Artstein, Ron. 2004. Focus below the word level. Natural Language Semantics 12(1): 1–22.

Asher, Nicholas. 1995. From discourse macro-structure to micro-structure and back again: Discourse semantics and the focus/background distinction. In Proceedings of the Conference on Semantics in Context, eds. Hans Kamp and Barbara Partee. SFB340 Report, University of Stuttgart.

Asher, Nicholas, and Alex Lascarides. 2003. Logics of conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bach, Emmon. 1980. In defense of passive. Linguistics and Philosophy 3: 297–34l.

Baker, Mark. 1988. Incorporation: A theory of grammatical function changing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Baker, Mark, Kyle Johnson, and Ian Roberts. 1989. Passive arguments raised. Linguistic Inquiry 20: 219–252.

Beaver, David, and Brady Clark. 2008. Sense and sensitivity. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Beavers, John, and Andrew Koontz Garboden. 2013a. In defense of the reflexivization analysis of anticausativization. Lingua 131: 199–216.

Beavers, John, and Andrew Koontz Garboden. 2013b. Complications in diagnosing lexical meaning: A rejoinder to Horvath and Siloni (2013). Lingua 134: 210–218.

Beck, Sigrid, and Uli Sauerland. 2000. Cumulation is needed: A reply to Winter (2000). Natural Language Semantics 8(4): 349–371.

Bergeton, Uffe. 2004. The independence of binding and intensification. PhD thesis, University of Southern California.

Bergeton, Uffe, and Roumyana Pancheva. 2012. A new perspective on the historical development of English intensifiers and reflexives. In Grammatical change: Origins, nature, outcomes, eds. Dianne Jonas, John Whitman, and Andrew Garrett, 123–138. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bhatt, Rajesh, and Roumyana Pancheva. 2006. Implicit arguments. In The Blackwell companion to syntax, Vol. II, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk, 554–584. Oxford: Blackwell.

Borer, Hagit. 2013. Taking form. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bresnan, Joan. 1978. A realistic transformational grammar. In Linguistic theory and psychological reality, eds. Morris Halle, Joan Bresnan, and George A. Miller, 1–59. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bruening, Benjamin. 2012. By-phrases in passives and nominals. Syntax 16: 1–41.

Bruening, Benjamin. 2014. Word formation is syntactic: Adjectival passives in English. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 32: 363–422.

Büring, Daniel. 2005. Binding theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Castella, Marta. 2010. The semantics and syntax of auto. MA Thesis, Utrecht University.

Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures on government and binding. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and functional heads: A cross-linguistic perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dechaine, Rose-Marie, and Martina Wiltschko. 2012. The heterogenity of reflexives. Ms. UBC.

Doron, Edit. 2003. Agency and voice: The semantics of the Semitic templates. Natural Language Semantics 11: 1–67.

Doron, Edit, and Malka Rappaport Hovav. 2009. A unified approach to reflexivization in Semitic and Romance. Brill’s Annual of Afroasiatic Languages and Linguistics 1: 75–105.

Eckardt, Regine. 2001. Re-analysing selbst. Natural Language Semantics 9: 371–412.

Embick, David. 1998. Voice systems and the syntax/morphology interface. In Papers from the UPenn/MIT roundtable on argument structure and aspect, ed. Heidi Harley. Vol. 32 of MIT Working Papers in Linguistics, 41–72. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Embick, David. 2004. Unaccusative syntax and verbal alternations. In The unaccusativity puzzle: Explorations of the syntax-lexicon interface, eds. Artemis Alexiadou, Elena Anagnostopoulou, and Martin Everaert, 137–158. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Embick, David. 2010. Localism vs. globalism in morphology and phonology. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Everaert, Martin. 1986. The syntax of reflexivization. Dordrecht: Foris.

Faltz, Leonard M. 1985[1977]. Reflexivization: A study in universal syntax. New York: Garland.

Fodor, Jerry, and Janet Dean Fodor. 1980. Functional structure, quantifiers, and meaning postulates. Linguistic Inquiry 11: 759–769.

Gast, Volker, and Peter Siemund. 2006. Rethinking the relationship between SELF-intensifiers and reflexives. Linguistics 44(2): 343–381.

Gehrke, Berit, Artemis Alexiadou, and Florian Schäfer. 2014. The argument structure of adjectival participles revisited. Lingua 149B: 95–214.

Geurts, Bart. 2004. Weak and strong reflexives in Dutch. In Proceedings of the ESSLLI workshop on semantic approaches to binding theory, eds. Philippe Schlenker and Ed Keenan.

Harley, Heidi. 2013. External arguments and the Mirror Principle: On the distinction of Voice and v. Lingua 125: 34–57.

Haspelmath, Martin. 2008. A frequentist explanation of some universals of reflexive marking. Linguistic Discovery 6(1): 40–63.

Heim, Irene. 1998 [1993]. Anaphora and semantic interpretation: A reinterpretation of Reinhart’s approach. In The interpretive tract, eds. Uli Sauerland and Orin Percus, 205–246. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Heim, Irene, and Angelika Kratzer. 1998. Semantics in generative grammar. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hellan, Lars. 1988. Anaphora in Norwegian and the theory of grammar. Dordrecht: Foris.

Hole, Daniel. 2002. Agentive selbst in German. In Sinn und Bedeutung 6: Proceedings of the sixth Meeting of the Gesellschaft für Semantik, eds. Graham Katz, Sabine Reinhard, and Philip Reuter. Publications of the Institute of Cognitive Science. Osnabrück: University of Osnabrück.

Horvath, Julia, and Tal Siloni. 2011. Anticausatives: Against reflexivization. Lingua 121: 2176–2186.

Horvath, Julia, and Tal Siloni. 2013. Anticausatives have no cause(r): A rejoinder to Beavers and Koontz-Garboden. Lingua 131: 217–230.

Howell, Jonathan. 2012. Meaning and prosody. PhD dissertation, Cornell University.

Iatridou, Sabine. 1988. Clitics, anaphors, and a problem of co-indexation. Linguistic Inquiry 19: 698–703.

Kaufmann, Ingrid. 2001. Medium und Reflexiv: eine Studie zur Verbsemantik. Habilitationsschrift, University of Düsseldorf.

Keenan, Edward. 1980. Passive is phrasal (not sentential or lexical). In Lexical grammar, eds. Teun Hockstra, Harry van der Hulst, and Michael Moortgat, 181–213. Dordrecht: Foris.

Kemmer, Suzanne. 1993. The middle voice. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Kiparsky, Paul. 2013. Towards a null theory of the passive. Lingua 125: 7–33.

Klaiman, M. H. 1991. Grammatical voice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

König, Ekkehard, and Volker Gast. 2006. Focused expressions of identity—a typology of intensifiers. Linguistic Typology 10(2): 223–276.

König, Ekkehard, and Peter Siemund. 2000. Locally free self-forms, logophoricity and intensification in English. English Language and Linguistics 4: 183–204.

Koontz-Garboden, Andrew. 2009. Anticausativization. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 27: 77–138.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1996. Severing the external argument from its verb. In Phrase structure and the lexicon, eds. Johan Rooryck and Laurie Zaring, 109–137. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Kratzer, Angelika. 2000. Building statives. In Proceedings of the twenty-sixth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, eds. Lisa J. Conathan, Jeff Good, Darya Kavitskaya, Alyssa B. Wulf, and Alan C. L. Yu. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley Linguistics Society.

Kratzer, Angelika. 2003. The event argument, chapter 3. Ms. University of Massachusetts. Available at http://www.semanticsarchive.net.

Labelle, Marie. 2008. The French reflexive and reciprocal se. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 26: 833–876.

Landau, Idan. 2010. The explicit syntax of implicit arguments. Linguistic Inquiry 41: 357–388.

Landman, Fred. 2000. Events and plurality. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Lasersohn, Peter. 1993. Lexical distributivity and implicit arguments. In Proceedings from Semantics and Linguistic Theory III, eds. Utpal Lahiri and Adam Wyner, 145–161. Ithaca: CLC Publications.

Lasersohn, Peter. 1995. Plurality, conjunction and events. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Lebeaux, David. 1988. Language acquisition and the form of the grammar. PhD dissertation, University of Massachussetts.

Lechner, Winfried. 2012. Towards a theory of transparent reflexivization. Ms., University of Athens.

Lekakou, Marika. 2005. In the middle, somewhat elevated. The semantics of middles and its crosslinguistic realization. PhD thesis, University of London.

Levinson, Lisa. 2014. The ontology of roots and verbs. In The syntax of roots and the roots of syntax, eds. Artemis Alexiadou, Hagit Borer, and Florian Schäfer. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lidz, Jeffrey. 2001. The argument structure of verbal reflexives. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 19(2): 311–353.

Manney, Linda. 2000. Middle Voice in Modern Greek: Meaning and function of an inflectional category. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Marantz, Alec. 1997. No escape from syntax: Don’t try morphological analysis in the privacy of your own lexicon. In Proceedings of the 21st Annual Penn Linguistics Colloquium, eds. Alexis Dimitriadis, Laura Siegel, Clarissa Surek-Clark, and Alexander Williams. Vol. 4.2 of Penn Working Papers in Linguistics, 201–225.

Marantz, Alec. 2007. Phases and words. In Phases in the theory of grammar, ed. Sook-Hee Choe. Seoul: Dong In Publisher.

Marelj, Marijana, and Eric Reuland. 2012. Deriving reflexives: Deriving the lexicon-syntax parameter. Ms., UiL-OTS, Utrecht.

Markantonatou, Stella. 1992. The Syntax of modern Greek Noun Phrases with a derived nominal head. PhD Dissertation, University of Essex.

Martí, Luisa. 2006. Unarticulated constituents revisited. Linguistics and Philosophy 29(2): 135–166.

McIntyre, Andrew. 2013. Adjectival passives and adjectival participles in English. In Non-canonical passives, eds. Artemis Alexiadou and Florian Schaefer. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Merchant, Jason. 2013. Voice and ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 44(1): 77–108.

Mittwoch, Anita. 1982. On the difference between eating and eating something: Activities versus accomplishments. Linguistic Inguiry 13(1): 113–122.

Nissenbaum, Jon. 2000. Covert movement and parasitic gaps. In Proceedings of NELS 30, eds. M. Hirotani, A. Coetzee, N. Hall, and J.-Y. Kim, 541–555. Amherst: GLSA Publications.

Papangeli, Dimitra. 2004. The morpho-syntax of argument realization: Greek argument structure and the Lexicon-Syntax interface. PhD dissertation, University of Utrecht. LOT dissertation series.

Partee, Barbara, and Emmon Bach. 1981. Quantification, pronouns, and VP anaphora. In Formal methods in the study of language: Proceedings of the Third Amsterdam Colloquium, eds. Jeroen Groenendijk, Theo Janssen, and Martin Stokhof, 445–48l.

Patel-Grosz, Prity. 2013. Complex reflexives and the principle A problem. Journal of South Asian Languages 6: 25–50.

Pylkkänen, Liina. 2008. Introducing arguments. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Reinhart, Tanya, and Eric Reuland. 1993. Reflexivity. Linguistic Inquiry 24: 657–720.

Reinhart, Tanya, and Tali Siloni. 2005. The lexicon-syntax parameter: Reflexivization and other arity operations. Linguistic Inquiry 36(3): 389–436.

Reuland, Eric. 2001. Primitives of binding. Linguistic Inquiry 32: 439–492.

Reuland, Eric. 2011. Anaphora and language design. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rivero, Maria Luisa. 1992. Adverb incorporation and the syntax of adverbs in Modern Greek. Linguistics and Philosophy 15: 289–331.

Rooth, Mats. 1985. Association with focus. PhD dissertation, University of Massachusetts.

Rossdeutscher, Antje. 2014. When roots license and when they respect semantico-syntactic structure in verbs. In The syntax of roots and the roots of syntax, eds. Artemis Alexiadou, Hagit Borer, and Florian Schäfer. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rothstein, Susan. 2004. Structuring events: A study in the semantics of Aspect. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Sæbø, Kjell. 2009. Self intensification and focus interpretation. In Structuring information in discourse: The explicit/implicit dimension, eds. Bergljot Behrens and Cathrine Fabricius-Hansen. Vol. 1 of Oslo studies in language, 109–129.

Schäfer, Florian. 2008. The syntax of (anti-)causatives. External arguments in change-of-state contexts. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Schäfer, Florian. 2012. The passive of reflexive verbs and its implications for theories of binding and case. Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics 15(3): 213–268.

Schäfer, Florian, and Margot Vivanco. 2013. Reflexively marked anticausatives are not semantically reflexive. Talk at Going Romance, Univerity of Amsrerdam.

Sennet, Adam. 2011. Ambiguity. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2011 Edition), ed. Edward N. Zalta. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2011/entries/ambiguity/.

Siemund, Peter. 2000. Intensifiers: A comparision of English and German. London: Routledge.

Spathas, Giorgos. 2010. Focus on anaphora. PhD dissertation, University of Utrecht. LOT dissertation series.

Spathas, Giorgos. 2011. Focus on reflexive anaphors. In Proceedings of the Semantics and Linguistic Theory XX, eds. David Lutz and Nan Li, 471–488. Cornell: CLC Publications.

Spathas, Giorgos. 2012. Reflexivizers and intensifiers: Consequences for a theory of focus. In Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 17, eds. Emmanuel Chemla, Vincent Homer, and Grégoire Winterstein, 581–598.

Spathas, Giorgos. 2013. Reflexive anaphors and association with focus. In Proceedings of SALT 23, ed. Todd Snider, 376–393. Cornell University, Ithaca: CLC Publications.

Szabolcsi, Anna. 1992. Combinatory grammar and projection from the lexicon. In Lexical matters, eds. Ivan Sag and Anna Szabolcsi. Stanford: Stanford University.

Tavano, Erin. 2006. A bound-variable analysis of the adverbal emphatic reflexive, or How I wrote this paper myself. Master’s Thesis, University of Southern California.

Theophanopoulou-Kontou, Dimitra. 1981. Middle reflexive verbs in Modern Greek. Studies in Greek Linguistics 2: 51–78.

Tsimpli, Ianthi Maria. 1989. On the properties of the passive affix in Modern Greek. UCL Working Papers in Linguistics 1: 235–260.

Tsimpli, Ianthi Maria. 2006. The acquisition of voice and transitivity alternations in Greek as native and second language. In Paths of development in L1 and L2 acquisition: In honor of Bonnie D. Schwartz, eds. Sharon Unsworth, Teresa Parodi, Antonella Sorace, and Martha Young-Scholten, 15–55. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

van Leusen, Noor. 2004. Incompatibility in context: A diagnosis of correction. Journal of Semantics 21(4): 415–441.

Williams, Edwin. 1985. PRO and subject of NP. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 3: 297–315.

Williams, Edwin. 1987. Implicit arguments, the binding theory, and control. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 5(2): 151–180.

Williams, Alexander. 2009. Themes, cumulativity, and resultatives: Comments on Kratzer 2003. Linguistic Inquiry 40(4): 686–700.

Zombolou, Katerina. 2004. Verbal alternations in Greek: A semantic approach. PhD thesis, University of Reading.

Zombolou, Katerina, and Artemis Alexiadou. 2013. The canonical function of deponent verbs in Modern Greek. In Morphology and meaning, eds. F. Rainer et al., 331–344. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Zwicky, Arnold, and Jerrold Sadock. 1975. Ambiguity tests and how to fail them. Syntax and Semanticsa 4: 1–36.

Acknowledgements

We thank Elena Anagnostopoulou, Winnie Lechner, Jakub Dotlačil, Martin Haspelmath, Gereon Müller, as well as three anonymous reviewers for Natural Language and Linguistic Theory for insightful comments and suggestions. This work was supported by a DFG grant to the project B6 ‘Underspecification in Voice systems and the syntax-morphology interface’, as part of the Collaborative Research Center 732 Incremental Specification in Context at the University of Stuttgart.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Spathas, G., Alexiadou, A. & Schäfer, F. Middle Voice and reflexive interpretations: afto-prefixation in Greek. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 33, 1293–1350 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-014-9279-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-014-9279-z